The Man Who Saw a Ghost

By:

October 11, 2012

Devin McKinney — author of the amazing book Magic Circles: The Beatles in Dream and History (Harvard), and a HiLobrow contributor — has a new book out this week: The Man Who Saw a Ghost: The Life and Work of Henry Fonda. I interviewed him about the project last week, for the Boston Globe Ideas section’s BRAINIAC blog. Here is that exchange.

BRAINIAC: Henry Fonda died 30 years ago. It’s hard to argue that he still carries the same cultural weight as his contemporaries John Wayne or Ronald Reagan, let alone later icons like Marilyn Monroe and James Dean. Why does Fonda matter today?

MCKINNEY: Fonda practiced his art at a certain peak of intensity, mystery, commitment, and suggestiveness, and that always matters. In the more ephemeral sense — “What has Henry Fonda done for me lately?” — he matters as a measure of how an artist can express an ongoing critique of America. Bush II was president when I began writing, Obama when I finished. In those years, millions of us were going through convulsions of fear, outrage, anger, hope, exultation, compromise, betrayal. But what ran through all of it was the unspoken edict, from right and left, that America is not to be criticized. Policies may be wrong, the other party may be evil, but America itself is nothing but good. The people are nothing but good. Our global mission, whatever we need that to be this year or next, is righteous and God-blessed. And it became accepted that any questioning of that essential goodness was tantamount to treason. It was to fail the litmus test of American exceptionalism.

I see exceptionalism as a heinous doctrine. I don’t believe Henry Fonda was an exceptionalist. He took for granted in his work that American democracy is yet to be perfected, and that it’s the patriot’s obligation to critique it, poke it, watchdog it, be suspicious of it. In the years I was writing this book, that seemed to me the rarest gift an American artist could give, and Fonda gave it consistently over the course of nearly 50 years on the screen. He made me feel pride and strength in American capability in times when it seemed so much of our capability was only selfish, lazy, cruel, murderous. I trust that dimension of his relevance will come through to readers who have felt the same frustrations.

BRAINIAC: Did you have personal reasons for wanting to write about Fonda?

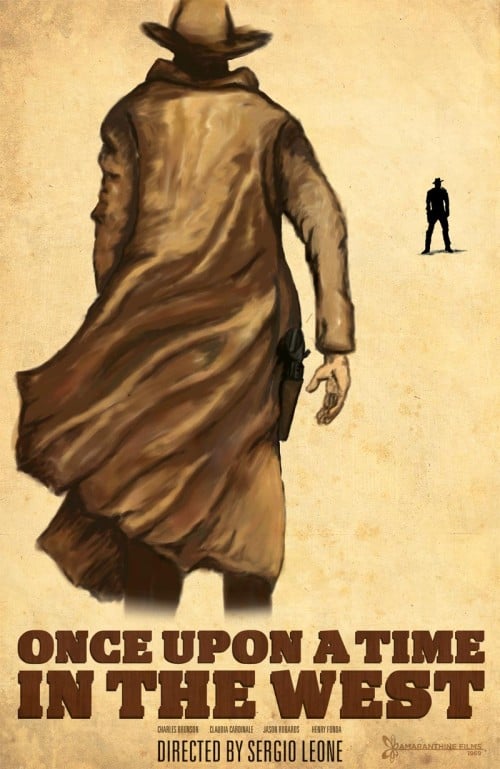

MCKINNEY: There were many. My previous book was about the Beatles, and I wanted to take on a very different subject. Henry Fonda had starred in my favorite movie of all time, Once Upon a Time in the West, and a lot of others I wanted to rediscover. He’d been a star of both screen and stage, so the very different worlds of Hollywood and Broadway came together in him. He lived through interesting times and knew interesting people. He had interesting kids in Jane and Peter, and I wanted to trace out his influence on them. His political engagements in movies and in life were another rich area to explore. His life was full of sorrow and occasional tragedy, and that came back through his work in ways that intrigued me.

As much as anything, I felt something for Henry Fonda because like me he was from the Midwest, specifically Nebraska, and I always felt attuned to his stoicism and his submerged anger, along with his gravity and strength. He reminded me of my grandfather, of my father, of myself, of almost every man I knew growing up. Through him, I thought I’d get some insight into myself and where I come from — which is the only true reason you ever choose a subject.