De Condimentis (14): Dress My Salad

By:

July 22, 2012

This is the fourteenth installment in Tom Nealon’s acclaimed and apophenic food history series De Condimentis.

Lettuce grew wild, in one form or another, over most of temperate Europe and Asia. It was cultivated by the Babylonians (it grew in the Babylon garden of King Merodach-Baladan), the Assyrians, and later the Greeks and Chinese. In Italy, they only had white lettuce, what the Greeks called “poppy lettuce” because of its white juice thought to be a soporific, and which the Italians called lactuca after its milky juice. But this isn’t the story of lettuce.

About fifteen minutes after humanity discovered salad, salad dressing was invented to combat the insipid bitterness of greens. For the next nearly five millennia, dressing remained footloose and fancy-free. As far as we know, for most of that time, nobody ever told anybody else how to dress their salad and if they did, it was in private; to do so, would have been akin to teaching your grandmother to suck eggs — and I think we all know how that turns out. The era of free-range salad dressing began to end during the early 19th century, however — the very period that Foucault identifies as the one during which the newly emergent bourgeoisie figured out how to relocate coercion within liberty. Coincidence? By no means.

The word salad comes from the Latin for salt as the Romans tended to use salty dressings, or just salt, on their salads. In fact, they would even use the salty fermented fish sauce liquamen as an ingredient in the most famous early salad dressing mortaria. Mortaria (literally something made in a mortar) was a common topping for salads and bread, and was so esteemed that its preparation was immortalized by Virgil. No doubt there were myriad variations of the recipe, but the ancient Roman cookbook often referred to as Apicius has just one version (Book one, recipe 35), as follows:

Fresh mint, rue, coriander, fennel

lovage, pepper, honey, liquamen, vinegar

Virgil included cheese (probably a salty cheese like feta) and salt, and left out the liquamen. In both cases the dressing that is being described is a condiment that has evolved into something more complicated — a sort of debauched dressing, which is fully in character with the late Roman Empire. Salad dressings have a tendency to increase in complexity — in fact, the only time you reliably see them written down is after they have increased in complexity enough to be worth the bother of doing so. However, for most of history, salad dressing was understood to be oil and vinegar with flavorings, a combination that when mixed in the right ratio and agitated will form a temporary emulsion. One that generally lasts long enough to enjoy your salad.

Apicius also includes simpler salad recipes, including dressing endive with liquamen (to remedy the bitterness) or with honey and vinegar, pickling lettuce leaves (also described by Columella), and dressing rustic greens with liquamen, oil and onion. It would take 1500 years and an Italian-American restaurateur named Caesar Cardini for fermented fish to fully regain its popularity as an element in salad dressing.

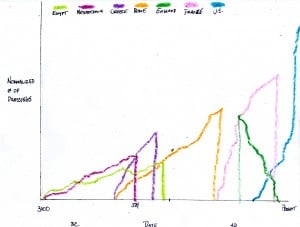

There is no doubt that salad dressing goes back much further than Apicius, but as is often the case, the Hebrews, Sumerians, Assyrians, Babylonians and Egyptians have left us little to go on. Which isn’t surprising — even into the 18th century in Europe, you rarely see recipes for something as simple and malleable as salad dressing. It is relatively easy to make intelligent guesses at salad dressing profusion, though, using non-cookery texts (trade and tax records, diaries, etc.). In fact, due in part to the relationship of oil and vinegar supplies to success in trade, commerce and agriculture, you can actually chart the rise and fall of civilizations based on their salad dressing options — note the tipping point where too many dressing choices signal the decadent phase on Empire.

Why was Macedonia unable to cope with the addition of Indian ingredients and dressings? Why is Britain the only Empire whose progression is reversed? Is chutney really responsible for the collapse of two empires? These are the questions that plague historians — I simply present the facts.

So for over 1000 years, salad dressing remained behind closed doors; everyone knew how to dress a salad, but no one was blabbing about it. If you liked garlic, long pepper and coriander with your oil and vinegar, no one was going to think any less of you, or worse, try to put a name to it. Salad dressing, like any proper condiment, had gone feral — it was a part of the human condition, just like its namesake salt. Which isn’t to say that it wasn’t leading an exciting, varied life, it was just doing so far from the codifiers, rule-makers and cooks. Whether a peasant wondering how to dress the jack-by-the-hedge he found down the hill, or a baronet searching after the perfect complement to the hyssop that his personal physician prescribed to ease melancholy, no one was looming about telling anyone how to do it, what to call it, or what it meant.

The famous, but often misunderstood, dish salmagundi is a fine example. Originally a “recipe” bouncing around 17th century England “composed of chopped meat, anchovies, eggs, onions, oil and condiments” (OED) salmagundi came to include cold turkey, chicken, and in Hannah Glasse’s important 1747 cookbook, “such things as you have according to your fancy”. It survived overseas in Jamaica as Solomon Gundy, a smoked fish paté — and as Solomon Grundy, a nursery rhyme and evil cartoon zombie.

Two unpublished Italian manuscripts (1572 and 1614) devoted to salads speak to the growing interest and importance of the consumption of leafy greens, but next to nothing (Scappi had a few words in his vital 1570 Opera) was set in type. But slowly, the renaissance interest in health and a rediscovery of the classical view of salads briefly brought salads and their dressing back into history.

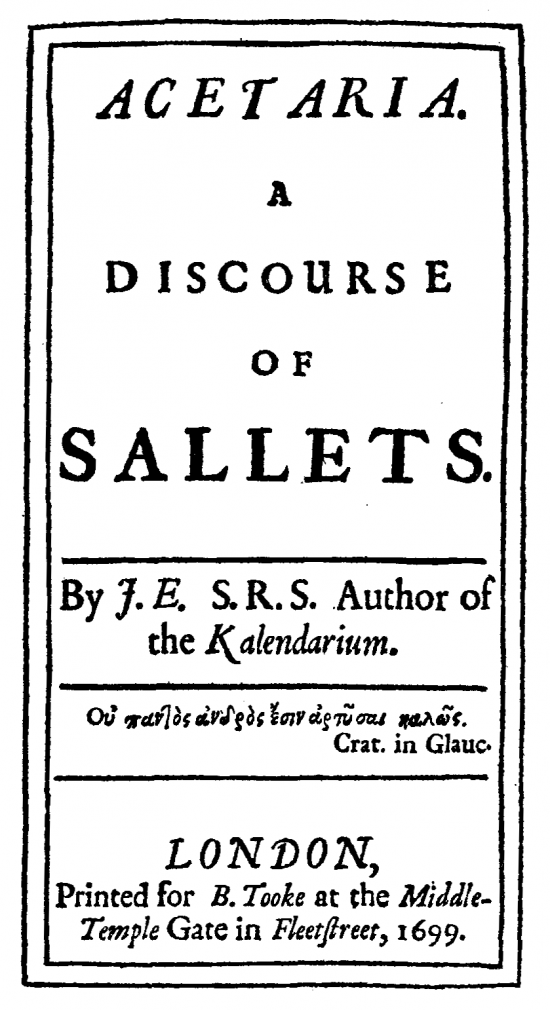

In 1699, the dynamic but hitherto secret life of salad found their Boswell. John Evelyn, today most famous for his diaries which provide the contrapuntal rural view to the London-centric mewlings of Samuel Pepys, but also the author of important treatises on trees, gardening, air pollution, and cider, wrote the first book devoted to salad, Acetaria: A Discourse of Sallets.

Inspired by his belief in a vegetable-based, or “Pythagorean” diet (shared by fellow enlightenment thinkers Voltaire and Rousseau), and with some inspiration from the great 16th and 17th century herbals, Evelyn defined and classified the ingredients of salad, their nature, affect on the humors (cf. Galen and the classical authors), and how they are dressed; a sort of natural history of salads cum herbal, more than a strictly culinary book. But because Evelyn’s book was more a collection of found recipes than an authoritative cookbook, more a description of what was out there than a prescription for making salad, it avoided being didactic. Perhaps it was this lack of didacticism, of authority, or perhaps it was because Acetaria ended up being appended to his Kalendarium Hortense, but salads went straight back underground.

In fact, salads made it all through the Renaissance and Enlightenment without being noticed much at all. Beyond a few careless mentions, the deluge of cookbooks in France, Italy, and England brought on by advances in cuisine and the ubiquity of the printing press, continued their silence on all things salad. As a food historian, I lament this fact. However, as a defender of individual liberty in matters great and small, I applaud our ancestors for their reticence.

During the early 19th century, salad and salad dressing began to emerge from their folkways, free-range underground into the crypto-authoritarian light of day. No less an authority on modern living than the Gentlemen’s Magazine had this to say in 1837:

Not one man in a hundred can dress a salad decently although every one pretends to the art. A good salad mixer must have the poetry of nature in his bosom a keen eye to the beauty and the fitness of the materials a steady hand and delicate touch… Some author has said that it was as difficult to mix a good glass of punch or dress an eatable salad as it was to write a good epic poem and he is right. What is more disgusting than a bowl full of greasy vegetables with the unincorporated egg and the affronted mustard hanging in nasty clots upon the dabby flabby leaves while the sprightly self willed acid runs trickling over the conglomeration but refuses to mix with his abused comates? Culinary chemistry cannot achieve a higher triumph than a correct salad in which the ingredients kindly coalesce and the plants are covered with a cream like liquid possessing every possible quality without any preponderating taste.

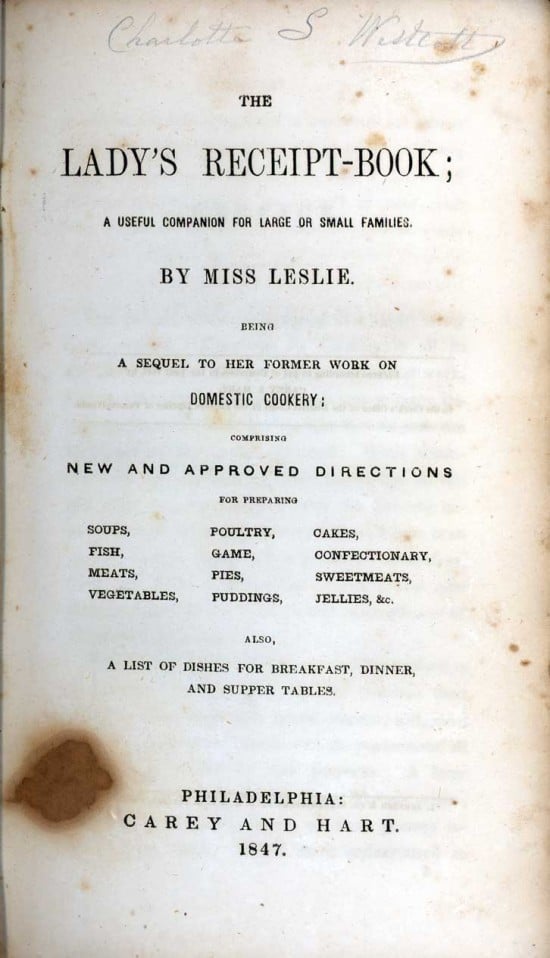

By mid-century, the democratic impulses of popular American cookbooks like Eliza Leslie’s The Lady’s Receipt-book (1847) had the dressings prescriptively matched up with each salad. No longer would Americans be permitted to wander in the salad wilderness, higgledy piggledy throwing together whatever caught their fancy and putting it on their greens. Salad dressing was about to be domesticated.

Towards the end of the century the mainstream-ization of salad and salad dressing accelerated. Auguste Escoffier shifted cuisine from the mansions of “royal” chefs like Marie-Antoine Carême to the restaurants of the rapidly expanding middle class. Escoffier also added mayonnaise and vinaigrette to his list of “mother” sauces (sauces that, with additions, spawn multitudes of adorable baby sauces) and codified the five types of salad dressing (see Le Guide Culinaire, 1903) and how and when to serve them. By the way, they are: Vinaigrette, cream, egg or mayonnaise, hot bacon (which I see altogether too little of), and mustard cream.

At the same time, sprawling hotels were being built all over the U.S. and following the unparallelled success of the Waldorf salad (created sometime between 1893 when the hotel opened and 1896 when their first cookbook was published with the recipe), they all seemed to lead with salad. Mainstays like the Cobb, Caesar, Green Goddess, Russian, Thousand Island, and the wedge salad all date from this period, and all except the wedge can be traced back to a specific hotel. Because of this branding, certain dressings became associated intimately with certain salads.

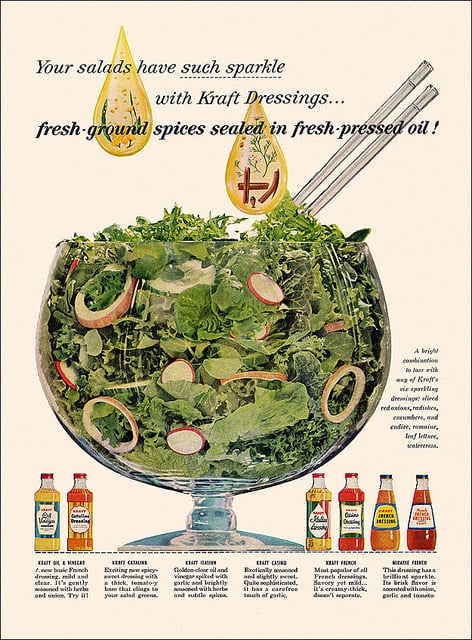

As the 20th century progressed, herb packets meant to be mixed with oil and vinegar started to replace free range dressing, and shelf stable formulations of cream dressings put the stake to those as well. Somewhere along the way, vinaigrette became Italian, French dressing got ketchup in it, and ranch took over America. And somehow the democratic impulses of American cookery, bringing recipes for ordinary food to the masses (and Escoffier’s upscale yet decidedly democratic freeing of cookery from the clutches of haute cusine), conspired to kill the free-wheeling, fun-loving salad dressing that had flounced around the planet for the better part of five millenia without being captured.

Every salad has a dressing; it is the opposite of choice, the warped, morbidly obese, mirror of what dressing had always been in this cold, cold world, so rich in lettuce yearning to be dressed. Worse, additives to bottled dressing have warped our ideas of what oil and vinegar should even look like.

Xantham gum was developed during the cold war by the US Department of Agriculture, commercialized during the 1960s, just after the Cuban Missile Crisis, and greenlighted for food use in 1968 — shortly before the Apollo 11 mission. It immediately became the thickener of choice for a wide variety of products, and is widely credited with stretching the viscosity gap to levels that the Kremlin, still smarting from our theft of Russian dressing in the aftermath of the revolution, found decidedly uncomfortable.

What resulted in the U.S. was even more troubling: a near universal expectation on the part of the American public for food items, especially salad dressing, that was unusually, unnaturally viscous. As a nation we now have expectations for emulsions that are completely untenable (not to mention that they all, whether appropriate or not, have sugar in them). Looking for widespread mind control perpetrated by the government of the United States? Well, keep looking, maybe you’ll find something great, but at least put a pin in this, because you really have to ask yourself: Why did the United States Government want everything to be so thick?

Vinaigrette is supposed to be a temporary emulsion — shake it up, put it on your salad, put it back on the table, it should separate into oil and vinegar long before you hit dessert. The expectation of a certain thickness, along with the sugar (and corn syrup) content of bottled dressing (people remain unlikely to add sugar to handmade dressings, even when they might benefit from it) make a return to the golden age of pre-domesticated salad extremely difficult. Even the “make it yourself” packets that you add oil and vinegar to have xantham gum and sugar in them. Not that there’s anything wrong with xantham gum — as bacteria-derived polysaccharides go, it’s terrific — but all it does is take the place of a little shaking.

Ironically, about the only dressing made in homes with any degree of frequency is balsamic vinaigrette. Made — this is the ironic part — with fraudulent, caramel-colored, heavily sugared, “balsamic vinegar”.

So here we are today, oppressed by our salad dressing “choices.” Stand in the salad dressing aisle at the grocery store and tell me you don’t feel oppressed — watched, even. Salad dressing, once a way for humanity to control our salad is now controlling us, bossing us around. Where did the bourgeoisie put all that coercion? Just follow the money and pour it on — you don’t even have to shake it.

It will be a long road back, but every time you pour some fish sauce on a green salad, shake some oil and vinegar together with whatever happens to catch your eye in the spice cabinet, every time you make some mayonnaise, mix it together with some ketchup, some hot peppers and garlic and say “take that Stalin, you bastard,” you reclaim just a little of what was stolen from us and thrown down that yawning chasm at the crossroads of democracy and capitalism.

MORE CONDIMENTS: Series Introduction | Fish Sauce | Diagram of Condiments vs. Sauces, etc. | Hot Sauce | Vinegar | Drunken Vinegar | Balsamic Vinegar | Food History | Barbecue Sauce | Butter | Mustard | Sour Cream | Maple Syrup | Salad Dressing | Gravy

STUFFED SERIES: THE MAGAZINE OF TASTE | AUGURIES AND PIGNOSTICATIONS | THE CATSUP WAR | CAVEAT CONDIMENTOR | CURRIE CONDIMENTO | POTATO CHIPS AND DEMOCRACY | PIE SHAPES | WHEY AND WHEY NOT | PINK LEMONADE | EUREKA! MICROWAVES | CULINARY ILLUSIONS | AD SALSA PER ASPERA | THE WAR ON MOLE | ALMONDS: NO JOY | GARNISHED | REVUE DES MENUS | REVUE DES MENUS (DEUX) | WORCESTERSHIRE SAUCE | THE THICKENING | TRUMPED | CHILES EN MOVIMIENTO | THE GREAT EATER OF KENT | GETTING MEDIEVAL WITH CHEF WATSON | KETCHUP & DIJON | TRY THE SCROD | MOCK VENISON | THE ROMANCE OF BUTCHERY | I CAN HAZ YOUR TACOS | STUFFED TURKEY | BREAKING GINGERBREAD | WHO ATE WHO? | LAYING IT ON THICK | MAYO MIXTURES | MUSICAL TASTE | ELECTRIFIED BREADCRUMBS | DANCE DANCE REVOLUTION | THE ISLAND OF LOST CONDIMENTS | FLASH THE HASH | BRUNSWICK STEW: B.S. | FLASH THE HASH, pt. 2 | THE ARK OF THE CONDIMENT | SQUEEZED OUT | SOUP v. SANDWICH | UNNATURAL SELECTION | HI YO, COLLOIDAL SILVER | PROTEIN IN MOTION | GOOD RIDDANCE TO RESTAURANTS.