Goslings (11)

By:

November 16, 2012

HILOBROW is pleased to present the eleventh installment of our serialization of J.D. Beresford’s Goslings (also known as A World of Women). New installments will appear each Friday for 23 weeks.

When a plague kills off most of England’s male population, the proper bourgeois Mr. Gosling abandons his family for a life of lechery. His daughters — who have never been permitted to learn self-reliance — in turn escape London for the countryside, where they find meaningful roles in a female-dominated agricultural commune. That is, until the Goslings’ idyll is threatened by their elders’ prejudices about free love!

J.D. Beresford’s friend the poet and novelist Walter de la Mare consulted on Goslings, which was first published in 1913. In May 2013, HiLoBooks will publish a beautiful new edition of the book. “A fantastic commentary upon life,” wrote W.L. George in The Bookman (1914). “Mr. Beresford possesses the rare gift of divination,” wrote The Living Age (1916). “It is piece of the most vivid imaginative realism, as well as a challenge to our vaunted civilization.” “At once a postapocalyptic adventure, a comedy of manners, and a tract on sexual and social equality, Goslings is by turns funny, horrifying, and politically stirring,” says Benjamin Kunkel in a blurb for HiLoBooks. “Most remarkable of all may be that it has not yet been recognized as a classic.”

SUBSCRIBE to HILOBROW’s serialized fiction via RSS.

ALL EXCERPTS: 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23

Blanche had chosen well; the fine cloth walking dress admirably fitted her well-developed young figure. When she had discarded her hat and touched up her hair before the glass, only her boots and her hands remained to spoil the disguise. Well gloved and well shod, she might have passed down the Bond Street of the old London, and few women and no man would have known that she had not sprung from the ruling classes.

She posed. She stepped back from the mirror and half-unconsciously fell to imitating the manners of the revered aristocracy she had respectfully studied from a distance.

In a few minutes she was joined by Millie, also arrayed in peacock’s feathers and anxious to be “fastened.”

Their excitement increased. Walking dresses gave place to evening gowns. They lost their sense of fear and ran into other departments searching for long white gloves to hide the disfigurements of household work. They paraded and bowed to each other. The climax came when they discovered a Court dress, immensely trained, and embroidered with gold thread, laid by with evidences of tenderest care in endless wrappings of tissue paper. Surely the dress of some elegant young duchess!

For a moment they wrangled, but Blanche triumphed. “You shall have it afterwards,” she said, as she ran to her dressing-room.

Millie followed in an elaborate gown of Indian silk; a somewhat sulky Millie, inclined to resent her duty of lady’s maid. She dragged disrespectfully at the innumerable fastenings.

“My!” ejaculated Blanche when she could indulge herself in the glory of full examination before a cheval glass in the open show-room. She struggled with her train and when she had arranged it to her satisfaction, threw back her shoulders and lifted her chin haughtily.

“I ought to have some diamonds,” she reflected.

“It drags round the hips,” was Millie’s criticism.

“You should say ‘Your Majesty,’” corrected Blanche.

“Oh! a Queen, are you?” asked Millie.

“Rather —”

“Queen of all the Earth,” sneered Millie.

Blanche’s face suddenly fell. “I wonder if she began like this,” she said, and a note of fear had come into her voice.

Millie’s eyes reflected her sister’s alarm.

“Oh! let’s get out of this, B.,” she said, and began to tear at the neck of her Indian silk gown.

“I wanted diamonds, too,” persisted Blanche.

“Oh! B., it isn’t right,” said Millie. “I said it wasn’t right and you would come.”

Silence descended upon them for a moment, and then both sisters suddenly screamed and ducked, putting up their hands to their heads.

“Goodness! What was that?” cried Blanche.

A swallow had swept in through the open window, had curved round in one swift movement, and shot out again into the sunlight. “Only a bird of some sort,” said Millie, but she was trembling and on the verge of hysterics. “Do let’s get out, B.”

After they had put on their own clothes once more they became aware that they were hungry.

“We have wasted a lot of time here,” said Blanche as they made their way out.

She did not pause to wonder how many women had spent the best part of their lives in a precisely similar manner.

“And we ought to have been looking for food,” she added.

“Come on,” replied Millie. “That place has given me the creeps.”

4

Growing rather tired and footsore they made their way to Piccadilly Circus, and so on to the Strand. Everywhere they found the same conditions: a few skeletons, a few deserted vehicles, young vegetation taking hold wherever a pinch of soil had found an abiding place, and over all a great silence. But food there was none that they were able to find, though it is probable that a careful investigation of cellars and underground places might have furnished some results. The more salient resources of London had been effectively pillaged so far as the West-end was concerned. They were too late.

In Trafalgar Square, Millie sat down and cried. Blanche made no attempt to comfort her, but sat wide eyed and wondering. Her mind was opening to new ideas. She was beginning to understand that London was incapable of supporting even the lives of three women; she was wrestling with the problem of existence. Everyone had gone. Many had died; but many more, surely, must have fled into the country. She began to understand that she and her family must also fly into the country.

Millie still sobbed convulsively now and again.

“Oh! Chuck it, Mill,” said Blanche at last. “We’d better be getting home.”

Millie dabbed her eyes. “I’m starving,” she blubbered.

“Well, so am I,” returned Blanche. “That’s why I said we’d better get home. There’s nothing to eat here.”

“Is — is every one dead?”

“No, they’ve gone off into the country, and that’s what we’ve got to do.”

The younger girl sat up, put her hat straight, and blew her nose. “Isn’t it awful, B.?” she said.

Blanche pinched her lips together. “What are you putting your hat straight for?” she asked. “There’s no one to see you.”

“Well, you needn’t make it any worse,” retorted Millie on the verge of a fresh outburst of tears.

“Oh! come on!” said Blanche, getting to her feet.

“I don’t believe I can walk home,” complained Millie; “my feet ache so.”

“You’ll have to wait a long time if you’re going to find a bus,” returned Blanche.

Three empty taxicabs stood in the rank a few feet away from them, but it never occurred to either of the two young women to attempt any experiment with these mechanisms. If the thought had crossed their minds they would have deemed it absurd.

“Let’s go down by Victoria,” suggested Blanche. “I believe it’s nearer.”

In Parliament Square they disturbed a flock of rooks, birds which had partly changed their natural habits during the past few months and, owing to the superabundance of one kind of food, were preying on carrion.

“Crows,” commented Blanche. “Beastly things.”

“I wonder if we could get some water to drink,” was Millie’s reply. “Well, there’s the river,” suggested Blanche, and they turned up towards Westminster Bridge.

In one of the tall buildings facing the river Blanche’s attention was caught by an open door.

“Look here, Mill,” she said, “we’ve only been looking for shops. Let’s try one of these houses. We might find something to eat in there.”

“I’m afraid,” said Millie.

“What of?” sneered Blanche. “At the worst it’s skeletons, and we can come out again.”

Millie shuddered. “You go,” she suggested.

“Not by myself, I won’t,” returned Blanche.

“There you are, you see,” said Millie.

“Well, it’s different by yourself.”

“I hate it,” returned Millie with emphasis.

“So do I, in a way, only I’m fair starving,” said Blanche. “Come on.”

The building was solidly furnished, and the ground floor, although somewhat disordered, still suggested a complacent luxury. On the floor lay a copy of the Evening Chronicle, dated May 10; possibly one of the last issues of a London journal. Two of the pages were quite blank, and almost the only advertisement was one hastily-set announcement of a patent medicine guaranteed as a sure protection against the plague. The remainder of the paper was filled with reports of the devastation that was being wrought, reports which were nevertheless marked by a faint spirit of simulated confidence. Between the lines could be read the story of desperate men clinging to hope with splendid courage. There were no signs of panic here. Groves had come out well at the last.

The two girls hovered over this piece of ancient history for a few minutes.

“You see,” said Blanche triumphantly, “even then, more’n two months ago, every one was making for the country. We shall have to go, too. I told you we should.”

“I never said we shouldn’t,” returned Millie. “Anyhow there’s nothing to eat here.”

“Not in this room, there isn’t,” said Blanche, “but there might be in the kitchens. Do you know what this place has been?”

Millie shook her head.

“It’s been a man’s club,” announced Blanche. “First time you’ve been in one, old dear.”

“Come on, let’s have a look downstairs, then,” returned Millie, careless of her achievement.

In the first kitchen they found havoc: broken china and glass, empty bottles, empty tins, cooking utensils on the floor, one table upset, everywhere devastation and the marks of struggle; but in none of the empty tins was there the least particle of food. Everything had been completely cleaned out. The rats had been there, and had gone.

Exploring deeper, however, they were at last rewarded. On a table stood a whole array of unopened tins and in one of them was plunged a tin-opener, a single stab had been given, and then, possibly, another of these common tragedies had begun. Had he been alone, that plunderer, or had his companions fled from him in terror?

Here the two girls made a sufficient meal, and discovered, moreover, a large store of unopened beer-bottles. They shared the contents of one between them, and then, feeling greatly reinvigorated, they sought for and found two baskets, which they filled with tinned foods. They only took away one bottle of beer — a special treat for their mother — on account of the weight. They remembered that they had a long walk before them; and they were not over-elated by their discovery; they were sick to death of tinned meats.

In looking for the baskets they came across a single potato that the rats had left. From it had sprung a long, thin, etiolated shoot which had crept under the door of the cupboard and was making its way across the floor to the light of the window. Already that shoot was several feet in length.

“Funny how they grow,” commented Millie.

“Making for the country, I expect,” replied Blanche, “same as we shall have to do.”

It was a relief to them to find their way into the sunlight once more. Those cold, forsaken houses held some suggestion of horror, of old activities so abruptly ended by tragedy. From these interiors Nature was still shut off. That ghostly tendril aching towards the light had no chance for life and reproduction….

5

The two Gosling girls had yet one more adventure before they toiled home with their load.

They were growing bolder, despite the gloom and oppression of those human habitations, and some freakish spirit prompted Blanche to suggest that they should visit the Houses of Parliament. After a brief demur, Millie acceded.

That great stronghold was open to them now. They might walk the floor of the House, sit in the Speaker’s chair, penetrate into the sacred places of the Upper Chamber.

Gone were all the rules and formulas, the intricacies and precedents of an unwritten constitution, the whole cumbrous machinery for the making of new laws. The air was no longer disturbed by the wranglings, evasions and cunning shifts of those who had found here a stage for their personal ambitions. The high talk of progress had died into silence along with the struggle of parties which had played the supreme game, side against side, for the prize of power. Progress had been defined in this place, in terms of human activity, human comfort. The end in sight had been some vague conception of general welfare through accumulated riches. And from the sky had fallen a pestilence to change the meaning of human terms. In three months the old conception of wealth was gone. Money, precious stones, a thousand accepted forms of value had become suddenly worthless, of no more account than the symbol of power which lay coated with dust on the table of the House of law-makers. Even law itself, that slow growth of the centuries, had become meaningless. Who cared if some mad woman plundered every jeweller’s shop in the whole City? Who was to forbid theft or avenge murder? The place of traffic was empty. Only one law was left and only one value; the law of self-preservation, the value of food.

The sunlight fell in broad coloured shafts upon two half-educated girls come on a plundering expedition, and they might sit in the high places if they would, and make new laws for themselves.

Blanche sat for a few moments in the Speaker’s chair.

“It’s a fine big place,” she remarked.

“Oh! come on, B., do,” replied Millie. “I want to get home.”

As they crossed the Square, Millie looked up at Big Ben. “Quarter-past nine,” she said. “It must have stopped.”

“Well, of course, silly,” replied Blanche. “All the clocks have stopped. Who’s to wind ’em?”

XII

EMIGRANT

1

For some time Mrs Gosling was quite unable to grasp the significance of her daughters’ report on the condition of London. During the past two months she had persuaded herself that the traffic of the town was being resumed and that only Putney was still desolate. She had always disapproved of Putney; it was damp and she had never known anyone who had lived there. It is true that the late lamented George Gosling had been born in Putney, but that was more than half a century ago, the place was no doubt quite different then; and he had left Putney and gone to live in the healthy North before he was sixteen. Mrs Gosling was half inclined to blame Putney for all their misfortunes — it was sure to breed infection, being so near the river and all — and she had become hopeful during the past month that all would be well with them if they could once get back to Kilburn.

“D’you mean to say you didn’t see no one at all?” she repeated in great perplexity.

“Those three we’ve told you about, that’s all,” said Blanche.

“Well, o’ course, they’re all shut up in the ’ouses, still; afraid o’ the plague and ’anging on to what provisions they’ve got put by, same as us,” was the hopeful explanation Mrs Gosling put forward.

“They ain’t,” said Millie, and Blanche agreed.

“Well, but ’ow d’you know?” persisted the mother. “Did you go in to the ’ouses?”

“One or two,” returned Blanche evasively, “but there wasn’t no need to go in. You could see.”

“Are you quite sure there was no shops open? Not in the Strand?” Mrs Gosling laid emphasis on the last sentence. She could not doubt the good faith of the Strand. If that failed her, all was lost.

“Oh! can’t you understand, mother,” broke out Blanche petulantly, “that the whole of London is absolutely deserted? There isn’t a soul in the streets. There’s no cabs or buses or trams or anything, and grass growing in the middle of the road. And all the shops have been broken into, all those that had food in ’em, and —” words failed her. “Isn’t it, Millie?” she concluded lamely.

“Awful,” agreed Millie.

“Well, I can’t understand it,” said Mrs Gosling, not yet fully convinced. She considered earnestly for a few moments and then asked: “Did you go into Charing Cross Post Office? They’d sure to be open.”

“Yes!” lied Blanche, “and we could have taken all the money in the place if we’d wanted, and no one any the wiser.”

Mrs Gosling looked shocked. “I ’ope my gels’ll never come to that,” she said. Her girls, with a wonderful understanding of their mother’s opinions, had omitted to mention their raid on the Knightsbridge emporium.

“No one’d ever know,” said Millie.

“There’s One who would,” replied Mrs Gosling gravely, and strangely enough, perhaps, the two girls looked uneasy, but they were thinking less of the commandments miraculously given to Moses than of the probable displeasure of the Vicar of St John the Evangelist’s Church in Kilburn.

“Well, we’ve got to do something, anyhow,” said Blanche, after a pause. “I mean we’ll have to get out of this and go into the country.”

“We might go to your uncle’s in Liverpool,” suggested Mrs Gosling, tentatively.

“It’s a long walk,” remarked Blanche.

Mrs Gosling did not grasp the meaning of this objection. “Well, I think we could afford third-class, she said. “Besides, though we ’aven’t corresponded much of late years, I’ve always been under the impression that your uncle is doin’ well in Liverpool; and at such a time as this I’m sure ’e’ll do the right thing, though whether it would be better to let ’im know we’re comin’ or not I’m not quite sure.”

“Oh! dear!” sighed Blanche, “I do wish you’d try to understand, mother. There aren’t any trains. There aren’t any posts or telegraphs. Wherever we go we’ve just got to walk. Haven’t we, Millie?”

Millie began to snivel. “It’s ’orrible,” she said.

“Well, I can’t understand it,” repeated Mrs Gosling.

By degrees, however, the controversy took a new shape. Granting for the moment the main contention that London was uninhabitated, Mrs Gosling urged that it would be a dangerous, even a foolhardy, thing to venture into the country. If there was no Government there would be no law and order, was the substance of her argument; government in her mind being represented by its concrete presentation in the form of the utterly reliable policeman. Furthermore, she pointed out, that they did not know anyone in the country, with the exception of a too-distant uncle in Liverpool, and that there would be nowhere for them to go.

“We shall have to work,” said Blanche, who was surely inspired by her glimpse of the silent city.

“Well, we’ve got nearly a ’undred pounds left of what your poor father drew out o’ the bank before we shut ourselves up,” said her mother.

“I suppose we could buy things in the country,” speculated Blanche.

“You seem set on the country for some reason,” said Mrs Gosling with a touch of temper.

“Well, we’ve got to get food,” returned Blanche, raising her voice. “We can’t live on air.”

“And if food’s to be got cheaper in the country than in London,” snapped Mrs Gosling, “my experience goes for nothing, but, of course, you know best, if I am your mother.”

“There isn’t any food in London, cheap or dear, I keep telling you,” said Blanche, and left the room angrily, slamming the door behind her.

Millie sat moodily biting her nails.

“Blanche lets ’er temper get the better of ’er,” remarked Mrs Gosling addressing the spaces of the kitchen in which they were sitting.

“It’s right, worse luck,” said Millie. “We shall have to go. I ’ate it nearly as much as you do.”

The argument thus begun was continued with few intermissions for a whole week. A thunderstorm, followed by two days of overcast weather, came to the support of the older woman. One thing was certain among all these terrible perplexities, namely, that you couldn’t start off for a trip to the country on a wet day.

Meanwhile their stores continued to diminish, and one afternoon Mrs Gosling consented to take a walk with Blanche as far as Hammersmith Broadway.

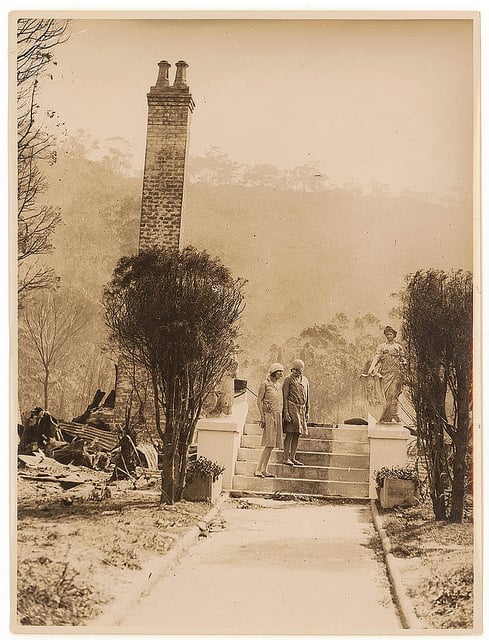

The sight of that blank desert impressed her. Blanche pointed out the house in which she had seen the two women five days before, but no one was looking out of the window on that afternoon. Perhaps they had fled to the country, or were occupied elsewhere in the house, or perhaps they had left London by the easier way which had become so general in the past few months.

When she returned to the Putney house, Mrs Gosling wept and wished she, too, was dead, but she consented at last to Blanche’s continually urged proposition, in so far as she expressed herself willing to make a move of some sort. She thought they might, at least, go back and have a look at Wisteria Grove. And if Kilburn had, indeed, fallen as low as Hammersmith, then there was apparently no help for it and they must try their luck in the waste and desolation of the country. Perhaps some farmer’s wife might take them in for a time, until they had a chance to look about them. They had nearly a hundred pounds in gold.

The girls found a builder’s trolley in a yard near by, a truck of sturdy build on two wheels with a long handle. It bore marks of having held cement, and there were weeds growing in one end of it, but after it had been brought home and thoroughly scrubbed, it looked quite a presentable means for the transport of the “necessaries” they proposed to take with them.

They made too generous an estimate of essentials at first, piling their truck too high for safety and overtaxing their strength; but that problem, like many others, was finally solved for them by the clear-sighted guidance of necessity.

They started one morning — a Monday if their calculations were not at fault — about two hours after breakfast. Mrs Gosling and Millie pushed behind, and Blanche, the inspired one, went before, pulled by the handle of the pole and gave the others their direction.

It is possible that they were the last women to leave London.

By chance they discovered the Queen of all the Earth on a doorstep near Addison Road. She was quite dead, but they did not despoil her of the jewels with which she was still covered.

RADIUM AGE SCIENCE FICTION: “Radium Age” is HILOBROW’s name for the 1904–33 era, which saw the discovery of radioactivity, the revelation that matter itself is constantly in movement — a fitting metaphor for the first decades of the 20th century, during which old scientific, religious, political, and social certainties were shattered. This era also saw the publication of genre-shattering writing by Edgar Rice Burroughs, Sax Rohmer, E.E. “Doc” Smith, Jack London, Arthur Conan Doyle, Aldous Huxley, Olaf Stapledon, Karel Čapek, H.P. Lovecraft, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Yevgeny Zamyatin, Philip Gordon Wylie, and other pioneers of post-Verne/Wells, pre-Golden Age “science fiction.” More info here.

HILOBOOKS: The mission of HiLoBooks is to serialize novels on HiLobrow; and also, as of 2012, operating as an imprint of Richard Nash’s Cursor, to reissue Radium Age science fiction in beautiful new print editions. So far, we have published Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague, Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”), Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt, H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook, Edward Shanks’s The People of the Ruins, William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land, and J.D. Beresford’s Goslings. Forthcoming: E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man, Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage, and Muriel Jaeger’s The Man with Six Senses. For more information, visit the HiLoBooks homepage.

SERIALIZED BY HILOBOOKS: Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague | Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”) | Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt | H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook | Edward Shanks’ The People of the Ruins | William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land | J.D. Beresford’s Goslings | E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man | Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage | Muriel Jaeger’s The Man With Six Senses | Jack London’s “The Red One” | Philip Francis Nowlan’s Armageddon 2419 A.D. | Homer Eon Flint’s The Devolutionist | W.E.B. DuBois’s “The Comet” | Edgar Rice Burroughs’s The Moon Men | Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s Herland | Sax Rohmer’s “The Zayat Kiss” | Eimar O’Duffy’s King Goshawk and the Birds | Frances Hodgson Burnett’s The Lost Prince | Morley Roberts’s The Fugitives | Helen MacInnes’s The Unconquerable | Geoffrey Household’s Watcher in the Shadows | William Haggard’s The High Wire | Hammond Innes’s Air Bridge | James Branch Cabell’s Jurgen | John Buchan’s “No Man’s Land” | John Russell’s “The Fourth Man” | E.M. Forster’s “The Machine Stops” | John Buchan’s Huntingtower | Arthur Conan Doyle’s When the World Screamed | Victor Bridges’ A Rogue By Compulsion | Jack London’s The Iron Heel | H. De Vere Stacpoole’s The Man Who Lost Himself | P.G. Wodehouse’s Leave It to Psmith | Richard Connell’s “The Most Dangerous Game” | Houdini and Lovecraft’s “Imprisoned with the Pharaohs” | Arthur Conan Doyle’s “The Sussex Vampire.”

ORIGINAL FICTION: HILOBROW has serialized three novels: James Parker’s The Ballad of Cocky The Fox (“a proof-of-concept that serialization can work on the Internet” — The Atlantic); Karinne Keithley Syers’s Linda Linda Linda (which includes original music); and Robert Waldron’s roman à clef The School on the Fens. We also publish original stories and comics. These include: Matthew Battles’s stories “Gita Nova“, “Makes the Man,” “Imago,” “Camera Lucida,” “A Simple Message”, “Children of the Volcano”, “The Gnomon”, “Billable Memories”, “For Provisional Description of Superficial Features”, “The Dogs in the Trees”, “The Sovereignties of Invention”, and “Survivor: The Island of Dr. Moreau”; several of these later appeared in the collection The Sovereignties of Invention | Peggy Nelson’s “Mood Indigo“, “Top Kill Fail“, and “Mercerism” | Annalee Newitz’s “The Great Oxygen Race” | Flourish Klink’s Star Trek fanfic “Conference Comms” | Charlie Mitchell’s “A Fantasy Land” | Charlie Mitchell’s “Sentinels” | Joshua Glenn’s “The Lawless One”, and the mashup story “Zarathustra vs. Swamp Thing” | Adam McGovern and Paolo Leandri’s Idoru Jones comics | John Holbo’s “Sugarplum Squeampunk” | “Another Corporate Death” (1) and “Another Corporate Death” (2) by Mike Fleisch | Kathryn Kuitenbrouwer and Frank Fiorentino’s graphic novel “The Song of Otto” (excerpt) | John Holbo’s graphic novel On Beyond Zarathustra (excerpt) | “Manoj” and “Josh” by Vijay Balakrishnan | “Verge” by Chris Rossi, and his audio novel Low Priority Hero | EPIC WINS: THE ILIAD (1.408-415) by Flourish Klink | EPIC WINS: THE KALEVALA (3.1-278) by James Parker | EPIC WINS: THE ARGONAUTICA (2.815-834) by Joshua Glenn | EPIC WINS: THE MYTH OF THE ELK by Matthew Battles | TROUBLED SUPERHUMAN CONTEST: Charles Pappas, “The Law” | CATASTROPHE CONTEST: Timothy Raymond, “Hem and the Flood” | TELEPATHY CONTEST: Rachel Ellis Adams, “Fatima, Can You Hear Me?” | OIL SPILL CONTEST: A.E. Smith, “Sound Thinking | LITTLE NEMO CAPTION CONTEST: Joe Lyons, “Necronomicon” | SPOOKY-KOOKY CONTEST: Tucker Cummings, “Well Marbled” | INVENT-A-HERO CONTEST: TG Gibbon, “The Firefly” | FANFICTION CONTEST: Lyette Mercier’s “Sex and the Single Superhero”