Pop Arcana (7)

By:

July 25, 2012

RICK GRIFFIN, SUPERSTAR

PART TWO

[Here’s PART ONE]

In 1969, Rick Griffin left San Francisco, whose psychedelic underground he helped broadcast to the world with his remarkable posters and comix. Drawn to the more various and mellow surfer lifestyle of the southland, Griffin returned to SoCal with his girlfriend and settled in San Clemente to enjoy the waves, though the move may have been motivated as well by whatever spiritual struggles Griffin was going through at the time. In 1970, Griffin was filmed surfing at the remote and legendary Hollister Ranch for John Severson’s classic surf film Pacific Vibrations, which also features footage of Griffin and some pals tripping-out a hippie bus with spray-paint.

After creating his first major acrylic painting for the film’s poster, Griffin drove up and visited some friends in Mendocino, freaks who, in that freaky way peculiar to the era, had become Christian. On Griffin’s return trip, the story goes, his car broke down, and somehow he walked away from the experience with Jesus as his lord and savior. Soon he started attending a local Baptist church, married his girlfriend Ida, with whom he already had two kids, and dedicated his life and art to Christ.

This was not your granddad’s gospel, however. Griffin became a Christian during the heyday of the Jesus People, a distinctly countercultural expression of American Christianity that would come to mainstream prominence in 1972, when a host of major magazine articles and books brought a great deal of attention to the hirsute holy ones who so peculiarly combined — in a variety of ways — hippie values with rock solid biblical faith. For many of the Jesus People, the Lord became a kind of guerrilla guru, an intimate and revolutionary spiritual pal who offered, in the face of countercultural chaos, “One Way” to go. In a famous Wanted poster that first appeared in the UC Berkeley Christian street paper Right On!, Jesus is described as a “notorious leader of an underground liberation movement” with a group of disreputable followers and the “extremely dangerous” potential to set people — especially young people — free.

Though the Jesus People popped up independently across the West Coast, its beginnings are usually traced to the Bay Area, and especially to a Haight Street coffee shop called the Living Room set up by Ted Wise and some recent freak converts in 1967. A small commune in Novato called the House of Acts emerged from the spot, one of whose members — whose cherubic charisma was only matched by his remarkable name of Lonnie Frisbee — subsequently moved to Orange County. There he sparked the most important Jesus Freak cross-over revival when he started preaching with tremendous success to kids at Chuck Smith’s Calvary Chapel, which would, along with John Wimber’s splinter OC Vineyard movement, go on to significantly influence the language, look, and feel of modern American evangelism. Other developments in Jesus Freakery, such as Dave Berg’s cultish Children of God, would spin out in the other direction, towards apocalyptic isolationism, while a third wave, represented by Hollywood’s Arthur Blessitt (get it?), could be seen as repackaging the basics of Christian life into groovy day-glo kitsch of bumper-stickers, t-shirts, and, yes, cartoons.

The Jesus movement shared with many Protestant revivals the experience — or at least the belief in the experience — of direct and personal participation with the living reality of Jesus Christ. This transcendent encounter came before the ideological commitment to dogma; as such, it fit the countercultural predilection towards intense experience, even if the call itself subsequently demanded the rejection of many countercultural values. Many Jesus Freaks, like Frisbee, first glimpsed the One Way on LSD; even when drugs were set aside, forms of worship and communion retained the strong experiential character found in market competitors like the Hare Krishnas. In any case, whatever offshoot of whatever ministry Griffin came in contact with, it is clear that his conversion was a profoundly singular and personal experience. As such, it is outside our view. However, as was pointed out in part one of this essay, conversion is not a singular event, but the rapid precipitation of a long-brewing stew of psychic tensions, powerful intuitions, and sacred desires. As a profoundly psychedelic illustrator, Griffin was already a kind of assemblage artist of private and public symbols; as such, he was able to picture something of own “conversion stew” in his art.

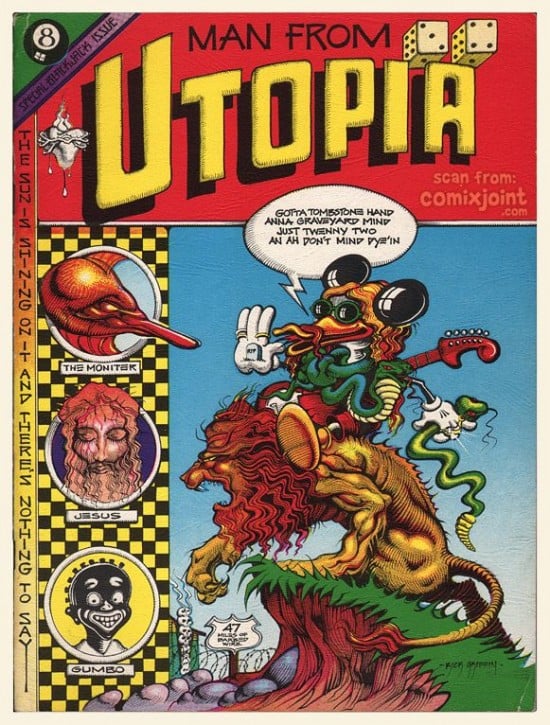

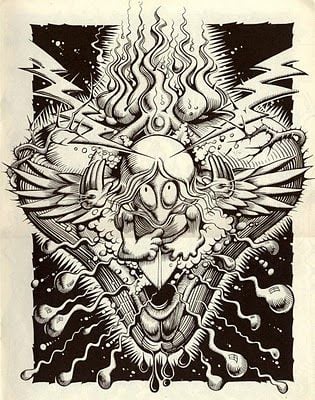

This is, in any case, how I think we should understand The Man from Utopia, a bizarre and remarkable 28-page publication Griffin released in 1970. Printed on high quality paper rather than the usual pulp, The Man from Utopia is more of a portfolio of thematically related black and white panels than a narrative. (Some say Griffin was tripping when he gave the panels to the printer and presented them out of order.) On the thick, card-stock cover, which parodies classic comics format, Jesus appears as one of the stars, along with a vaguely malevolent duck-billed creature with a Roman brush helmet identified as “The Moniter” (Griffin was never a great speller).

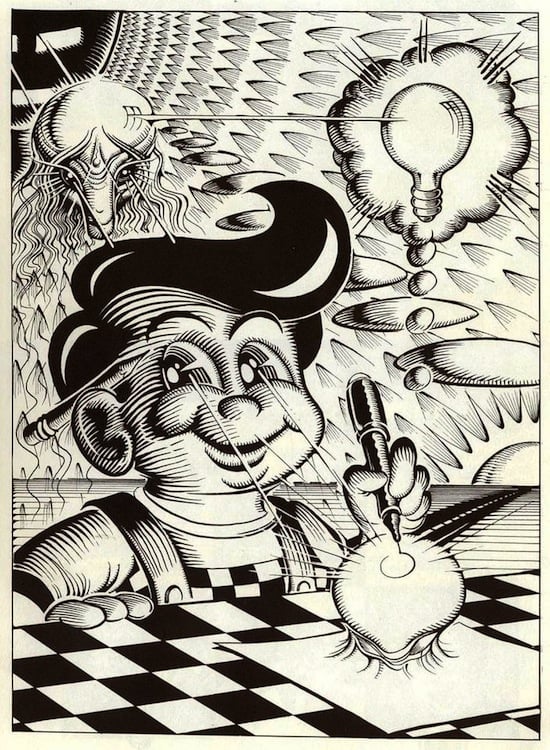

The Man from Utopia refuses summary as it refuses overall coherence, but its recurrent images and narrative fragments resonate with a remarkable intensity, its heavy, sometimes demonic imagery balancing the daffy bounce of mainstream cartooning, and creating a profound expression of psychedelic cognition. Indeed, one of its pages stands, for my money, as one of the most telling and perceptive works of self-reflexive psychedelic art we possess, a self-reflexive and metaphysical incarnation of a certain imaginal bardo I like to call the cartoon continuum.

This shamanic portrait of the mascot for the Bob’s Big Boy restaurant chain reminds us that, like his Zap mate Robert Williams, Griffin was a master of juxtapose, the essential countercultural art of combining sublimity with the banal, avant-garde experimentalism with pop crap, art and illustration. Both artists, but especially Williams, also display a much rarer talent for envisioning the specifically diagrammatic dimension of psychedelia — that is, the degree to which the images and concepts unfolding in the tripper’s mindstream can be understood as a kind of morphological flow-chart of transformation and replication that results in graphic “lattices of connection” that are themselves the result of something far more abstract, something we might think of as pattern as such. With Bob’s Big Boy, we have an echo of Griffin’s earlier Ain Soph page, as the abstract Hopi mask of the Absolute — mostly outside the panel — emanates a bizarre but more earthy god, with the almond eyes and cranial shape of an alien grey. In one reading of the diagram, this being then zaps the artist with an inspiration whose one-step-removed manifestation — the light bulb — is a mimetic morphological echo of the being’s own shape that is simultaneously symbolic “cartoonese” for a Eureka moment, which is exactly what Bob — the visionary artist who is also a commercial illustrator — seems to be having amidst this radiating Möbius strip of form and content.

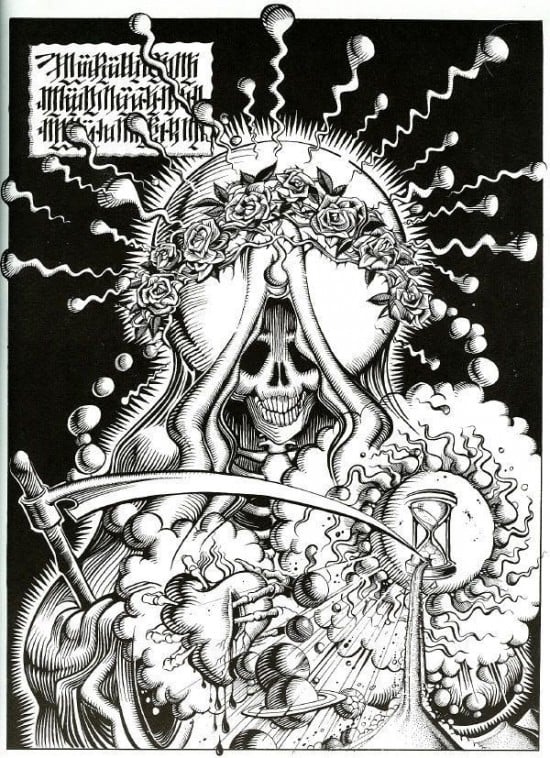

Notice as well that the copy of the shape that the artist is drawing is expanding into three dimensions. These shapes are alive. And indeed, the alien-lightbulb form transforms and recurs throughout the book, a process of morphological resonance and transmutation that Griffin raises to a daemonic and deeply psychedelic pitch — “cant quite putcher finger onit,” goes one caption, “some kinda warp.” Though only some of these images feature Jesus or Christian symbols, a sense of terrible spiritual enantiodromia runs throughout the book, as if the Zappish demon armies pictured within contain the seed of some sacred personality who might in turn keep the dark at bay, or as if sex conceals a sacred secret that remains nevertheless obscene. Everywhere is sex-and-deathery. One image modifies Stanley Mouse’s classic “skull and roses” Grateful Dead poster by adding a labial cloak and a penetrating cosmic scythe.

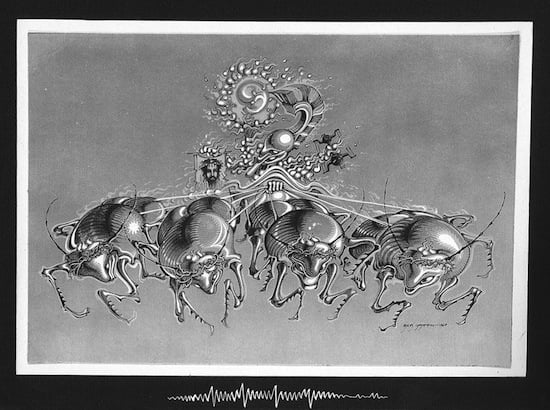

But it is the Jesus images that seem, through their very out-of-placeness, the most disturbing. In one panel, the Moniter — looking not unlike Marvin the Martian — is shown clutching a Veil of Veronica as he maneuvers a Roman chariot led by scarabs.

Elsewhere, the Moniter’s lightbulb head appears on the crucified Christ, also crowned by the antlers seen on the All Stars cover. These are personal images beyond our ken, perhaps unknown to Griffin himself, who, contemporary photographs show, had hung a similar pair of antlers on the wall of his studio, alongside a soft charcoal image of Jesus photographed and included in The Man from Utopia under the title “Our Darling.” Perhaps the most shocking Christian image is also, again paradoxically, the goofiest.

Holding out his hands punctured with eyeball stigmata, a Murphyish surfer with Aoxomoxoa egg-shaped eyes nose-rides towards us in a burst of foam that emerges from a juicy and explicitly vaginal sacred heart. (Recall the split beaver in the All-Stars cover.) Lest we jump to conclusions as to the profanity of such a conjunction, it should be recalled that the famous and influential eighteenth-century German Pietist Count Zinzendorf encouraged his followers to meditate on Christ’s side wound as a vulva, an organ of spiritual rebirth. And indeed, that is what Griffin has given us, and given himself as well: the ultimate carnal-cosmic Jesus Freak icon of being born again.

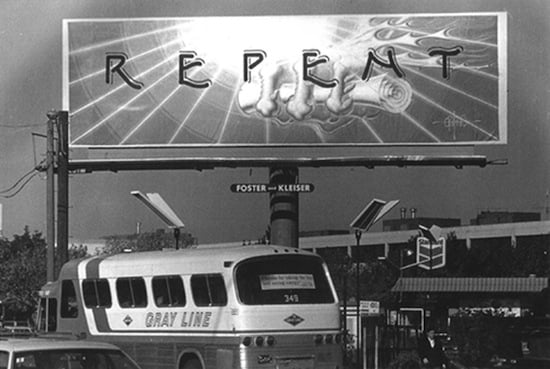

Though the intensity of The Man from Utopia would reappear in other pieces from the early 1970s (“Tales from the Tube,” “OMO Bob Rides South”), Griffin did shift the focus and ultimately the style of his work following his conversion. He began doing work with southland churches, creating tracts and illustrating the cover for a directory produced by his local Baptist Church, and even doing an evangelical billboard.

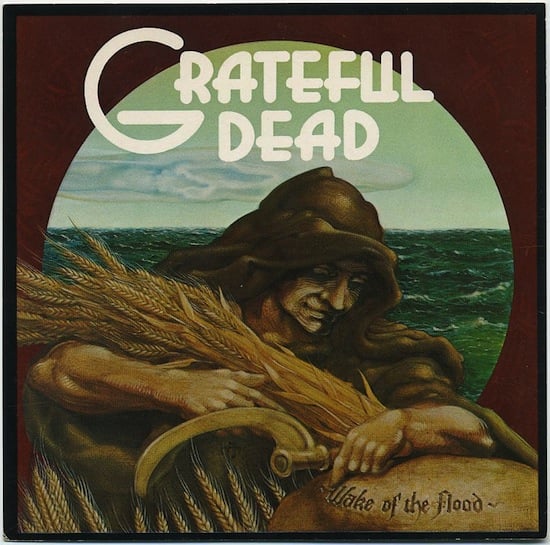

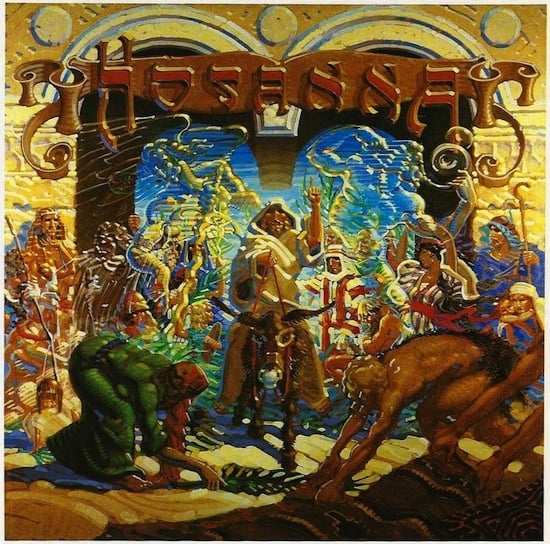

He consciously stepped away from some of his earlier concerns, reducing and even mocking his earlier reliance on esoteric symbolism. When he reprinted a famous psychedelic Murphy strip called “Mystic Eyes,” he replaced the explanation he had earlier furnished of one magic square with the phrase “Primitive Pre-Salvage Mumbo Jumbo!” At the same time, however, Griffin continued work for “secular” outfits like Surfer magazine, Zap, and the Grateful Dead. While part of the forces here were probably commercial, Griffin also had the freedom to evangelize in his own oblique way — and the youth culture at the time was not too hide-bound to accept it. And so he laced Christian images and prayers into recognizably Griffinesque scenarios, like claustrophobically illustrated Mexican adventure comics or surf tales starring his old character Murphy. Though some of his underground comix pals were unhappy with his new life — a few reportedly tried to “bring him back to the fold” by bursting into his home with a bottle of tequila, only to wind up drunk themselves — R. Crumb for one continued to support his work. Zap #7, from 1974, included a beautifully minimalist four pages from Griffin called “And God So Loved the World,” which appeared alongside the usual bestial S&M romps. Stylistically, Griffin started to turn away from psychedelic density towards more accessible designs influenced by classic children’s book illustrations and what Doug Harvey calls “orange crate art.” A marvelous expression of this was Griffin’s cover for the 1973 Dead album Wake of the Flood (Griffin would continue to provide images for the Dead throughout his life).

Though the biblical verse originally pegged to the image got squashed, the image shows familiar Griffin concerns, including the round portal shape, the sea, and the scythe. Indeed, the continuity between Griffin’s commercial and visionary imagination, as well as his secular and Christian work, can be seen by lining up the Dead piece with another album cover he did two years later for the California soft-rock Christian band Mustard Seed Faith.

Once again, the sea and the circular portal both suggest mortal transition, though here that passage is no longer somber but illuminated with the amazing splash of fairy-tale light we associate with Howard Pyle or Maxfield Parrish. It became a popular Christian image in the southland, and was subsequently appropriated for the 1977 album Point of No Return by the group Kansas, whose primary songwriter Kenny Livgren in turn converted to Christianity in 1979.

Mustard Seed Faith was on the Maranatha! Music label, which subsequently hired Griffin as art director, giving him and his family a badly-needed steady paycheck and a new home in Santa Ana. Maranatha! was also associated with Chuck Smith’s aforementioned Calvary Chapel, whose ministry, since Lonnie Frisbee had come and gone, had done the most successful job of wedding the earnest and emotional informality of Jesus Freakery to more institutional forms of American evangelism. Indeed, by the mid 1970s, the Jesus Movement was already dissolving into the mainline, where it would paradoxically both intensify the activist politics associated with issues like abortion and birth the more intimate and even magical experience of Jesus that the Stanford anthropologist Tanya Luhrmann has analyzed in her excellent recent book When God Talks Back. As far as popular culture goes, the 1970s was the era when American evangelism flip-flopped, moving from the judgmental separatism of the old, “rock’n’roll is the devil’s music” days to the slutty embrace of popular cultural forms and subcultures that define (and render indefinite) today’s exceptionally generic vernacular Christian culture. The Jesus Freaks were the hinge of this transition. Like the hippies, they staked their authenticity on cultural expressions (lifestyle, rock music, popular iconography) that would — paralleling the counterculture’s transformation into dominant commercial culture — become absorbed by more mainstream and conservative currents through the 1970s and early 1980s.

As part of that process, Chuck Smith asked Griffin to provide the illustrations for a paraphrased version of The Gospel of John, perhaps the most important book of the New Testament for American evangelicals. The Gospel of John, which was reissued a few years ago in a handsome hardbound volume with extra images not featured in the original 8 ½ by 11 slick magazine format from the 1980s, was Griffin’s last great work. The images alternate between acrylics and black-and-white line drawings, which includes brilliant and sometimes playful cartoons for the chapter numbers — chapter nine, in which Jesus heals a blind man, is accompanied by two flying eyeballs. Though he brought a certain reverence to the task of illustrating scripture, Griffin did not hesitate to continue the canny reflection on popular culture and commercial art-forms that had marked his entire career.

One illustration shows Bob Dylan — recently in the news for his own Christian conversion (brought about in part through the Calvary-inspired Vineyard Movement)— stepping though a portal of death; another image of Christ entering Jerusalem includes, along with images of Griffin (holding the staff) and his wife, a skateboarder wearing a Lynyrd Skynyrd t-shirt.

Though humorous, these images also expressed what Robert Ellwood described as the evangelist’s desire “to collapse into nothing all time between himself and the New Testament.” Stylistically, Griffin continued to reflect on the illustrations of N.C. Wyeth and Dean Cornwell, though with his acrylics he often preferred to replace those crisp classic lines with a more impressionistic air-brushed gestures. These strokes lent great but informal power to two of the most powerful images in the book, both of which feature water.

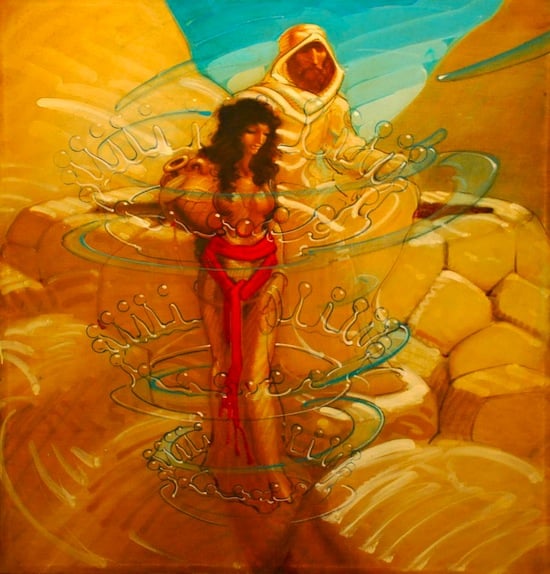

For his illustration of the encounter with the Samaritan woman at the well — one of the most beautiful stories in the gospels — Griffin presents a refreshingly erotically charged encounter and overlays it with a visionary rendering of three round splashing “crowns” representing the everlasting water that Christ offers the outsider woman. Looking close, we realize these are still the biomorphic love-spurts of yore.

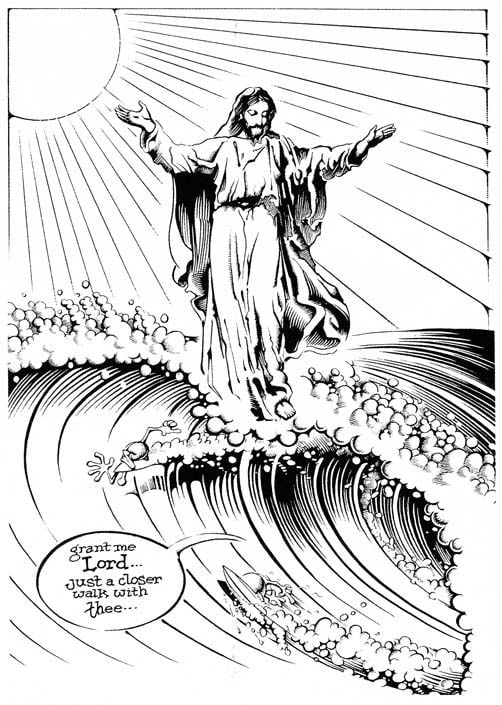

The other marvelous water image here is a green, moonlit scene of the boat-bound apostles cowering before Jesus as he walks towards them on the surface of a churning sea. Once again, for Griffin the prophetic is the personal. Though there is no board here, those with ears to hear can pick up the California Christian koan that Thomas Pynchon asks in Inherent Vice: “What was ‘walking on water’ if it wasn’t Bible talk for surfing?” Indeed, ghosting the image from the Gospel of John is an earlier Griffin drawing from the mid-1970s, one of those rare culture jams that are at once so audacious and economical that they both harmonize the juxtaposition and revel in its absurdity.

This marvel of spunky naïveté is more than documentary evidence for the cult of born-again surfers that, as Pynchon recognized, was and to some degree is a vital strand of southland beach culture. It also reminds us that for true soul surfers, the waves that mark the passage between our dust-to-dust world and the great sea are a face of creation. For Rick Griffin, this face belonged to Jesus, at least much of the time. In the late 1980s, Griffin seemed to “backslide” from the faith for a spell, but surfing remained his core communion.

After Griffin was killed on his Harley in 1991, his ashes were taken up to Mysto’s, a favorite surf spot near Fort Ross now known as El Griffo’s.

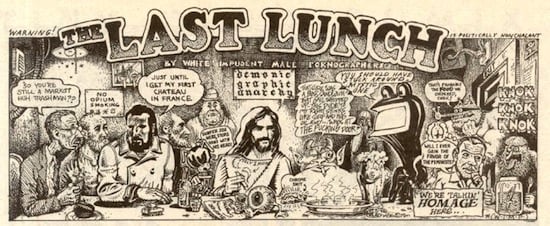

For the cover of the Zap that followed the artist’s demise, Victor Moscoso crafted a sunset surfer image featuring classic Griffiana — a flying eyeball, a stigmata hand, globular spume. But the greater homage came within, greater for being more crusty.

Here all Griffin’s old underground pals gang up together to offer a visual send-off to the “mystic one,” a religious parody that is made, by Griffin’s ghostly presence as a comix Christ, both more and less than a parody. One of the greatest strengths of Griffin was that, for all the intensity of his turn to Jesus, he never turned his back on his own artistic, cultural, and social heritage as a full-bore freak. Griffin may have leapt through the glowing portal, but he never really left the fold.

***

Pop Arcana is a limited-run series of columns written for HiLobrow by Erik Davis.