1765-74: Original Romantics

By:

February 11, 2013

Men and women born from 1765-74 were in their teens and 20s during the Seventeen-Eighties (1785–94, not to be confused with the 1780s), and in their 20s and 30s during the Seventeen-Nineties (1795-1804, not to be confused with the 1790s). This demographic cohort, which grew up in the shadow of their immediate elders (the politics-, society-, and economics-obsessed Perfectibilists), constituted the first wave of Romanticism.

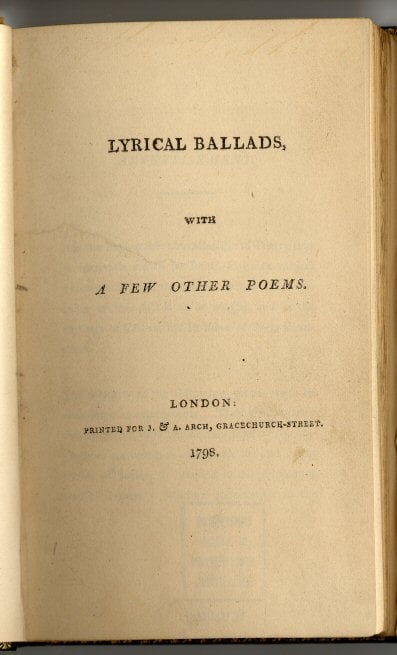

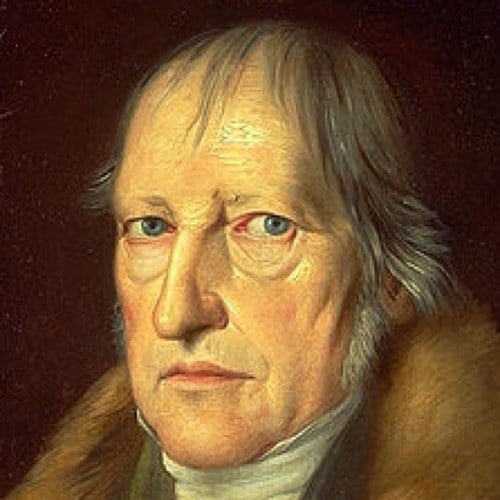

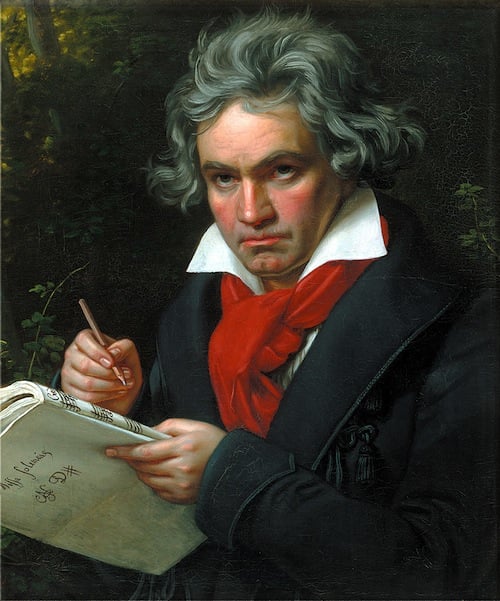

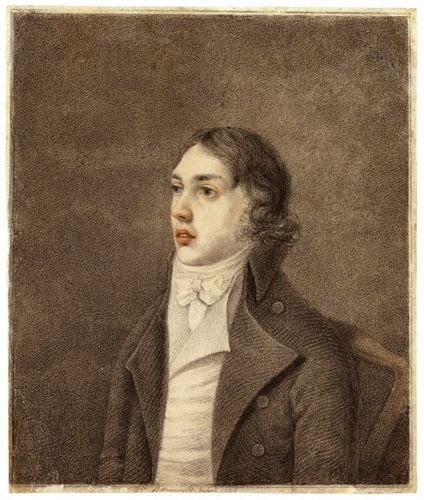

A counter-Enlightenment movement that prioritized culture and aesthetics over against politics and society and economics, and a passionate individual life over against everything else, Romanticism was spearheaded in Great Britain by the poets William Wordsworth (1770), Samuel Taylor Coleridge (1772), Robert Southey (1774), and Walter Scott (1771); and in Germany by August Wilhelm von Schlegel (1767) and Friedrich von Schlegel (1772), around whose journal the Athenäum gathered such pioneering Romantics as Novalis (1772) — who composed Hymns to the Night in 1798, the same year that Coleridge’s “The Rime of the Ancient Mariner” and Wordsworth’s “Lines Written a Few Miles from Tintern Abbey” appeared in the seminal collection Lyrical Ballads. German Romantics of this generation also include Wilhelm Heinrich Wackenroder (1773) and Ludwig Tieck (1773), not to mention Ludwig van Beethoven (1770), Friedrich Hölderlin (1770), and Friedrich von Schelling (1775: honorary Original Romantic). In France, meanwhile, François-René de Chateaubriand (1768) was the first — and for years, the only — Romantic; and Madame de Staël (1766) is credited with importing the movement from Germany. Finally, I should also mention the philosopher Hegel (1770), who influenced German Romanticism and was something of a counter-Enlightenment thinker… but who was not, himself, a Romantic.

This cultural generation is easily distinguished from its immediate elders, the Perfectibilists, and its immediate juniors, the Ironic Idealists. Romanticism’s first wave was born between 1765 and 1774. A handful of the Perfectibilists (e.g., Robert Burns, William Blake, Mary Wollstonecraft; and Friedrich Schiller) have often been described as pre-Romantics; the Ironic Idealists, meanwhile, are the first (but not last) post-Romantic generation.

A reminder of my 250-year generational periodization scheme:

1755-64: [Republican Generation] Perfectibilists

1765-74: [Republican, Compromise Generations] Original Romantics

1775-84: [Compromise Generation] Ironic Idealists

1785-94: [Compromise, Transcendental Generations] Original Prometheans

1795-1804: [Transcendental Generation] Monomaniacs

1805-14: [Transcendental Generation] Autotelics

1815-24: [Transcendental, Gilded Generations] Retrogressivists

1825-33: [Gilded Generation] Post-Romantics

1834-43: [Gilded Generation] Original Decadents

1844-53: [Progressive Generation] New Prometheans

1854-63: [Progressive, Missionary Generations] Plutonians

1864-73: [Missionary Generation] Anarcho-Symbolists

1874-83: [Missionary Generation] Psychonauts

1884-93: [Lost Generation] Modernists

1894-1903: [Lost, Greatest/GI Generations] Hardboileds

1904-13: [Greatest/GI Generation] Partisans

1914-23: [Greatest/GI Generation] New Gods

1924-33: [Silent Generation] Postmodernists

1934-43: [Silent Generation] Anti-Anti-Utopians

1944-53: [Boomers] Blank Generation

1954-63: [Boomers] OGXers

1964-73: [Generation X, Thirteenth Generation] Reconstructionists

1974-82: [Generations X, Y] Revivalists

1983-92: [Millennial Generation] Social Darwikians

1993-2002: [Millennials, Generation Z] TBA

LEARN MORE about this periodization scheme | READ ALL generational articles on HiLobrow.

NOTES ON ROMANTICISM

The Original Romantics were secular theologians (according to M.H. Abrams, who does not use the term “Original Romantics”); that is, they were dominated by a Biblically inspired eschatology which they transposed from heaven to earth. History is an upward spiral along which humankind travels towards an inevitable and predetermined end: a superior state of un-alienated oneness of, i.e., man with man, man with God, man with nature. The “kingdom of God” is reimagined as an earthly paradise — a utopia in which all opposites are reconciled. They consciously set out to transform not only the theory and practice of poetry (and all art), but the very way we perceive the world. While in their teens and 20s, the Original Romantics were enthusiastic about the French Revolution and its liberal ideals; and Hegel was enthusiastic about Napoleon — the “World Spirit… on horseback.” Later, they grew disillusioned about political revolutions.

Rejecting the Enlightenment insofar as it argued for the supremacy of reason, the Romantics elevated the imagination to a position as the supreme faculty of the mind, a dynamic creative power that unites reason and feeling and helps invent reality itself. Emphasis was placed on the importance of intuition, instincts, and feelings; Wordsworth defined good poetry as “the spontaneous overflow of powerful feelings.” The artist became, for the first time, a heroic figure. Also unlike Enlightenment’s rationalist view of nature and the universe, the Romantics viewed nature as an organically unified whole — and as such, a refuge from the artificial constructs of civilization. Style-wise, the Romantics preferred boldness over neoclassicism’s insistence upon restraint; maximum suggestiveness over the neoclassical ideal of clarity; and free experimentation instead of following rules. In their pursuit of authenticity, they turned for symbolism to folk legends and ballads, to contemporary country folk and to children.

NOTES ON AUTHENTICITY

As I wrote in Hermenaut, back in 1999, the phenomenon of fake authenticity begins with Hegel.

Hegel’s Phenomenology of Spirit (1807) is the most important text in the pre-history of existential authenticity. In it, Hegel attacks the bourgeois “honest man,” whose self-seriousness and sincerity exemplifies a passive submission to a received social ethos. Hegel’s romantic portrait of the anti-hero of authenticity was deeply influenced by Rameau’s Nephew, a dialogue discovered after Diderot’s death in that philosophe’s papers. In it, Diderot appears as “Myself,” an honest bourgeois philosopher; and the Nephew of the title is his opposite number, a poverty-stricken musician who earns his keep in the homes of wealthy patrons by being himself: an insincere, buffoonish parasite. Believing that history can be seen as a progress toward a truly self-determining freedom, Hegel used the term base to mean “alienated from and antagonistic towards the prevailing ethos of society” — and applied it to the agent of this kind of freedom. Likewise, he turned noble into a pejorative, using it to mean “overly identified, internally and externally, with the prevailing ethos.” The Nephew, Hegel, decided, was a prime example of the courageously base man — a disintegrated, alienated, distraught consciousness seeking a self-determining freedom. He pours out his irony on the bourgeoisie, mocking their earnestness, and exposing the constructed nature of their taken-for-granted ideas about truth, meaning, and morality. The anti-hero of authenticity spends his days, Hegel insists approvingly, “in universal talk and in deprecatory judgment which rends and tears everything.”

Here’s my two cents: Try reading Rameau’s Nephew after you’ve just read Thomas Frank’s The Conquest of Cool (1997). It becomes immediately apparent that the Nephew rejects the prevailing ethos not in order to follow his own pathos (i.e. like a real anti-hero of authenticity), but because, as he puts it, “with the aid of vices natural to me [I have made myself] agreeable to the tastes of my patrons.” The solid bourgeois Diderot finds the Nephew’s company enjoyable not because he’s been revolutionized by this abject outsider, but “because [his] character stands out from the rest and breaks that tedious uniformity which our education, our social conventions, and our customary good manners have brought about.” The Nephew is a romantic rebel-with-a-small-“r,” through whom solid citizens can vicariously fantasize about surpassing the limits of their own freedom. The Nephew — as theorized by Hegel, anyway, because who knows what Diderot intended the dialogue to mean — is really the hip face of capitalism, an architect of consumer dissatisfaction and of perpetual obsolescence. These phenomena, I’d argue, are an unintended consequence of Romanticism.

Meet the Original Romantics.

HONORARY ORIGINAL ROMANTICS (born 1764): Dorothea von Schlegel (German novelist, important figure in early German romanticism; oldest daughter of the philosopher Moses Mendelssohn, the greatest Jewish philosopher of the Enlightenment; left her husband for Friedrich von Schlegel; hosted a salon frequented by Tieck, Schelling, the Schlegel brothers, and Novalis; contributed to the Schlegels’ journal Athenäum; friend of Germaine de Staël)

1765 (cuspers): Pope Gregory XVI (strongly conservative and traditionalist, he opposed democratic and modernising reforms in the Papal States and throughout Europe, seeing them as fronts for revolutionary leftism, and he sought to strengthen the religious and political authority of the papacy); Franz Xaver von Baader (German theologian, mystic, engineer; influenced Hegel); King William IV (King of England, uncle of Queen Victoria); Sir James Ivory (mathematician); Nicéphore Niépce (inventor, photography); James Smithson (chemist, funded the Smithsonian). HONORARY PERFECTIBILISTS: Robert Fulton (inventor), Eli Whitney (inventor).

1766: Madame (Germaine) de Staël (married the Swedish diplomat to France; political activist; salon intellectual; best-selling author of two autobiographical feminist novels; coined the word “Romanticism”; brought German literary culture to the rest of Europe through her book De l’Allemagne; socialized with Goethe, Schiller, Coleridge, Byron, Benjamin Constant), Thomas Malthus (counter-Enlightenment economist, Essay on the Principle of Population), John Dalton (early proponent of atomic theory), Charles Macintosh (invented the raincoat), William Hyde Wollaston (chemist, discovered palladium, rhodium).

1767: August Wilhelm von Schlegel (German poet, translator, critic, and a foremost leader of German Romanticism; with his brother Friedrich he published the Athenaeum, the organ of the Romantic school; his translations of Shakespeare made the English dramatist’s works into German classics), John Quincy Adams (6th US president), Andrew Jackson (7th US president), Wilhelm von Humboldt (scholar), Black Hawk (led Indian uprisings), Benjamin Constant (French political thinker), Marie Edgeworth (author, Castle Rackrent), Jean-Lambert Tallien (French revolutionary).

1768: François-René de Chateaubriand (considered the founder of Romanticism in French literature), Friedrich Schleiermacher (German theologian and philosopher known for his impressive attempt to reconcile the criticisms of the Enlightenment with traditional Protestant orthodoxy; his work also forms part of the foundation of the modern field of hermeneutics; contributed to the Schlegels’ journal Athenäum), Jean Baptiste Joseph Fourier (mathematician), Dolley Madison (wife of President James Madison), Samuel Slater (known as Father of the American Industrial Revolution).

1769: Napoleon Bonaparte (emperor of France; for Byron, Napoleon in exile was the epitome of the Romantic hero, the persecuted, lonely and flawed genius), Arthur Wellesley (1st Duke of Wellington, defeated Napoleon at Waterloo), August Ferdinand Bernhardi (linguist, early German romantic, contributed to the Schlegels’ journal Athenäum), De Witt Clinton (twice governor of New York), Georges Cuvier (zoologist).

1770: Ludwig van Beethoven (German composer), Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel (influential philosopher), William Wordsworth (key English romantic poet), William Clark (Lewis and Clark expedition, Friedrich Hölderlin (German Romantic poet, important thinker in the development of German Idealism), James Hogg (poet).

1771: Sir Walter Scott (author, Ivanhoe), Robert Owen (activist, socialist, utopian: founder of the Cooperative Movement), Mungo Park (Scottish explorer), Éleuthère Irénée du Pont (founder of DuPont).

1772: Samuel Taylor Coleridge (key English romantic poet), Friedrich von Schlegel (founder of the German Romantic movement), Novalis (Georg Philipp Friedrich Freiherr von Hardenberg; author and philosopher of early German Romanticism; developed the fragment as a literary form of art; his unfinished novel Heinrich von Ofterdingen was published posthumously), Charles Fourier (Socialist utopian philosopher), Josiah Quincy (president of Harvard, 1829-45), David Ricardo (Economist).

1773: Ludwig Tieck (German novelist, a co-founder of German Romanticism), Wilhelm Heinrich Wackenroder (jurist and writer; a co-founder of German Romanticism), Nathaniel Bowditch (astronomer, navigator), Robert Brown (botanist, Brownian motion) George Cayley (father of aeronautics), William Henry Harrison (9th US President), Sally Hemings (Thomas Jefferson’s slave mistress), Klemens Wenzel von Metternich (influential Austrian ambassador), Thomas Young (physicist, Wave Theory of Light).

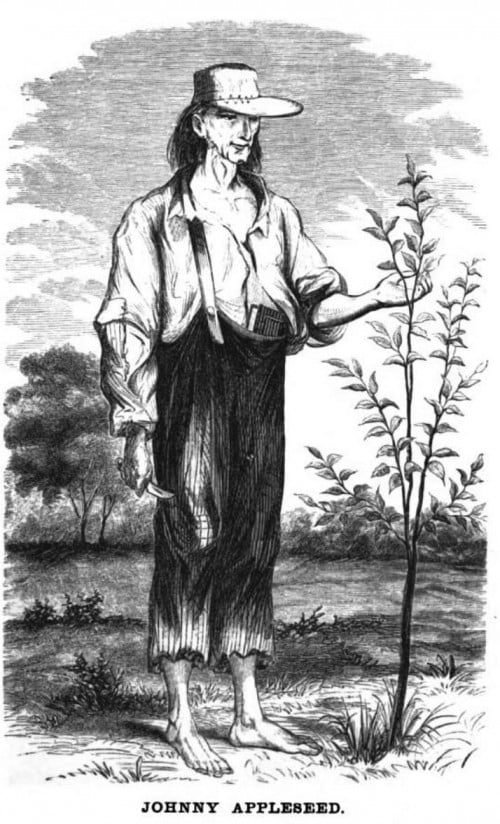

1774 (cuspers): Johnny Appleseed (itinerant preacher, apple tree distributor), Meriwether Lewis (Lewis and Clark expedition), Robert Southey (English romantic poet, utopian), Caspar David Friedrich (German Romantic painter), James Mill (historian and economist, member of a group of “philosophic radicals,” father of John Stuart Mill), Francis Baily (astronomer), Samuel Butler (scholar). HONORARY IRONIC IDEALISTS: Louis-Philippe (king of France, 1830-48), Abner Kneeland (American freethinker).

HONORARY ORIGINAL ROMANTICS (born 1775): Friedrich Wilhelm Joseph von Schelling (Philosopher, Naturphilosophie), J.M.W. Turner (Painter, Romanticist English landscape painter).

ADVENTURE WRITERS: Walter Scott (Top 200: Waverley, Ivanhoe)