The Clockwork Man (14)

By:

June 19, 2013

HILOBROW is pleased to present the fourteenth installment of our serialization of E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man. New installments will appear each Wednesday for 20 weeks.

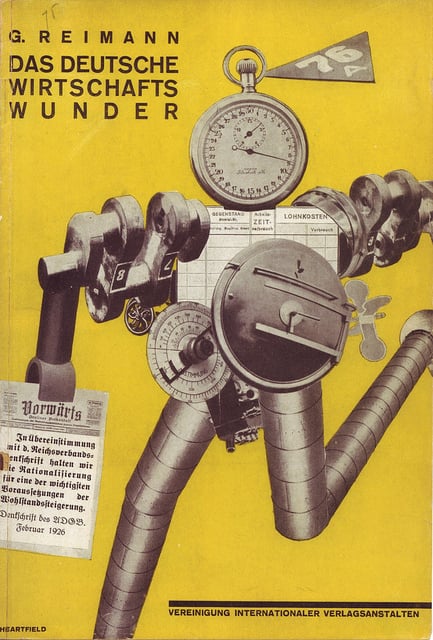

Several thousand years from now, advanced humanoids known as the Makers will implant clockwork devices into our heads. At the cost of a certain amount of agency, these devices will permit us to move unhindered through time and space, and to live complacent, well-regulated lives. However, when one of these devices goes awry, a “clockwork man” appears accidentally in the 1920s, at a cricket match in a small English village. Comical yet mind-blowing hijinks ensue.

Considered the first cyborg novel, The Clockwork Man was first published in 1923 — the same year as Karel Capek’s pioneering android play, R.U.R.

“This is still one of the most eloquent pleas for the rejection of the ‘rational’ future and the conservation of the humanity of man. Of the many works of scientific romance that have fallen into utter obscurity, this is perhaps the one which most deserves rescue.” — Brian Stableford, Scientific Romance in Britain, 1890-1950. “Perhaps the outstanding scientific romance of the 1920s.” — Anatomy of Wonder (1995)

In September 2013, HiLoBooks will publish a gorgeous paperback edition of The Clockwork Man, with a new Introduction by Annalee Newitz, editor-in-chief of the science fiction and science blog io9. Newitz is also author of Scatter, Adapt, and Remember: How Humans Will Survive a Mass Extinction (2013) and Pretend We’re Dead: Capitalist Monsters in American Pop Culture (2006).

SUBSCRIBE to HILOBROW’s serialized fiction via RSS.

ALL EXCERPTS: 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20

“I’m afraid I put you to great inconvenience,” murmured the visitor, still yawning and rolling about on the couch. “The fact is, I ought to be able to produce things — but that part of me seems to have gone wrong again. I did make a start — but it was only a flash in the pan. So sorry if I’m a nuisance.”

“Not at all,” said the Doctor, endeavouring without much success to treat his guest as an ordinary being, “I am to blame. I ought to have realised that you would require nourishment. But, of course, I am still in the dark —”

He paused abruptly, aware that certain peculiar changes were taking place in the physiognomy of the Clockwork man. His strange organism seemed to be undergoing a series of exceedingly swift and complicated physical and chemical processes. His complexion changed colour rapidly, passing from its usual pallor to a deep greenish hue, and then to a hectic flush. Concurrent with this, there was a puzzling movement of the corpuscles and cells just beneath the skin.

The Doctor was scarcely as yet in the mind to study these phenomena accurately. At the back of his mind there was the thought of Mrs. Masters returning with the supper. He tried to resume ordinary speech, but the Clockwork man seemed abstracted, and the unfamiliarity of his appearance increased every second. It seemed to the Doctor that he had remembered a little dimple on the middle of the Clockwork man’s chin, but now he couldn’t see the dimple. It was covered with something brownish and delicate, something that was rapidly spreading until it became almost obvious.

“You see,” exclaimed the Doctor, making a violent effort to ignore his own perceptions, “it’s all so unexpected. I’m afraid I shan’t be able to render you much assistance until I know the actual facts, and even then —”

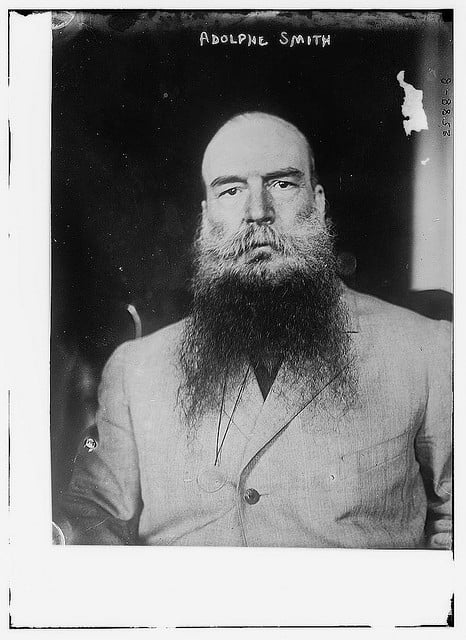

He gripped the back of a chair. It was no longer possible for him to deceive himself about the mysterious appearance on the Clockwork man’s chin. He was growing a beard — swiftly and visibly. Already some of the hairs had reached to his collar. “I beg your pardon,” said the Clockwork man, suddenly becoming conscious of the hirsute development. “Irregular growth — most inconvenient — it’s due to my condition — I’m all to pieces, you know — things happen spontaneously.” He appeared to be struggling hard to reverse some process within himself, but the beard continued to grow.

The Doctor found his voice again. “Great heavens,” he burst out, in a hysterical shout. “Stop it. You must stop it — I simply can’t stand it.”

He had visions of a room full of golden brown beard. It was the most appalling thing he had ever witnessed, and there was no trickery about it. The beard had actually grown before his eyes, and it had now reached to the second button of the Clockwork man’s waistcoat. And, at any moment, Mrs. Masters might return!

Suddenly, with a violent effort involving two sharp flappings of his ears, the Clockwork man mastered his difficulty. He appeared to set in action some swift depilatory process. The beard vanished as if by magic. The doctor collapsed into a chair.

“You mustn’t do anything like that again,” he muttered hoarsely. “You — must — let — me — know — when — you — feel it — coming on.”

In spite of his agitation, it occurred to him that he must be prepared for worse shocks than this. It was no use giving way to panic. Incredible as had been the cricketing performance, the magical flight, and now this ridiculously sudden growth of beard, there were indications about the Clockwork man that pointed to still further abnormalities. The Doctor braced himself up to face the worst; he had no theory at all with which to explain these staggering manifestations, and it seemed more than likely that the ghastly serio-comic figure seated on the couch would presently offer some explanation of his own.

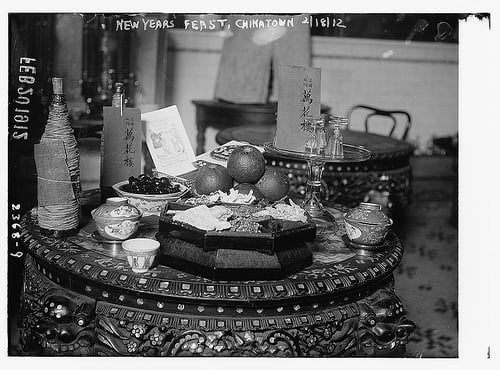

A few moments later Mrs. Masters entered the room bearing a tray with the promised meal. True to her instinct, the good soul must have searched the remotest corners of her pantry in order to provide what she evidently regarded as but an apology of a repast. Little did she know for what Brobdingnagian appetite she was catering! At the sight of the six gleaming white eggs in their cups, the guest made a movement expressive of the direction of his desire, if not of very sanguine hope of their fulfilment. Besides eggs, there were several piles of sandwiches, bread and butter, and assorted cakes.

Mrs. Masters had scarcely murmured her apologies for the best she could do at such short notice, and retired, than the Clockwork man set to with an avidity that appalled and disgusted the Doctor. The six eggs were cracked and swallowed in as many seconds. The rest of the food disappeared in a series of jerks, accompanied by intense vibration of the jaws; the whole process of swallowing resembling the pulsations of the cylinders of a petrol engine. So rapid were the vibrations, that the whole of the lower part of the Clockwork man’s face was only visible as a multiplicity of blurred outlines.

The commotion subsided as abruptly as it had begun, and the Doctor enquired, with as much grace as his outraged instincts would allow, whether he could offer him any more.

“I have still,” said the Clockwork man, locating his feeling by placing a hand sharply against his stomach, “an emptiness here.”

“Dear me,” muttered the Doctor, “you find us rather short at present. I must think of something.” He went on talking, as though to gain time. “It’s quite obvious, of course, that you need more than an average person. I ought to have realised. There would be exaggerated metabolism — naturally, to sustain exaggerated function. But, of course, the — er — motive force behind this extraordinary efficiency of yours is still a mystery to me. Am I right in assuming that there is a sort of mechanism?”

“It makes everything go faster,” observed the Clockwork man, “and more accurately.”

“Quite,” murmured the Doctor. He was leaning forward now, with his elbows resting on the table and his head on one side. “I can see that. There are certain things about you that strike one as being obvious. But what beats me at present is how — and where-” he looked, figuratively speaking, at the inside of the Clockwork man, “mean, in what part of your anatomy the — er — motive force is situated.”

“The functioning principle,” said the Clockwork man, “is distributed throughout, but the clock —” His words ran on incoherently for a few moments and ended in an abrupt explosion that nearly lifted him out of his seat. “Beg pardon — what I mean to say is that the clock — wallabaloo — wum — wum —”

“I am prepared to take that for granted,” put in the Doctor, coughing slightly.

“You must understand,” resumed the Clockwork man, making a rather painful effort to fold his arms and look natural, “you must understand — click — click — that it is difficult for me to carry on conversation in this manner. Not only are my speech centres rather disordered — G-r-r-r-r-r-r — but I am not really accustomed to expressing my thoughts in this way (here there was a loud spinning noise, like a sewing machine, and rising to a rapid crescendo). My brain is — so — constituted that action — except in a multiform world — is bound to be somewhat spasmodic — Pfft — Pfft —Pfft. In fact — Pfft — it is only — Pfft — because I am in such a hope — hope — hopeless condition that I am able to converse with you at all.”

“I see,” said Allingham, slowly, “it is because you are, so to speak, temporarily incapacitated, that you are able to come down to the level of our world.”

“It’s an extra—ordinary world,” exclaimed the other, with a sudden vehemence that seemed to bring about a spasm of coherency.

“I can’t get used to it. Everything is so elementary and restricted. I wouldn’t have thought it possible that even in the twentieth century things would have been so backward. I always thought that this age was supposed to be the beginning. History says the nineteenth and twentieth centuries were full of stir and enquiry. The mind of man was awakening. But it is strange how little has been done. I see no signs of the great movement. Why, you have not yet grasped the importance of the machines.”

“We have automobiles and flying machines,” interrupted Allingham, weakly.

“And you treat them like slaves,” retorted the Clockwork man. “That fact was revealed to me by your callous behaviour towards your motor car. It was not until man began to respect the machines that his real history begun. What ideas have you about the relation of man to the outer cosmos?”

“We have a theory of relativity,” Allingham ventured.

“Einstein!” The Clockwork man’s features altered just perceptibly to an expression of faint surprise. “Is he already born?”

“He is beginning to be understood. And some attempt is being made to popularise his theory. But I don’t know that I altogether agree.”

The Doctor hesitated, aware of the uselessness of dissension upon such a subject where his companion was concerned. Another idea came into his head. “What sort of a world is yours? To look at, I mean. How does it appear to the eye and touch?”

“It is a multiform world,” replied the Clockwork man (he had managed to fold his arms now, and apart from a certain stiffness his attitude was fairly normal). “Now, your world has a certain definite shape. That is what puzzles me so. There is one of everything. One sky, and one floor. Everything is fixed and stable. At least, so it appears to me. And then you have objects placed about in certain positions, trees, houses, lamp-posts — and they never alter their positions. It reminds me of the scenery they used in the old theatres. Now, in my world everything is constantly moving, and there is not one of everything, but always there are a great many of each thing. The universe has no definite shape at all. The sky does not look, like yours does, simply a sort of inverted bowl. It is a shapeless void. But what strikes me so forcibly about your world is that everything appears to be leading somewhere, and you expect always to come to the end of things. But in my world everything goes on for ever.”

“But the streets and houses?” hazarded Allingham, “aren’t they like ours?”

The Clockwork man shook his head. “We have houses, but they are not full of things like yours are, and we don’t live in them. They are simply places where we go when we take ourselves to pieces or overhaul ourselves. They are —” his mouth opened very wide, “the nearest approach to fixed objects that we have, and we regard them as jumping-off places for successive excursions into various dimensions. Streets are of course unnecessary, since the only object of a street is to lead from one place to another, and we do that sort of thing in other ways. Again, our houses are not placed together in the absurd fashion of yours. They are anywhere and everywhere, and nowhere and nowhen. For instance, I live in the day before yesterday and my friend in the day after to-morrow.”

“I begin to grasp what you mean,” said Allingham, digging his chin into his hands, “as an idea, that is. It seems to me that, to borrow the words of Shakespeare, I have long dreamed of such a kind of man as you. But now that you are before me, in the — er — flesh, I find myself unable to accept you.”

The unfortunate Doctor was trying hard to substitute a genuine interest in the Clockwork man for a feeling of panic, but he was not very successful. “You seem to me,” he added, rather lamely, “so very theoretical.”

And then he remembered the sudden growth of beard, and decided that it was useless to pursue that last thin thread of suspicion in his mind. For several seconds he said nothing at all, and the Clockwork man seemed to take advantage of the pause in order to wind himself up to a new pitch of coherency.

“It would be ridiculous,” he began, after several thoracic bifurcations, “for me to explain myself more fully to you. Unless you had a clock you couldn’t possibly understand. But I hope I have made it clear that my world is a multiform world. It has a thousand manifestations as compared to one of yours. It is a world of many dimensions, and every dimension is crowded with people and things. Only they don’t get in each other’s way, like you do, because there are always other dimensions at hand.”

“That I can follow,” said the Doctor, wrinkling his brows, “that seems to me fairly clear. I can just grasp that, as the hypothesis of another sort of world. But what I don’t understand, what I can’t begin to understand, is how you work, how this mechanism which you talk about functions.”

RADIUM AGE SCIENCE FICTION: “Radium Age” is HILOBROW’s name for the 1904–33 era, which saw the discovery of radioactivity, the revelation that matter itself is constantly in movement — a fitting metaphor for the first decades of the 20th century, during which old scientific, religious, political, and social certainties were shattered. This era also saw the publication of genre-shattering writing by Edgar Rice Burroughs, Sax Rohmer, E.E. “Doc” Smith, Jack London, Arthur Conan Doyle, Aldous Huxley, Olaf Stapledon, Karel Čapek, H.P. Lovecraft, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Yevgeny Zamyatin, Philip Gordon Wylie, and other pioneers of post-Verne/Wells, pre-Golden Age “science fiction.” More info here.

HILOBOOKS: The mission of HiLoBooks is to serialize novels on HiLobrow; and also, as of 2012, operating as an imprint of Richard Nash’s Cursor, to reissue Radium Age science fiction in beautiful new print editions. So far, we have published Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague, Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”), Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt, H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook, Edward Shanks’s The People of the Ruins, William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land, and J.D. Beresford’s Goslings. Forthcoming: E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man, Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage, and Muriel Jaeger’s The Man with Six Senses. For more information, visit the HiLoBooks homepage.

SERIALIZED BY HILOBOOKS: Richard Connell’s “The Most Dangerous Game” | Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague | Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”) | Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt | H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook | serialized between March and August 2012; Edward Shanks’ The People of the Ruins, serialized between May and September 2012; William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land, serialized between June and December 2012; J.D. Beresford’s Goslings, serialized between September 2012 and May 2013; E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man, serialized between March and July 2013; and Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage, serialized between March and August 2013.