Not trash, Pop – The Cartoon Art of Susi

By:

October 27, 2012

This post is a sequel to a more informal post at Crooked Timber, in which I wrote:

“A family friend, Susi, just turned 90. Since I’m home in Oregon, I attended the B-Day party. Her Jewish family got out of Germany in ’39 and she found herself a teenager in the US. Got an education, got married, raised a family. She was — is — an artist, and she ended up teaching. But she worked as a gag strip cartoonist in New York, from ’46 to ’50. I’m interested in the history of comics, so she loaned me a rather large file box (which I am being very careful with!) Lots of old clippings, old battered bristol board with typed captions taped on. Neat!

I have an undated piece of paper here stating that, ‘during recent months cartoons by Susi Steinitz have appeared in: Holiday, Colliers, This Week, Ladies Home Journal, American Legion, Look, True, Esquire, Argosy, Saturday Review, American Weekly, Nation’s Business, Parade, 47, Parents Magazine, Everybody’s Digest, The Woman, Pathfinder, Everybody’s Weekly, Judge.’”

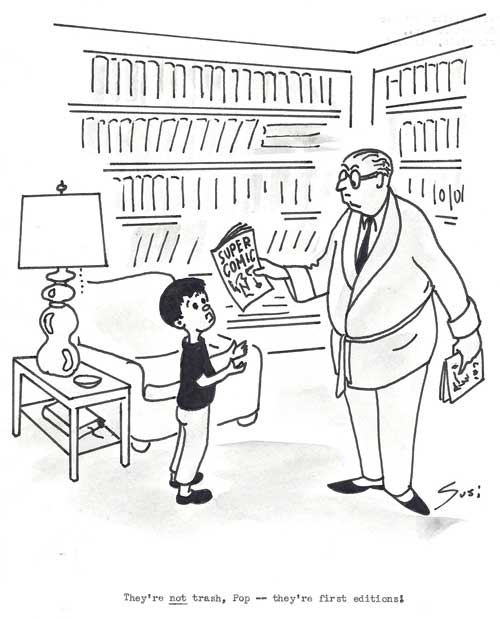

After posting, I conducted a full interview with Susi — full name: Susi Steinitz Ettinger. Well, really more a case of the two of us plain old talking. And emailing since. For example, I asked whether, when she drew this one (sometime in the early ’50s) she had any notion that the kid was, quite simply, correct?

Nope. She can recall crediting no such outlandish notion.

But first things first: minor corrections. In the CT post I said she was the only female cartoonist working in New York at the time. That turns out not to be right (whether I misheard or Susi misspoke, I couldn’t say.) I got in contact with Seth — yes, that Seth — who I presumed to be just the sort to be healthily interested in Susi’s story (since, after all, her story happened in the past.) He graciously provided, off the top of his head, three female names, and expressed confident belief there were at least a few more: Helen Hokinson, Barbara Shermund, and M. Blanchard. I ran these names past Susi who turned out to know Hokinson’s stuff. She remembered right away that Hokinson died young in a plane crash. She hadn’t known her personally. Susi remarked that her later stuff (this one I posted to CT, for example) was similar to Hokinson’s. Ship’s prow-bosomed matron-types, plowing the waves of the high seas of modern life and literature. (Seth said he noticed the similarity, too!) She’d heard of Shermund, too, but not Blanchard.

Second, re: Jewishness. Susi emails: “my family have been free-thinkers and agnostics since the 18th century.” No need to let the racism of the Third Reich cast a longer shadow than necessary, I’m sure we can agree.

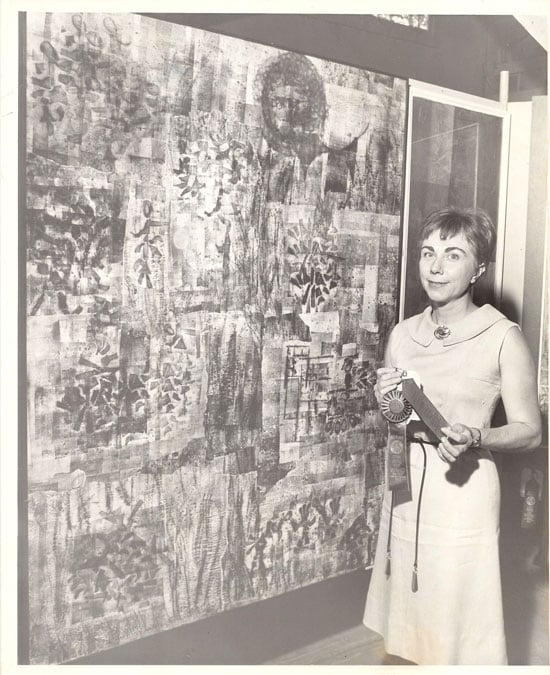

Here’s a nice recent picture of Susi. (Recent is relative. I think this one is about 15 years old.)

Let’s move on to biography. (This might get a bit wiki-ish, or just plain into the weeds; but I feel I am, in part, trying to document a some history here. Comics history and, we’ll see, a bit of modern art history. Someday somebody doing research is going to Google this post and be glad I wrote it!)

Susi writes:

Susi Ettinger was born in Berlin, Germany in 1922. As a young child, she spent time in the home of her aunt, Kate Steinitz, rubbing elbows with artists who later became part of the German avant garde, including Kurt Schwitters, El Lissitsky and Hanna Höch. In 1939 she emigrated with her parents to the United States. After a few months attending high school in New York City, she entered the University of Louisville and earned a Bachelor of Fine Arts Degree in Art History in 1943. She had the good fortune to study with the art historian Justus Bier. For her BFA research, she wrote one of the first investigations in English of the Swiss artist Paul Klee. Her first job was as a lecturer at the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

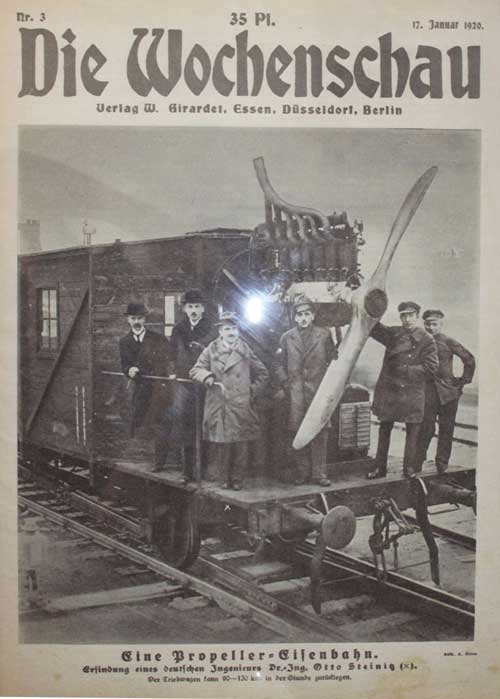

A bit more biographical detail. Her father was Otto Steinitz, an engineer who patented a propeller-driven train. (Sorry for lensflare. Non-ideal shooting conditions.)

Father is the short one, third from left. (Susi emails: He was also a patent attorney and design engineer for Hermann Oberth.)

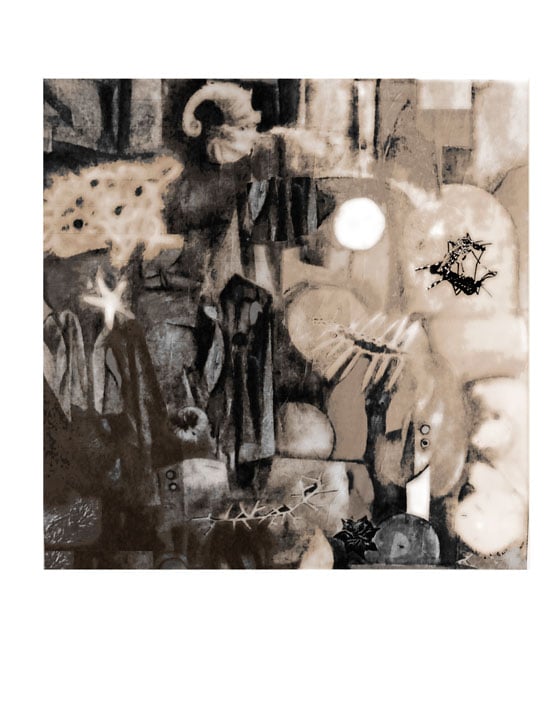

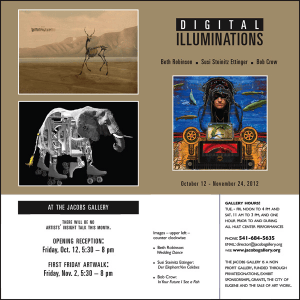

At 90, Susi is still making art — she’s got a show on right now, in Eugene, Oregon: information at the bottom of the post — and some of her work incorporates mementos of her father’s work.

[Click for larger]

Six framed projection slides (I think they are). “Just A Dream Then”, she calls it.

More about the family: Kate Steinitz, Susi’s paternal aunt, did more than feed fond early childhood memories. Kate — Katherine; Kätte or Käthe — emigrated to America a few years earlier, landed on her feet in the New York art world, and was instrumental in arranging the last-minute escape from Germany of her brother’s family. Kate got an American friend, William Suhr, an art restorer, to intercede and offer critical sponsorship to the Steinitzes at a point when, apparently, Otto had all but given up hope.

Susi vividly remembers getting to walk to the front of a line. Desperate people were wrapped all the way around the block, at the American Embassy.

When they got the America, Kate’s support continued. Susi got to attend artist-only early openings at MoMA, got to know the museum well, and was able to win admission to the University of Louisville at the tender age of 17 because a refugee assistance group was impressed by her MoMA tour guide skills.

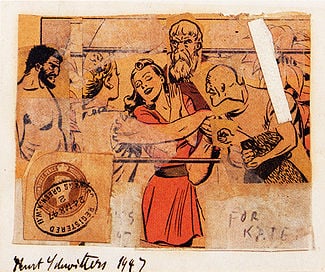

Aunt Kate, by the by, is the Kate to whom Kurt Schwitters’ “For Käte” comics collage is dedicated:

Schwitters is often credited with anticipating Pop Art with this piece. But the material basis for the collage was provided by Kate. She sent care packets of food to Schwitters, in England. Susi says: “She was trying to keep him from starving.” Jars of nourishing peanut butter, and so forth, came each individually wrapped in American comics. Not trash, pop! Grade-A Merz fodder — and intended as such by Kate.

More from Susi:

After the war, she [Susi] worked from 1946-1952 as a freelance cartoonist in New York, often teaming with her husband Manford Ettinger, who wrote short humor pieces. Her cartoons appeared in major magazines of the day, including The Saturday Review, Look, Collier and Esquire.

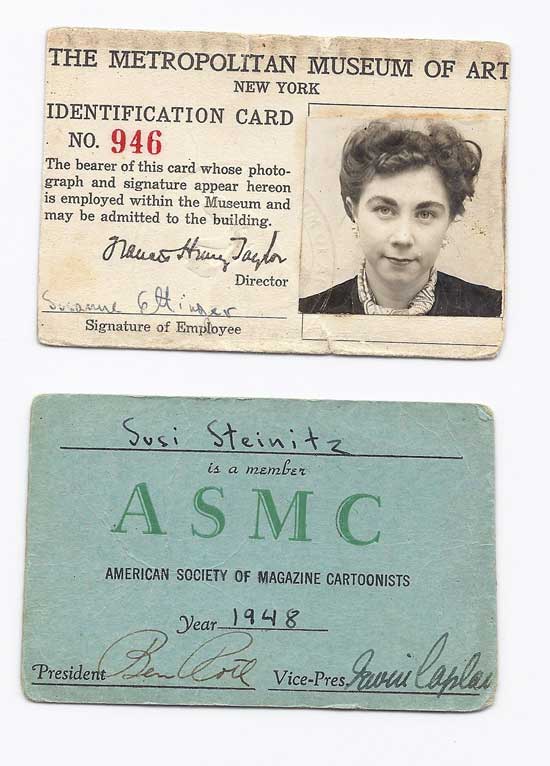

More clarification. She worked as a Met lecturer after college: 1943. But when the boys came home she got laid off, like so many other women. So: 1946 was when she started making a living as a cartoonist. Here’s her Met employee card (it rained that day. She didn’t know they were going to take her picture. Ah, well. Too late now to do anything about that hair now.) Also, confirmation of her professional cartooning credentials!

The American Society of Magazine Cartoonists does not have much web presence. I wonder, I wonder. This Wikipedia entry for one Lawrence Lariar confirms it had some existence in approximately the right period.

Her membership card seems to be signed by President … Ben Roth (!) And Vice-Pres (?) Caplan?

Roth, I deduce, was one of the four cartooning Roth brothers, another of whom was Salo. That name I knew. Seth’s mythical Kalo, in It’s a Good Life, If You Don’t Weaken, is a play on Salo. I’m right, right?

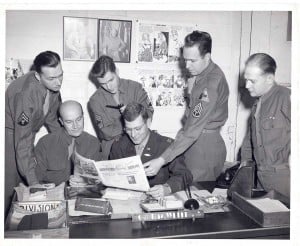

Susi actually started cartooning in college. Her husband, Manford, whom she met in Kentucky, was an editor of Armored News, out of Fort Knox. It ran two years, during the war. She let me scan this great photo.

[Click for larger]

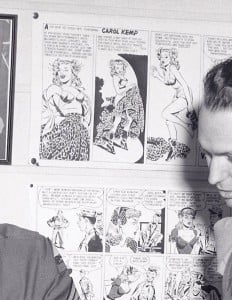

That’s Sgt. M.F. Ettinger, second from the right. (Back page says something about “allied plunge into Germany” so probably late ’44.) Detail in the background. Carol Kemp? Never heard of it. (Torchy-looking stuff.)

As I was saying, Susi worked briefly as a cartoonist for Armored News, so she took it up again after getting laid off at the Met.

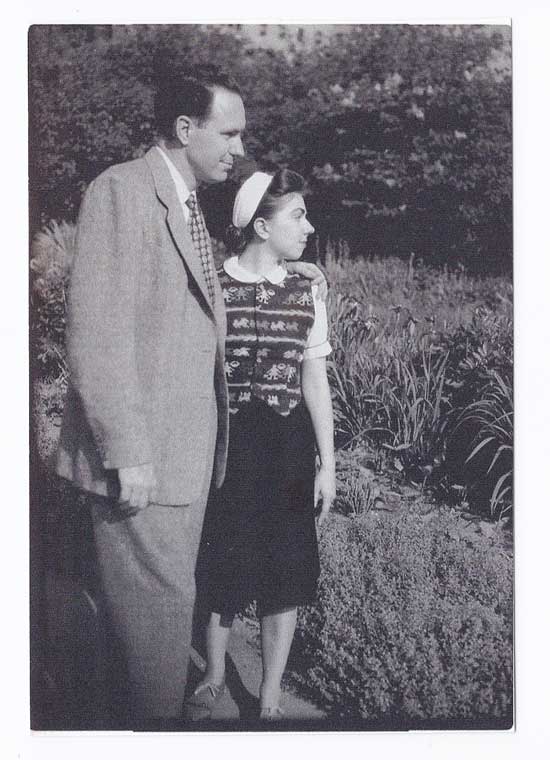

Here’s a nice picture of Susi and husband (except it didn’t scan well. One of those old photos that has nubbly texture.)

Here’s how the biz works: you shop your “roughs” around New York once a week — on Wednesdays, it was. Take a batch to editor so-and-so and sell what you can, then on down the pay-rate food chain until your feet get too tired or the sun goes down or something. You could do it by mail, and Susi and Manford did mail-ins for publications not based in New York. But it was inefficient having to wait so long that way; stuff getting lost.

Format was standard. Caption typed at bottom. Cartoonist’s name and return address stamped on the back. (This is the only way I have been able to make heads-or-tails of Susi’s strip box’s contents, incidentally. Absolutely every piece of paper, except for just a few very rough sketches, had a return address. Susi lived at three addresses: New York, then New Jersey, then Missouri. No dates. Dating art by return address is pretty uncertain. Clearly there was recycling and redrawing of earlier material.)

Pay wasn’t great but living was relatively easy — until the kids showed up. Susi and Manford would spend a couple days a week working out gags, she would draw them, he would market them. You could take a lot of weekdays off, as well as your weekends; go to the museum, go to the shore.

Now comes the point where I tell you all the great stories Susi told me about how crazy it was, making your way in New York after the war, as a diminutive female cartoonist. And shy! (she says.) Alas, she didn’t have so many stories to tell. Her husband — army vet, 15 years her senior (and tall!) — seems to have had the good sense to prevent most of those stories from happening by doing almost all the shoe leather and glad-handing editors work himself. He was good at it, Susi says. So good at researching markets and making connections that, briefly, he and Susi put together a newsletter for cartoonists, containing the kind of information some cartoonists had been trying to glean by tailing him around New York on his weekly rounds. (Also: he had some kind of numbering system for Susi’s box of work. I can’t make sense of it, and Susi says she doesn’t know. The numbers run up into the 2000’s. Presumably that’s how many cartoons she drew and/or redrew. 500+ survive.)

She did tell one good story. The cartoonists of the American Cartoon Arts Society (or was this again the American Society of Magazine Cartoonists?) met in the Pen and Pencil, a club/watering hole somewhere in Manhattan. (I can find no evidence on the internet of such an establishment.) She didn’t go out much, but could remember two names: Bernie Wiseman and Jeff Keate.(Ooh, ooh! I’ve got one of Wiseman’s books on my shelf! Because I collect corny sf-themed stuff! Also, she knew Barney Tobey (who, unaccountably, has no Wikipedia page.)

As I was saying: pregnant, at a Christmas, 1947 Pen and Pencil party, she overhead fellow cartoonists forming a betting pool for the baby’s birthday. Linda was born on National Cartoonist Day, April 7, 1948. Except the internet knows naught of such a holiday, so perhaps she is half-remembering some other gag that arose over the baby’s birth? Maybe they christened it Cartoonist’s Day in honor of the baby one night? I couldn’t say. (Susi emails: “April 7 was National Cartoonists Day , no matter what Google says!”)

She won a prize from the American Cartoon Art Society in 1948 for a strip in which someone is trying to teach a parrot to say ‘No, Polly wants a Sunshine Brand Cracker’.

The editor of The Saturday Review, Norman Cousin, was the nicest guy. He treated all cartoonists ‘like human beings’. Lots of other editors ‘wanted a date, only they didn’t really want a date’.

One editor at Esquire was getting increasingly annoying. She started signing her cartoons ‘Susi’ instead of ‘Steinitz’, on the theory that he would stop buying them if it was going to be obvious to his readers the cartoonist was female. And he did! (Science fact!) But ‘Susi’ stuck as a signature, apparently, even after she ceased to be concerned with annoying Esquire’s editor, per se.

These, and many other details, lost to history are, presumably, among the reasons her husband mostly handled editors.

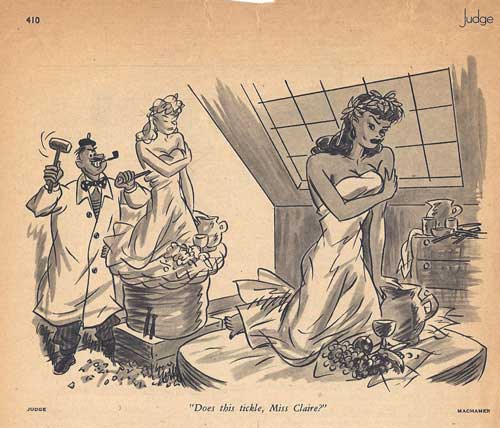

Someone asked me to ask her that timeless question: “Was Jefferson Machamer a nice guy or a twit?” She didn’t recognize the name. He was a ‘gags and gals‘ guy, I explained. ‘Oh, that sort of stuff.’ Funnily enough, I promptly found a Machamer strip in Susi’s file, from Judge. But it was only there because one of hers was on the reverse:

Yet Machamer failed to make any impression, despite such manly effort, on Susi Ettinger.

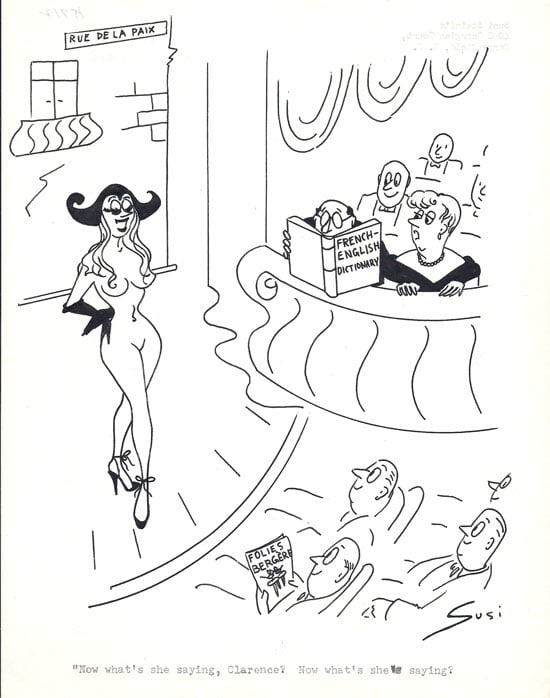

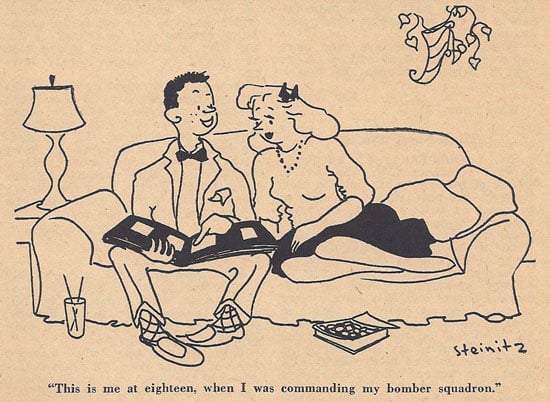

Susi didn’t do that sort of stuff – not that there’s anything wrong with that! – but one of her funniest strips, in my opinion, also happens to be her hotsy totsiest. It’s one she did in the ’50s, when she was living in Missouri. (Who knows whether it has ever been published before?)

Seems a good point to add some more biography:

Ettinger served on the faculty in the Art Department at Southwest Missouri State University rrom 1964-1984. She taught basic design, drawing, painting and art appreciation for humanities students. Building on her unique background, she also developed and taught a seminar on modem German art. She is Emeritus Lecturer in Art. Her exhibition resume includes 5 one-woman shows and many regional and national exhibitions. Her work is in the permanent collections of the Springfield Missouri Art Museum and the College of the Ozark, the Missouri State Historical Society art collection – and numerous private collections in the U.S. and Europe.

So it all came out alright, but maybe being a trailing spouse to Missouri was a bit of a letdown after the Big Apple. For a while, she thought she might be able to keep up the cartooning. But it faded out. Kids, life. Too hard to manage by mail.

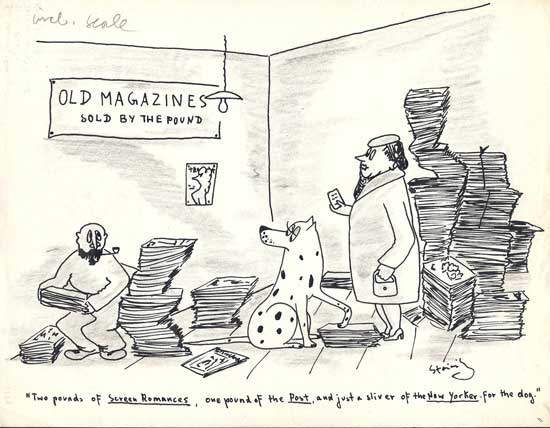

I asked her about her stylistic influences (her style is really surprisingly variable). The earliest surviving piece in the box would seem to be this one:

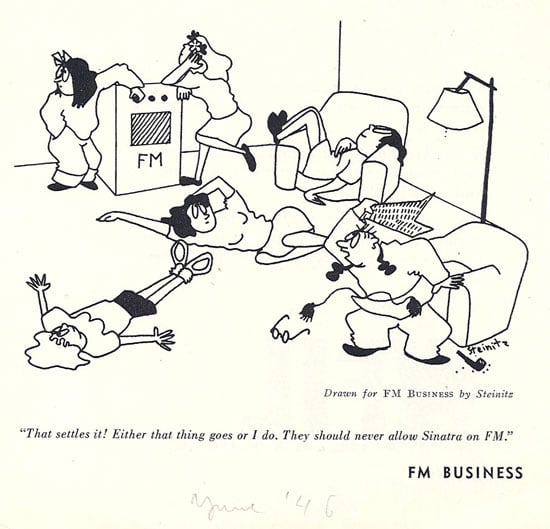

A lot of the early stuff exhibits what she refers to as her “squashed people” style. Susi has several FM radio-themed cartoons in her file, per the rather narrow demands on one particular client. (This one is dated June ’46, as you can see.)

Speaking of style, why did she read as a girl in Germany? Any cartoon influences? Initially, she remembered reading Ulk and Lustige Blätter.

Simplicissimus, I suggested? Yes!

Max und Moritz? Of course! Later, after we talked, she made a list and added: Paul Simmel, George Grosz, Fliegende Blätter. (Lots of art in the house, growing up. Always drawing as a kid.)

Krazy Kat? I was thinking she might have gotten to know it after coming to America, but she felt she had already seen it in Germany, which is interesting. (Or else she’s misremembering.)

What about after coming to America? Robert Benchley, Saul Steinberg and Ronald Searle. (But the Searle must have come a bit later.)

Did cartooning help her learn English. Did she bridge language difficulties with pictures? Not really. How did she learn English? She remembers listening to Edward Murrow, “Reports From London”, about the war. He had a great voice. That made a big, linguistic impression. Also, movies. She liked the big screen names: Grant, Davis, Hepburn.

She read PM, a leftist New York newspaper. So she presumably saw a lot of Theodor Geisel (Dr. Seuss) stuff. He published in PM. She remembered reading and enjoying Pogo, in PM. But, checking, Pogo only appeared in its successor, The Star. She tried to describe another strip with a bald kid, from PM – what was the name? Checking, it must have been Barnaby.

Charles Addams? Oh, yes! The New Yorker stuff? All of that of course! Gasoline Alley. Li’l Abner, Milt Caniff? Winsor McCay? No, no, no. No to some other titles I rattled off.

Susi gave me an old, battered Gurney Williams book, I Meet Such People!, inscribed to her husband by the author. (You can pick up a copy yourself for a couple bucks on Amazon.) It’s an anthology of gag cartoons from Colliers, where Gurney was editor, with text by Williams, mostly talking shop in what I would characterize as a corny, insincere, sub-Stan Lee Excelsior! authorial voice. (Williams explains all about shopping roughs around; why cartoonists won’t necessarily be happy to give you some old, already-published drawing, since they are maybe hoping to resell it eventually. Hence my difficulties dating various cartoons in Susi’s file. Who knows how many times a given strip has been redrawn or maybe resold?)

Having dug out the Williams book, to hand it to me, she flipped through it: a lot of this stuff looks like my stuff, she says with some surprise. It’s a bit surprising that this would be surprising (seems to me.) She says she never really thought about it. She just messed around, trying to come up with something good that would sell.

Did she think what she was doing — gag cartooning — was art? Respectable commercial illustration work? Hack-work? Secret, undiscovered soul of modern art? Was she worried what her art teachers would think? (Or that Dwight Macdonald or Clement Greenberg would get mad at her?) Was she proud to be a cartoonist? Did she think of it as a career — something she might still be doing in 20 years? Did it seem like some weird, temporary thing?

You can see me angling for some sort of high-brow/low-brow conflict angle on Susi’s cartooning career. But Susi didn’t really take the bait.

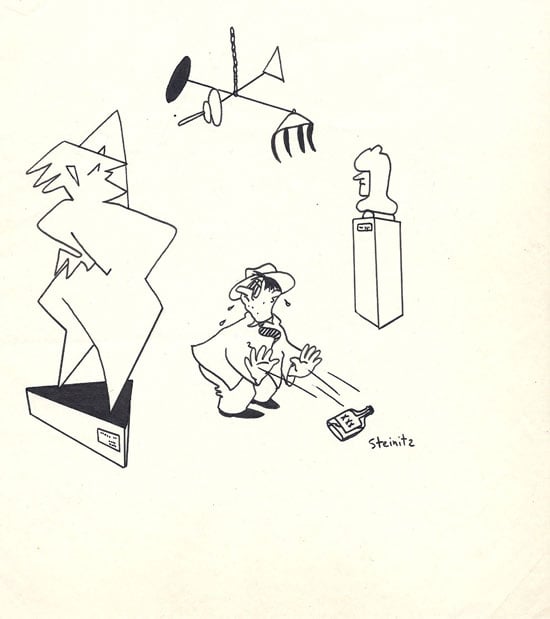

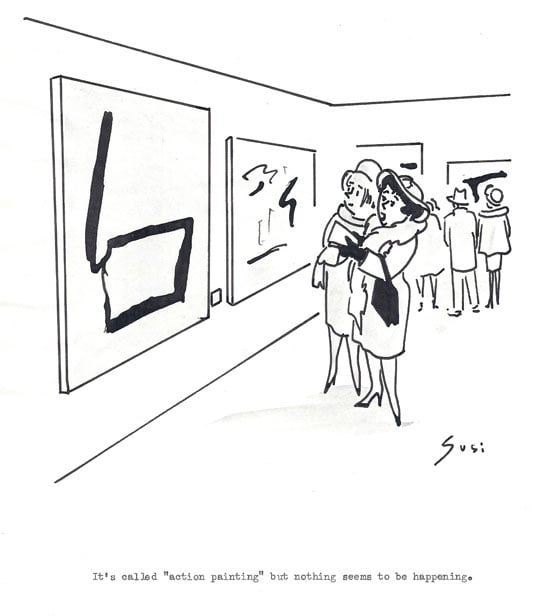

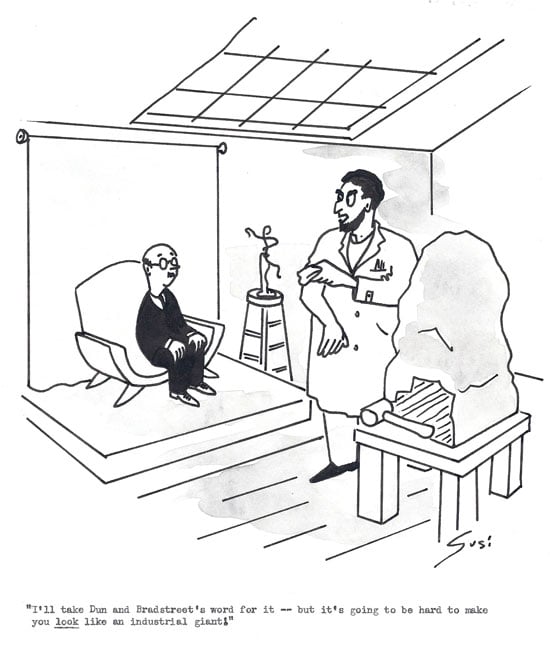

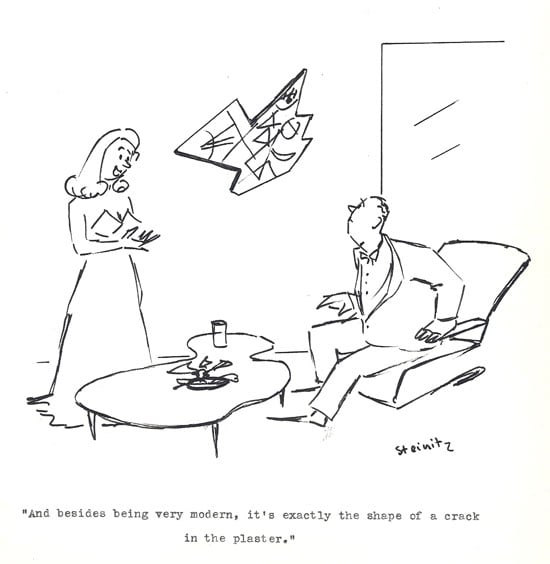

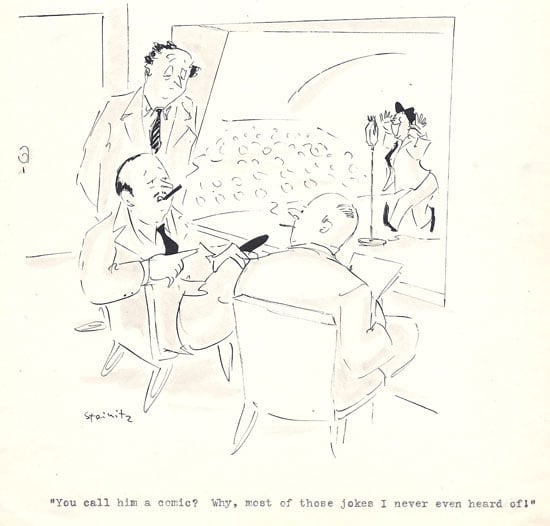

She does have a number of cartoons about modern art, from all stages of her career.

But collisions between the likes of modern life, modern drink, and modern art, are classic gag cartoon fodder, aren’t they?

Thinking back, Susi thinks she didn’t think about it that much. The war meant you grew up quick. Then again, not — I suppose.

From the time it became clear her family had no future in Germany she wanted to come to America (her father had been hoping to get to England.) When she got to America, she didn’t look back. She wanted nothing to do with Germany ever again. She told me it took her decades to get over this. But this hostility did not extend to the European high art tradition, or to modern art. Again, understandable — especially thanks to the likes of Aunt Kate.

Which is not to suggest these Susi strips are bold, original works of modern art. Gag cartooning, as many a critic has complained, is a conservative and cliche-ridden form. Regression to the mean — reversion to mediocrity, the statisticians used to say — has some conceptual application here. Had this file of Susi’s collected cartoon works been lost to history, one might have deduced it must have contained a certain number of secretary jokes — the dumb one, the harassed one; an assortment of eccentric bosses whose underlings must endure them; cavemen who bonk women on the head, as a presumable preliminary to dragging them back to caves; so on. You would not have been wrong. But, then again: you can complain about people who crave comfort food. But it doesn’t make sense to suggest that comfort food should be bold and original.

Of course, Dwight Macdonald will now complain about people who want comfort food — cultural comfort food, that is. He abominates the stuff for the way it narrows vision down to the inconsequential, then flourishes this deformation as discovery. Gag cartoons seem to function as cheap proofs-by-example of an easy, “vanity, all is vanity” wisdom.

The wonder of it all is that this is exactly wrong (even though the indictment seems to make a great deal of sense). Wrong! If you don’t believe me, read any book by Seth.

Or pull down from your shelf a handy copy of Varnedoe and Gopnik’s High and Low, Modern Art and Popular Culture. Flip to the chapter on Comics and read the discussion of Schwitters and “For Kate”:

The prewar collages of Schwitters had conveyed the darkling melancholy of decaying Middle Europe, structured by an uneasy truce between the last remnants of the confident nineteenth century and the austere utopian geometry of modern style … But in 1947, the elements of Merz are no longer little snippets from an economy of scarcity, nuggets of information and records of commerce tidily saved like cigarette butts; they are now bug chunks of bright fatuous color, a souvenir from the land of the lotus-eaters.

For the rest of the century the comics as a subject for art would remain inseparable from the matter of America. Seen from a distance, especially, the comics, good, bad and indifferent, were an emblem of the triumph of American popular culture, a flood of songs and rhythms and bright images that was to the American empire what hot water had been to the Roman. By the middle of the 1950’s, this triumphant (or devouring) pop culture had become, by attraction and repulsion, one of the central events and issues of European culture. For Miró and Picasso, the comic strip had still some of the universality that Goethe had hoped to invest it with; after the war, the comics just said America. (185).

It’s too bad Susi gave up gag cartooning because, frankly, the Missouri-era stuff was getting better and better. (Not just because the ladies are now taking the occasion club to a caveman, rather than vice versa!)

Originally a deodorant slogan, I believe.

Susi, as I said, kept up her art. Here she is, in front of one of her paintings, in 1967.

And, at the age of 90, she has a gallery show in Eugene, OR. Go see it before November 2!

Her work these days is digital. Collage stuff. Photoshop compensates for unsteady draftsmanship that is entirely to be expected in one’s ninth decade. I like “Summer Night”.