Resistant Objects

By:

January 29, 2013

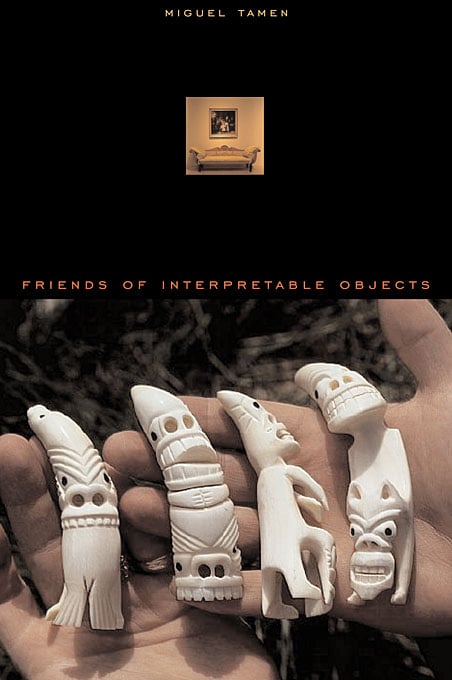

I’ve been nursing a gentle obsession with a quartet of figurines I first saw on the cover of Miguel Tamen’s book Friends of Interpretable Objects (Harvard, 2004): resting in a pair of open hands, a row of anthropozoic beings, bone-white, toothy, and vital. Their heads are cocked at mad angles, with leering eyes and rabid smiles that bespeak a secret, conspiratorial sociability. Undeniably charismatic, they exude a cool glow, evoking the long Arctic night and the estranging cold. And yet they’re also tiny, antic, and personable, their features smooth and soft enough to enfold cozily in the palm.

In his book, Tamen argues that objects — art objects in the first instance, but also the many things upon which our fascination fixes, such as shells, stones, stars, milk bottles, leaves, and lamps — take up power and life with us as we incorporate them into “societies of friends,” transforming our desire for things into engagement with, and advocacy for, the world of things. The figurines on the cover of Tamen’s book present an admirable picture of such a society of friends, and yet they were never mentioned in the text; most likely, the image was chosen by the designer, seized on as a quartet of seemingly interpretable objects, without much attention to items specified in the manuscript. On the back cover, however, there was a bit of metadata: a caption, which described the objects as “devil figures” with a provenance of Tuktoyaktuk in Canada’s Northwest Territories, and which said that they were “carved from the teeth of a blue whale.”

I haven’t been to the Northwest Territories, and I have never seen a blue whale, but I do know a couple of things: they do not range as far north as Tuktoyaktuk, and they do not have teeth. Tuktoyaktuk, a remote village on the Arctic Ocean, achieved some renown in recent years as the northern terminus of one of the wintertime highways plied in the reality TV series “Ice Road Truckers.” The objects on the cover of Tamen’s book were likely made from the teeth of beaked whales — perhaps belugas, traditionally hunted by the Inuvialuit people who live at Tuktoyaktuk in Canada’s Northwest Territories. The blue whale’s mouth, for its part, is toothless, and filled with baleen — a light, tough, and flexible material that serves to filter meals of plankton from seawater (the creature below is a right whale, which also has baleen).

Further search turned up a link to the original image up at the image bank Corbis, where the error is reproduced. A person holds devil figures carved from teeth of a blue whale, Tuktoyaktuk, Northwest Territories, Canada, reads the caption there. The photo was taken by Lowell George for Corbis on August 1, 1980; its ID number is LG002968.

While the caption may err in identifying the carvings as the teeth of a blue whale, it’s not too far off in calling them devils. The little ivory characters are examples of tupilaq, a genre of carved critter widespread among the Inuit and other peoples of the far north. Aboriginal tupilaq were evil spirits called into being by a shaman for the purpose of making mischief, carrying curses to rivals and enemies. Made from bone and fur and other materials, the tupilaq were powerful magic — and dangerous, for if discovered, their powers would turn back on their wielders unless an immediate public confession were made. Secrecy and darkness were the native habitat of the tupilaq; they lose their power when exposed to the sociable light.

I’m not interested in scolding Corbis or Lowell George, however, whose photo marvelously evokes the capricious spirit of the tupilaq for one who never has been so far north. For now, I’m interested to note the ways in which collectible objects want to weave shadows and ambiguities around themselves. The light-skinned hands holding the tupilaq in the photo manifest some degree of control over the carvings, but of a kind that never can be total; the object arrives replete with connections, and hoards its most intimate gestures and relations in some unreachable treasure-house. The collected object is a kind of latch turning on inaccessible and incommensurable worlds of sense and event, an irredeemable record of acts and things, a tissue of phenomenal dark matter twisted intimately into time’s obliterative machinery. The tupilaq, after all, were the teeth of an animal whose warm blood surged against tide and ice; teeth that dragged something bleeding into the black, and tore bubbles in ribbons through holes in the toiling ice; teeth that thrummed, their ivory timbre in tune with whalesong ringing in submarine canyons and out across ice-hung plains of shingle. Torn from reek on the bloodsoaked shore; these teeth were plucked and cleaned and polished, carved finally into devils breeding unluck on a neighbor’s lodge, his wives, his weapons. Every gesture, every practice of craft and magic and the secret haunts of commerce, took them further into something and farther away.

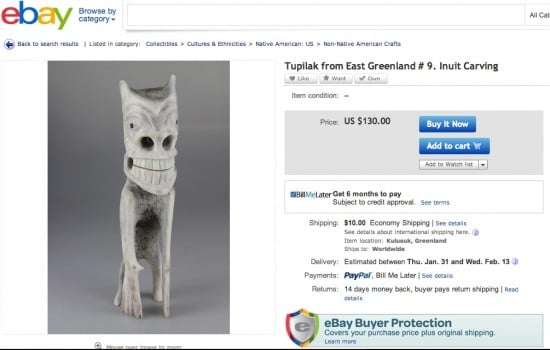

Nor quite this, in the end — for here’s another twist to the tupilaq’s tale: the charismatic ivory carvings are a product of the mid twentieth century; the aboriginal tupilaq was a shamanic object made of perishable (and sometimes unspeakable) matter, contrived to call the spirit forth. The carvings were done at the request of white traders and travelers, who wished to see what the “real” devils, the ones evoked by the dirty, crumbling effigies, actually looked like. They’ve long been popular items in the Inuit art trade, where they fetch their makers a tidy price — commerce weaving another layer of secrecy behind which the tupilaq themselves dance and hide.

What I’m trying to do is understand how things come to take their place — especially in museums and collections — as embodiments of knowledge, artifacts out of time and nature, and objects provoking curiosity and wonder, how they become objectified. And just as much as Foucault long ago pointed out, neither the natural nor the human sciences exist until “nature” and “the human” take their modern form as such, I’m eager to imagine a science that employs enough modesty to realize that the objects of its interest do not take their sole, true, or final form beneath its gaze. Even under the light of science, objects withdraw their auras, that dark matter reaching back into deep time; and when the museums are in ruins, they will expose new banners to unfolding time. I think Tamen would agree with me here — the tupilaq are players in a luminous, long-durée ecology in which paintings and pelts, sculptures and scarab beetles, clay pots and crania take equal part.