Goslings (14)

By:

December 7, 2012

HILOBROW is pleased to present the fourteenth installment of our serialization of J.D. Beresford’s Goslings (also known as A World of Women). New installments will appear each Friday for 23 weeks.

When a plague kills off most of England’s male population, the proper bourgeois Mr. Gosling abandons his family for a life of lechery. His daughters — who have never been permitted to learn self-reliance — in turn escape London for the countryside, where they find meaningful roles in a female-dominated agricultural commune. That is, until the Goslings’ idyll is threatened by their elders’ prejudices about free love!

J.D. Beresford’s friend the poet and novelist Walter de la Mare consulted on Goslings, which was first published in 1913. In May 2013, HiLoBooks will publish a beautiful new edition of the book. “A fantastic commentary upon life,” wrote W.L. George in The Bookman (1914). “Mr. Beresford possesses the rare gift of divination,” wrote The Living Age (1916). “It is piece of the most vivid imaginative realism, as well as a challenge to our vaunted civilization.” “At once a postapocalyptic adventure, a comedy of manners, and a tract on sexual and social equality, Goslings is by turns funny, horrifying, and politically stirring,” says Benjamin Kunkel in a blurb for HiLoBooks. “Most remarkable of all may be that it has not yet been recognized as a classic.”

SUBSCRIBE to HILOBROW’s serialized fiction via RSS.

ALL EXCERPTS: 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23

4

Firm and somewhat clumsy steps were heard in the passage, the door was pushed roughly open, banging back against the black oak chair which was set behind it, and Aunt May entered carrying a large tray.

“Here’s your dinner, Fanny,” she said. “We’ve done earlier to-night, in spite of interruptions.” She bustled over to the little table in the window, pushed back the Bible and photograph with the edge of the tray until she could release one hand, and then, having driven the tray into a position of safety, moved Bible and photograph to the centre table.

There was something protestingly vigorous about her movements, as though she endeavoured to combat by noise and energy the impoverished vitality of that emasculate room.

“Now, you three!” she went on. “You had better come out into the kitchen and take your things off and wash.”

As the Goslings rose, Mrs Pollard turned to them and stretched out to each in turn her delicate white hand. “There is only one Comforter,” she said. “Put your trust in Him.”

Mrs Gosling gulped, and Blanche and Millie looked as they used to look when they attended the Bible-classes held by the vicar’s wife.

Blanche gave a shiver of relief as they came out into the passage. Her mind was suddenly filled by the astounding thought that everything was not different….

Supper was laid on the kitchen table cold chicken, potatoes and cabbage, stewed plums and cream, and warm, new milk in a jug; no bread, no salt, and no pepper.

As the three Goslings washed at the scullery sink they chattered freely. They felt pleasure at release from some cold, draining influence; they felt as if they had come out of church after some long, dull service, into the air and sunlight.

“I’m sure she’s a very ’oly lady,” was Mrs Gosling’s final summary.

Blanche shivered again. “Oh! freezing!” was her enigmatic reply.

Millie said it gave her “the creeps.”

They were a party of seven at supper — the meal was referred to as “supper,” although to Mrs Pollard it had been dignified by the name of “dinner”— including two young women whom the Goslings had not hitherto seen; strong, brown-faced girls, who spoke with a country accent. They had something still of the manner of servants, but they were treated as equals both by Allie and Aunt May.

There was little conversation during the meal, however, for all of them were too intent on the business in hand. To the Goslings that meal was, indeed, a banquet.

When they had all finished, Aunt May rose at once. “Thank Heaven for daylight,” she remarked; “but we must set our brains to work to invent some light for the winter. We haven’t a candle or a drop of oil left,” she went on, addressing the Goslings, “and for the past five weeks we have had to bustle to get everything done before sunset, I can tell you. Last night we couldn’t wash up after supper.”

“We know,” replied Blanche.

Aunt May nodded. “We all know,” she said. “Now, you three girls, get busy!” And Allie and the two brown-faced young women rose a little wearily.

“I’m getting an old woman,” remarked Aunt May, “and I’m allowed certain privileges, chief of them that I don’t work after supper.” She paused and looked keenly at the three Goslings. “Which of you three is in command?” she asked.

“Well, it seems as if my eldest, Blanche, that is, ’as sort o’ taken the lead the past few days,” began Mrs Gosling.

“Ah! I thought so,” said Aunt May. “Well, now, Blanche, you’d better come out into the garden and have a talk with me, and we’ll decide what you had better do. If your mother and sister would like to go to bed, Allie will show them where they can sleep.”

She moved away in the direction of the garden and Blanche followed her.

XIV

AUNT MAY

The sun had set, but as yet the daylight was scarcely faded. Under the trees the fowls muttered in subdued duckings, and occasionally one of them would flutter up into the lower branches with a squawk of effort and then settle herself with a great fluttering and swelling of feathers, and all the suggestion of a fussy matron preparing for the night — preparing only, for these early roosters sat open-eyed and watchful, as if they knew that there was no chance of sleep for them until every member of that careless crowd below had found its appointed place in the dormitory.

“We put ’em inside in the winter,” remarked Aunt May, as she and Blanche paused, “but they prefer the trees. We haven’t any foxes here, but I’ve noticed that the wild things seem to be coming back.”

Blanche nodded. She was thinking how much there was to learn concerning those matters which appertained to the production of food.

“They’re rather a poor lot,” Aunt May continued, “but they have to forage for themselves, except for the few bits of vegetable and such things we can spare them. We’ve no corn or flour or meal of any kind for ourselves yet. But a farmer’s wife about a mile from here has got a few acres of wheat and barley coming on, and we shall help her to harvest and take our share later. We shall be rich then,” she added, with a smile.

“I’m town-bred, you know,” said Blanche. “We’ve got an awful lot to learn, Millie and me.”

“You’ll learn quickly enough,” was the answer. “You’ll have to.”

“I suppose,” returned Blanche.

At the end of the orchard through which they had been passing they came to a knoll, crowned by a great elm. Round the trunk of the elm a rough seat had been fixed, and here Aunt May sat down with a sigh of relief.

“It’s a blessed thing to earn your own bread day by day,” she said. “It’s a beautiful thing to live near the earth and feel physically tired at night. It’s delightful to be primitive and agricultural, and I love it. But I have a civilized vice, Blanche. I have a store of cigarettes I stole from a shop in Harrow, and every night when it’s fine I come out here after supper and smoke three; and when it’s wet I smoke ’em in my own bedroom, and I dream. But tonight I’m going to talk to you, because you want help.”

She produced a cigarette case and matches from a side pocket of her jacket, lit a cigarette, inhaled the smoke with a long gasp of intensest enjoyment, and then said: “Men weren’t fools, my dear; they had pockets in their coats.”

“Yes?” said Blanche. She felt puzzled and a little awkward. She knew that this woman was a friend, but the girl’s town-bred, objective mind was critical and embarrassed.

“Do you smoke?” asked Aunt May. “I can spare you a cigarette, though I know the time must come when there won’t be any more. Still, it’s a long way off yet. Bless the clever man who invented air-tight tins!”

“No, I don’t smoke, thanks,” replied Blanche, conventionally; and, try as she would, she could not keep some hint of stiffness out of her voice. Modern manners take a long time to influence suburban homes of the Wisteria Grove type.

“Ah! well, you miss a lot!” said Aunt May; “but you’re better without it, especially now, when tobacco isn’t easy to get, and will soon be impossible.”

“But do you think,” asked Blanche, drawing her eyebrows together, “that this sort of thing is going on always?”

“I dare say. Don’t ask me, my dear; the problem’s beyond me. What we poor women have got to do is to keep ourselves alive in the meantime. And that’s what we’ve come out here to talk about. What about your mother and you two girls? Where are you going? And what are you proposing to do?”

“I don’t know,” said Blanche. “I—I’ve been trying to think.”

“Good!” remarked Aunt May. “I believe you’ll do. I’m doubtful about your sister.”

“We’ll have to work on a farm, I suppose.”

“It’s the only way to live.”

“Only where?”

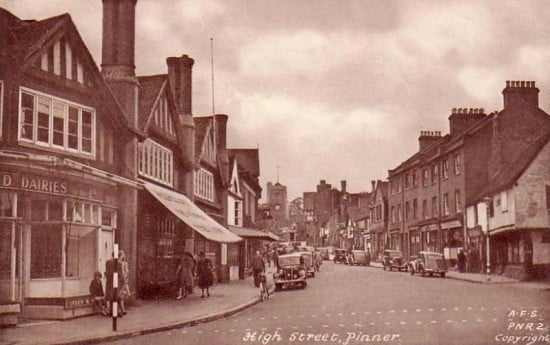

“That’s what I’ve been trying to worry out,” said Aunt May. “We do get news here, of a sort. Our girls work in Mrs Jordan’s fields, and meet girls and women who come from Pinner, and the Pinner people hear news from Northwood, and the Northwood people from somewhere else; and so we get into touch with half a county. But, coming to your affairs; you see, we here are just the innermost circle. Most of the women who came from London missed this place and passed us by, thanks be!… Now, that poor unfortunate Miss Grant, down the road, had to defend herself with weapons. Fortunately she’s strong.”

“Is Miss Grant the awful woman with the broomstick?” asked Blanche.

“She’s not really awful, my dear,” said Aunt May, smiling; “she’s a very good sort. A little rough in her manners, perhaps, and quite mad about the uselessness of the creatures we used to know as men, but a fine, generous, unselfish woman, if she does boast of her three murders. Did she tell you that, by the way?”

Blanche nodded.

“She would, of course; and I believe it’s true; but her theory was to defend her own people. She said they’d all have died if she hadn’t. I’m not sure about the ethic, but I know dear old Sally Grant meant well. However, I’m wandering —I often do when I talk like this. The point was that just this little circle here, close to London, is very thickly populated, and there’s precious little food ready to be got any way; but you’ll have to pass through the country beyond Pinner before you’ll find a place where they’ll give you work and keep you. There’s a surplus in the next ring, I gather, too much labour and too little to grow. You’ll have to push out into the Chilterns, out to Amersham at the nearest. It’s all on the main road, of course, which is bad in a general way, because that’s the road they all took. But I think if you’ll cut across towards Wycombe you might, perhaps, find a place of some sort, though whether they’ll feed your mother free gratis I can’t say. Women are of all sorts, but this plague hasn’t made ’em more friendly to one another, or perhaps it is we notice it more, and the worst of the lot are the farmers’ wives and daughters who’ve got the land. They get turned out, though, sometimes. We hear about it. The London women have made raids; only, you see, the poor dears don’t know what to do with the land when they get it, so they have to keep the few who do know to teach ’em — when they’re sensible enough — the raiders, I mean. They aren’t always.”

“It’ll be an adventure,” remarked Blanche.

Aunt May threw away the very short end of her second cigarette and lighted her third. “Adventure will do you good,” she said.

It was nearly dark under the elm. The things of the night were coming out. Occasionally a cockchafer would go humming past them, the bats were flitting swiftly and silently about the orchard, and presently an owl swept by in one great stride of soundless flight.

“How they are all coming back!” murmured Aunt May. “All the wild things. I never saw an owl here before this year.”

“I should be frightened if you weren’t here,” said Blanche.

“Nothing to be frightened of, yet.”

“Yet?”

“In a few years’ time, perhaps. I don’t know. We killed a wild cat who came after the chickens a few days ago. The cats have gone back already, and the dogs aren’t so respectful as they used to be. The dogs’ll interbreed, I suppose, and evolve a common form — strike some kind of average in a beast which will be somewhere near the ancestral type, smaller, probably, I don’t know. It’s a wonderful world, and very interesting. I could almost wish man wouldn’t return for twenty years or so — just to see how much of his handiwork Nature could undo in the interval. I often think about it out here in the evenings.”

“I wish I knew more about it,” said Blanche timidly. “Are there any books, do you know, that —”

“You won’t want books, my dear. Keep your eyes open and think.”

They lapsed into silence again. The third cigarette was finished, but Aunt May gave no indication of a desire to get back to the house, and Blanche’s mind was so excited with all the new ideas which were pouring in upon her that she had forgotten her tiredness.

“It’s awfully interesting,” she said at last. “It’s all so different. Mother and Millie hate it, and they’d like all the old things back; but I don’t think I would.”

“You’re all right. You’ll do,” replied her companion. “You’re one of the new sort, though you might never have found it out if it hadn’t been for the plague. Now, your sister will do one of two things, in my opinion; either she’ll stop in some place where there’s a man — there’s one at Wycombe, by the way — and have children, or she’ll turn religious.”

Blanche was about to ask a question, but Aunt May stopped her. “Never mind about the man, my dear,” she said. “You’ll learn quickly enough. It’s like Heaven now, you see — no marrying or giving in marriage. With one man to every thousand women or so, what can you expect? It’s no good kicking against it. It’s got to be. That’s where Fanny —” She broke off suddenly, with a little snort of impatience. “I think tonight’s an exception,” she went on. “I like talking to you, and one simply can’t talk to Allie yet, so just tonight I’ll have one more.” She took out her cigarette case with a touch of impatience.

It was dark under the elm now, and she had to hold up her cigarette case close to her face in order to see the contents. “Two more,” she announced. “It’s a festival, and for once I can speak my mind to some one. An imprudence, perhaps, like this habit of smoking, but I shall probably never see you again, and I’m sure you won’t tell.”

“Oh, no!” interposed Blanche eagerly.

“You’re not tired? You don’t want to go to bed?”

“Not a bit. I love being out here.”

“I can’t see you, but I know you’re speaking the truth,” said Aunt May, after a pause. “In the darkness and silence of the night I will make a confession. I look weather-worn and fifty, I know, but I feel absurdly romantic, only there’s no man in this case. I used to write novels, my dear — an absurd thing for any spinster to do, but they paid, and I’ve got the itch for self-expression. That’s the one outlet I miss in this new world of ours. Sally Grant and I can’t agree, and, in any case, she wants to do all the talking. And sometimes I’m idiot enough to go on writing little bits even now when I have become a capable, practical woman with at least four lives dependent upon me. Well, it shows, anyhow, that we writing women weren’t all fools….” She hung on that for a moment or two, and then continued.

“Are you religious?”

“I don’t know I suppose so. We always went to Church at home,” said Blanche. “I thought every one was, almost. Not quite like Mrs Pollard, of course.”

“Oh, well!” said Aunt May. “There’s no harm and a lot of good in being religious, if you go about it in the right way. I don’t want to change your opinions, my dear. It’s just a question to me of the right way. And I can’t see that Fanny’s way is right. Here we are, and we’ve got to make the best of it; and to my mind that means facing life, and not shutting yourself into one room with a Bible and spending half your time on your knees. Fanny never was good for much. She brought up Alfred — my nephew, you know — with only one idea, and she stuffed him so full of holiness that the English Church couldn’t hold him, and he had to work some of it off by going over to Rome. He thought he’d have better chances of saintship there. He was a poor, pale thing, anyway. Of course, that was anathema to Fanny. She might have forgiven him for committing a murder, but to become a Roman Catholic —! Oh, Lord! She’s been praying for him ever since. And, my dear, what difference can it make? Alfred’s apostasy, I mean. Do you think it matters what particular form of worship or pettifogging details of belief you adopt? Why can’t the Churches take each other for granted, and be generous enough to suppose that all roads lead to Heaven, which is, according to all accounts, a much better place than Rome? But, oh! above all, if you have a religion, do be practical! Come out and do your work, instead of sighing and psalm-singing, and wearying dumb Heaven with fulsome praise and lamentations of your unworthiness, as if you were trying to propitiate a rich customer!

“There, my dear, I won’t say any more. My last cigarette’s done, and wasted, because I was too excited to enjoy it. I know I’ve been disloyal; but it’s my temperament. I could slap Fanny sometimes. And she shan’t have Allie…. It’s the night that has affected me. To-morrow I shall be just as practical as ever, and you’ll forget that you’ve seen this side of me. Come along. We must go to bed.”

“This is the greatest night of my life,” thought Blanche as they walked back in silence to the house.

Even when she was in bed, she did not go to sleep at once. She lay and listened to the heavy breathing of her mother and Millie, and she wondered. Everything, indeed, was different, but everybody was just the same, only, in some curious way, individualities seemed more pronounced.

Could it be that everybody was more natural, that there was less restraint?

Blanche was not introspective. She did not test the theory on herself. She thought of the women she had met that day, and of her mother and Millie.

She fell asleep, determined to be more like Aunt May.

RADIUM AGE SCIENCE FICTION: “Radium Age” is HILOBROW’s name for the 1904–33 era, which saw the discovery of radioactivity, the revelation that matter itself is constantly in movement — a fitting metaphor for the first decades of the 20th century, during which old scientific, religious, political, and social certainties were shattered. This era also saw the publication of genre-shattering writing by Edgar Rice Burroughs, Sax Rohmer, E.E. “Doc” Smith, Jack London, Arthur Conan Doyle, Aldous Huxley, Olaf Stapledon, Karel Čapek, H.P. Lovecraft, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Yevgeny Zamyatin, Philip Gordon Wylie, and other pioneers of post-Verne/Wells, pre-Golden Age “science fiction.” More info here.

HILOBOOKS: The mission of HiLoBooks is to serialize novels on HiLobrow; and also, as of 2012, operating as an imprint of Richard Nash’s Cursor, to reissue Radium Age science fiction in beautiful new print editions. So far, we have published Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague, Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”), Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt, H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook, Edward Shanks’s The People of the Ruins, William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land, and J.D. Beresford’s Goslings. Forthcoming: E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man, Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage, and Muriel Jaeger’s The Man with Six Senses. For more information, visit the HiLoBooks homepage.

SERIALIZED BY HILOBOOKS: Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague | Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”) | Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt | H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook | Edward Shanks’ The People of the Ruins | William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land | J.D. Beresford’s Goslings | E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man | Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage | Muriel Jaeger’s The Man With Six Senses | Jack London’s “The Red One” | Philip Francis Nowlan’s Armageddon 2419 A.D. | Homer Eon Flint’s The Devolutionist | W.E.B. DuBois’s “The Comet” | Edgar Rice Burroughs’s The Moon Men | Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s Herland | Sax Rohmer’s “The Zayat Kiss” | Eimar O’Duffy’s King Goshawk and the Birds | Frances Hodgson Burnett’s The Lost Prince | Morley Roberts’s The Fugitives | Helen MacInnes’s The Unconquerable | Geoffrey Household’s Watcher in the Shadows | William Haggard’s The High Wire | Hammond Innes’s Air Bridge | James Branch Cabell’s Jurgen | John Buchan’s “No Man’s Land” | John Russell’s “The Fourth Man” | E.M. Forster’s “The Machine Stops” | John Buchan’s Huntingtower | Arthur Conan Doyle’s When the World Screamed | Victor Bridges’ A Rogue By Compulsion | Jack London’s The Iron Heel | H. De Vere Stacpoole’s The Man Who Lost Himself | P.G. Wodehouse’s Leave It to Psmith | Richard Connell’s “The Most Dangerous Game” | Houdini and Lovecraft’s “Imprisoned with the Pharaohs” | Arthur Conan Doyle’s “The Sussex Vampire.”

ORIGINAL FICTION: HILOBROW has serialized three novels: James Parker’s The Ballad of Cocky The Fox (“a proof-of-concept that serialization can work on the Internet” — The Atlantic); Karinne Keithley Syers’s Linda Linda Linda (which includes original music); and Robert Waldron’s roman à clef The School on the Fens. We also publish original stories and comics. These include: Matthew Battles’s stories “Gita Nova“, “Makes the Man,” “Imago,” “Camera Lucida,” “A Simple Message”, “Children of the Volcano”, “The Gnomon”, “Billable Memories”, “For Provisional Description of Superficial Features”, “The Dogs in the Trees”, “The Sovereignties of Invention”, and “Survivor: The Island of Dr. Moreau”; several of these later appeared in the collection The Sovereignties of Invention | Peggy Nelson’s “Mood Indigo“, “Top Kill Fail“, and “Mercerism” | Annalee Newitz’s “The Great Oxygen Race” | Flourish Klink’s Star Trek fanfic “Conference Comms” | Charlie Mitchell’s “A Fantasy Land” | Charlie Mitchell’s “Sentinels” | Joshua Glenn’s “The Lawless One”, and the mashup story “Zarathustra vs. Swamp Thing” | Adam McGovern and Paolo Leandri’s Idoru Jones comics | John Holbo’s “Sugarplum Squeampunk” | “Another Corporate Death” (1) and “Another Corporate Death” (2) by Mike Fleisch | Kathryn Kuitenbrouwer and Frank Fiorentino’s graphic novel “The Song of Otto” (excerpt) | John Holbo’s graphic novel On Beyond Zarathustra (excerpt) | “Manoj” and “Josh” by Vijay Balakrishnan | “Verge” by Chris Rossi, and his audio novel Low Priority Hero | EPIC WINS: THE ILIAD (1.408-415) by Flourish Klink | EPIC WINS: THE KALEVALA (3.1-278) by James Parker | EPIC WINS: THE ARGONAUTICA (2.815-834) by Joshua Glenn | EPIC WINS: THE MYTH OF THE ELK by Matthew Battles | TROUBLED SUPERHUMAN CONTEST: Charles Pappas, “The Law” | CATASTROPHE CONTEST: Timothy Raymond, “Hem and the Flood” | TELEPATHY CONTEST: Rachel Ellis Adams, “Fatima, Can You Hear Me?” | OIL SPILL CONTEST: A.E. Smith, “Sound Thinking | LITTLE NEMO CAPTION CONTEST: Joe Lyons, “Necronomicon” | SPOOKY-KOOKY CONTEST: Tucker Cummings, “Well Marbled” | INVENT-A-HERO CONTEST: TG Gibbon, “The Firefly” | FANFICTION CONTEST: Lyette Mercier’s “Sex and the Single Superhero”