Theodore Savage (5)

By:

April 8, 2013

HILOBROW is pleased to present the fifth installment of our serialization of Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage (also known as Lest Ye Die). New installments will appear each Monday for 25 weeks.

When war breaks out in Europe — war which aims successfully to displace entire populations — British civilization collapses utterly and overnight. The ironically named Theodore Savage, an educated and dissatisfied idler, must learn to survive by his wits in the new England, where 20th-century science, technology, and culture are regarded with superstitious awe and terror.

The book — by a writer best known today for her suffragist plays, treatises, and activism — was published in 1922. In September 2013, HiLoBooks will publish it in a gorgeous paperback edition, with an Introduction by Gary Panter.

SUBSCRIBE to HILOBROW’s serialized fiction via RSS.

ALL EXCERPTS: 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25

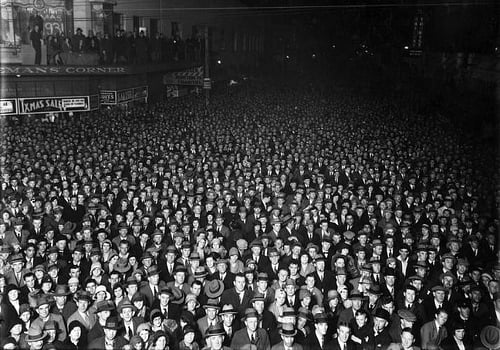

Through the half-open window came the hum and murmur of the crowd that waited for the hour…. Theodore stirred restlessly, conscious of the unseen turning of countless faces to the clock — and aware, through the murmur, of the frenzied little beating of his watch…. He hesitated to look at it — and when he drew it out and said “Five minutes more,” his voice sounded oddly in his ears.

“Five minutes,” said Markham…. He laughed suddenly and pushed the bottle across the table. “Do you know where we are now — you and I and all of us? On the crest of the centuries. They’ve carried us a long roll upwards and now here we are — on top! In five more minutes — three hundred little seconds — we shall hear the crest curl over…. Meanwhile, have a drink!”

He checked himself and held up a finger. “Your watch is slow!”

The hum and murmur of the crowd had ceased and through silence unbroken came the prayer of the Westminster chime.

Lord — through — this — hour

Be —Thou — our — guide,

So — by —Thy — power

No — foot — shall — slide.

There was no other sound for the twelve booming strokes of the hour: it was only as the last beat quivered into silence that there broke the moving thunder of a multitude.

“Over!” said Markham. “Hear it crash? … Well, here’s to the centuries — after all, they did the best they knew for us!”

The war-footing arrangements of the Distribution Office included a system of food control involving local supervision; hence provincial centres came suddenly into being, and to one of these — at York —Theodore Savage was dispatched at little more than an hour’s notice on the morning after war was declared. He telephoned Phillida and they met at King’s Cross and had ten hurried minutes on the platform; she was still eager and excited, bubbling over with the impulse to action — was hoping to start training for hospital work — had been promised an opening — she would tell him all about it when she wrote. Her excitement took the bitterness out of the parting — perhaps, in her need to give and serve, she was even proud that the sacrifice of parting was demanded of her…. The last he saw of her was a smiling face and a cheery little wave of the hand.

He made the journey to York with a carriageful of friendly and talkative folk who, in normal days, would have been strangers to him and to each other; as it was, they exchanged newspapers and optimistic views and grew suddenly near to each other in their common interest and resentment…. That was what war meant in those first stirring days — friendliness, good comradeship, the desire to give and serve, the thrill of unwonted excitement…. Looking back from after years it seemed to him that mankind, in those days, was finer and more gracious than he had ever known it — than he would ever know it again.

The first excitement over, he lived somewhat tediously at York between his office and dingily respectable lodgings; discovering very swiftly that, so far as he, Theodore Savage, was concerned, a state of hostilities meant the reverse of alarums and excursions. For him it was the strictest of official routine and the multiplication of formalities. His hours of liberty were fewer than in London, his duties more tiresome, his chief less easy to get on with; there was frequent overtime, and leave — which meant Phillida — was not even a distant possibility. For all his honest desire of service he was soon frankly bored by his work; its atmosphere of minute regularity and insistent detail was out of keeping with the tremor and uncertainty of war, and there was something aesthetically wrong about a fussy process of docketing and checking while nations were at death grips and the fate of a world in the balance…. His one personal satisfaction was the town, York itself — the walls, the Bars, and above all the Minster; he lodged near the Minster, could see it from his window, and its enduring dignity was a daily relief alike from the feverish perusal of war news, his landlady’s colour-scheme and taste in furniture and the fidgety trifling of the office.

In the evening he read many newspapers and wrote long letters to Phillida; who also, he gathered, had discovered that war might be tedious. “We haven’t any patients yet,” she scribbled him in one of her later letters, “but, of course, I’m learning all sorts of things that will be useful later on, when we do get them. Bandaging and making beds — and then we attend lectures. It’s rather dull waiting and bandaging each other for practice — but naturally I’m thankful that there aren’t enough casualties to go round. Up to now the regular hospitals have taken all that there are —’temporaries’ like us don’t get even a look in…. The news is really splendid, isn’t it?”

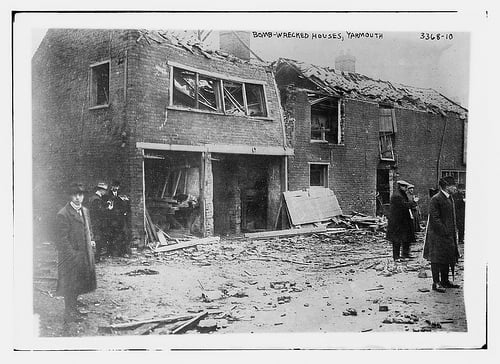

There were few casualties in the beginning because curiously little happened; Western Europe was removed from the actual stormcentre, and in England, after the first few days of alarmist rumours concerning invasion by air and sea, the war, for a time, settled down into a certain amount of precautionary rationing and a daily excitement in newspaper form — so much so that the timorous well-to-do, who had retired from London on the outbreak of hostilities, trickled back in increasing numbers. Hostilities, in the beginning, were local and comparatively ineffective; one of the results of the limitation of troops and armaments enforced by the constitution of the League was to give to the opening moves of the contest a character unprepared and amateurish. The aim, on either side, was to obtain time for effective preparation, to organize forces and resources; to train fighters and mobilize chemists, to convert factories, manufacture explosive and gas, and institute a system of co-operation between the strategy of far-flung allies. Hence, in the beginning, the conflict was partial and, as regards its strategy, hesitating; there were spasms of bloody incident which were deadly enough in themselves, but neither side cared to engage itself seriously before it had attained its full strength…. First blood was shed in a fashion that was frankly mediaeval; the heady little democracy whose failure to establish a claim in the Court of Arbitration had been the immediate cause of the conflict, flung itself with all its half-civilized resources upon its neighbour and enemy, the victorious party to the suit. Between the two little communities was a treasured feud which had burst out periodically in defiance of courts and councils; and, control once removed, the border tribesmen gathered for the fray with all the enthusiasm of their rude forefathers, and raided each other’s territory in bands armed with knives and revolvers. Their doings made spirited reading in the press in the early days of the war — before the generality of newspaper readers had even begun to realize that battles were no longer won by the shock of troops and that the root-principle of modern warfare was the use of the enemy civilian population as an auxiliary destructive force.

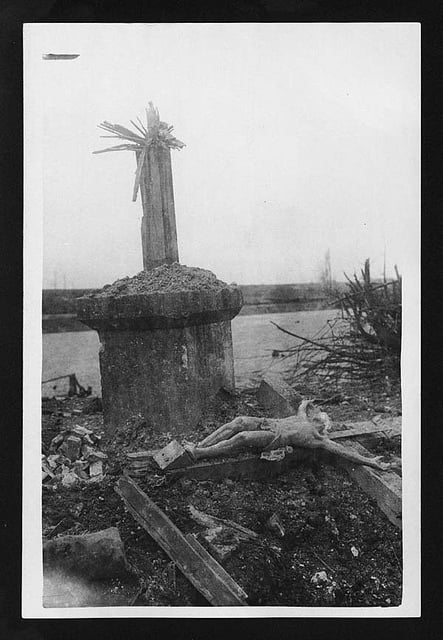

Certain states and races grasped the principle sooner than others, being marked out for early enlightenment by the accident of geographical position. In those not immediately affected, such as Britain, censorship on either side ruled out, as impossible for publication, the extent of the damage inflicted on allies, and the fact that it was not only in enemy countries that large masses of population, hunted out of cities by chemical warfare and the terror from above, had become nomadic and predatory. That, as the struggle grew fiercer, became, inevitably, the declared aim of the strategist; the exhaustion of the enemy by burdening him with a starving and nomadic population. War, once a matter of armies in the field, had resolved itself into an open and thorough-going effort to ruin enemy industry by setting his people on the run; to destroy enemy agriculture not only by incendiary devices — the so-called poison-fire — but by the secondary and even more potent agency of starving millions driven out to forage as they could…. The process, in the stilted phrase of the communique, was described as “displacement of population”; and displacement of population, not victory in the field, became the real military objective.

To the soldier, at least, it was evident very early in the struggle that the perfection of scientific destruction had entailed, of necessity, the indirect system of strategy associated with industrial warfare; displacement of population being no more than a natural development of the striker’s method of attacking a government by starving the non-combatant community. The aim of the scientific soldier, like that of the soldier of the past, was to cut his enemy’s communications, to intercept and hamper his supplies; and the obvious way to attain that end was by ruthless disorganization of industrial centres, by letting loose a famished industrial population to trample and devour his crops. Manufacturing districts, on either side, were rendered impossible to work in by making them impossible to live in; and from one crowded centre after another there streamed out squalid and panic-stricken herds, devouring the country as they fled. Seeking food, seeking refuge, turning this way or that; pursued by the terror overhead or imagining themselves pursued; and breaking, striving to separate, to make themselves small and invisible…. And, as air-fleets increased in strength and tactics were perfected — as one centre of industry after another went down and out — the process of disintegration was rapid. To the tentative and hesitating opening of the war had succeeded a fury of wide-spread destruction; and statesmen, rendered desperate by the sudden crumbling of their own people — the sudden lapse into primitive conditions — could hope for salvation only through a quicker process of “displacement” on the enemy side.

There were reasons, political and military, why the average British civilian, during the opening phases of the struggle, knew little of warfare beyond certain food restrictions, the news vouchsafed in the communiques and the regulation comments thereon; the enemy forces which might have brought home to him the meaning of the term “displacement” were occupied at first with other and nearer antagonists. Hence continental Europe — and not Europe alone — was spotted with ulcers of spreading devastation before displacement was practised in England. There had been stirrings of uneasiness from time to time — of uneasiness and almost of wonder that the weapon she was using with deadly effect had not been turned against herself; but at the actual moment of invasion there was something like public confidence in a speedy end to the struggle — and the principal public grievance was the shortage and high price of groceries.

Whatever he forgot and confused in after days — and there were stretches of time that remained with him only as a blur —Theodore remembered very clearly every detail and event of the night when disaster began. Young Hewlett’s voice as he announced disaster — and what he, Theodore, was doing when the boy rapped on the window. Not only what happened, but his mood when the interruption came and the causes of it; he had suffered an irritating day at the office, crossed swords with a self-important chief and been openly snubbed for his pains. As a result, his landlady’s evening grumble on the difficulties of war-time housekeeping seemed longer and less bearable than usual, and he was still out of tune with the world in general when he sat down to write to Phillida. He remembered phrases of the letter — never posted — wherein he worked off his irritation. “I got into trouble today through thinking of you when I was supposed to be occupied with indents. You are responsible, Blessed Girl, for several most horrible muckers, affecting the service of the country…. Your empty hospital don’t want you and my empty-headed boss don’t want me — oh, lady mine, if I could only make him happy by sacking myself and catching the next train to London!” … And so on and so on….

It was late, nearing midnight, when he finished his letter and, for want of other occupation, turned back to a half-read evening paper; the communiques were meagre, but there was a leading article pointing out the inevitable effect of displacement on the enemy’s resources and moral, and he waded through its comfortable optimism. As he laid aside the paper he realized how sleepy he was and rose yawning; he was on his way to the door, with intent to turn in, when the rapping on the window halted him. He pulled aside the blind and saw a face against the glass — pressed close, with a flattened white nose.

“Who’s that?” he asked, pushing up the window. It was Hewlett, one of his juniors at the office, out of breath with running and excitement.

“I say, Savage, come along out. There’s no end going on — fires, the whole sky’s red. They’ve come over at last and no mistake. Crashaw and I have been watching ’em and I thought you’d like to have a look. It’s worth seeing — we’re just along there, on the wall. Hurry up!”

The boy was dancing with eagerness to get back and Theodore had to run to keep up with him. He and Crashaw, Hewlett explained in gasps, had spent the evening in a billiard-room; it was on their way back to their diggings that they had noticed sudden lights in the sky — sort of flashes — and gone up on the wall to see better…. No, it wasn’t only searchlights — you could see them too — sudden flashes and the sky all red. Fires — to the south. It was the real thing, no doubt about that — and the only wonder was why they hadn’t come before…. At the head of the steps leading up to the wall were three or four figures with their heads all turned one way; and as Hewlett, mounting first, called ” Still going on?” another voice called back, “Rather!”

They stood on the broad, flat wall and watched — in a chill little wind. The skyline to the south and south-west was reddened with a glow that flickered and wavered spasmodically and, as Hewlett had said, there were flashes — the bursting of explosive or star-shells. Also there were moments when the reddened skyline throbbed suddenly in places, grew vividly golden and sent out long fiery streamers…. They guessed at direction and wondered how far off; the wind was blowing sharply from the north, towards the glow; hence it carried sound away from them and it was only now and then that they caught more than a mutter and rumble.

RADIUM AGE SCIENCE FICTION: “Radium Age” is HILOBROW’s name for the 1904–33 era, which saw the discovery of radioactivity, the revelation that matter itself is constantly in movement — a fitting metaphor for the first decades of the 20th century, during which old scientific, religious, political, and social certainties were shattered. This era also saw the publication of genre-shattering writing by Edgar Rice Burroughs, Sax Rohmer, E.E. “Doc” Smith, Jack London, Arthur Conan Doyle, Aldous Huxley, Olaf Stapledon, Karel Čapek, H.P. Lovecraft, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Yevgeny Zamyatin, Philip Gordon Wylie, and other pioneers of post-Verne/Wells, pre-Golden Age “science fiction.” More info here.

HILOBOOKS: The mission of HiLoBooks is to serialize novels on HiLobrow; and also, as of 2012, operating as an imprint of Richard Nash’s Cursor, to reissue Radium Age science fiction in beautiful new print editions. So far, we have published Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague, Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”), Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt, H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook, Edward Shanks’s The People of the Ruins, William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land, and J.D. Beresford’s Goslings. Forthcoming: E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man, Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage, and Muriel Jaeger’s The Man with Six Senses. For more information, visit the HiLoBooks homepage.

SERIALIZED BY HILOBOOKS: Richard Connell’s “The Most Dangerous Game” | Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague | Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”) | Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt | H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook | serialized between March and August 2012; Edward Shanks’ The People of the Ruins, serialized between May and September 2012; William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land, serialized between June and December 2012; J.D. Beresford’s Goslings, serialized between September 2012 and May 2013; and Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage, serialized between March and August 2013.