Theodore Savage (13)

By:

June 3, 2013

HILOBROW is pleased to present the thirteenth installment of our serialization of Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage (also known as Lest Ye Die). New installments will appear each Monday for 25 weeks.

When war breaks out in Europe — war which aims successfully to displace entire populations — British civilization collapses utterly and overnight. The ironically named Theodore Savage, an educated and dissatisfied idler, must learn to survive by his wits in the new England, where 20th-century science, technology, and culture are regarded with superstitious awe and terror.

The book — by a writer best known today for her suffragist plays, treatises, and activism — was published in 1922. In September 2013, HiLoBooks will publish it in a gorgeous paperback edition, with an Introduction by Gary Panter.

SUBSCRIBE to HILOBROW’s serialized fiction via RSS.

ALL EXCERPTS: 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25

They had dragged through the winter in a squalid hardship that, but for the memory of a hardship more dreadful, would have seemed at times beyond bearing; often short of food, with no means of light but their fire, with damp and snow dripping through their ill-built shelters — where they learned, like animals, to sleep through the long dark hours. Through all the winter months their solitude was still unbroken, and if any marauders prowled in the neighbourhood, they passed without knowledge of the hidden camp in the hills.

It was — so far as he could guess — on one of the first sunny days of March that Theodore, the spring lust of movement stirring in his blood, went further from the camp than he had as yet explored; following the stream down its valley into the wide belt of burned land, now rank with coarse grass and yellow dandelions. For an hour or so there was nothing save coarse grass, yellow dandelion and gaunt, dead trees; then a bend of the stream showed him roofs — a cluster of them — and instinctively he halted and crouched behind a tree before making his stealthy approach.

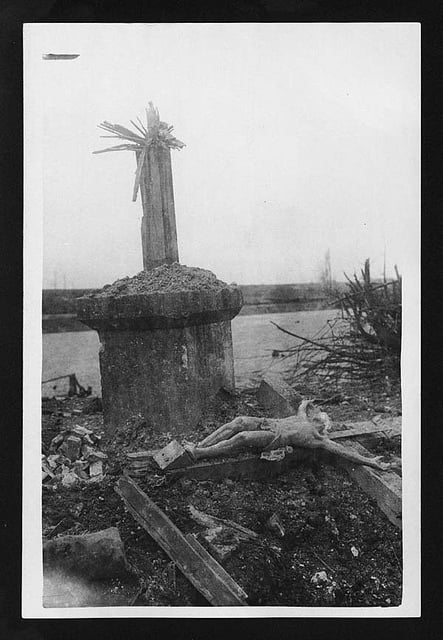

His stealth and precaution were needless. The village from a distance might have passed for uninjured — the flames that had blackened its fields had swept by it, and the houses, for the most part, stood whole; but there was no living man in the long, straggling street, no movement, save of birds and the pattering little scuffle of rats. The indifferent life of beast and bird had taken possession of the dwellings of those who once tyrannized over them; and not only of their dwellings but their bodies. At the entrance of the village half-a-dozen skeletons lay sprawled on the grass-grown road, and a robin sang jauntily from his perch on the breast-bone of a man…. From one end of the street to the other the bones of men lay scattered; in the road, in gardens, on the thresholds of houses — some with tattered rags still fluttering to the wind, some bare bones only, whence the flesh had festered and been gnawed. By a cottage doorstep lay two skeletons touching each other — whereof one was the framework of a child; the little bones that had once been arms reached out to the death’s-head that once had borne the likeness of a woman….

There was a time when Theodore would have turned from the sight and fled hastily; even now, familiar though he was with the ugliness of death, his flesh stirred and crept in the presence of the grotesque litter of bones…. These people had died suddenly, in strange contorted attitudes — here crouching, there outstretched with clawing fingers. Gas, he supposed — a cloud of gas rolling down the street before the wind — and perhaps not a soul left alive!… From an upper window hung a long, fleshless arm: someone had thrust up the casement for air and fallen half across the sill.

It was the indifferent, busy chirping of the nesting birds that helped him to the courage to explore the silent street to its end. It wound, through the village and out of it, to a bridge across a river — into which flowed the smaller stream he had followed since he left his refuge in the hills. From the bridge the road turned with the river and ran down the valley in a south to south-easterly direction; a road grass-grown and empty and bearing no recent trace of the life of man — nothing more recent than the remains of a cart,blackened wood and rusted metal, with the bones of a horse between its shafts.

Below the dead village the valley opened out, the hills receded and were lower; but between them, so far as his eye could discern, the trees were still blackened and lifeless. Down either side the stream the fire-blast had swept without mercy; and, from the completeness with which the country had been seared, Theodore judged that it had been largely cornland, waving with ripe stalks at the moment of disaster and fired after days of dry weather…. All life, save the life of man, teemed in the hot March sun; the herbage thrust bravely to obliterate his handiwork, larks shrilled invisibly and lithe, dark fish were darting through the arches of the bridge. He went only a yard or two beyond the end of the bridge — having, as the sun warned him, reached the limit of distance he could well accomplish if he was to return to the camp by nightfall. On his way back through the village he fought with his repugnance to the grinning company of the dead and turned into one of the silent houses that stood open for any man to enter. Though the dead still dwelt there — stricken down, on the day of disaster before they could reach the open air — there were the usual abundant traces that living men had been there before him; the door had been forced and rooms littered and fouled in the frequent search for clothing and food. All the same, in the hugger-mugger on a kitchen floor he found treasure of string and stuffed the blanket-bag slung over his back with odds and ends of rusting hardware; finally mounting to the floor above the kitchen where, at the head of the staircase, an open door faced him and beyond it a chest of drawers. The drawers had been pulled out and emptied on the floor; what remained of their contents was a dirty litter, sodden by rain when it drove through the window and browned with the dust of many months, and it was not until Theodore had picked up a handful of the litter that he saw it was composed of women’s trifles of underwear. What he held was a flimsy bodice made of soiled and faded lawn with a narrow little edging of lace.

He dropped it, only to pick it up again — remembering suddenly the blanket episode and Ada’s lamentable howls for the garments a wilderness denied her. Perhaps an assortment of dingy finery would do something to allay her craving — and, amused at the thought, he went down on a knee and proceeded to collect an armful. Appropriately the shifting of a heap of yellowed rags revealed a broken hand-glass, lying face downwards on the floor; as he raised it, wondering what Ada would say to a mirror as a gift, its cracked surface showed him a bedstead behind him — not empty!… What was left of the owner of the scraps of lawn and lace was reflected from the oval of the glass.

He snatched up his bag and clattered down the stairs into the open.

It was well past dusk when he trudged up the path that led to the camp and found Ada on the watch at the outskirts of the copse, uneasy at the thought of dark alone.

“You ’ave been a time,” she reproached him sulkily. “The ’ole blessed day — since breakfus. I was beginnin’ to think you’d gone and got lost and I’ve ’ad the fair ’ump sittin’ ’ere by myself and listenin’ to them owls. I ’ate their beastly screechin’; it gives me the creeps.”

“Never mind,” he consoled her, “come along to the fire. I’ve brought you something — a present.”

“Pertaters?” Ada conjectured, still sulky.

“Not potatoes this time,” he told her. “Better than vegetables — something to wear.”

“Something to wear,” she repeated, with no show of enthusiasm. “I suppose that’s another old blanket!”

“Wrong again,” he rejoined, amused by the contempt in her voice. She was still contemptuous when he opened his bag and tossed her a dingy bundle; but as she disentangled it, saw lace and embroidery, she brightened suddenly and knelt down to examine in the firelight; while the sight of the cracked hand-glass brought an instant “Oh!” followed by intent contemplation and much patting and twisting of hair.

Theodore dished supper while she sat and pondered her reflection; and even while she ate hungrily she had eyes and thoughts for nothing but her new possessions. Some were what he had taken them to be — underclothes, for the most part of an ordinary pattern; but mingled with the plainer linen articles were one or two more decorative, lace collars and the like, and it was on these, dingy as they were, that she fell with delight that was open and audible. He watched her curiously when, for the first time since he had known her, he saw her mouth widen in a smile. She was no longer inert, the sullen, lumpish Ada, she was critical, interested, alive; she fingered her treasures, she smoothed them and made guesses at their price when new; she held them up, now this way, now that, for his admiration and her own. Finally, while Theodore stretched his tired length by the camp-fire, she ran off to her shelter for a broken scrap of comb; and when he looked up, a few minutes later, she was posing self-consciously before the hand-glass, with hair newly twisted and a dirty scrap of lace round her neck…. She was another woman as she sat with her rags arranged to show her new frippery; tilting the hand-mirror this way and that and twitching now at the collar and now at her straying ends of hair.

Lying stretched on an arm by the fire, he watched her little feminine antics, amused and taken out of himself; realizing how seldom, till that moment, he had thought of her as a woman, how nearly she had seemed to him an animal only, a creature to be guided and fed; and parrying her eager and insistent demand to be taken to the house where the treasure had been found, that she might see if it contained any more. He had no desire to spoil her pleasure in her finery by the gruesome tale of the manner of its finding; hence, in spite of a curiosity made manifest in coaxing, he held to his refusal stubbornly…. The house was a long way off, he told her — much further than she would care to tramp; then, as she still persisted, maintaining her readiness even for a lengthy expedition, he went on to fiction and explained that the house was in a dangerous condition — knocked about, ruinous, might fall at any moment — and he was not going to say where it was, for her own sake, lest she should be tempted to the peril of an entry.

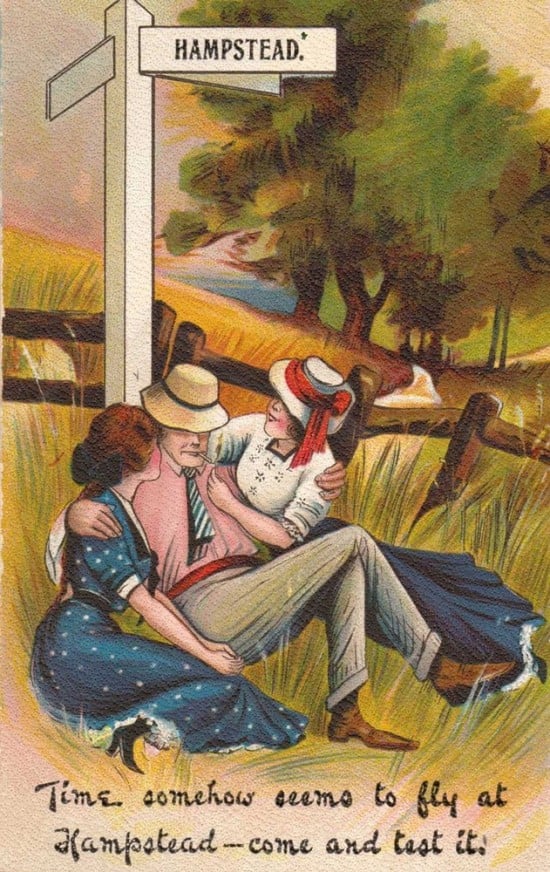

She pouted “You might tell me,” glancing at him from under her lashes; then, as he still persisted in refusal, slapped him on the shoulder for an obstinate boy, turned her back and pretended to sulk. He returned the slap — she expected it and giggled; the next move in the game was his catching of her wrist as she raised her hand for a rejoinder — and for a moment they wrestled inanely, after the fashion of Hampstead Heath…. As he let her go, it dawned on him that this was flirtation as she knew it.

It did not take long for him to realize that they stood to each other, from that night on, in a new and more difficult relation; from foundling and guardian, the leader and led, they had developed into woman and man. For a time fear and hunger had suppressed in Ada the consciousness of sex — which a yard or two of lace and the possession of a hand-glass had revived. Once revived, it coloured her every action, gave meaning to her every word and glance; so that, day by day and hour by hour, the man who dwelt beside her was reminded of bodily desire.

One night when she had left him he lay staring at the fire, faced the situation and wondered if she saw where she was drifting? Possibly — possibly not; she was acting instinctively, from habit. To her (he was sure) a man was a creature to flirt with; an unsubtle attempt to arouse his desire was the only way she knew of carrying on a conversation…. Now that she was woman again — not merely bewildered misery and empty stomach — she had slipped back inevitably to the little giggling allurements of her factory days, to the habits bred in her bone…. With the result?… He put the thought from him, turned over, dog-weary, and slept.

So soon as the next night he saw the result as inevitable; the outcome of life reduced to mere animal living, of nearness, isolation and the daily consciousness of sex. If they stayed together — and how should they not stay together?— it was only a question of time, of weeks at the furthest, of days or it might be hours…. He raised himself to peer through the night at the log-hut that hid and sheltered Ada, wondering if she also were awake. If so, of a certainty, her thoughts were of him; and perhaps she knew likewise that it was only a question of time. Perhaps — and perhaps she just drifted, following her instincts…. He found himself wondering what she would say if she opened her eyes to find him standing at the entrance to her hut, to see him bending over her… now?

He put the thought from him and once more turned over and slept.

With the morning it seemed further off, less inevitable; the sun was hidden behind raw grey mist, and when Ada, shivering and stupid, turned out into the chilly discomfort of the weather she was too much depressed for the exercise of feminine coquetry. The day’s work — hard necessary wood-chopping and equally necessary fishing for the larder — sent his thoughts into other channels, and it was not till he sat at their evening fire — warmed, fed and rested, with no duties to distract him — that he became conscious again, and even more strongly, of the change in their attitude and intercourse. Something new, of expectation, had crept into it; something of excitement and constraint. When their hands touched by chance they noticed it, were instantly awkward; when a silence fell Ada was embarrassed, uncomfortable and made palpable efforts to break it with her pointless giggle. When their eyes met, hers dropped and looked away…. When she rose at last and said good-night he was sure that she also knew. And since they both knew and the end was inevitable, certain…

“You’re not going yet,” he said — and caught at her wrist, laughing oddly.

“It’s late — and I’m sleepy,” she objected with a foolish little giggle; but made no effort to withdraw her wrist from his hold.

“Nonsense,” he told her, “it’s early yet — and you’re better by the fire. Sit down and keep me company for a bit longer.”

She giggled again — more faintly, more nervously — as she yielded to the pull of his fingers and sat down; offering no protest when, instead of releasing her arm, he drew it through his own and held it pressed to his side…. It was a windless night, very silent; no sound but the rush of the little stream below them, now and then a bird-cry and the snap and crackle of their fire. Once or twice Ada tried talking — of a hooting owl, of a buzzing insect — for the sake, obviously, of talking, of hearing a voice through the silence; but as he answered not at all, or by monosyllables, her forced little chatter died away. Even if the thought was not conscious, he knew she was his for the taking.

RADIUM AGE SCIENCE FICTION: “Radium Age” is HILOBROW’s name for the 1904–33 era, which saw the discovery of radioactivity, the revelation that matter itself is constantly in movement — a fitting metaphor for the first decades of the 20th century, during which old scientific, religious, political, and social certainties were shattered. This era also saw the publication of genre-shattering writing by Edgar Rice Burroughs, Sax Rohmer, E.E. “Doc” Smith, Jack London, Arthur Conan Doyle, Aldous Huxley, Olaf Stapledon, Karel Čapek, H.P. Lovecraft, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Yevgeny Zamyatin, Philip Gordon Wylie, and other pioneers of post-Verne/Wells, pre-Golden Age “science fiction.” More info here.

HILOBOOKS: The mission of HiLoBooks is to serialize novels on HiLobrow; and also, as of 2012, operating as an imprint of Richard Nash’s Cursor, to reissue Radium Age science fiction in beautiful new print editions. So far, we have published Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague, Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”), Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt, H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook, Edward Shanks’s The People of the Ruins, William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land, and J.D. Beresford’s Goslings. Forthcoming: E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man, Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage, and Muriel Jaeger’s The Man with Six Senses. For more information, visit the HiLoBooks homepage.

SERIALIZED BY HILOBOOKS: Richard Connell’s “The Most Dangerous Game” | Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague | Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”) | Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt | H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook | serialized between March and August 2012; Edward Shanks’ The People of the Ruins, serialized between May and September 2012; William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land, serialized between June and December 2012; J.D. Beresford’s Goslings, serialized between September 2012 and May 2013; and Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage, serialized between March and August 2013.