Paleo Gifs

By:

September 26, 2012

In the what’s old is new again department, archaeologist Marc Azéma of the University of Toulouse-Le Mirail and artist Florent Rivère propose the idea that cave art contains: animated gifs.

Lascaux is the cave with the greatest number of cases of split-action movement by superimposition of successive images. Some 20 animals, principally horses, have the head, legs or tail multiplied. When the paintings are viewed by flickering torchlight, the animated effect “achieves its full impact,” said Azéma.

The technique of onion-skinning is familiar to today’s animators. Originally referring to a type of super-fine tracing paper used to draw the next image in an animation sequence, it has been built as a tool into many computer animation programs. By seeing the previous drawing lightly greyed out in a layer “under” the current drawing, the artist can see how far to move the leg, or blink the eye, to create a realistic illusion. When a sequence of drawings have been completed, overlaying all the layers superimposes an idea of motion. When they flicker in sequence, persistence of vision means the rabbit will run.

Taking it to the next level, researchers speculate that, instead of two heads and eight legs using superimposition to suggest motion, the flicker from firelight actually animated the drawings into gifs. The video below shows how this might work:

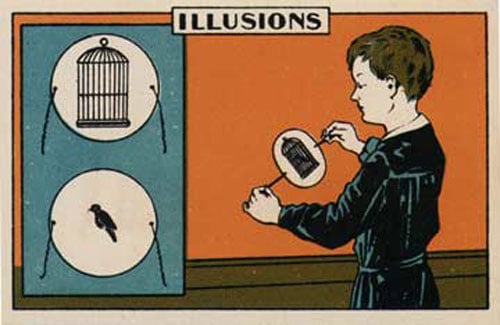

Azéma and Rivère also have a theory about bone discs previously thought to be pendants, or perhaps prehistoric fashion buttons. The discs are similar in form to the Victorian toys known as thaumatropes, a type of pre-book flip book, in which a string or stick threaded through two holes allows the disc to be spun, creating a simple animation out of the two-sided drawing.

They mentioned one of the most convincing cases, a bone disc found in 1868 in the Dordogne. On one side, the disc features a standing doe or a chamois. On the other side, the animal is lying down. Azéma and Rivère discovered if a string was threaded through the central hole and then stretched tight to make the disc rotate about its lateral axis, the result was a superimposition of the two pictures on the retina.

Is this what cave artists actually intended, and is it what they actually saw? There’s probably no way to know definitively, although the hypothesis makes an intriguing companion for Werner Herzog’s 3D documentary of Chauvet Cave, Cave of Forgotten Dreams, which appeared to demonstrate the sophisticated anamorphic properties of cave art.

But as every artist knows, even if an effect is not initially intended, it may still very well be there.