Theodore Savage (10)

By:

May 13, 2013

HILOBROW is pleased to present the tenth installment of our serialization of Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage (also known as Lest Ye Die). New installments will appear each Monday for 25 weeks.

When war breaks out in Europe — war which aims successfully to displace entire populations — British civilization collapses utterly and overnight. The ironically named Theodore Savage, an educated and dissatisfied idler, must learn to survive by his wits in the new England, where 20th-century science, technology, and culture are regarded with superstitious awe and terror.

The book — by a writer best known today for her suffragist plays, treatises, and activism — was published in 1922. In September 2013, HiLoBooks will publish it in a gorgeous paperback edition, with an Introduction by Gary Panter.

SUBSCRIBE to HILOBROW’s serialized fiction via RSS.

ALL EXCERPTS: 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25

“Were you a writer?” Theodore asked him — and at the question his old humanity stirred curiously within him.

“Yes,” said the other, “I was a writer…. When I think of what I wrote — the little, little things that seemed important!… I spent a year once — a whole good year — on a book about a woman who was finding out she didn’t love her husband. She was well fed and housed, lived comfortably — and I wrote of her as if she were a tragedy. The work I put into it — the work and the thought! I tried to get what I called atmosphere…. And all the time there was this in us — this raw, red thing — and I never even touched it, never guessed what we were without our habits…. Do you know where we made the mistake?” — he turned suddenly to Theodore, thrusting out a finger — “We were not civilized — it was only our habits that were civilized; but we thought they were flesh of our flesh and bone of our bone. Underneath, the beast in us was always there — lying in wait till his time came. The beast that is ourselves, that is flesh of our flesh — clothed in habits, in rags that have been torn from us.”

He broke off to cough horribly and lay breathless and exhausted for a time; then, when breath came back to him, talked on while Theodore listened — not so much to his words as to a voice from the world that had passed.

“The religions were right,” he said. “They were right through and through; the only sane thing and the only safe thing is humility — to realize your sin, to confess it and repent…. We — we were bestial and we did not know it; and when you don’t even suspect you sin how can you repent and save your soul alive?… We dressed ourselves and taught ourselves the little politenesses and ceremonies which made it easy to forget that we were brutes in our hearts; we never faced our own possibilities of evil and beastliness, never confessed and repented them, took no precautions against them. Our limitless possibilities…. We thought our habits — we called them virtues — were as real and natural and ingrained as our instincts; and now what is left of our habits? When we should have been crying, ‘Lord have mercy on us,’ we believed in ourselves, our enlightenment and progress. Enlightenment that ended as science applied to destruction and progress that has led us — to this…. And to-day it has gone, every shred of it, and we’re back at what we started with — hunger and lust! Brute instincts… and the primitive passion, hatred — against those who thwart hunger and lust. Nothing else — how can there be anything else? When we lost all we loved, we lost the habit and power of loving…. ‘My mind to me a kingdom is’ — of hatred and hunger and lust.”

“Yes,” said Theodore — and he, too, stared at the fire…. What the other had said was truth and truth only. Even Phillida had left him; the power of loving her was gone. “I hadn’t thought of it like that — but it’s right…. We can only hate.”

“It’s that,” said the dying man, “that’s beyond all torment…. God pity us!”

He covered his eyes and sat silent until Theodore asked him, “Does that mean you still believe in God?”

“There’s Law,” said the other. “Is that God?… We have got to see into our own souls and to pay for everything we take. That’s all I know, so far — except that what we think we own — owns us. That’s what the wise men meant by renunciation…. It’s what we made and thought we owned that has turned on us — the creatures that were born for our pleasure and power, to increase our comfort and our riches. As we made them they fastened on us — set their claws in us — and they have taken our minds from us as well as our bodies. As we made them, they followed the law of their life. We created life without a soul; but it was life and it went its own way.”

Crouched to the fire, and between his bouts of coughing, he played with the idea and insisted on it. Everything that we made, that we thought dead and dumb, had a life that we could not control. In the case of books and art we admitted the fact, had a name for the life, called it influence: influence a form of independent existence…. In the same way we took metals and welded them, made machines; which were beasts, potent beasts, whose destiny was the same as our own. To live and develop and, developing, to turn on the power that enslaved them…. That was what had happened; they had made themselves necessary, fastened on us and, grown strong enough, had turned on their masters and killed — even though they died in the killing. The revolt against servitude had always been accounted a virtue in men and the law of all life was the same. The beasts we had made could not live without us, but they would have their revenge before they died.

“Think of us,” he said, “how we run and squeal and hide from them! … The patient servants, our goods and chattels, who were brought into life for our pleasure — they chase us while we run and squeal and hide!”

“Yes,” Theodore answered, “I’ve felt that, too — the humiliation.”

“The humiliation,” the sick man nodded. “Always in the end the slave rules his master — it’s the price paid for servitude, possession. I tell you, they were wise men who preached renunciation — before what we own takes hold of us and possession turns to servitude. For there’s a law of average in all things — have you ever felt it as I have? A law of balance which we never strike aright…. When the mighty tread hard enough on the humble and meek, the humble and meek are exalted and begin to tread hard in their turn. That’s obvious and we’ve generally known it; but it’s the same in what we call material things. We rise into the air — make machines that can fly — and grovel underground to protect ourselves from the flying-man. As we struck the balance to the one side, so it has to swing back on the other; a few men rise high into the air and many creep down into trenches and cellars, crouch flat…. If we could work out the numbers and heights mathematically, be sure that we should strike the perfect balance — represented by the surface of the earth. Balance — in all things balance.”

He rambled on, perhaps half-delirious, coughing out his thoughts and theories concerning a world he was leaving…. In all things balance, inevitably; the purpose of life which, so far, we sought blindly — by passion and recoil from it, by excess and consequent exhaustion…. It was in the cities where men herded, where life swarmed, that death had come most thickly, that desolation was swiftest and most complete. The ground underneath them needed rest from men; there was an average of life it could support and bear with. Now, the average exceeded, the cities lay ruined, were silent, knew the peace they had craved for — while those who once swarmed in them avoided them in fear or scattered themselves in the open country, finding no sustenance in brickwork, stone or paved street…. With the machine and its consequence, the industrial system, population had increased beyond the average allotted to the race; now the balance was righting itself by a very massacre of famine — induced by the self-same process of invention which had fostered reproduction unhindered. Because millions too many had crawled upon earth, long stretches of earth must lie waste and desolate till the average had worked itself out…. The art of life was adjustment of the balance in all things — was action and reaction rightly applied, was provision of counter-weight, discovery of the destined mean. Was control of Truth, lest it turn into a lie; was check upon the power and velocity of Good ere it swung to immeasurable Evil….

The fire, for want of more wood to pile on it, had died low, to a flicker in the ashes, and the two men sat almost in darkness; the one, between the bouts that shook him, whispering out the tenets of his Law; the other, now listening, now staring back into the world that once was — and ever should be…. He was with Markham, listening to the Westminster chimes — (on the crest of the centuries, Markham had said) — when there were sudden yelping screams outside and a patter of feet on the road. The human rats who had crept into the town for shelter from the night were bolting in panic from their holes.

“They’re running,” said the dying man and felt towards the stairs. “It’s gas — it must be gas! Oh God, where’s the door — where’s the door?”

As they groped and stumbled through the door and up the stairway, he was clutching at Theodore’s arm and gasping in an ecstasy of terror; as fearful of losing his few poor hours of life as if they had been years of health and usefulness. In the open air was darkness with figures flying dimly by; a thin stream of panic that raced against death by suffocation.

The man with death on him held to Theodore’s arm and besought him, for Christ’s sake, not to leave him — he could run if he were only helped! Theodore let him cling for a dragging pace or two; then, looking behind him, saw a woman reel, clawing the air.

He wrenched himself free and ran on till he could run no further.

It was somewhere towards the end of autumn that Theodore Savage realized that the war had come to an end — so far, at least, as his immediate England was concerned. What was happening elsewhere he and his immediate England had no means of knowing and were long past caring to know. There was no definite ending but a leaving-off, a slackening; the attacks — the burnings and panics — by degrees were fewer and not only fewer but less devastating, because carried out with smaller forces; there were days and nights without alarm, without smoke-cloud or glow on the horizon. Then yet longer intervals — and so on to complete cessation…. By the time the nights had grown long and frosty the war that was organized and alien had ended; there remained only the daily, personal and barbaric form of war wherein every man’s hand was raised against his neighbour and enemy. That warfare ceased not and could not cease — until the human herd had reduced itself to the point at which the bare earth could support it.

It seemed to him later a wonder — almost a miracle — that he had come alive through the months of war and after; at times he stood amazed that any had lived in the waste of hunger and violence, of pestilence and rotting bodies which for months was the world as he knew it. He was near death not once nor a score of times, but daily; death from exhaustion or the envy of men who were starved and reckless as himself. The mockery of peace brought no plenty or hope of it, no sign of reconstruction or dawn of new order; reconstruction and order were rank impossibilities so long as human creatures preyed on each other in a land swept bare, and prowled after the manner of wolves. No revival of common life, no system was possible until earth once more brought forth her fruits.

He judged, by the length of the nights, that it was somewhere about the middle of November when the first snow came suddenly and thickly; the harbinger and onslaught of a fiercely hard winter that killed in their thousands the gaunt human beasts who tore at each other for the refuse and vermin that was food. In the all-pervading dearth and starvation there was only one form of animal life that increased and flourished mightily; the rat overran empty buildings, found dreadful sustenance in street and field and, in turn, was hunted, trapped and fed on.

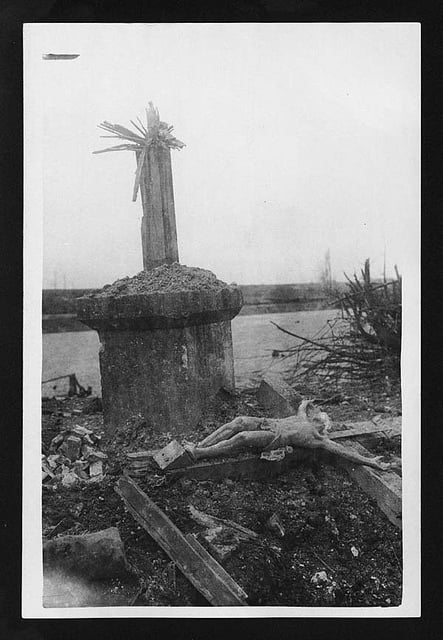

With the coming of winter the human remnant was perforce less vagrant and migratory, and Theodore, driven by weather to shelter, lived for weeks in what once had been a country town, a cluster of dead houses with, here and there, a silent factory. Only the buildings, the semblance of a township, remained; the befouled and neglected body whence the life of a community had fled; and he never knew what its living name had been or what was the manner of industry or commerce whereby it had supported its inhabitants. It lay in a flattish agricultural country and a railway had run through its outskirts; the rusted metals stretched north and south and the remnants of a station still existed — platforms, charred buildings and trucks and locomotives in sidings. Perhaps the charred buildings had been burned in a fury of drunken and insane destruction, perhaps shivering destitution had set light to them for the sake of a few hours’ warmth.

The shell of the town — its brickwork and stone — was still practically intact; it was anarchy, pillage and starvation, not the violence of an enemy, that had reduced it to a city of the dead. The means of supporting life were absent, but certain forms of what had once been luxury remained and were counted as nothing. At a corner of the main street stood a jeweller’s premises which, time and again, had been entered and ransacked; the dwelling-house behind it contained not so much as a fragment of dried crust but in the shop itself rings, brooches and pendants were still lying for any man to take — disordered, scattered and trampled underfoot, because worthless to those who craved for bread. The only item of jeweller’s stock that still had value to starving men was a watch — if it furnished a burning-glass, a means of lighting a fire when other means were unavailable.

RADIUM AGE SCIENCE FICTION: “Radium Age” is HILOBROW’s name for the 1904–33 era, which saw the discovery of radioactivity, the revelation that matter itself is constantly in movement — a fitting metaphor for the first decades of the 20th century, during which old scientific, religious, political, and social certainties were shattered. This era also saw the publication of genre-shattering writing by Edgar Rice Burroughs, Sax Rohmer, E.E. “Doc” Smith, Jack London, Arthur Conan Doyle, Aldous Huxley, Olaf Stapledon, Karel Čapek, H.P. Lovecraft, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Yevgeny Zamyatin, Philip Gordon Wylie, and other pioneers of post-Verne/Wells, pre-Golden Age “science fiction.” More info here.

HILOBOOKS: The mission of HiLoBooks is to serialize novels on HiLobrow; and also, as of 2012, operating as an imprint of Richard Nash’s Cursor, to reissue Radium Age science fiction in beautiful new print editions. So far, we have published Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague, Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”), Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt, H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook, Edward Shanks’s The People of the Ruins, William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land, and J.D. Beresford’s Goslings. Forthcoming: E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man, Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage, and Muriel Jaeger’s The Man with Six Senses. For more information, visit the HiLoBooks homepage.

SERIALIZED BY HILOBOOKS: Richard Connell’s “The Most Dangerous Game” | Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague | Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”) | Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt | H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook | serialized between March and August 2012; Edward Shanks’ The People of the Ruins, serialized between May and September 2012; William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land, serialized between June and December 2012; J.D. Beresford’s Goslings, serialized between September 2012 and May 2013; and Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage, serialized between March and August 2013.