The Clockwork Man (10)

By:

May 22, 2013

HILOBROW is pleased to present the tenth installment of our serialization of E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man. New installments will appear each Wednesday for 20 weeks.

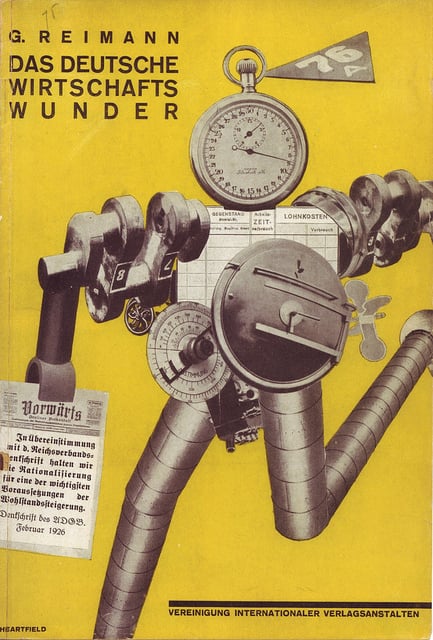

Several thousand years from now, advanced humanoids known as the Makers will implant clockwork devices into our heads. At the cost of a certain amount of agency, these devices will permit us to move unhindered through time and space, and to live complacent, well-regulated lives. However, when one of these devices goes awry, a “clockwork man” appears accidentally in the 1920s, at a cricket match in a small English village. Comical yet mind-blowing hijinks ensue.

Considered the first cyborg novel, The Clockwork Man was first published in 1923 — the same year as Karel Capek’s pioneering android play, R.U.R.

“This is still one of the most eloquent pleas for the rejection of the ‘rational’ future and the conservation of the humanity of man. Of the many works of scientific romance that have fallen into utter obscurity, this is perhaps the one which most deserves rescue.” — Brian Stableford, Scientific Romance in Britain, 1890-1950. “Perhaps the outstanding scientific romance of the 1920s.” — Anatomy of Wonder (1995)

In September 2013, HiLoBooks will publish a gorgeous paperback edition of The Clockwork Man, with a new Introduction by Annalee Newitz, editor-in-chief of the science fiction and science blog io9. Newitz is also author of Scatter, Adapt, and Remember: How Humans Will Survive a Mass Extinction (2013) and Pretend We’re Dead: Capitalist Monsters in American Pop Culture (2006).

SUBSCRIBE to HILOBROW’s serialized fiction via RSS.

ALL EXCERPTS: 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20

Perhaps it was the strong glare of light issuing from the half-open door of the Templar’s Hall that attracted the attention of the Clockwork man as he wandered along towards the lower end of the town. He entered, and found himself in a small lobby curtained off from the main body of the hall. He must have made some slight noise as he stepped upon the bare boards, for the curtain was swept hastily back, and the Curate, who was acting as chief steward of the proceedings, came hurriedly forward.

As he approached the figure standing beneath the incandescent lamp, the clerical beam upon the Curate’s clean-shaven features deepened into a more secular expression of heartfelt relief.

“I’m so glad you have come at last,” he began, in a strong whisper, “I was beginning to be afraid you were going to disappoint us.”

“I am certainly late,” remarked the Clockwork man, “about eight thousand years late, so far as I can judge.”

The Curate scarcely seemed to catch this remark. “Well, I’m glad you’ve turned up,” he went on, “it’s so pitiful when the little ones have to be disappointed, and they have been so looking forward to the conjuring. Your things have arrived.”

“What things?” enquired the Clockwork man.

“Your properties,” said the Curate, “the rabbits and mice, and so forth. They came this afternoon. I had them put on the stage.”

He fingered nervously with his watch, and then his eye rested for a second upon the other’s head gear.

“Excuse me, but you are the conjurer, aren’t you?” he enquired, a trifle anxiously.

Before the Clockwork man had time to reply to this embarrassing question, the curtain was again swiftly drawn, and an anxious female face appeared. “James, has the conjurer — Oh, yes, I see he has. Do be quick, James. The picture is nearly over.”

The face disappeared, and the Curate’s doubts evaporated for the moment. “Will you come this way?” he continued, and led the way through a long, dark passage to the back of the hall. Behind the screen, upon which the picture was being shown, there was a small space, and here a stage had been erected. Upon a small table in the centre stood a large bag and some packages. The Curate adjusted the small gas-jet so as to produce an illumination sufficient to move about. “We must talk low,” he explained, pointing to the screen in front of them, “the cinematograph is still showing. We shall be ready in about ten minutes. Can you manage in that time?”

But the Clockwork man made no reply. He stood in the middle of the stage and slowly lifted a finger to his nose. The Curate’s doubts returned. Something seemed to occur to him as he examined his companion more closely. “You haven’t been taking anything, my good man, have you? Anything of an alcoholic nature?”

“Conjuring,” said the Clockwork man, slowly, “obsolete form of entertainment. Quickness of the hand deceives the eye.”

“Er — yes,” murmured the Curate. He laughed, rather hysterically, and clasped his hands behind his back. “I suppose you do the — er — usual things — gold watches and so forth out of — er — hats. The children have been so looking forward —”

He paused and unclasped his hands. The Clockwork man was looking at him very hard, and his eyes were rolling in their sockets in a most bewildering fashion. There was a long pause.

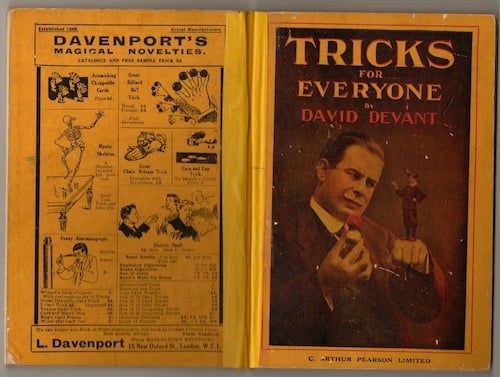

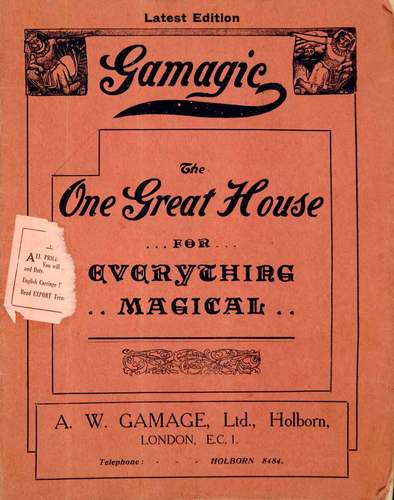

“Dear me,” the Curate resumed at last, “there must be some mistake. You don’t look to me like a conjurer. You see, I wrote to Gamages, and they promised they would send a man. Naturally, I thought when you —”

“Gamages,” interrupted the Clockwork man, “wait —I seem to understand — it comes back to me — universal providers — cash account — nine and ninepence — nine and ninepence — nine and ninepence — I beg your pardon.”

“Really!” The Curate’s jaw dropped several inches. “I must apologise. You see, I’m really rather flurried. I have the burden of this entertainment upon my shoulders. It was I who arranged the conjuring. I thought it would be so nice for the children.” He started rubbing his hands together vigorously, as though to cover up his embarrassment. “Then — then you aren’t the man from Gamages?”

“No,” said the Clockwork man, with a certain amount of dignity, “I am the man from nowhere.”

The Curate’s hands became still. “Oh, dear.” He wrestled with the blankness in his mind. “You’re certainly — forgive me for saying it — rather an odd person. I’m afraid we’ve both made a mistake, haven’t we?”

“Wait,” said the Clockwork man, as the Curate walked hesitatingly towards the door, “I begin to grasp things — conjuring —”

“But are you the conjurer?” asked the Curate, coming back.

“Where I come from,” was the astonishing reply, “we are all conjurers. We are always doing conjuring tricks.”

The Curate’s hands were busy again. “I really am quite at a loss,” he murmured.

“It was a characteristic of the earlier stages of the human race,” said the Clockwork man, as though he were addressing a class of students upon some abstruse subject, “that they exercised the arts of legerdemain, magic, illusion and so forth, purely as forms of entertainment in their leisure hours.”

“Now that sounds interesting,” murmured the Curate, as the other paused, although rather for matter than for breath, “it’s so authoritative — as though it were a quotation from some standard work. All the same, and much as I should like to hear more —”

“It is a quotation,” explained the Clockwork man solemnly, “from a work I was reading when I — when the thing happened to me. It is published by Gamages, and the price is nine and ninepence — nine and ninepence — Oh, bother —”

“I’ll make a note of it,” said the Curate. “But you must really excuse me now. I have so much to see to. There’s the refreshments. The sandwiches are only half cut —”

“It was not until the fifty-ninth century,” continued the Clockwork man, speaking with a just perceptible click, “that man became a conjurer in real life. We have here an instance of the complete turning over of human ideas. Ancient man conjured for amusement; modern man conjures as a matter of course, since the invention of the clock and all that its action implies, including the discovery of at least three new dimensions, or fields of action, man’s simplest act of an utilitarian nature may be regarded as a sort of conjuring trick. Certainly our forefathers, if they could see us as we are now constituted, would regard them as such —”

“So frightfully interesting,” the Curate managed to interpose, “but I really cannot spare the time.” He had reverted now to the alcoholic diagnosis.

“The work in question,” continued the Clockwork man, without taking any notice at all of the other’s impatience, “is of a satirical nature. Its purpose is to awaken people to a sense of the many absurdities in modern life that result from a too mechanical efficiency. It is all in my head. I can spin it all out, word for word —”

“Not now,” hastily pleaded the Curate. “Some other time I should be glad to hear it. I am,” his mouth opened very wide, “a great reader myself. And of course, as a professional conjurer, your interest in such a book would be two-fold.”

“When you asked me if I were a conjurer,” said the Clockwork man, “I at once recalled the book. You see, it’s actually in my head. That is how we read books now. We wear them inside the clock, in the form of spools that unwind. What you have said brings it all back to me. It suddenly occurs to me that I am indeed a conjurer, and that all my actions in this backward world must be regarded in the light of magic.”

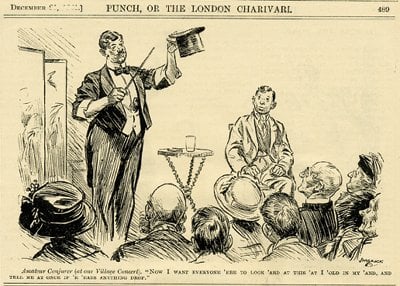

The Curate’s eyebrows shot up in amazement. “Magic?” he queried, with a short laugh. “Oh, we didn’t bargain for magic. Only the usual sleight of hand.”

“You see, I had lost faith in myself,” said the Clockwork man, plaintively. “I had forgotten what I could do. I was so terribly run down.”

“Ah,” said the Curate, kindly, “very likely that’s what it is. The weather has been very trying. One does get these aberrations. But I do hope you will be able to struggle through the performance, for the children’s sake. Dear me, how did you manage to do that?”

The Curate’s last remark was rapped out on a sharp note of fright and astonishment, for the Clockwork man, as though anxious to demonstrate his willingness to oblige, had performed his first conjuring trick.

Now the Curate, apart from a tendency to lose his head on occasion, was a perfectly normal individual. There was nothing myopic about him. The human mind is so constituted that it can only receive certain impressions of abnormal phenomena slowly and through the proper channels. All sorts of fantastic ideas, intuitions, apprehensions and vague suspicions had been dancing upon the floor of the Curate’s brain as he noticed certain peculiarities about his companion. But he would probably not have given them another thought if it had not been for what now happened.

It would require a mathematical diagram to describe the incident with absolute accuracy. The Curate, of course, had heard nothing about the Clockwork man’s other performances; he had scarcely heeded the hints thrown out about the possibility of movement in other dimensions. It seemed to him, in the uncertain light of their surroundings, that the Clockwork man’s right arm gradually disappeared into space. There was no arm there at all. Afterwards, he remembered a brief moment when the arm had begun to grow vague and transparent; it was moving very rapidly, in some direction, neither up nor down, nor this way or that, but along some shadowy plane. Then it went into nothing, evaporated from view. And just as suddenly, it swung back into the plane of the curate’s vision, and the hand at the end of it grasped a silk hat.

The Curate’s heart thumped slowly. “But how did you do it?” he gasped. “And your arm, you know — it wasn’t there!”

So far as the Clockwork man’s features were capable of change, there passed across them a faint expression of triumph and satisfaction. “I perceive,” he remarked, “that I have indeed lapsed into a world of curiously insufficient and inefficent beings. I have fallen amongst the Unclocked. They cannot perceive Nowhere. They do not understand Nowhen. They lack senses and move about on a single plane. Henceforth, I shall act with greater confidence.”

He threw the hat into infinity and produced a parrot cage with parrot.

“Stop it!” the Curate gasped. “My heart, you know — I have been warned — sudden shocks.” He staggered to the wall and groped blindly for an emergency exit, which he knew to be there somewhere. He found it, forced the door open and fell limply upon the pavement outside.

The Clockwork man turned slowly and surveyed the prostrate figure. “A rudimentary race,” he soliloquised, with his finger nose-wards, “half blind, and painfully restricted in their movements. Evidently they have only a few senses — five at the most.” He passed out into the street, carefully avoiding the body.

“They have a certain freedom,” he continued, still nursing his nose, “within narrow limits. But they soon grow limp. And when they fall down, or lose balance, they have no choice but to embrace the earth.”

He waddled along, with his head stuck jauntily to one side. “I have nothing to fear,” he added, “from such a rudimentary race of beings.”

“Evidently,” his thoughts ran on, “they must regard me as an extraordinary being. And, of course, I am — and far superior. I am a superior being suffering from a nervous breakdown.”

He stopped himself abruptly, as though this view of the matter solved a good many problems.

“I must get myself seen to,” he mused, “because, of course, that accounts for everything; my lapse into this defunct order of things and my inability to move about freely in the usual, multiform manner. And it accounts for my absurd behaviour just now.”

He turned slowly, as though considering whether to return and explain matters to the curate. “I must have frightened him,” he whispered, almost audibly, “but I only wanted to show him and the parrot cage happened to be handy.”

He trundled forward again and lurched into the middle of the street.

“Death,” he reflected, “that was death, I suppose. They still die.”

RADIUM AGE SCIENCE FICTION: “Radium Age” is HILOBROW’s name for the 1904–33 era, which saw the discovery of radioactivity, the revelation that matter itself is constantly in movement — a fitting metaphor for the first decades of the 20th century, during which old scientific, religious, political, and social certainties were shattered. This era also saw the publication of genre-shattering writing by Edgar Rice Burroughs, Sax Rohmer, E.E. “Doc” Smith, Jack London, Arthur Conan Doyle, Aldous Huxley, Olaf Stapledon, Karel Čapek, H.P. Lovecraft, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Yevgeny Zamyatin, Philip Gordon Wylie, and other pioneers of post-Verne/Wells, pre-Golden Age “science fiction.” More info here.

HILOBOOKS: The mission of HiLoBooks is to serialize novels on HiLobrow; and also, as of 2012, operating as an imprint of Richard Nash’s Cursor, to reissue Radium Age science fiction in beautiful new print editions. So far, we have published Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague, Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”), Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt, H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook, Edward Shanks’s The People of the Ruins, William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land, and J.D. Beresford’s Goslings. Forthcoming: E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man, Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage, and Muriel Jaeger’s The Man with Six Senses. For more information, visit the HiLoBooks homepage.

SERIALIZED BY HILOBOOKS: Richard Connell’s “The Most Dangerous Game” | Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague | Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”) | Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt | H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook | serialized between March and August 2012; Edward Shanks’ The People of the Ruins, serialized between May and September 2012; William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land, serialized between June and December 2012; J.D. Beresford’s Goslings, serialized between September 2012 and May 2013; E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man, serialized between March and July 2013; and Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage, serialized between March and August 2013.