Goslings (5)

By:

October 5, 2012

HILOBROW is pleased to present the fifth installment of our serialization of J.D. Beresford’s Goslings (also known as A World of Women). New installments will appear each Friday for 23 weeks.

When a plague kills off most of England’s male population, the proper bourgeois Mr. Gosling abandons his family for a life of lechery. His daughters — who have never been permitted to learn self-reliance — in turn escape London for the countryside, where they find meaningful roles in a female-dominated agricultural commune. That is, until the Goslings’ idyll is threatened by their elders’ prejudices about free love!

J.D. Beresford’s friend the poet and novelist Walter de la Mare consulted on Goslings, which was first published in 1913. In May 2013, HiLoBooks will publish a beautiful new edition of the book. “A fantastic commentary upon life,” wrote W.L. George in The Bookman (1914). “Mr. Beresford possesses the rare gift of divination,” wrote The Living Age (1916). “It is piece of the most vivid imaginative realism, as well as a challenge to our vaunted civilization.” “At once a postapocalyptic adventure, a comedy of manners, and a tract on sexual and social equality, Goslings is by turns funny, horrifying, and politically stirring,” says Benjamin Kunkel in a blurb for HiLoBooks. “Most remarkable of all may be that it has not yet been recognized as a classic.”

SUBSCRIBE to HILOBROW’s serialized fiction via RSS.

ALL EXCERPTS: 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23

“But let us consider for a moment,” wrote Thrale, “the appalling danger which threatens us when we are attacked by a pestilence which is entirely new to humanity; new, so far as we know, to the world. In the middle of the fourteenth century the Black Death is recorded in some places to have killed two-thirds of the whole population, and, notwithstanding the modern improvement in sanitation and general hygiene, there is no inherent reason why another pestilence may not appear, which may be even more deadly. And we are faced at the present moment with the awful threat that such a pestilence has appeared, the pestilence commonly known as the ‘new plague.’ There is no reason why we should consider the appearance as without precedent in history; there is no reason why we should regard its coming as outside the laws of common probability; finally, and most decisively, there is no reason why England should not be smitten.

“According to report among the Chinese, this ‘new plague’ has been spasmodically epidemic in Tibet for more than a century. We have, as yet, no certain facts upon which to base any hypothesis, but is it not credible that during that time some bacterium or bacillus hitherto harmlessly parasitic, perhaps, in the blood of lower animals has changed its life habit? In the isolated and sparsely inhabited regions of Tibet, it is possible that for many thousand years the assumed bacterium was never bred in the blood of man; it is possible that when it first found a new host it was comparatively harmless to him, but within a hundred years it may have become so altered by new conditions that it has developed into what is practically a new species. If these theories are relatively true, it is not unlikely that this new bacterium is working out its own destruction by the destruction of its hosts. It may be that it is one of those blind alleys of evolution which reach a certain stage of development and then disappear. But meanwhile what of mankind? We know so little of the history of microscopic life. There is a whole world of evolution in process of which we have no conception, and at this stage, whether my hypothesis be a possible one or not, we are at least sure that an unknown organism animal or vegetable has become visible to us in its effects and may alter the whole history of mankind.

“I lay stress on these aspects, because we are so hide-bound, so restricted, so conventional in our ideas that we assume, without thought, that the process of life as we know of it from a few thousand years of history can never be interrupted. In our few years of individual existence we become accustomed to certain apparent laws of cause and effect, and will not believe that there can be any exception to those assumed laws. But, now, in the face of recent evidence, it is absolutely essential that we should realize instantly and practically that we are threatened with a new factor in life, which imperils the whole human race. It is no longer safe to comfort ourselves with the belief begotten of our vanity that the world was necessarily made for man. It behoves us to take measures for our protection without delay, to undertake our own cause and trust no longer in any beneficent Providence that works always for our ultimate benefit.

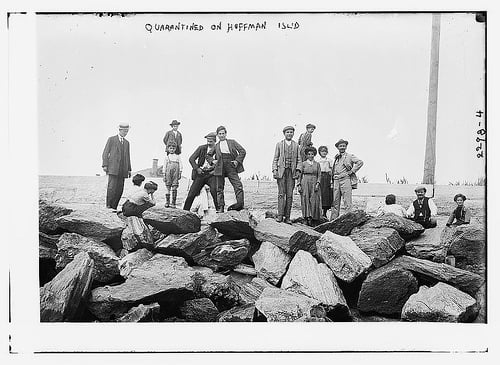

“These measures of protection are clearly indicated. We must close our doors against the invasion of the plague. Quarantine will not protect us; we must have no traffic with Europe until the danger is past. By the happy accident of our position we can become isolated from the rest of the world. We must close our doors before it is too late.”

If the people had not been seriously scared by the sudden irruption of news on the day preceding that on which this article was published, they would have ignored Thrale’s hyperboles or laughed. But, caught in a moment of agitation and fear, a certain section of the crowd took up Thrale’s suggestion, talked about the “closed door,” held meetings, and started propaganda. The Press, with its genius for appreciating and following public opinion, also took up the suggestion, and was automatically divided into two sections, recognizable as Liberal and Conservative.

The Times took command of the situation with a leader, in which Thrale’s argument was pounded, rather than picked, to pieces; but the Daily Mail produced more effect with two special articles contributed, one by a bacteriologist, the other by a professor of economics. The first had little weight — all argument under that head was as yet founded on the most uncertain hypotheses. The second was so convincing that the less ardent supporters of the “closed door” policy were shaken in their convictions.

The writer of the economic article pointed out that an England with closed doors could not feed herself for a month. He was scrupulously fair in his argument, and was at great pains to show that even if preparation was instantly made to lay in large stores of grain from Canada, tinned meats from America, and food-stuffs generally from the many places which were as yet free from any taint of plague, it would still be impossible to provide for more than a three months’ isolation. Then, leaving this aspect of the question, he went on to show in detail that even if the food could be supplied, the practical cessation of our enormous foreign trade would mean the destruction of England’s commerce, and he wound up with an earnest exhortation to the country at large, warning the people to beware of scaremongers, pessimists, and opportunists who had their own ends to serve, and cared nothing for the general welfare. It was an excellent article in every way; quite one of the best that the Daily Mail had ever published. And as this, too, was declared free of any copyright restrictions, it was largely circulated.

The Daily Post replied next morning by pointing out that the celebrated professor of economics was nullifying all his own previous utterances on the case for Tariff Reform, but that retort carried little weight. No one cared if the professor contradicted himself; anyone, except the faddists, could see that the argument of the article was sound, in fact incontrovertible. What had to be done was to put pressure on the Local Government Board. It was true that the Daily Post, the semi-official organ of the Government, affirmed that the Board in question was alert and active, but that announcement was regarded as a cliché; what was wanted were particulars of the preventive measures that were being taken.

The members of the great Gosling family, in offices, warehouses and shops followed the line of least resistance, while making some assertion of their rights as citizens.

George Gosling’s arguments with his crony Flack were excellently representative. “What yer think of this ‘closed door’ business?” asked Flack.

“Goin’ a bit too far, in my opinion,” returned Gosling judicially.

Flack’s natural incredulity had inclined him in the same direction, but his colleague’s certainty swung him round at once.

“I ain’t so sure o’ that,” he said. “Looks to me as things is going pretty bad.”

“Bad enough, I grant you,” returned Gosling. “But there isn’t no need for us to lose our ’eads over it. Take it all round, you know, it’s pretty certain as things isn’t as bad as is made out, whereas, on the other ’and, the ‘closed door’ policy’d mean ruin and starvation for ’undreds of thousands there’s no gettin’ round that.”

“Better a few ’undred thousands than the ’ole male population,” said Flack.

“If it come to that, but it won’t; no fear, not by a long chalk, it won’t,” replied Gosling. “What’s got to be done is to get the Local Government Board to work. We’ve got to ’ave a regular system o’ quarantine established, that’s what we’ve got to ’ave.”

It did, indeed, appear the most practical form of prevention at the moment; it is hard to see what other measures could have been adopted. The supporters of the “closed door” policy soon began to lose adherents. The scheme was obviously alarmist, far-fetched and utterly impracticable….

4

Through February and the early part of March the plague spread through Central Europe, but not with an alarming rapidity.

In the second week of March, Berlin was reporting a weekly roll of over five hundred deaths attributable to this cause, and Vienna was second with between four and five hundred. In St Petersburg and Moscow the figures were no higher, and there were as yet comparatively few cases in France, and none in Spain or Portugal.

Many authorities were of opinion that the mortality had reached the maximum, and that the plague would work itself out in the course of a few more weeks. Moreover it appeared that the early reports of the highly infectious character of the plague must have been grossly exaggerated, for as yet there had been not a single case in the British Isles despite the enormous traffic between England and the Continent. It is true that the strictest quarantine had been established it had been ascertained that the period of gestation of the germ was about fifty hours but not one single case had so far been detained in quarantine ships or hospitals. It was argued from this that the plague was not infectious at all in the ordinary sense, and only mildly contagious; that it flourished in certain centres and was not easily transferable from one centre to another.

The only aspect of the thing that was seriously alarming was the horrible mortality among doctors and the specialists who were endeavouring to recognize and isolate the characteristic germ of the disease. Nine English experts who had dared martyrdom in the cause of science had gone to Berlin to make investigations, and not one of them had returned. As a consequence of this strange susceptibility of the investigator, whether medical man or bacteriologist, there was still an extraordinary ignorance of the general nature and action of the disease.

Nevertheless, despite this one intimidating aspect of the plague, the general attitude in the middle of March was that the quarantine arrangements were enormously impeding trade and should be relaxed. The foreign governments were alive to the seriousness of the scourge, and were doing all in their power to prevent infection. There had been a scare, but people were calm again, now, and able to realize the extent of the earlier exaggerations.

The Government passed the second reading of the English Church Disestablishment Bill by a majority of nineteen, before the Easter recess, and the Goslings, who had grown used to the plague, whose chief attitude towards it was that it was an infernal nuisance which interfered with trade, turned their attention gladly to the new topic; they all thought that a general election at that moment would result in an overwhelming Conservative majority. And as the Liberals had been in power for more than ten years, that eventuality was regarded with complacency.

But at this critical moment — to the joy of the Evangelicals — the new plague set to work in earnest.

VI

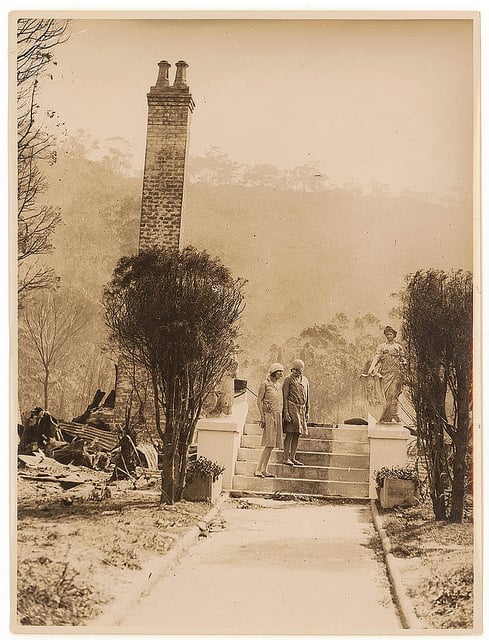

DISASTER

Russia was smitten. Once more communication was cut off from Moscow, this time by a different agent. The work of the city was paralysed. Men were falling dead in the street, and there were only women to bury them. A wholesale emigration had begun. The roads were choked with people on foot and in carriages, for the trains had ceased to run.

The news filtered in by degrees: it was confirmed, contradicted and definitely confirmed again every few hours.

Then came final confirmation, with the news that something approaching war had broken out — a war of defence. Germany had sent troops to the frontier to stem the tide of emigrants from smitten Russia and Poland; and Austria-Hungary was following her example.

Parliament re-assembled before the Easter recess had expired. The time for more drastic measures had come, and the Premier explained to the House that it was proposed to bring in a Bill immediately to cut off communication with Europe.

There can be no doubt that England was now badly scared, but centuries of protection had established a belief in security which was not easily shaken.

The enthusiasts for the “closed door” policy found plenty of recruits, but on the other side there was a solid body of opinion which maintained that the danger was grossly exaggerated. And when the Evening Chronicle came out with a long leader and a backing of expert opinion, to prove that the “Closed Door” Bill — as it was commonly called — was a dodge of the Government’s in order to retain office, a well-marked reaction followed against the last and terrible step of cutting off all communication with Europe; and the Conservative party was joined by some avowed Liberals who had personal interests to consider in this connexion.

In committee-rooms, members of the Opposition were inclined to be jubilant: “If we can throw out the Government on this Bill we shall simply sweep the country… all the manufacturers in the North will be with us… even Scotland, most likely… we should come back with a record majority….”

The prospects were so magnificent that there could be no hesitation in making a party question of the Bill.

No time was to be lost, for the Bill was to be rushed, it was an emergency measure, and it was proposed that it should become law within four days. Preparations were already in hand to carry out the provisions enacted.

An urgent rally of the Opposition was made, and when the Bill came up for the second reading the Premier addressed a well-filled House. The House was not crowded because a large number of people, including many members of Parliament, were on their way to America. All the big liners were packed on their outward voyage and were returning, contrary to all precedent, in ballast — this ballast was exclusively food-stuffs.

The Premier introduced the Bill in a speech which was remarkable for its sincerity and earnestness. He outlined the arrangements that were being made to feed the community, and showed clearly that while communication remained open with America, there was no fear of any serious shortage. Pausing for a moment on this question of intercourse with America, he made a point of the fact that American ports were already closed to emigrants from all European countries with the one exception of Great Britain, and that if a single case of plague were reported in these islands the difficulties of obtaining food-stuffs from America and the Colonies would be enormously increased. He wound up by almost imploring the House not to make a party question of so urgent and necessary a measure at a time when the safety of England was so terribly threatened. He pleaded that at this critical moment, unparalleled in the history of humanity, it was the duty of every man to sink his own personal interests, to be ready to make any sacrifice, for the sake of the community.

Mr Brampton, the leader of the Opposition, then completely destroyed the undoubted effect which had been made upon the House. He did not openly speak in a party spirit, but he hinted very plainly that the Bill under consideration was a mere subterfuge to win votes. He poured contempt upon the fear of the plague, which he characterized throughout as the “Russian epidemic,” and ended with the advice to keep a cool head, to preserve the British spirit of sturdy resistance instead of shutting our doors and bringing the country to commercial ruin. “Are we all cravens,” he concluded, “scurrying like rabbits to our burrows at the first hint of alarm?”

The further debate, although lengthy, had comparatively little influence; the House divided, and the Government was defeated by a majority of nine.

2

The news was all over the country by ten o’clock that night, and it was noticeable that a large percentage of the younger generation still regarded the danger as “rather a lark.” This threat of the plague held a promise of high adventure; youth can only realize the possibility of death in its relation to others.

“I say, if this bally old plague did come…” remarked a young man of twenty-two, who was sitting with a friend in the little private bar of the “Dun Taw” Hotel.

His friend drew his feet up on to the rungs of his tall stool and winked at the barmaid.

“Well, go on. What if it did?” remarked that young woman.

The young man considered for a moment and then said: “Those that got left would have a rare old time.”

“It’s the women as’d get left, seems to me,” replied the barmaid, and scored a point.

“I say, surely you don’t come from this part of the world?” was the compliment evoked by her wit.

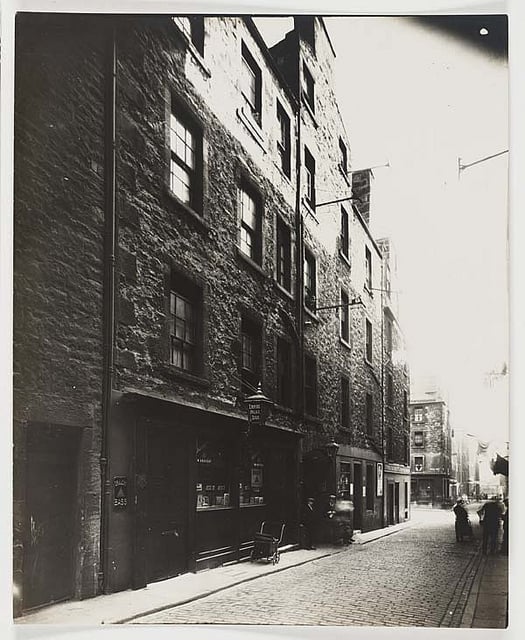

“Not me!” was the answer, “I’m a Londoner, I am. Only started yesterday, and sha’n’t stay long if today’s a fair sample. There ’asn’t been a dozen customers in all day, and they were in such a ’urry to get their tonic and go that I’m sure they couldn’t ’ave told you whether me ’air was black or ches’nut.”

Both men immediately looked at the crown of pretty fair hair which had been so churlishly slighted.

“First thing I noticed about you,” said one.

The other, who had hardly spoken before, took the cigarette out of his mouth and remarked: “You can never get that colour with peroxide.”

The barmaid looked a little suspicious.

“Oh, he means it all right, kid,” put in the younger man quickly. “Dicky’s one of the serious sort. Besides, he’s in that line; travels for a firm of wholesale chemists.”

Dicky nodded gravely. “I could see at once it was natural,” he remarked with the air of an expert.

“Ah! you’re one of them that keeps their eyes open,” returned the barmaid approvingly, and Dicky modestly acknowledged the compliment by saying that his business necessitated close observation.

“Most men are as blind as bats,” continued the barmaid, and the examples she gave from her own experience led to an absorbing conversation, which was presently interrupted by the shriek of the swing door.

The newcomer was a small, fair man with a neatly waxed moustache. He came up to the counter with the air of an habitué, and remarked, “Hallo! where’s Cis? You’re new here, aren’t you?”

The barmaid, recognizing the marks of a regular customer, quietly admitted that this was only her second day at the “Dun Taw.”

“I’ve been away for two months,” explained the fair man, and ordered “Scotch.” He was evidently in the mood for company, for he brought up a stool and, sitting a little way back from the bar, he began to address his three hearers at large.

“Only came back from Europe this evening,” he said, “and glad to be home, I assure you.” He raised his left hand with a gesture intended to convey horror, and drank half his whisky at a gulp.

Dicky turned to give his serious attention to the narrative which was plainly to follow, and somewhat ostentatiously observed the details of the newcomer’s dress. Dicky had a new-found reputation to maintain. His friend looked bored and a little sulky, and tried to continue his conversation with the barmaid, but that young woman, appreciating the difference in value between a casual and a regular customer, passed a broad hint by with a smile and said: “Europe? Just fancy!”

“It’s a place to get out of, I assure you,” said the fair man. “I’ve been over there for two months Germany and Austria chiefly but for the last fortnight I’ve been wasting my time. There’s nothing doing.”

“Isn’t there?” commented Dicky with great seriousness.

“Oh, we’re sick to death of this bally plague,” put in the other young man quickly. “There’s been simply nothing else in the papers for the last I don’t know how long. I want to forget it.”

The fair man reached forward and put down his empty glass on the bar counter. “Same again, Miss,” he said, and then: “We’ll all be more sick of the plague before we’ve finished with it. It’s a terror. If I was to tell you a few of the things I’ve seen in the past fortnight, I don’t suppose you’d believe me.”

“That’s all right; I’d believe you quick enough,” returned the young man. “Point is, what’s the good of getting yourself in a funk about it? Personally I don’t believe it’s coming to England. If it was it would have been here before this. What I say is…”

His pronouncement of opinion ceased abruptly. The fair man’s behaviour riveted attention. He was gazing past the barmaid at the orderly rows of shining glasses and various shaped bottles behind her. His mouth was open. He gazed intensely, horribly.

The barmaid backed nervously and looked over her shoulder. The two young men hastily rose and pushed back their stools. The same thought was in all their minds. This neat, fair man was on the verge of delirium tremens.

In a moment the air of intercourse and joviality that had pervaded the little room was dissipated; in place of it had come shocked surprise and fear.

There was an interval of slow desolating silence, and then the convulsive grip of the fair man shattered the glass he held, and the fragments fell tinkling to the floor.

“I say, what’s up?” stammered the barmaid’s admirer, while the barmaid herself shrank back against the shelves and watched nervously. She had had experience.

The fair man’s head was being pulled slowly backwards by some invisible force. His eyes, staring straight before him, appeared to watch with fierce intensity some point that moved steadily up the wall of shelves behind the counter; up till it reached the ceiling and began to move over the ceiling toward him.

Then, quite suddenly, the horrible tension was relaxed; his head fell loosely forward and he clapped both hands to the nape of his neck. He was breathing loudly in short quick gasps.

“I say, do you think he’s ill?” asked the young man. At the suggestion Dicky made a step towards the sufferer; his knowledge of chemistry gave him a professional air.

“He’s come from Europe…. Suppose it’s the plague,” whispered the barmaid.

And at that the two young men started back. As the words were spoken realization swept upon them.

Mumbling something about “get a doctor,” they rushed for the door. One of them made a wide detour — he had to pass the man who sat doubled forward in his chair, frantically gripping the base of his skull.

Hardly had the clatter of the swing door subsided before he fell forward on to the floor. He was groaning now, groaning detestably. The barmaid whimpered and stared.

“Women don’t get it,” she said aloud. But she kept to her own side of the counter.

Later the owner of the “Dun Taw” identified the fair man from a distance as Mr Stewart, of the firm of Barker and Prince.

RADIUM AGE SCIENCE FICTION: “Radium Age” is HILOBROW’s name for the 1904–33 era, which saw the discovery of radioactivity, the revelation that matter itself is constantly in movement — a fitting metaphor for the first decades of the 20th century, during which old scientific, religious, political, and social certainties were shattered. This era also saw the publication of genre-shattering writing by Edgar Rice Burroughs, Sax Rohmer, E.E. “Doc” Smith, Jack London, Arthur Conan Doyle, Aldous Huxley, Olaf Stapledon, Karel Čapek, H.P. Lovecraft, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Yevgeny Zamyatin, Philip Gordon Wylie, and other pioneers of post-Verne/Wells, pre-Golden Age “science fiction.” More info here.

HILOBOOKS: The mission of HiLoBooks is to serialize novels on HiLobrow; and also, as of 2012, operating as an imprint of Richard Nash’s Cursor, to reissue Radium Age science fiction in beautiful new print editions. So far, we have published Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague, Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”), Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt, H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook, Edward Shanks’s The People of the Ruins, William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land, and J.D. Beresford’s Goslings. Forthcoming: E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man, Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage, and Muriel Jaeger’s The Man with Six Senses. For more information, visit the HiLoBooks homepage.

SERIALIZED BY HILOBOOKS: Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague | Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”) | Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt | H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook | Edward Shanks’ The People of the Ruins | William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land | J.D. Beresford’s Goslings | E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man | Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage | Muriel Jaeger’s The Man With Six Senses | Jack London’s “The Red One” | Philip Francis Nowlan’s Armageddon 2419 A.D. | Homer Eon Flint’s The Devolutionist | W.E.B. DuBois’s “The Comet” | Edgar Rice Burroughs’s The Moon Men | Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s Herland | Sax Rohmer’s “The Zayat Kiss” | Eimar O’Duffy’s King Goshawk and the Birds | Frances Hodgson Burnett’s The Lost Prince | Morley Roberts’s The Fugitives | Helen MacInnes’s The Unconquerable | Geoffrey Household’s Watcher in the Shadows | William Haggard’s The High Wire | Hammond Innes’s Air Bridge | James Branch Cabell’s Jurgen | John Buchan’s “No Man’s Land” | John Russell’s “The Fourth Man” | E.M. Forster’s “The Machine Stops” | John Buchan’s Huntingtower | Arthur Conan Doyle’s When the World Screamed | Victor Bridges’ A Rogue By Compulsion | Jack London’s The Iron Heel | H. De Vere Stacpoole’s The Man Who Lost Himself | P.G. Wodehouse’s Leave It to Psmith | Richard Connell’s “The Most Dangerous Game” | Houdini and Lovecraft’s “Imprisoned with the Pharaohs” | Arthur Conan Doyle’s “The Sussex Vampire.”

ORIGINAL FICTION: HILOBROW has serialized three novels: James Parker’s The Ballad of Cocky The Fox (“a proof-of-concept that serialization can work on the Internet” — The Atlantic); Karinne Keithley Syers’s Linda Linda Linda (which includes original music); and Robert Waldron’s roman à clef The School on the Fens. We also publish original stories and comics. These include: Matthew Battles’s stories “Gita Nova“, “Makes the Man,” “Imago,” “Camera Lucida,” “A Simple Message”, “Children of the Volcano”, “The Gnomon”, “Billable Memories”, “For Provisional Description of Superficial Features”, “The Dogs in the Trees”, “The Sovereignties of Invention”, and “Survivor: The Island of Dr. Moreau”; several of these later appeared in the collection The Sovereignties of Invention | Peggy Nelson’s “Mood Indigo“, “Top Kill Fail“, and “Mercerism” | Annalee Newitz’s “The Great Oxygen Race” | Flourish Klink’s Star Trek fanfic “Conference Comms” | Charlie Mitchell’s “A Fantasy Land” | Charlie Mitchell’s “Sentinels” | Joshua Glenn’s “The Lawless One”, and the mashup story “Zarathustra vs. Swamp Thing” | Adam McGovern and Paolo Leandri’s Idoru Jones comics | John Holbo’s “Sugarplum Squeampunk” | “Another Corporate Death” (1) and “Another Corporate Death” (2) by Mike Fleisch | Kathryn Kuitenbrouwer and Frank Fiorentino’s graphic novel “The Song of Otto” (excerpt) | John Holbo’s graphic novel On Beyond Zarathustra (excerpt) | “Manoj” and “Josh” by Vijay Balakrishnan | “Verge” by Chris Rossi, and his audio novel Low Priority Hero | EPIC WINS: THE ILIAD (1.408-415) by Flourish Klink | EPIC WINS: THE KALEVALA (3.1-278) by James Parker | EPIC WINS: THE ARGONAUTICA (2.815-834) by Joshua Glenn | EPIC WINS: THE MYTH OF THE ELK by Matthew Battles | TROUBLED SUPERHUMAN CONTEST: Charles Pappas, “The Law” | CATASTROPHE CONTEST: Timothy Raymond, “Hem and the Flood” | TELEPATHY CONTEST: Rachel Ellis Adams, “Fatima, Can You Hear Me?” | OIL SPILL CONTEST: A.E. Smith, “Sound Thinking | LITTLE NEMO CAPTION CONTEST: Joe Lyons, “Necronomicon” | SPOOKY-KOOKY CONTEST: Tucker Cummings, “Well Marbled” | INVENT-A-HERO CONTEST: TG Gibbon, “The Firefly” | FANFICTION CONTEST: Lyette Mercier’s “Sex and the Single Superhero”