Theodore Savage (11)

By:

May 20, 2013

HILOBROW is pleased to present the eleventh installment of our serialization of Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage (also known as Lest Ye Die). New installments will appear each Monday for 25 weeks.

When war breaks out in Europe — war which aims successfully to displace entire populations — British civilization collapses utterly and overnight. The ironically named Theodore Savage, an educated and dissatisfied idler, must learn to survive by his wits in the new England, where 20th-century science, technology, and culture are regarded with superstitious awe and terror.

The book — by a writer best known today for her suffragist plays, treatises, and activism — was published in 1922. In September 2013, HiLoBooks will publish it in a gorgeous paperback edition, with an Introduction by Gary Panter.

SUBSCRIBE to HILOBROW’s serialized fiction via RSS.

ALL EXCERPTS: 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25

Theodore lived through the winter — as all his fellows lived — destructively, on the legacy and remnant of other men’s savings and makings; scraping and grubbing in other men’s ground, burning furniture and wood-work, the product of other men’s labours, and taking no thought for the morrow. At the beginning of winter some four or five score of human shadows, men and women, crept about the dead streets and the fields beyond them in their daily quest for the means to keep life in their bodies; but, as the weeks drew on and the winter hardened, starvation and the sickness born of starvation reduced their numbers by a half. Those lived best who were most skilful at the trapping of vermin; and they had long been existing on little but rat-flesh, when some hunters of rats, on the track of their prey, discovered a treasure beyond price — a godsend — in the shape of sacks of grain in the cellar of an empty brewery.

The discovery meant more than a supply of food and the staving-off of death by starvation; with the possession of resources that, with care, might last for weeks there came into being a common interest, the fellowship that makes a social system. After the first wild struggle — the rush to fill their hands and cram their gnawing stomachs — the shadows and skeletons of men controlled their instincts and took counsel; the fact that their stomachs were full and their craving satisfied gave back to them the power of construction, of fore-thought and restraint; they ceased to be instinctively inimical and wholly animal and took common measures for the preservation and rationing of their heaven-sent windfall. They advised, consulted, heard opinion and gave it, were reasonable; counted their numbers in relation to the size of their hoard; and in the end decided, by common consent, on the amount of the daily portion which was to be allotted to each in return for his share in the duty of guarding it — against the cravings of their own hunger as well as against the inroads of rats and mice…. With food — with property — they were human again; capable of plans for the morrow, of concerted and intelligent action. The enmity they had hitherto felt against each other was suddenly transferred to the stranger — the foreigner — who might force his way in and acquire a share in their treasure. Hence they took precautions against the arrival of the stranger, kept watch and ward on the outskirts of the town and drove away the chance newcomer, so that the knowledge of their good fortune should not spread. With duties shared, the dead sense of comradeship revived; they began to recognize and greet each other as they came for their daily portion. And if some were restrained only by the common watchfulness from appropriating more than their share of the common stock, there were others in whom stirred the sense of honour.

For a week or more they lived under the beginnings of a social system which was rendered possible by their certainty of a daily mess; and then came what, perhaps, was inevitable — discovery of pilfering from the store that gave life to them all. The pilferers, detected by the night-guard, fled on the instant, well knowing that their sin against the very existence of the little community was a sin beyond hope of forgiveness; they eluded pursuit in the darkness and by morning had vanished from the neighbourhood. For the time only; since they took with them the knowledge of the hoarded grain they had forfeited — a knowledge which was power and a weapon to themselves, a danger to those they had fled from. Two days later, after nightfall, a skeleton rabble, armed with knives, clubs and stones, was led into the town by the renegades; and there was fought out a fierce, elementary battle, a struggle of starved men for the prize of life itself…. From the first the case of the defenders was hopeless; outnumbered and taken by surprise, they were beaten in detail, overwhelmed — and in less than five minutes the survivors were flying for their lives, the darkness their only hope of safety.

Theodore Savage was of the remnant who owed their lives to darkness and the speed with which they fled. As he neared the outskirts of the town and slackened, exhausted, to draw breath, he heard the patter of running steps behind him and for a moment believed himself pursued — till a passing burst of moonlight showed the runner as a woman, like himself seeking safety in flight. A young woman, with a sobbing open mouth, who clutched at his arm and besought him not to leave her to be killed — to save her, to get her away! … He knew her by sight as he knew all the members of the destitute little community — a girl with a face once plump, now hollowed, whom he had seen daily when she came, in stupid wretchedness, to hold out her bowl for her share of the common ration; one of a squalid company of three or four women who herded together — and whose habit of instinctive fellowship was broken by the sudden onslaught which had driven them apart in flight.

“I don’t know where they’ve all gone,” she wailed. “Don’t leave me — for Gawd’s saike don’t leave me…. Ow, whatever shall I do? … I dunno where to go — for Gawd’s sake…”

He would gladly have been rid of her lamenting helplessness but she clung to him in a panic that would not be gainsaid, as fearful almost of the lonely dark ahead as of the bloody brawl she had fled from.

“Hold your tongue,” he ordered as he pulled her along. “Don’t make that noise or they’ll hear us. And keep close to me — keep in the shadow.”

She obeyed and stilled her sobbing to gasps and whimpers — holding tightly to his arm while he hurried her through by-streets to the open country. He knew no more than she where they were going when they left the silent outskirts of the town behind them, and, pressing against each other for warmth, bent their heads to a January wind.

That night for Theodore Savage was the beginning of an odd partnership, a new phase of his life uncivilized. The girl who had clutched at him as the drowning clutch at straws was destined to bear him company for more than a winter’s night and a journey to comparative safety; being by nature and training of the type that clings, as a matter of right, to whomsoever will fend for it, she drifted after him instinctively. When she woke in the morning in the shelter he had found for her she looked round for him to guide and, if possible, feed her — and awaited his instructions passively.

One human being — so it did not threaten him with violence — was no more to him than another, and perhaps he hardly noticed that when he rose and moved on she followed. From that hour forth she was always at his heels — complaining or too wretched to complain. He would let her hang on his arm as they trudged and shared his findings of food with her — because she had followed, was there; and it was some time before he realized that he had shouldered a responsibility which had no intention of shifting itself from his back…. When he realized the fact he had already tacitly accepted it; and for the first few weeks of their existence in common he was too fiercely occupied in the task of keeping them both alive to consider or define his relationship to the creature who whimpered and stumbled at his heels and took scraps of food from his hands. When, at last, he considered it, the relationship was established on both sides. She was his dependent, after the fashion of a child or an accustomed dog; and having learned to look to him for food, for guidance and protection, she could be cast off only by direct cruelty and the breaking of a daily habit.

In the beginning that was all; she followed because she did not know what else to do; he led and they hungered together. For the most part they were silent with the speechlessness of misery, and it was days before he even asked her name, weeks before he knew more of her life in the past than was betrayed by a Cockney accent. So long as existence was a craving and a fear, where nothing mattered save hunger and the fending-off of present death, the fact that she was a woman meant no more to him than her dependence and his own responsibility; thus her companionship was no more than the bodily presence of a human being whose needs were his own, whose terrors and whose enemies were his.

They prowled and starved together through the long bitterness of winter in a world stripped bare of its last year’s harvest where all hungry mouths strove to keep other mouths at a distance; and time and again, when they grubbed for food or sought to take shelter, they were driven away with threats and with violence by those who already held possession of some tract of street or country. No claim to ownership could stand against the claim of a stronger, and one man, meeting them, would avoid them, slink out of their way — because, being two, they could strip him if the mood should take them. And when they, in their turn, sighted three or four figures in the distance, they made haste to take another road.

Once, when a solitary wayfarer shrank from them and scuttled to the cover of a ragged patch of firewood, there came back to Theodore, like a rushing mighty wind, the memory of his last days in London, the thought of his journey down to York. The strange, glad fellowship of the outbreak of war, the eagerness to serve and be sacrificed; the friendliness of strangers, the dear love of England, the brotherhood!… The creature who scuttled at his very sight would have been his brother in those first days of splendid sacrifice! “Lord God!” he said and laughed long and uncontrollably; while the girl, Ada, stared in open-mouthed bewilderment — then pulled at his arm and began to cry, believing he was going off his head.

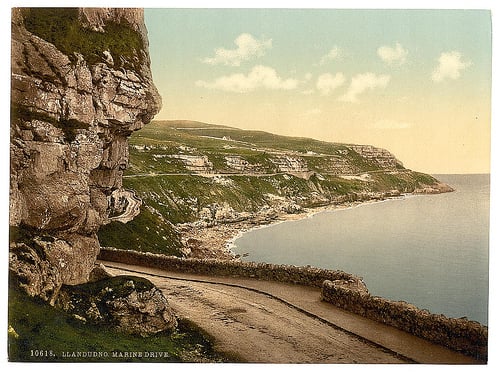

In their hunted and fugitive life their wanderings, of necessity, were planless; they drifted east or west, by this road or that, as fear, the weather or the cravings of their hunger prompted. They sought food, thought food only and, as far as possible, avoided the neighbourhood of those, their fellow-men, who might try to share their meagre findings. House-room, bare house-room, stood ready for their taking in the country as well as in the town; but wherever there was more than house-room — food or the mere possibility of food — the human wolf was at hand to dispute it with his rivals. There was a time when a road, followed blindly, led them down to the sea and the corpse of a pretentious little watering-place — where stiff, blank terraces of ornate brick and plaster stared out at the unbroken sea-line; they found themselves shelter in a bow-windowed villa that still bore the legend “Ocean View: Apartments,” trudged along the tide-mark in search of sand-crabs and fished from an iron-legged pier. When a long winter gale swept the pier with breakers and put a stop to their fishing, they turned and tramped inland again…. And there was another time when they were the sole inhabitants of a stretch of Welsh mining-village — they knew it for Welsh by the street-names — where they hunted their rats and grubbed for roots in allotments already trampled over. For very starvation they moved on again; and later — how much later they could not remember — took shelter, because they could go no further, in a cottage on the outskirts of a moor-land hamlet, where they were almost at extremity when a bitter spell of cold, at the end of winter, sent them food in the shape of frozen rooks and starlings. And, a day or two later, they were driven out again; Theodore, searching for dead birds in the snow, met others engaged in the same hungry quest — other and earlier settlers in the neighbourhood who saw in him a poacher on their scanty hunting-grounds and, gathering together in a common hate and need, fell on the intruders and chased them out with stones and threats. Theodore and the girl were hunted from their homestead and out on to the bleakness of the moor; whence, looking back breathless and aching from their bruises, they saw half a dozen yelling starvelings who still threatened them with shouts and upraised fists…. They went on blindly because they dared not stay; and that, for many days, was the last they saw of mankind.

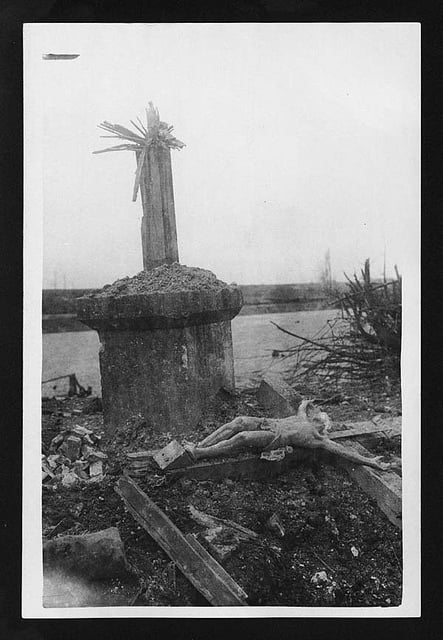

It must have been towards the end of February or the beginning of March that they ended their long goings to and fro and found the refuge that, for many months, was to give them hiding and sustenance. Since they had been driven from their last shelter they had sighted no enemy in the shape of a living man, but the days that followed their flight had been almost foodless; and in the end they had come near to death from exposure on a stretch of hill and heath-covered country where they lost all sense of direction or even of desire. There, without doubt, they would have left their bones if there had not already been a promise of spring in the air; as it was, they could hardly drag themselves along when the moor dropped suddenly into a valley, a wide strip of land once pasture, now bleak and blackened from the passing of the poison-fire which had seared it from end to end. Here and there were charred mummies of men and of animals, lying thickest round a farmhouse, partly burned out; but beyond the burned farmhouse was a stream that might yield them fish; and with the warmth that was melting the snow on the hilltops little shafts of green life were piercing through the blackened soil. Before dark, in what once had been a garden, they scraped with their nails and their knives and found food — worm-eaten roots that would once have seemed unfit for cattle, that they thrust into their mouths unwashed. They sheltered for the night within the skeleton walls of the farm ; and when, with morning, they crawled into the sun, the last patch of snow had vanished from the hills and the tiny shafts of green were more radiant against the blackened soil…. The long curse and barrenness of winter was over and Nature was beginning anew her task of supporting her children.

RADIUM AGE SCIENCE FICTION: “Radium Age” is HILOBROW’s name for the 1904–33 era, which saw the discovery of radioactivity, the revelation that matter itself is constantly in movement — a fitting metaphor for the first decades of the 20th century, during which old scientific, religious, political, and social certainties were shattered. This era also saw the publication of genre-shattering writing by Edgar Rice Burroughs, Sax Rohmer, E.E. “Doc” Smith, Jack London, Arthur Conan Doyle, Aldous Huxley, Olaf Stapledon, Karel Čapek, H.P. Lovecraft, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Yevgeny Zamyatin, Philip Gordon Wylie, and other pioneers of post-Verne/Wells, pre-Golden Age “science fiction.” More info here.

HILOBOOKS: The mission of HiLoBooks is to serialize novels on HiLobrow; and also, as of 2012, operating as an imprint of Richard Nash’s Cursor, to reissue Radium Age science fiction in beautiful new print editions. So far, we have published Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague, Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”), Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt, H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook, Edward Shanks’s The People of the Ruins, William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land, and J.D. Beresford’s Goslings. Forthcoming: E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man, Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage, and Muriel Jaeger’s The Man with Six Senses. For more information, visit the HiLoBooks homepage.

SERIALIZED BY HILOBOOKS: Richard Connell’s “The Most Dangerous Game” | Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague | Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”) | Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt | H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook | serialized between March and August 2012; Edward Shanks’ The People of the Ruins, serialized between May and September 2012; William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land, serialized between June and December 2012; J.D. Beresford’s Goslings, serialized between September 2012 and May 2013; and Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage, serialized between March and August 2013.