The People of the Ruins (14)

By:

August 23, 2012

HILOBROW is pleased to present the fourteenth installment of our serialization of Edward Shanks’ The People of the Ruins: A Story of the English Revolution and After. New installments will appear each Thursday for 16 weeks.

Trapped in a London laboratory during a worker uprising in 1924, ex-artillery officer and physics instructor Jeremy Tuft awakens 150 years later — in a neo-medieval society whose inhabitants have forgotten how to build or operate machinery. Not only have his fellow Londoners forgotten most of what humankind used to know, before civilization collapsed, but they don’t particularly care to re-learn any of it. Though he is at first disconcerted by the failure of his own era’s smug doctrine of Progress, Tuft eventually decides that post-civilized life is simpler, more peaceful. That is, until northern English and Welsh tribes threaten London — at which point he sets about reinventing weapons of mass destruction.

Shanks’ post-apocalyptic novel, a pessimistic satire on Wellsian techno-utopian novels, was first published in 1920. In October, HiLoBooks will publish a beautiful new edition of The People of the Ruins, with an introduction by Tom Hodgkinson.

SUBSCRIBE to HILOBROW’s serialized fiction via RSS.

LAST WEEK: “‘No!’ the Speaker wailed in a thin and inhuman voice. ‘No! Those white flags are ours: I saw them raised. Thomas Wells has betrayed us. He has sold us to the Welsh.’ He let his arms fall by his sides and stood there limp, lax, shrunken, hopeless.”

ALL EXCERPTS: 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 |15 |16

CHAOS

The awaking was sudden and disconcerting. Without any interval, it seemed, Jeremy found himself staring up at the blinding sky, which looked almost white with the dry heat, and suffering miserably from an intolerable weight on his throat. This, he soon perceived, was caused by the legs of a dead man, and after a moment he threw them off and sat up, licking dry lips with a dry tongue. His ears still sang a little and he felt sick; but his head was clear, if his mind was still feeble. A minute’s reflection restored to him all that had happened, and he looked around him with slightly greater interest.

He alone in the gun-pit seemed to be alive, though bodies sprawled everywhere in twisted and horrible attitudes. A few yards away lay Jabez, stabbed and dead, clinging round the trail of a gun, his nutcracker face grinning fixedly in a hideous counterfeit of life. Jeremy was unmoved and let his eyes travel vaguely further. He was very thirsty and wanted water badly. But apart from this desire he was little stirred to take up the task of living again. What he most wanted, on the whole, was to lie down where he was and doze, to let things happen as they would. The muscles of his back involuntarily relaxed and he subsided on to one elbow, yawning with a faint shudder. Then he realized that he would not be comfortable until he had drunk; and he rose stiffly to his feet. Close by the wheel of one of the guns, just inside it, stood an open earthenware jar half full of water, miraculously untouched by the tumult that had raged in the battery. Jeremy did not know for what purpose the gunners had used it, and found it blackened with powder and tainted with oil; but it served to quench his thirst. He drank deeply and then again examined the scene of quiet desolation.

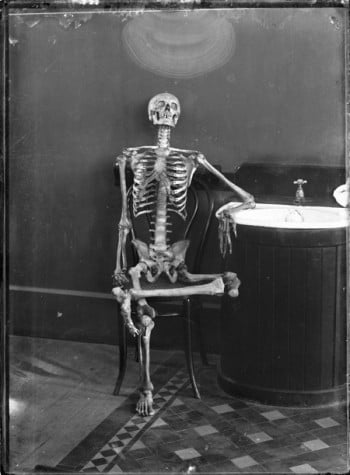

One by one he identified the bodies of all the members of the gun-crews: none had escaped. Some had been bayonetted, some clubbed, some strangled or suffocated under the weight of their assailants. The feeble lives of a few, perhaps, had merely flickered out before the terror of the onset. Jeremy mused idly on the fact that all these ancients, who, if ever man did, deserved a quiet death, should have perished thus violently together, contending with a younger generation. He wondered if they would be the last gunners the world was to see. He found it odd that he, the oldest of all, should be the last to survive. He felt again the loneliness that had overtaken him — how long ago?— in the empty Whitechapel Meadows, when once before he had emerged from darkness. But now he suffered neither bewilderment nor despair. It was thus that fate was accustomed to deal with him, and something had destroyed or deadened the human nerve that rebels against an evil fate.

He sank on to the ground in a squatting position, propped his back against a wheel of the nearer gun and rested his chin on his hands, speculating, as though on something infinitely remote, on the causes and circumstances of his ruin. Thomas Wells, he supposed, had, in fact, sold them to the President of Wales, had very likely been corrupting the army for days before the battle. By that treachery the campaign was irrevocably lost and, Jeremy told himself calmly, the whole kingdom as well. There was no army between this and London, nor could any now be raised in the south. England was at the mercy of the invaders, and the reign of the Speakers was for ever finished. It was over, Jeremy murmured, with the death of their last descendant — for he took it for granted that the old man had been killed.

And then a sudden inexplicable wave of anger and foreboding came over him, as though the deadened nerve had begun to stir again and had waked him from this unnatural indifference. He scrambled to his feet and stared wildly in the direction of London. He must go there and find the Lady Eva. He found that he still desired to live.

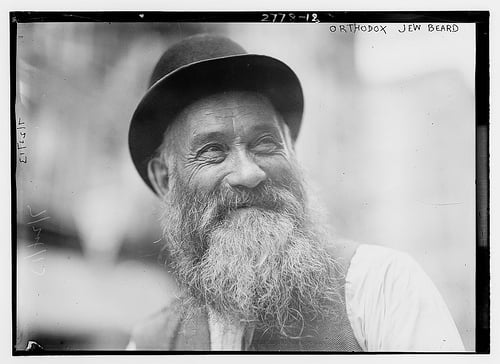

With the new desire came activity of body and mind. He must travel as fast as he could, making his way through the ranks of the invaders and more quickly than they, and to do this with any chance of success he needed weapons. He would trust to luck to provide him with a horse later on. His own pistols had disappeared, but he began a determined and callous search among the dead. As he hunted here and there his glance was attracted by something white and trailing in the heap of bodies which lay between the wheels of the other gun. He realized with a shock that it was the Speaker’s long beard, somehow caught up between two corpses which hid the rest of him. He looked at it and hesitated. Then, muttering, “Poor old chap!” he interrupted his search to show his late master what respect he could by composing his dead limbs. But as he pulled the old man’s body free, the heavy, pouched eyelids flickered, the black lips parted and emitted a faint sigh. In an instant Jeremy had fetched the jar of water, and after sucking at it languidly like a sick child, the Speaker murmured something that Jeremy could not catch.

“Don’t try to talk,” he warned. “Be quiet for a moment.”

“Is it all over?” the Speaker repeated in a distinct but toneless voice.

“All over,” Jeremy fold him; and in his own ears the words rang like two strokes of a resonant and mournful bell.

“Then why are we here?”

Jeremy explained what had happened, and while he told the story the Speaker appeared, without moving, slowly to recover full consciousness. When it was done he tried to stand up. Jeremy helped him and steadied him when he was erect.

“It is all over,” he pronounced in the same unwavering voice. Then he added with childish simplicity, “What shall we do now?”

“Get away from here,” Jeremy cried with a sudden access of terror. “Thomas Wells will want to make sure we are dead, and this is just where he will look for us — he may come back any minute! And we mustn’t be caught; we must get to London, to help the Lady Eva!”

“Get away from here. Very well, I am ready.” And with a slow unsteady movement the Speaker began to pick his way across the battery, lurching a little when he turned aside to avoid a body lying at his feet. Jeremy ran after him and offered his arm, which the old man docilely accepted. When they had climbed out of the pit they saw that not only the village of Slough was burning, but also that every building for miles around seemed to have been fired. On the main road, away to their left, Jeremy distinguished a long column of wagons and mounted men on the march, accompanied by irregular and straggling crowds — the transport and the camp-followers, he surmised. But already most of the invaders were far ahead, making for London and, eager for that rich prize, not staying to loot the poor farmhouses, the smoke of which indicated their advance.

Jeremy turned and looked at his companion. The old Jew had paused without a word when Jeremy paused and stood waiting patiently for the order to move again. A sort of enduring tranquillity had descended like a thin mask on the savage power of his face, softening all its features without concealing them. His eyes shone softly with a peaceful and unnatural light. He stared fixedly straight before him, and what he saw moved him neither to speech nor to a change of expression. Jeremy regarded him with doubt, which deepened into fear. This passivity in one who had been so vehement had about it something alarming. The old man must have gone mad.

Jeremy shuddered at the suggestion. His thoughts suddenly became unrestrained, ridiculous, inconsequent. It was wicked to have led them into this misery and then to avoid reproach by losing his reason! How was he to get a madman over the difficult road to London? He felt as if he had been deserted in a hostile country with no companion but a hideous, an irritating monstrosity… That fixed, gentle smile began to work on his nerves and to enrage him. It was a symbol of an unreasonable and pitiless world, where the sun shone and the birds sang, and which yet turned wantonly to blast his most beautiful hopes. He cursed at the old man, cried, “It was all your fault, this!” madly raised his hand to strike — But the Speaker turned on him with a regard so quiet and so melancholy that he drew back in horror from his own intention.

“Come on, sir,” he said with hoarse tenderness. “Give me your arm. We must keep to the right, well away from the road. We’ll get through somehow.”

Darkness was fast thickening in the air when Jeremy and the Speaker at last reached the western edge of London. During that tortuous and incredible journey the old man had not more than once or twice been shaken out of his smiling calm. He had walked or ridden, stood motionless as a stone by the roadside or crouched in hiding in the ditch, as Jeremy bade him, obedient in all things, impassive, apparently without will or desire of his own. Jeremy bore for them both the burden of their dangers and their escape, planned and acted and dragged his companion after him, astonishing himself by his inexhaustible reserve of vitality and resolution. Or, rather, he did none of these things, but some intelligence not his own reigned in his mind, looked ahead, judged coolly, decided, and drove his flagging body to the last limits of fatigue. An ancient instinct woke in the depths of his nature and took the reins. He was not at all a man, a lover, Jeremy Tuft, scientist, gunner, revenant, struggling, by means of such knowledge and gifts as his years of conscious life had bestowed on him, across difficult obstacles to reach a desired goal. He was a blind activity, a force governed by some obscure tropism; the end called, and like an insect or a migrating bird he must go to it, whether he would or not, whatever might stand in the way.

Once, when they almost stumbled on a ranging party of the President’s horsemen, Jeremy pulled the Speaker roughly after him into a pond and found a hiding-place for them both among the thick boughs of an overhanging tree. When the old man felt the water rising coldly to his armpits he uttered a single faint cry of distress or despair, and Jeremy scanned him keenly, wondering whether perhaps it would not be better to desert that outworn body and altered brain as too much encumbrance on his flight. Afterwards, when the danger had gone by and it was time to emerge, they found that they had sunk deep in the mud. Jeremy’s expression did not change or his heart beat a stroke the faster during the three or four minutes in which he struggled to draw himself up into the tree. Then he gazed down pitilessly on his companion, considering; but, seeing no signs of agitation or indocility on that dumb immobile mask, at last after much effort he drew him out.

Once they came sharply around a corner and saw ahead of them one of the Welsh troopers leading a riderless horse. It was too late to look for cover or to escape, and Jeremy, halting the Speaker by a rude jerk of his arm, went forward with an air of calm. As he came closer he cried out to the soldier in a raspingly authoritative voice: “I am looking for Thomas Wells. You must lead me to Thomas Wells at once.”

The man, dark, squat, low-browed and brutish, paused and hesitated. He was puzzled by the unfamiliar speech of the eastern counties and was ignorant whether this might not be one of the deserters from the Speaker’s army whom he ought to receive as a comrade. His uncertainty lasted long enough for Jeremy to come close to him, to produce a bayonet taken from one of the dead, and to drive it with a single unfaltering movement into his heart. He toppled off the horse without a sound, leaving one foot caught in the stirrup. Jeremy disentangled it, took the man’s pistol and cloak, and rolled the body into the ditch, where he put a couple of dry branches over it. Then he beckoned to the Speaker to come up and mount. Thereafter they traveled more rapidly.

They had gone by such by-ways as to avoid for the most part the main track of the invading army, but they saw bands of marauders here and there and more often the evidences of their passage. As they came closer to London, in the neighborhood of Fulham, they slipped miraculously unchallenged through the advanced guard. Here Jeremy saw with a clear eye horrors which affected him no more than the faces of other people affect a hurrying man who jostles impatiently against them in a crowded street. The flare of burning cottages lit up the gathering twilight, and there were passing scenes of brutality… The invaders were pressing on to reach the city by nightfall and had no time to be exhaustively atrocious. But Jeremy heard (and was not detracted by it) the screams of tortured men, women, and children, and sometimes of cattle. Beyond the furthest patrols of the army they found the roads full of fugitives, hastening pitifully onward, though the country held for them no refuge from this ravening host, unless it might be in mere chance. These, like their pursuers, were but so many obstacles in the way which Jeremy and the Speaker had to pass by as best they could.

When they came to the first cluster of houses it was dark and the full moon had not yet risen; but in front of them great welling fountains of fire softly yet fiercely illuminated the night sky.

“The people have gone mad,” Jeremy muttered with cold understanding. “They are plundering the city before the enemy can plunder it. Come on, we must hurry.” He urged forward the Speaker’s horse and they plunged together into that doubtful flame-lit chaos.

No man raised a hand to stay them as they passed. The streets were crowded with hurrying people, both men and women, among whom it was impossible to distinguish which were escaping and which were looting. All carried bundles of incongruous goods and all looked fiercely yet shrinkingly at any who approached them. Many were armed, some with swords, some with clubs, some with the rudest weapons, odd pieces of iron or the legs of chairs, which they brandished menacingly, prepared to strike on the smallest suspicion rather than be unexpectedly struck down. Here and there in the boiling mob Jeremy distinguished the sinister, degraded faces, the rude, bundled clothes, of the squatters from the outskirts. Without slackening his pace he glanced around at the Speaker, who was moving through the turmoil with gentle smile and fixed, unseeing eyes. The time was already gone when he might have been affected by the agony of his city.

Out of the raging inferno of Piccadilly, where already a dozen houses were on fire, they turned down a dark and narrow lane behind two high walls, and as they did so the noise of the tumult became strangely remote, as though it belonged to another world. Here there was no sound save the terrifying reverberations caused by their horses’ hoofs. At the bottom of it was a gate set in the boundary wall of the gardens of the Treasury. It stood wide open, and inside there was a mysterious and quiet blackness. They rode through and immediately drew rein.

Then the sense of these invisible but familiar walks and lawns quickened Jeremy’s cold resolution to an intolerable agony of pain — pain like that which follows the thawing of a frozen limb. During the wild and hasty journey the only conscious thought that had possessed him had been that somehow or other he must get to the Treasury. It had excluded all consideration of what he might find, or what he should do when he got there. Now suddenly he understood that this place and all the people in it had been existing and changing, as places and people change, in reality as well as in his mind, that things had been happening here in his absence, all that week, all that day, during the time he lay unconscious in the gunpit, during the last hour… It was as though he had carried somewhere in his brain, unalterable till now by any certainty, a picture of the Treasury as it had always been; this black and silent wilderness substituted itself with a shock like a cataclysm. For the first time Jeremy made a sound, a low choked groan of extreme anguish. Then, cold as he had been before, he dismounted and bade the Speaker stay by the horses, because the gardens here were too much broken up for riding at night. He hastened forward alone, staring through the darkness at the empty place where the lights of the Treasury ought to have been.

But there was no light in any of the windows, and Jeremy stumbled on, sinking to the ankles in the soft earth of flower-beds, catching his feet in trailing plants, running headlong into bushes, growing desperate and breathless. Suddenly he became aware of the building, a great vague mass looming over him like a thicker piece of night; and as he stared up at it, it seemed to grow more distinct and the windows glimmered a little paler than the darkness around them. He crawled cautiously along the wall, found a door, which, like the garden-gate, was wide open, and slipped into the chilling obscurity of a passage. Then he paused, hesitating, frightened by the uncanny silence and emptiness of the house.

It was plain that the Treasury had been deserted, though how and why he could not conjecture. He stayed by the door and rested his body against the wall, racking his wits to think what the Lady Eva and her mother might have been expected to do when the news of the disaster reached them — as it must have reached them. He now perceived his own weariness and that he was aching in every member. His head was whirling, perhaps from the delayed effects of the blow that had stunned him, and he felt as though he were flying, swooping up and down in great dizzy circles. His back was an aching misery that in no attitude could find rest. This last check, at what had been for hours and through incredible adventures his only imagined goal, sapped at a blow his unnatural endurance, and for a moment he was ready to fall where he stood and weep in despair.

It was to choke back the tears he felt rising in his throat that he called out, foolishly, in a weak and hoarse voice: “Eva! Where are you? Eva!”

Then most incredibly from the bushes in the garden a few yards behind him came a wavering low cry, “Jeremy, is it you?” and then, in an accent of terror, “Oh, who is it?” At the same time he saw a shadow moving, and the next moment that shadow was in his arms, crying softly, while he held her in a firm embrace.

Some minutes passed thus before the Lady Eva recovered her power of speech. Jeremy lost all sense of time and of events. He wanted first to comfort her and next to know what she had suffered. He had forgotten that he had come to take her away from impending danger.

At last her sobbing stopped and she murmured, her face still close against his breast: “Jeremy, mother is dead!”

“Dead!” They both spoke in whispers, as though the silent gardens were full of enemies seeking for them.

“Yes, dead.” She straightened herself and withdrew from his arms, as though she must be free before she could tell her story. Then she went on in a low, hurried, unemphasized voice: “Roger — you know, Roger Vaile — brought the news that… that you had been defeated. He was with Thomas Wells and saw him give the signal to surrender, but he managed to get away, and when he realized it was all over he came straight here. He was badly wounded, I think — he stumbled and fell against me, and my dress is all covered with blood…” She stopped and caught her breath, then went on more firmly: “He was telling us and begging us to go away and hide, and we didn’t want to go. Then a crowd of people came into our room — servants, most of them, grooms and stablemen — and told us that everything was over, that there was no more government, and we had to get out at once, because the Treasury belonged to them now. And I said we’d go, but mother said out loud: ‘Then I must get my jewels first.’

“They got very excited at that, and when she went to her chest to get them, they went after her and pulled her away, not roughly really, and began rummaging in the chest themselves. Roger was standing, holding on to a chair, looking horribly white, and he told mother to come away and leave them. But she wouldn’t; she went back to the chest and ordered them out of the room. They pushed her away again more roughly and laughed at her, and she lost her temper — you know how she used to?— and hit one of them in the face. Then he — then he killed her… with a sword…”

Her voice trailed away into silence. Jeremy took her cold hands and muttered brokenly. “Dearest — dearest —”

“When that happened,” she went on in the same even whisper, “Roger called out to me to run away. He’d got a great bandage around his wound, and he looked so ill I thought he was going to faint. But he stood in the door and drew his knife to keep them from coming after me: I was just outside in the passage. I couldn’t run away. Then one of them came at him, and Roger struck at him with the knife. The man just caught Roger’s wrist and held it for a minute —Roger was so weak — and then pushed him, and he fell down in the passage, and blood came pouring out of his side. Then I—I think he died. And I ran away. I don’t think they came after me… I don’t think they did…”

She was silent again, and Jeremy took her into his arms in an inarticulate agony. She lay there limp and unresponsive. At last she whispered: “I ought to have stayed and looked after him… but I think he was dead. Such a lot of blood came out of his wound… it poured and poured over the floor… it came almost to my feet…”

“Eva!” said Jeremy, and could say nothing more. Several minutes passed before he exclaimed: “It doesn’t matter. We must get away. You must try and forget it all, beloved. I’ll look after you now.”

“I will, oh, I will!” she cried, clinging to him. “But I can’t now —I can see it all the time. I’m trying. And, Jeremy,” she went on, holding him as he tried to draw her away, “afterwards, when I thought they’d gone, I went back… I went back to my room —”

“Yes, dear.” Jeremy was still trying to draw her away.

“And I got this — look!” Jeremy peered at something she held up to him, but could not make out what it was. She thrust it into his hand, and he felt a small round metal box, the size and shape of half an egg. “I took it once, months ago, from that silly girl, Mary. She was pretending to be in love, and she said that if ever her lover deserted her she’d kill herself. Then she boasted that she’d got poison so as to be ready —Rose told me. So I made her give it to me, and I never thought about it again till to-day.”

“Yes, dear,” Jeremy murmured soothingly, “but it’s all right now. You don’t need it. Shall we throw it away?”

“No, no!” she cried agitatedly, snatching the box back; then calmly again: “Don’t be angry with me, Jeremy. It’s stupid, but you don’t know how I wanted that box this afternoon while I was hiding in the garden, so as to be sure… And I couldn’t get up the courage to go back and look for it. I must keep it for a little while now. I’ll throw it away myself in a little while.” She tucked the box into her dress and gave him her hand. Without another word they set off towards the Speaker and the horses.

NEXT WEEK: “Jeremy had just seated Eva on one horse and the Speaker on the other and was preparing to lead them out, when they heard the clatter of hoofs coming furiously down Whitehall, rising loud and clear above the confused sounds that filled the air.”

RADIUM AGE SCIENCE FICTION: “Radium Age” is HILOBROW’s name for the 1904–33 era, which saw the discovery of radioactivity, the revelation that matter itself is constantly in movement — a fitting metaphor for the first decades of the 20th century, during which old scientific, religious, political, and social certainties were shattered. This era also saw the publication of genre-shattering writing by Edgar Rice Burroughs, Sax Rohmer, E.E. “Doc” Smith, Jack London, Arthur Conan Doyle, Aldous Huxley, Olaf Stapledon, Karel Čapek, H.P. Lovecraft, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Yevgeny Zamyatin, Philip Gordon Wylie, and other pioneers of post-Verne/Wells, pre-Golden Age “science fiction.” More info here.

HILOBOOKS: The mission of HiLoBooks is to serialize novels on HiLobrow; and also, as of 2012, operating as an imprint of Richard Nash’s Cursor, to reissue Radium Age science fiction in beautiful new print editions. So far, we have published Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague, Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”), Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt, H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook, Edward Shanks’s The People of the Ruins, William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land, and J.D. Beresford’s Goslings. Forthcoming: E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man, Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage, and Muriel Jaeger’s The Man with Six Senses. For more information, visit the HiLoBooks homepage.

READ: Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague, serialized between January and April 2012; Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”), serialized between March and June 2012; Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt, serialized between April and July 2012; and H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook, serialized between March and August 2012.

ORIGINAL FICTION: HILOBROW has serialized three novels: James Parker’s The Ballad of Cocky The Fox (“a proof-of-concept that serialization can work on the Internet” — The Atlantic) and Karinne Keithley Syers’s Linda Linda Linda. We also publish original stories and comics.