The People of the Ruins (11)

By:

August 2, 2012

HILOBROW is pleased to present the tenth installment of our serialization of Edward Shanks’ The People of the Ruins: A Story of the English Revolution and After. New installments will appear each Thursday for 16 weeks.

Trapped in a London laboratory during a worker uprising in 1924, ex-artillery officer and physics instructor Jeremy Tuft awakens 150 years later — in a neo-medieval society whose inhabitants have forgotten how to build or operate machinery. Not only have his fellow Londoners forgotten most of what humankind used to know, before civilization collapsed, but they don’t particularly care to re-learn any of it. Though he is at first disconcerted by the failure of his own era’s smug doctrine of Progress, Tuft eventually decides that post-civilized life is simpler, more peaceful. That is, until northern English and Welsh tribes threaten London — at which point he sets about reinventing weapons of mass destruction.

Shanks’ post-apocalyptic novel, a pessimistic satire on Wellsian techno-utopian novels, was first published in 1920. In October, HiLoBooks will publish a beautiful new edition of The People of the Ruins, with an introduction by Tom Hodgkinson.

SUBSCRIBE to HILOBROW’s serialized fiction via RSS.

LAST WEEK: “‘Got their ammunition!’ he screamed, the tears pouring down his face. ‘There must have been a lot!’ He reached out blindly for Jabez; and the old men of the battery observed their commander and his lieutenant clasping one another by the hands and leaping madly round and round in an improvised and frenzied dance of jubilation.”

ALL EXCERPTS: 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 |15 |16

TRIUMPH

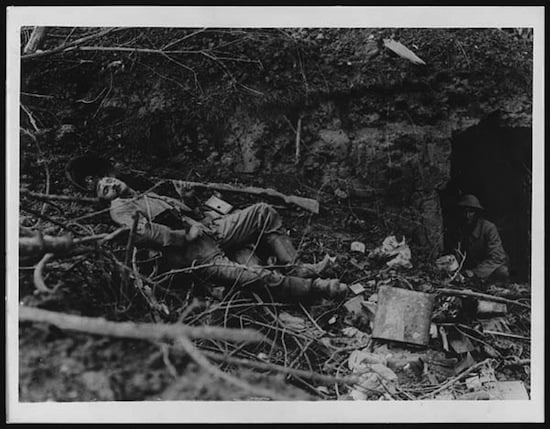

The brief remainder of the battle was for Jeremy a confused and violent phantasmagoria. Immediately on the heels of that triumphant shout he ordered the guns to be brought forward again and had the luck to plump a single shell into a body of the enemies’ reserves before they finally melted out of existence. After that he could not find another mark to fire at. The northern army, struck down in the moment of victory by an overwhelming panic, crumbled all along its line and broke up into flying knots of terrified men, who were surrounded and harried by the jubilant and suddenly blood-thirsty troops of the Speaker. When he perceived this, Jeremy was overcome by a rush of blood to the head.

“We’ve done it! We’ve done it!” he muttered in a dazed way. And then this stupefaction was replaced by a wild and reckless delight. “Come on, Jabez!” he yelled, pounding with his heels the long-suffering horse. “Come on! We’ve got to see this!” Again they were off together, this time leaving the guns behind. Jabez, exalted to an activity wholly unsuited to his years, flung up and down at the stirrup, while Jeremy waved his whip in the air and shouted incoherently. Before they knew it they had shot into the rearmost of the scattered fighting, and had ridden down an escaping Yorkshireman. Jeremy saw for a moment at his bridle the backward-turned, terror-distorted face and slashed at it fiercely with his whip. The man fell and lay still; and Jabez with a convulsive leap passed over the body. Out of the corner of his eyes Jeremy half saw, only half realizing it, that one of the Speaker’s men was jabbing with his bayonet at a wriggling mass on the ground beside him. Then they were through that skirmish, and for a couple of hundred yards in front of them the field was empty. But the gentle slope beyond was covered with small figures, running, dodging, stopping and striking with the furious and aimless vitality of the ants in a disturbed nest. Jeremy and Jabez had hastened into the midst of them before Jeremy was overtaken by a belated coolness of the reason. When the sobering moment came, he wished he had had the sense to keep out of this confused and murderous struggle, and at the same time he remembered that his only weapon was a pistol still strapped in its clumsy holster. He reached for it and began to fumble with the straps; but while he fumbled a desperate Yorkshireman, turning like a rat, pushed a rifle into his face and pulled the trigger. It was not loaded. Jeremy, trying to understand that he was still alive, saw in an arrested instant like an eternity the man’s jaw drop and his eyes grow rounder and rounder, till suddenly the staring face vanished altogether. Jabez, shaken to his knees by the man’s onset, had grasped an abandoned pike and had stabbed upward.

Jeremy reined in and quieted the almost frantic horse. A cold sweat broke out on his face, and he felt a little sick. He wiped his forehead with his sleeve and looked faintly from the dead Yorkshireman to Jabez, who stood with the bloody pike in his hand, an expression of complacent excitement wrinkling the skin round his eyes. The fighting had already passed beyond them; and Jeremy without moving let it roll away noisily over the crest of the hill. He made no sign even when Jabez shouldered his weapon with a determined air and began to trudge off defiantly in its wake. But when the queer lolloping figure had already begun to grow smaller, Jeremy put his hands to his mouth and shouted:

“Jabez! Jabez! Come back!” Jabez turned, shook his head, waved the pike with warlike ferocity, and shouted something in reply that came faintly, indistinguishably against the breeze. Then he resumed his march, leaving his commanding officer alone.

It was over half-an-hour later that Jeremy found the Speaker. By that time the fighting was all over, and the fields, hardly changed in appearance by being dotted with a number of corpses, so soon to be resolved into the same substance as their own, were quiet again. In the course of his search, Jeremy encountered much that he would rather not have seen. He saw too many men lying face downwards with wounds in their backs, too many with tied hands and cut throats. He realized that a battlefield can too literally resemble a slaughter-house; and these evidences of the ferocity of an unwarlike race appalled him. And he even found one of the mercenary officers, of the sort that he had observed earlier in the day and had disliked, in the act of dispatching a prisoner, preparatory to going through his pockets. He advanced angrily on the man, who did not know him and turned with a curse from his just accomplished work to suggest that Jeremy’s throat would prove equally vulnerable. Held off by Jeremy’s pistol, he strolled away with insolent unconcern. Jeremy continued his way and at last discovered the Speaker, a couple of miles beyond the line on which the battle had been decided. As he came up, he could see that the old man’s dress was disheveled, and that his horse was lathered and weary, presumably from taking part in the pursuit.

By this time he was faint and exhausted, and he did not announce himself in the confident manner that might have been permitted him. He rode up slowly to the crossroads, where the Speaker and Thomas Wells were standing under a sign-post, and dismounted. They were deep in a conversation and at first did not see him. The Speaker’s thick voice came in rapid jerky bursts. His reins were lying on the horse’s neck, and he gesticulated violently with his hands. The Canadian, whose eyes seemed to Jeremy to burn with a fiercer red than ever, spoke more slowly, but there was a kind of intense richness and gusto in his tone. Jeremy felt too inert to make any sound to attract their attention; but as he came nearer Thomas Wells touched the Speaker’s arm and pronounced deeply:

“There’s your hero!”

The Speaker dismounted and, running without consideration of dignity to Jeremy, clasped the astonished young man in his arms.

“You have done it! You have done it!” he cried again and again. “There is nothing left of them!” Then, when his transports had abated a little, he went on more calmly. “We have smashed them to pieces. The rebel army has ceased to exist, and the Chairman has been killed.”

“Killed?” cried Jeremy, in surprise.

“Yes, killed,” the Canadian interjected, still in the saddle and leaning down a little to them. “There’s no doubt that he’s dead. I killed him myself.”

“But was that wise —” Jeremy began. “Wouldn’t it have been better to keep him? It would have given us a hold over his people.”

“That’s what he said,” the Canadian answered drily. “He seemed quite anxious about it. But I always go on the principle that you can’t be sure what any man is going to do unless he’s dead. Then you know where he is.”

“Yes, he’s dead, he’s dead,” the Speaker broke in, in a rising voice. “The scoundrel has got what he asked for. He’ll never lift his hand against me or my people again!” Jeremy, dismayed and sickened, saw in the old man’s posture something of the inspiration, of the inhuman rage, of a Hebrew prophet. He dared not look at Thomas Wells, from whose grinning mouth, he fancied, as from that of a successful ferret, drops of blood must still be trickling.

“But it was you that gave him into our hands, Jeremy,” the Speaker resumed, in a softer and caressing voice. “You did for him — you killed him. All the thanks is yours, and I shall not be ungrateful!”

The Canadian laughed, low and ironical. Jeremy’s stomach for a moment revolted and a thick mist of horror swam before his eyes.

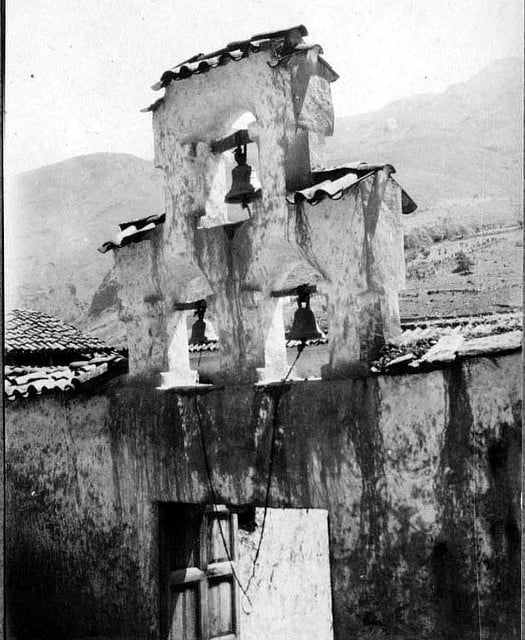

“Listen! Listen to the bells!”

Jeremy roused himself, cocked his head and listened. He was riding slowly beside the Speaker down the long undulations of the Great North Road that led them back to London. Sure enough, far and faint but insistent, that sweet metallic music reached his ears, a phantom of sound that stood for a reality. London was already rejoicing over its deliverance. A thin haze covered the city; and out of it there rose continuously the ringing of the bells.

“I sent messengers in front of us,” the Speaker went on, with great content. “They will be ready to greet us — to greet you, I ought to say. This has been your battle.”

Jeremy bestirred himself again. An urgent honesty drove him to do what he could to make the truth plain. It was pleasant, and yet intolerable, that he should be saddled with a victory that he had won only because he had been the instrument of fortune. He reasoned earnestly with the old man. He pointed out to him what a piece of luck it had been that the Yorkshiremen were fools enough to leave their transport exposed. He insisted that it was a mere chance that the destruction of their ammunition had thrown them into so disastrous a panic. When at last he was silent, the Speaker resumed, unmoved:

“It was your battle, Jeremy Tuft. You settled them. I was right to rely on you.”

The Canadian, who was riding on the Speaker’s left hand and had not yet uttered a word, breathed again upon the air a shadow of ironical laughter, which Jeremy felt rather than heard, and which the old man disregarded.

“They will come out to meet us,” the Speaker murmured in a rapturous dream, “and you shall be toasted at our banquet. Ah, this is a great day, a wonderful day! England is restored. Happiness and greatness lie before us. I shall be remembered in history with the good Queen Victoria.” He turned a little in the saddle and looked keenly at Jeremy. “Do you not ask what lies before you?”

Jeremy, staring straight in front of him, knew that he was reddening and swore inwardly. He wanted to be left alone.

“I’m glad you’re pleased,” he muttered, awkwardly and absurdly; and he began to calculate how far they were now from Whitehall and how much longer the journey would take. He supposed that he would be overwhelmed with undeserved congratulations at the end of it; but he reckoned that under them it would be his part to be dumb and that no disconcerting questions would be asked of him. The Speaker was too happy to do more than smile at the young man’s moodiness. As they rode along he continued his murmurings, which rose now and then into loud-voiced rhapsody.

In the daylight Jeremy vaguely recognized the country through which he had passed, in darkness, on the previous night, for the first time for many generations. At the Archway Tavern, which looked even ruder and more squalid under the sun than under the moon, the innkeeper and his family threw flowers at them and shouted uncouth blessings. But as they passed through Holloway and Islington, deserted and ruined districts, only a few squatters appeared to watch the conquerors march by. These hardly human beings displayed no emotion save a faint curiosity. They stood by the roadside, singly or in little groups, here and there, and gazed on the triumphant cavalcade with enigmatic faces. They reminded Jeremy of horses which he had seen gathering at a gate by the railway-line to watch a train go past. Their thoughts, their expectations, their hopes and fears, were as much hidden from him as were the minds of animals. And, as he looked at them, he experienced a singular pang. What to these creatures was all human history? What did it matter to them whence he had come, what he had done, what his future fortunes might be? Their sort, oppressed and tortured, had risen and had smashed in pieces the vast machine that tortured them, destroying by that act all that made life gracious and pleasant, and accomplished for their masters. It mattered so little to them what their own ancestors had done: it could not much matter what had been or would be the deeds of Jeremy Tuft, what edifice the old Jew would erect on the foundation laid by the victory. They gaped a little as they stared. Their attention was fleeting: they turned away and spoke and laughed among themselves. Jeremy felt in a piercing instant the nullity of human striving; and his blood was chilled.

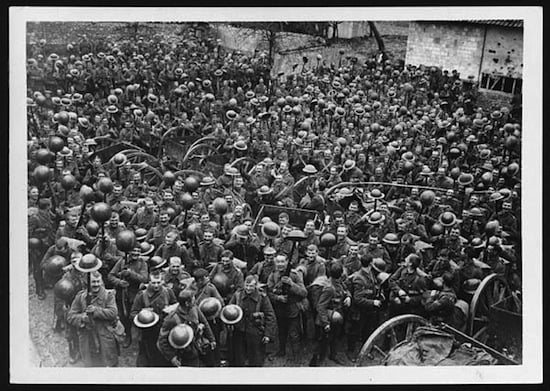

When they reached the crossroads at the Angel, they went through a more elaborate repetition of the ceremony at the Archway Tavern. A deputation of good villagers brought out hastily twined wreaths to them, waved cloths in the air and shouted loyally; and the Speaker, bowing his thanks and his gratification, urgently commanded Jeremy to do the same. So it went all the way, save that the demonstrations grew increasingly elaborate, and as they approached the city became continuous. The people were throwing down flowers from their windows and hanging out flags. At the doors of the larger houses crowds were assembling to receive free distributions of beer; and down some of the turnings off the main street Jeremy could see rings of men and women beginning already to dance and romp in the abandon of an unexpected holiday.

In Piccadilly the crowd had grown impenetrable; and by the spot where the Tube Station had stood they were brought to a halt and remained for some minutes. Loud and incessant cheering mingled with the noise of the bells. Daring young girls ran out from the crowd to hang the victors with flowers; and Jeremy saw with concern the profusion of blossoms covering first his horse’s head and at last mounting up round his own. The mechanical bowing and smiling, which the Speaker had enjoined on him began to tell on his nerves. He was conscious of bright eyes persistently seeking his, as the lingering hands fastened garlands wherever there was room for them, on his saddle or on his coat. He turned his head uncomfortably this way and that, shifted in the saddle, sought shamefacedly the eyes of the Canadian for some sort of sympathy. When he saw that Thomas Wells had had few wreaths bestowed on him and was grinning with more than his usual malice, he looked away again hastily.

The noise and movement around him continually increased; and it seemed that every minute some new bell found its voice and the crowd grew larger. Jeremy felt crushed and stunned, felt that he was sinking under the weight of the people’s enthusiasm. He felt so small and so oppressed that it seemed impossible that most of this could be meant for him. And yet vaguely, dully, he could see the Speaker at his side, pointing at him and apparently shouting something. He could not make out what it was; but he knew that every time the Speaker paused the continuous yelling of the crowd rose to a frantic crescendo, in which the whole world seemed to sway dizzily around him.

Suddenly, when he thought that he could bear no more, there was a wavelike motion in the press before them; and it broke open, leaving a passage through it. A carriage advanced slowly and stopped; and out of it came the Lady Burney, followed by the Lady Eva, each of them carrying in each hand a small wreath of green leaves. Jeremy, petrified, watched them walking through the narrow clear space. The Lady Burney moved very slowly with corpulent dignity and acknowledged the cheering as she came, while the Lady Eva seemed nervous, and looked persistently at the ground. When they reached the little group of motionless horsemen, the Lady Burney would have handed a wreath to the Speaker, but he signed her away, crying in a loud voice:

“Both to Jeremy Tuft! Both to Jeremy Tuft!”

The crowd redoubled its vociferations, while Jeremy, feeling himself at the lowest point of misfortune, leant over to the Lady Burney. She deposited both of her wreaths somewhere, anywhere, on the saddle before him and then, raising her arms, firmly embraced him and planted a kiss on his cheek, just underneath the left eye. He nearly yelled aloud in his astonishment; but before he could do or say anything, she had rolled away and the Lady Eva was standing in her place.

It seemed to Jeremy at this moment that the shouting abruptly grew less, and that as the noise faded the surroundings faded too, and became misty and unreal. There was nothing left vivid and substantial in the world but himself, numb, dazed, unhappy, and the tall girl beside him, her face bravely raised to his, though her cheeks were burning. She, too, seemed, by the convulsive movement of her hands, to be about to put her wreaths on any spot that would hold them, but, with an effort that made her body quiver, she controlled herself and placed one on his head, from which the hat long since had gone, and fastened the other on his breast. She did this with interminable deliberation, while the people maintained their astonishing quietude. Then, after a pause, she put her arms round his neck and placed her lips on his cheek. At this signal the crowd’s restrained joy broke out tumultuously. Jeremy closed his eyes and swayed over towards the girl, then caught at his horse’s mane to save himself as she slipped away.

When they began to move again, he had lost all control of himself. He shivered like a man in a high fever, his teeth were chattering, and he was sobbing ungovernably. He had afterwards a confused memory of how they proceeded slowly down the Haymarket into Whitehall, and how a dozen helpers at once sought to lift him from his horse outside the door of the Treasury.

Jeremy’s next distinct impression was that of sitting in a small room while the Speaker poured down his throat a glass of neat smoke-flavored whisky. It revived him, and he straightened himself and stood up, but he found that his back ached and that his legs were unsteady. The Speaker forced him down again and bent over him tenderly, muttering caressing and soothing words at the back of his throat.

“You will feel better presently,” he said at last; and he went out softly, looking back and smiling as he went. When he was alone, Jeremy rose again and walked towards the door, but was checked at once by a great fatigue and weakness. He looked round the room, and, seeing a couch, threw himself at full length upon it.

“I wish I could go to sleep,” he murmured to himself. But his brain, though it was exhausted, was so clear and active that he gave up all hope of it. When, a minute later, sleep came to him, it would have astonished him if he could have noticed it coming.

He woke to wonder how long he had been unconscious. It had been about noon when they had arrived at the Treasury; but now the tall trees outside the window hid the sky and prevented him guessing by the sun what hour it was. He turned over on to his back and stared up lazily at the ceiling. The confusion which had at first overwhelmed his mind, and the unnatural clarity which had followed it, were both gone, and he felt that he was normal again, not even very much tired. The indolence and calm of the spirit which he now experienced were delicious: they were like the physical sensations which succeed violent exercise.

He looked down again with a start, as he heard the door quietly opened; and he saw the Lady Eva standing there. She had a mysterious smile on her lips, and her whole attitude suggested that she was bracing herself to meet something which frightened but did not displease her. Jeremy rose abruptly, his heart beating, and tried to speak; but he could not get out a single word.

“My father sent me to ask if you were better,” said the Lady Eva in a low voice. As he did not answer she closed the door behind her and advanced into the room. “Are you better?” she repeated, a little more firmly. Jeremy took a step towards her and hesitated. The situation seemed plain, and yet, at the last moment of decision, his will was paralyzed by a fear that he might be absurdly deceiving himself.

“I am much better now,” he answered, with an effort. “I only feel a little tired.”

“There is a banquet at five o’clock. I hope you will be able to attend it.”

Jeremy shivered slightly and his wits began to return to him. “Will it be like — like this morning?” he enquired with a faint smile.

She smiled a little in reply. “Don’t you want us to be grateful to you?” she said. “You know what you have saved us from — all of us. How can we ever reward you?”

“That’s my chance,” Jeremy’s mind insisted again and again. “That’s my chance… that’s my chance… I ought to speak now.” But the short interval of her silence slipped away, and she went on gently:

“You must expect to be congratulated and toasted. Will you be strong enough to bear it? My father will be disappointed if you are not.”

It was at that moment, quite irrelevantly and by a process he did not understand, that Jeremy took the Lady Eva in his arms. Afterwards he had no consciousness, no recollection, of the instant in which their lips had met. There had simply been an insurgence of his passion and of his loneliness, ending in an action that blinded him. The next thing he remembered was folding her bowed head into his shoulder, stroking her smooth hair with a trembling hand, and muttering hoarsely and helplessly, “Dearest… dear one…”

Then they were sitting side by side on the couch and their positions were reversed. His head lay on her shoulder, while her fingers moved gently up and down his cheek. He stayed thus for some minutes without speaking or moving. He had been in love before and had not escaped the mood in which young men picture the surrender of the beloved. He had even more than once, after a long or a short wooing, held a girl in his arms and kissed her. But he had never yet seen this sudden and astonishing transformation of a stranger, mysterious and incalculable, whose faults and peculiarities were as obvious as her beauty was enchanting, into a creature who could thus silently and familiarly comfort him. The moment before she had been some one else, the Lady Eva, a person as to whose opinion of himself he was uncertain and curious, that most baffling and impenetrable of all enigmas, another human being, divided from him by every barrier that looks or speech can put in the way of understanding. And now she was at once a lover, a part of himself, a spirit known by his without any need of words. He adjusted himself slowly to the miracle.

Presently he raised his head and searched her eyes keenly. She bore his gaze without flinching; and something again drew their mouths together. Then Jeremy said.

“I must speak to your father at once. Do you suppose he will feel that I have presumed on his gratitude to me?”

“I know he will not,” she answered. “I am sure he meant to give me to you. Do you think that otherwise…” She stopped, and there was a long pause. “But I wanted you… first…” Again she could not go on, but began to sob a little, quietly. Jeremy, helpless and inexperienced, could think of nothing better to do than to gather her into his arms and kiss her hair. His sudden comprehension of her seemed to have vanished with as little warning as it came. She was again a mysterious creature; but now the mystery was a new one. He was like a man who, after the triumph of accomplishing a steep ascent, finds that he has reached no more than the first slope of the mountain.

When her face was hidden she continued with more confidence, but in a low and broken voice. “I wanted you to tell me that you… wanted me, before my father gave me to you. I thought… perhaps you did… I hoped…” She freed herself from his arms and sat up, looking at him with proud eyes, though her face was blazing. “It is better than being given to you only as a reward for winning a battle,” she finished deliberately.

Jeremy experienced the most inexplicable feeling of the young lover — admiration for the beloved. He wished to hold her away from him, to contemplate the lovely face, the gallant eyes, to tell her how wonderful she was, and how he could thank Heaven for her even if he might never touch her hand again. And on the heels of this came a great rush of unbearable longing, with the realization that human tongue was not able to express, or human nerves to endure, his love for her. He turned dizzy and faint, his sight went black, and he stretched out his arms vaguely and helplessly. When she gave herself into them, he clasped her fiercely as though by force he could make her part of himself, and she bore his clumsy violence gladly.

“This hurts me,” he said in the puzzled voice of a child, when he had let her go again. She gave him with wet eyes a sufficient answer. Then he went on with the same simplicity, “I have been so lonely here —I didn’t know how lonely. Are we going to be happy now? I am afraid… of what may happen…” She kissed him once and rose.

“I must go now,” she said steadily. “Oh, we shall be happy — this dread means nothing, it is only because we are so happy.” He started and looked at her, made uneasy by her echo of his thoughts. “Good-by, my dear,” she said. She left the room quietly without his raising a hand to keep her back.

When she had gone his feelings were too violent to find vent in any movement. He sat quite still for some minutes until his brain was calmer and he could at last stand up and walk about the room. It was thus that the Speaker found him; and Jeremy stopped guiltily and stood waiting. The old man was evidently still in good humor. He stroked his chin and regarded Jeremy with beaming eyes.

“I take it you are feeling better,” he pronounced drily, after a moment’s silence.

“I am quite well,” Jeremy answered hurriedly, “very well. I must tell you at once, sir —”

The Speaker stopped him with a gesture. “I know. I passed my daughter in the corridor leading to her room. You want to tell me that you have taken my gift before I could make it. Nevertheless, I shall have the great joy of putting her hand in yours at the banquet to-night.”

“I can’t thank you…” Jeremy mumbled.

The Speaker made a benevolent movement of his hand. “What you and she have done,” he went on, “is much against our customs, but we are not ordinary people, you and I and she. You will be happy together, and it will make me happy to see you so. And I think you are young enough to get from her the help that I should have had, if there had not been so many years between us. She has something of me in her that you will be able to use. You will need to use it, for you will have a great deal to do, both now and afterwards, when I am gone and you are the Speaker.”

Jeremy inclined his head in silence.

“The banquet is in half an hour from now,” the Speaker said, turning towards the door. “If you are well enough to attend it, you must go and dress at once.”

NEXT WEEK: “At the end the servants cleared the table, and, with the costly Irish cigars, great decanters were brought in. These contained a kind of degenerate port which, for ceremonial reasons, was usually produced on the greatest occasions. But it was very nasty; and most persons confined themselves to a single glass of it, which they took because, for some inscrutable reason, it had been the custom of their ancestors.”

RADIUM AGE SCIENCE FICTION: “Radium Age” is HILOBROW’s name for the 1904–33 era, which saw the discovery of radioactivity, the revelation that matter itself is constantly in movement — a fitting metaphor for the first decades of the 20th century, during which old scientific, religious, political, and social certainties were shattered. This era also saw the publication of genre-shattering writing by Edgar Rice Burroughs, Sax Rohmer, E.E. “Doc” Smith, Jack London, Arthur Conan Doyle, Aldous Huxley, Olaf Stapledon, Karel Čapek, H.P. Lovecraft, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Yevgeny Zamyatin, Philip Gordon Wylie, and other pioneers of post-Verne/Wells, pre-Golden Age “science fiction.” More info here.

HILOBOOKS: The mission of HiLoBooks is to serialize novels on HiLobrow; and also, as of 2012, operating as an imprint of Richard Nash’s Cursor, to reissue Radium Age science fiction in beautiful new print editions. So far, we have published Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague, Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”), Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt, H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook, Edward Shanks’s The People of the Ruins, William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land, and J.D. Beresford’s Goslings. Forthcoming: E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man, Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage, and Muriel Jaeger’s The Man with Six Senses. For more information, visit the HiLoBooks homepage.

READ: Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague, serialized between January and April 2012; Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”), serialized between March and June 2012; Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt, serialized between April and July 2012; and H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook, serialized between March and August 2012.

ORIGINAL FICTION: HILOBROW has serialized three novels: James Parker’s The Ballad of Cocky The Fox (“a proof-of-concept that serialization can work on the Internet” — The Atlantic) and Karinne Keithley Syers’s Linda Linda Linda. We also publish original stories and comics.