Early ’60s Horror (6)

By:

February 20, 2013

[Sixth in a series of posts by David Smay on horror movies of the early 1960s.]

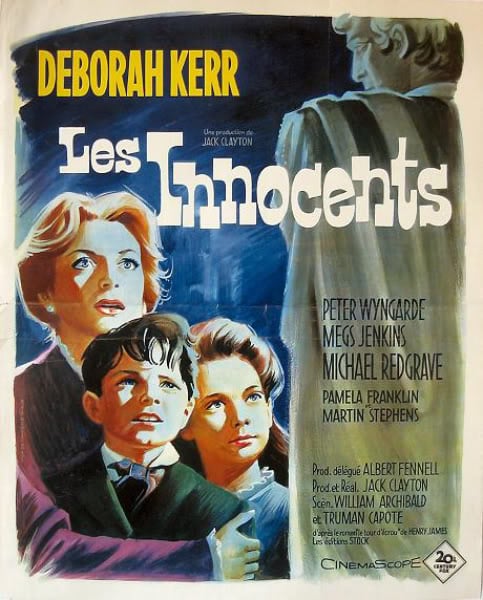

So much depends on Deborah Kerr’s face half in shadow. So much depends on Miss Jessel on the far side of the lake in the rain, watching. Jack Clayton’s 1961 film The Innocents is one of many adaptations of Henry James’s The Turn of the Screw but the only one that completely succeeds. The Innocents pairs with The Haunting (1963) in a perfect double feature of ghost stories, the definitive films of this Liminal Horror cycle of the early 1960s. Both movies hew closely to their female protagonists, neurotic women whose sexual repression drives the narrative. There is a direct literary lineage as Shirley Jackson’s novel The Haunting of Hill House derives from Turn of the Screw, just as Stephen King’s The Shining riffs on Hill House, the novels becoming successively less ambiguous about the existence of ghosts.

Time and James’s reputation have given The Turn of the Screw an air of literary respectability very different from its original reception as it was serialized in Collier’s over twelve issues. It caused the kind of excited moral panic granted those rare few works that burrow so deeply into an abscess of the psyche that they inspire revulsion, the sense that simply reading or viewing them is a violation. In this wise it keeps company with Jackson’s “The Lottery,” Psycho, and Blue Velvet. Reviews called it “distinctly repulsive,” “cruel” and “hopelessly evil.” It was also recognized as a master class in audience manipulation and other writers began cribbing from it immediately, most notably Joseph Conrad who couldn’t wait to try his hand at this unreliable narrator biz.

While adapting the book to film, Jack Clayton went to Harold Pinter for advice, and Pinter told him to lose the framing story in the original novella, and to avoid telling the story in flashback. There are innumerable structural issues with adapting Turn of the Screw, and each precarious because so much of the novella’s effect depends on limiting or controlling the point-of-view — an easy task on the page, but far more complicated on film.

The first solution then is the opening, as over a black screen we hear a child singing an eerie folk song, “O Willow Waly” (written for the film), a song about thwarted lovers who die tragically. It is (literally) one of the most haunting songs in film history; I would rate it with “Pretty Fly” in Night of the Hunter for establishing an unsettled, dreamlike state. The 20th Century Fox Logo flashes briefly to assure us that they haven’t forgotten to thread the projector, and we hear a woman’s tearful sobs. Then we see hands clasped and hear Miss Giddens’s (Kerr) too-fervent prayer for the safety of the children: “I only wanted to save the children, not destroy them.” Not something you want to hear from your new governess. It casts a dark sense of foreboding and unease before the plot gears into action.

When the new governess, Miss Giddens, arrives at the Bly estate all seems idyllic, a “paradise for children.” She’s been hired to look after two children orphaned and left in the care of their playboy uncle who can’t be bothered with parenting or country life so she’s been placed in absolute authority over the children and instructed not to bother him. There’s a recurring motif of white roses in the movie which begins with the one in the Uncle’s (Michael Redgrave) lapel. White roses typically signify innocence and purity, but they serve a double function here cuing us to Miss Giddens’s blossoming sexuality

She meets the housekeeper, Mrs. Grose, and her first charge, the seemingly angelic Flora. Meg Jenkins as Mrs. Grose provides a crucial fulcrum in the movie. She’s so real and grounded and – well, beyond grounded – earthy, that we take our cue from her on how to judge Miss Giddens’s increasingly erratic behavior. A curious element in the production is that all of the main players — save Ms. Kerr – are famous for exactly one other classic horror movie: Jenkins in Asylum, Martin Stephens in Village of the Damned, Pamela Franklin for The Legend of Hell House, Redgrave for Dead of Night, Peter Wyngaard for Burn Witch Burn.

It’s all too perfect, but paradise was designed to be corrupted, and slowly, hint by hint, Eden unravels. The young master, Miles, comes home from school, expelled in disgrace for his “injurious” effect on his classmates. And we learn through Mrs. Grose’s reluctant exposition of the previous governess, Miss Jessel, and her depraved relationship with the sadistic valet, Peter Quint. Though it is somewhat opaque to modern eyes, Quint and Jessel are coded in terms such that contemporaneous readers of James would have understood them to be child molesters. It is not just the example of their relationship that influences and damages the children. Quint died under mysterious circumstances, his head gashed in from some misadventure and crawling to his death on the front steps where Miles found him. Miss Jessel then drowned herself in the lake.

There is a delicious perversity in Truman Capote’s script, especially in his portrayals of the children Flora and Miles: the avid amorality of their laughter, Flora’s blunt, innocent appreciation of a spider devouring a butterfly, the outrageously sexualized moment when Miles plays at being the Lord of the Manor and dining with Miss Giddens where he reaches for her hand and then back-hands a rabbit shaped aspic causing it to jiggle like a slapped tit. These moments accrue between scenes where the children radiate lively charm and affection, so the balance tilts and wavers. They’re sinsister; they need protection.

As much as the production depends upon the performances that Jack Clayton delicately coaxes out of the children, it is Deborah Kerr’s performance that distinguishes The Innocents from all other adaptations. At age forty, Kerr – while still one of the most beautiful women in the world – is really too old to play the young governess who should be no more than twenty. But her age actually plays to her advantage as the character makes more sense as a spinster late escaping her father’s parsonage, sharpening her earnest naïveté, conviction, and repressed sexual appetite.

In much the same way that Hitchcock exploits James Stewart’s inherent likeability to get the viewer to follow him down a dark path in Vertigo, so Clayton draws on Kerr’s warmth and sensitivity to lure us into following Miss Giddens to the shocking end. And make no mistake, the ending of The Innocents is one of the most squirm-inducing scenes in the horror canon, just short of the bag flinching in Audition.

Through Kerr’s performance the film finds a way to evoke the novella’s slippery point-of-view, guiding us along that liminal state between the perceptible and the imagined, “the strange and sinister embroidered on the very type of the normal and easy” as James put it. But how to render James’s ripe and lustrous prose, the fine-stroked curlicues of his descending dependent clauses twining about the narrative like an Art Nouveau border?

The heightened, dreamy effect of James’s prose finds its filmic expression in Freddie Francis’s lush, painstakingly lit cinematography, bathing the estate in a summery glow, pricking out a wicked gleam in Quint’s eyes, enclosing Miss Giddens in dark tunnels of candlelight. It is one of the most beautifully shot black and white movies of the 1960a. Capote’s script further fills the background with macabre details, beetles scuttling out of statuary, which contorts and leers and looms toward us. While it’s common in haunted house stories to press down on the audience visually, claustrophobically, here Clayton achieves some of his best effects with distance and space on the estate, creating an agoraphobic sense of vulnerable exposure.

And so we descend with Miss Giddens, seeing what only she sees: the cruel, beautiful satyr-like face of Peter Quint in the glass, Miss Jessel waiting with dark intent across the distance, biding her time, the ghosts of Quint and Jessel come back to reclaim the children, to live through their corruption.

There is a contemporary ghost story trope that resolves the plot by resolving the ghost’s past trauma, by getting the ghost to let go of the past and leave the world. This trope is reassuring, and it feels apt because we’re so thoroughly inculcated with the therapeutic model. But ghost stories aren’t supposed to function like monster stories. Monster stories the classics of Universal Horror (Dracula, Frankenstein) are designed to restore order and the status quo by destroying the outlier/abhorrent thing that threatens the community. Ghost stories have a different effect; they’re disquieting. They insist that the past has a malign influence on the present that can never be resolved, that the darkness lingers at the periphery, in the distance, watching, waiting, reclaiming us.

MORE HORROR ON HILOBROW: Early ’60s Horror, a series by David Smay | Phone Horror, a series by Devin McKinney | Philip Stone’s Hat-Trick | Shocking Blocking: Candyman | Shocking Blocking: A Bucket of Blood | Kenneth Anger | Sax Rohmer | August Derleth | Edgar Ulmer | Vincent Price | Max von Sydow | Lon Chaney Sr. | James Whale | Wes Craven | Roman Polanski | Ed Wood | John Carpenter | George A. Romero | David Cronenberg | Roger Corman | Georges Franju | Shirley Jackson | Jacques Tourneur | Ray Bradbury | Edgar Allan Poe | Algernon Blackwood | H.P. Lovecraft | Clark Ashton Smith | Gaston Leroux |

OTHER HILOBROW SERIES: FITTING SHOES — famous literary footwear | POP ARCANA — spelunking weird culture | SHOCKING BLOCKING — cinematic blocking