The People of the Ruins (9)

By:

July 19, 2012

HILOBROW is pleased to present the ninth installment of our serialization of Edward Shanks’ The People of the Ruins: A Story of the English Revolution and After. New installments will appear each Thursday for 16 weeks.

Trapped in a London laboratory during a worker uprising in 1924, ex-artillery officer and physics instructor Jeremy Tuft awakens 150 years later — in a neo-medieval society whose inhabitants have forgotten how to build or operate machinery. Not only have his fellow Londoners forgotten most of what humankind used to know, before civilization collapsed, but they don’t particularly care to re-learn any of it. Though he is at first disconcerted by the failure of his own era’s smug doctrine of Progress, Tuft eventually decides that post-civilized life is simpler, more peaceful. That is, until northern English and Welsh tribes threaten London — at which point he sets about reinventing weapons of mass destruction.

Shanks’ post-apocalyptic novel, a pessimistic satire on Wellsian techno-utopian novels, was first published in 1920. In October, HiLoBooks will publish a beautiful new edition of The People of the Ruins, with an introduction by Tom Hodgkinson.

SUBSCRIBE to HILOBROW’s serialized fiction via RSS.

LAST WEEK: “‘Yes, yes,’ the Speaker murmured, ‘you may all be blown up. But there…’ He drew Jeremy by the shoulder into the corridor, and both their faces came into the shadow.”

ALL EXCERPTS: 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 |15 |16

MARCHING OUT

The nightmare settled again around Jeremy with a double darkness and bewilderment. Again he labored in the work-shops with his octogenarian assistants, but this time at first under a new oppression and a new hopelessness. Yet in some ways his mind was easier since he had understood that the frenzied haste which the Speaker urged on him was not urged without reason. After the council of war, the terrible old man, still jubilant, still strung up to the highest pitch of nervous energy, opened his mind to Jeremy without reserve. Jeremy, alarmed by his shining eyes, his feverish manner, his wild and abrupt gestures, still could not help seeing that his discourse was that of a sane man, a practical statesman, who was putting all he had on a single throw because there was no other choice.

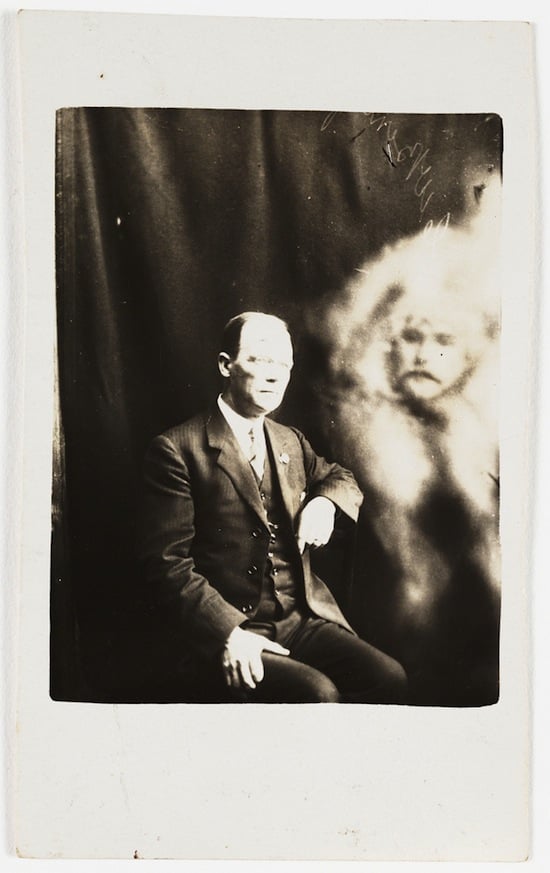

“My family has ruled without dispute,” the Speaker said, “for a hundred years — and that is a long time. We had no position, we merely stepped into the place of the old government, and the people let us because they were so tired. They obeyed us because they had been in the habit of obeying us, when there was no one else for them to follow. But we were not chosen, and we are too new to claim divine right. We cannot even look to our religion for support, because the country is divided. We here in the south are mostly by way of being Catholics, but though the Holy Father would give us his help, we have never dared to accept it. They are violent Methodists in Wales, and in Yorkshire and the north they are nearly all Spiritualists.”

Jeremy inquired with interest what this new religion might be; but the Speaker could only describe it as it existed, and then but vaguely. He could not give the history of its growth. Jeremy gathered that the Spiritualists still called themselves Christians, but depended much less on the ministrations of any church than on advice received in various grotesque ways from departed friends and relatives. Their creed seemed to have degenerated into a gloomy and superstitious form of ancestor-worship. They had absorbed also, he guessed, some of the tenets of what had been called Christian Science; and the compound had produced a great many extravagant manifestations. The Spiritualists owned no law or discipline in the spiritual world, but acted on the latest intelligence received from the dead. Most of them held firmly that evil was a delusion, a doctrine which had come to have a strange influence on conduct. All of them believed without a question in the future life; and the absolute quality of their belief, the Speaker thought, had gradually changed among them the distaste for fighting which at one time possessed the whole country. It would further, he thought, make them formidable soldiers. The picture he drew of them, still living in the decay of an industrial system, packed close amid the ruins of the old towns in a bleak country, dismayed and repelled Jeremy. The Speaker’s discourses did not fail of their intended effect. The listener began to believe that this enemy must be opposed at all risks.

“And you,” the Speaker said earnestly, as Jeremy rested for a moment in the workshop, “you shall have your reward. I have no son and I have a daughter.” He muttered the last sentence so much under his breath that it seemed he wished Jeremy not so much to hear it as to overhear it.

Jeremy’s mind had been elsewhere; and it was a minute or two before the sense of these words penetrated to him. When it did, it brought him sharply back to the actual world. But he did not speak at once. His natural caution interposed, his natural diffidence bade him consider.

“What do you mean by that?” he asked quietly after an interval.

“What I say,” the Speaker answered. “If you succeed in what you have to do, you shall be rewarded. If you don’t succeed, I shall not be able to reward you, even if I wish to.”

Jeremy desired very strongly to point out that this was unjust, that whether the guns would be a decisive factor in the coming battle depended almost entirely on chance. But he refrained. He refrained, too, from asking the Speaker precisely where the Lady Eva came into the scheme. Fortune appeared to him like a great, glittering bubble, which a miracle might make solid at the proper time for his hand to seize it. He dared not question further: he dared not think how much he was influenced by the Speaker’s determination not to consider the consequences of defeat.

And as that crowded week wore on, his mind settled into a sort of calm, like the apparent quietness of a wheel revolving at high speed. That would be which was written. In his anxiety to be sure that there was an adequate supply of shells (he did not hope to have more than thirty for each gun) he quite forgot that one of them might suddenly blow him into eternity, together with all the Speaker’s chance of success.

A great part of his time in the workshops was now spent alone — alone, that is to say, as far as the Speaker was concerned, for the old man was busy at the Treasury, mustering his army and making ready for it to march. As for the octogenarians, Jeremy felt little more kinship with them than if they had been a troop of trailed animals. Communication with them was so difficult that he confined it to the most necessary orders. But when he realized that these ludicrous old men would have to come with him to the battlefield to fire the guns, for want of time to train others, he began to feel for them a kind of compassionate affection. He regarded them rather as he would have done the horses of the gun-teams than as the men of his battery; but towards the end of the week he found himself talking to them, quite incomprehensibly, as he might have done to horses. It seemed to him pathetic that these witless veterans should be led out to war and set to the highly hazardous venture of firing off the guns they had themselves manufactured.

So, between the hours which he devoted to elementary instruction in loading, aiming, and firing, he gave to them his views on the situation in which he found himself. His views were, by reason of fatigue, strong emotions and bewilderment, of a confused and even childish sort. He told Jabez, the wizened expert in explosives, the whole story of Trehanoc’s dead rat — a story which, brief as it was, covered more than a hundred and seventy years. He confided to Jabez his desire, his impossible craving, to see the rat again. It was perhaps a little ridiculous to hanker so much after the society of a rather unpleasant animal. Nevertheless he and the rat were in the same boat, and in his more light-headed moments he felt that he ought to seek it out and take counsel with it. He was sure that the rat would understand. At other times he had a suspicion that it would have adjusted itself much more easily to the changed world than he could ever hope to do. Perhaps it had not even noticed that there had been any change. Jabez, wrinkled, skinny and toothless, listened complacently while he went on fumbling with his work, never letting a sign appear to show whether he did or did not understand a word of it. Jeremy reflected that it was perhaps better to be quite incomprehensible than to be half understood.

At the end of the week, on the afternoon of the sixth day, he decided that all was done that could be hoped for. He put the gun-crew again through its drill, and desisted for fear of scaring away what little sense its members still retained. Then, after overhauling the guns once more, he returned to the Treasury to report to the Speaker that he was ready.

As he entered the building he met the Lady Eva, who had just come in from riding. His mind was too dull and heavy to respond even to the sight of her vigorous, flushed beauty. He merely saluted her — he had queerly taken in the last few days to using again the old artillery salute — and would have gone on. But he saw her hesitate and half turn towards him; and he stopped and faced her. But when he had done so, she evidently did not know what to say to him. She stood there, tapping her foot on the ground and biting her lip, while he waited, bowed, lethargic, incapable of speech.

At last she said, with a jerky effort: “I do not know how my father is expecting you to save us… but I know that he is….”

He wondered whether this was the attempt of a frivolous girl to get news to which she had no right. He inclined his head gravely and made no reply.

She went on, still with an obvious effort: “I know he is… and I wanted to wish you success, and that — that no accident may happen to you.”

“I hope for all our sakes that there will be no accident,” he answered wearily, “but you never know.” He waited a few moments; but she seemed to have nothing more to say. He saluted her again and left her, continuing his slow way to the Speaker’s room. He did not see that she stood there looking after him until he was out of sight.

“We’re all ready,” he said tersely, as he entered.

“Then everything is ready,” the Speaker replied from his desk, where, with his clerk standing by his side, he was signing documents with great flourishes of a quill. “And it’s only just in time.”

“Only just in time?”

The Speaker dismissed the clerk and turned to Jeremy. “Only just in time,” he repeated, with an expression of gravity. “They have moved much quicker than I expected. They held up a train last week as soon as their messengers got back, and they’ve been bringing up troops in it nearly as far as Hitchin. Luckily it broke down before they had quite finished, and so the line is blocked. But the advance-guard I sent out met some of their patrols just outside St. Albans this morning.”

“Then the fighting has begun?” Jeremy asked, with a little excitement.

“Yes — begun.” The Speaker’s face was dark and sullen. “A hundred of our men were driven through the town by a score or so of theirs. They are moving on London already, but now they are coming more slowly than they have been. I intend to set out to-night and we shall meet them to-morrow somewhere on the other side of Barnet. They will come by the Great North Road.”

Jeremy was silent, and the Speaker came to him and took his arm. “Yes, Jeremy,” he said, with almost tenderness in his voice, “by this time to-morrow it ought to be all over.”

“But if they beat us,” Jeremy cried, “they will be into London at once. Haven’t you made any preparations? Won’t you send the Lady Burney and the Lady Eva somewhere in the south where they will be safe? I met the Lady Eva just now — she is still here —” He stopped and gulped.

“I will not,” said the Speaker, his voice deepening and taking on the resounding, the courageous, the mournful tones of a trumpet. “If we are beaten, then it is all over, and there is no need for us to look beyond defeat. If we are beaten, I do not care what happens to me or to you or to any one that belongs to me. For our civilization, that I have worked so long to maintain, would be dead, it would be too late to save England from savagery, and it would be better for all of us to die. Go now and see that your guns are ready to move in three hours. The horses will be there in time.”

Jeremy hesitated, reluctantly impressed by the old man’s solemn fervor. Then, without a word, he left the room and returned to the workshop.

As the end of the summer day faded and grew cooler, the Lady Eva sat with her mother and their attendants in a window of the Treasury overlooking Whitehall. The Lady Burney, who had long abandoned the practice of reading, was yet in the habit of hearing long stories and romances from clever persons who got them out of books; and she judged from what she had learnt of wars in the old times that it would be proper to her position to sit in a window and smile graciously on the army as it marched out to battle. It was an unfortunate thing that the Speaker, ignorant of her intentions and careless of the ritual of conflict, had appointed various places of assembly for the troops, and had taken no pains to make any part of them march through Whitehall. Detached bodies went by at intervals; and some of them, who chanced to look up, saw fluttering handkerchiefs. But most of them marched doggedly and dully with drooping heads, reflecting in their courage the prevailing spirit of gloomy anxiety which had settled on London.

Once a small erect figure on horseback clattered suddenly out of the Treasury almost immediately underneath, struggling with a wildly curvetting mount. The Lady Burney bowed and waved to it graciously. The girl Mary began and checked a sharp sigh of admiration. The Lady Eva sat motionless and expressionless. But Thomas Wells, impatient annoyance apparent in the line of his back, as soon as he had mastered the restive horse, trotted off, without once looking up, in the direction of Piccadilly, where he was to join the Speaker.

The light grew less and less, the sky became paler, with a curious and depressing lividity, as though the day were bleeding to death. The sound of marching troops, never very great or very frequent, came to the listeners in the window less often and less loud. A cloud of impalpable sadness fell upon the city and affected the Lady Eva like a spiritual miasma. The streets were not, in truth, quieter or emptier than was usual at nightfall: there was no outward sign that the people guessed at an approaching calamity. But there rose from all the houses a soft, deadening air of gloom. It was as though London had the heavy limbs, the racked nerves, the difficult breathing of acute apprehension. The Lady Eva could feel, and dumbly shared, the general oppression. She wished to leave the window, to take refuge amid lights and conversation from the creeping chill. But her mother, obstinate and sullen, dully incensed by the failure of her romantic purpose, insisted on staying, and made the rest stay with her.

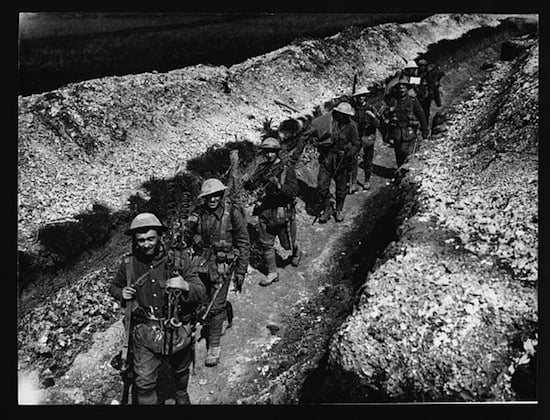

Just when the day was changing from a pale light shot with shadow into the first darkness of evening, they heard a loud clattering in Whitehall, a little way out of sight; and presently a long, slow procession came by, made up of obscure, grotesque shapes, hidden or rendered monstrous by the doubtful light. First there came a string of wagons, each drawn by two or four horses; and the men who walked beside them seemed to walk, or rather to hobble, with ludicrous awkwardness, all with bent backs and some leaning on sticks. At the end rolled two strange wheeled objects heavily swathed in tarpaulins, each drawn by a team of eight horses. The women in the window, tired of regarding the empty street for so long, gazed eagerly at these, but could not make out or give them a name. The Lady Eva alone sat back in her chair, hardly looking, until with a start she thought she saw a square, familiar figure riding beside the train on a horse as square and sedate as itself. Then she leant impulsively forward; but already Jeremy and his guns were swallowed up in the shades as they jogged along towards Charing Cross.

“Another baggage-train!” observed the Lady Burney, crossly and obesely, as she turned away from the window.

Jeremy had, in fact, looked up at the windows of the Treasury as he went by, and with a romantic thought in his head. But he, as little aware as the Speaker of the observances proper to the marching out of the army, had not expected to see any one there, and consequently saw no one. He merely reflected that the Lady Eva was somewhere behind those black walls; and he strove to lift away his depression by reminding himself that he was going to fight for her. But this exhortation had no effect on his anxious mind. The circumstances did not in the slightest degree alter an extremely difficult situation. It was merely one, even if the chief, of the factors which compelled him to face that situation, however unwillingly. It would not assist him to change the issue of a good old-fashioned infantry battle by means of two very doubtful sixty-pounder guns.

But this depression occupied only one part of his mind. With another he had got his column together at Waterloo, had seen to the effectual disguising of the guns, had marshalled the old men in their proper places and set out without misadventure or delay. The collapse of other means of crossing the river sent them round by Westminster Bridge, which shook and rumbled ominously under the weight of the guns, and thence along Whitehall in the direction of Charing Cross Road. Jeremy’s route had been indicated to him by the Speaker without the help of a map; but, to his surprise, he had been able to recognize the general line of it by means of the names. The column plodded slowly along a vile causeway that had been Tottenham Court Road into another as vile which was still called Euston Road, and, turning sharp to the right, made for the long hill which led towards Islington.

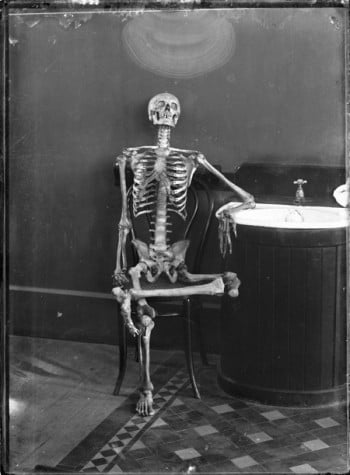

The mere marching through that shadowed and cheerless evening was depressing to Jeremy. He had chosen for his own use the fattest and least exuberant nag that the Speaker’s stables could offer him; and on this beast he cantered now and again to the head of the column and back, to see that all was well and to urge haste on the leaders. The old men were bearing it well. There was no doubt that they looked forward with a gruesome and repulsive glee to the use of their handiwork in action. As he rode by, Jeremy could see them hobbling cheerfully, cackling and exchanging unintelligible jokes in high, cracked voices. The gathering darkness and the changing shadows made them seem even more ghostly and grotesque. Jeremy shivered. He felt as though he were leading out against the living an army of the dead. But he mastered his repulsion and cried out encouragement, now to one, now to another, bidding them when they were tired to take it in turns to ride on the wagons. They answered him with thin cheers; and a few of them, marching arm-in-arm together, like old cronies released for an airing from the workhouse, set up a feeble but cheerful marching song.

As they topped the rise of the hill, the moon came up and revealed the uncanny desolation of the country through which they were moving. Here all was ruin, with partial clearings, like those which had been made in St. John’s Wood, only more extensive. The wide road had not been mended, yet had nowhere fallen into complete disuse, and was a maze of crisscrossing tracks and ruts, studded with pits which had here and there become little pools. Jeremy silently but fervently thanked the moon for rising in time to save his guns from being stuck in any of these death-traps. He rode by the first gun, watching the road anxiously; and he spent an agonized five minutes when one of the wagons in front slipped a wheel just over the edge of a pit and blocked up the only practicable way. The old men gathered around at once, cheering themselves on with piping cries, and at last heaved the wagon out. The column went slowly on — all too slowly, it seemed to Jeremy, who yet dared not make greater haste.

And then, in spite of his fears and his whirling brain, fatigue sent down on him a sort of numbing cloud. He drooped and nodded in the saddle, picking his way only by a still, vigilant instinct. Wild fancies and figures hurled themselves through his weary brain without startling him. Once he seemed to see the thin, animal face of the Canadian, teeth bared and a little open, painted on the darkness only a few inches from his eyes. Once as he lurched heavily it seemed that the arms of the Lady Eva caught him and steadied him and held him, and that he let fall his head on the delicious peace of her breast. He woke with a. start to see that the road forked and that the column was taking the road on the right. The moon was now high, and made his battery and the road and the few houses that were still standing here all black and silver. On his right stood a small ale-house, with open door, whence came the pale glow of a dying fire. It occurred to him that he must see to it that none of his old men straggled in here to rest or hide; and, pulling out of his place in the column, he rode towards it. As he did so he saw the sign on which the moonlight fell full and read with strange feelings the rudely-scrawled words, “The Archway Tavern.” He looked, with hanging lip and staring eyes, for the busy swing-doors of the public-house which had been a landmark and which he had passed he knew not how many times. Though he had never entered it, this simulacrum, this dwindled vestige on the place where of old it had stood, opulent, solid and secure, affected him like a memento mori, a grim epitaph, the image of a skull. It was a sudden and poignant reminder of the transiency of human things and of the strange nakedness of the age in which he now lived. When he turned away he was sitting limp and dazed in the saddle.

In an alternation of fits of such drowsiness and of vigorous, bustling wakefulness, Jeremy got his column slowly over the undulations of the Great North Road. The moon at last went down; and as morning approached, the sky grew cloudy and every spark of light vanished from the world. Then, at the moment they entered on the first rise of what Jeremy supposed to be Barnet Hill, a thin breeze began to blow from the east and to bring with it a faint radiance. Jeremy felt on his right cheek the wind and the light at once, light like wind and wind like light, both numbingly cold. And, as they came to the top of the hill, the sun rose and revealed to them the assembled army.

NEXT WEEK: “They were extravagantly keen to show the twenty-first century what their guns could do; but in their anxiety to take their place on the battlefield they behaved, as Jeremy bitterly though unintelligibly told them, like a crowd of children scrambling outside the door of a Sunday-school tea.”

RADIUM AGE SCIENCE FICTION: “Radium Age” is HILOBROW’s name for the 1904–33 era, which saw the discovery of radioactivity, the revelation that matter itself is constantly in movement — a fitting metaphor for the first decades of the 20th century, during which old scientific, religious, political, and social certainties were shattered. This era also saw the publication of genre-shattering writing by Edgar Rice Burroughs, Sax Rohmer, E.E. “Doc” Smith, Jack London, Arthur Conan Doyle, Aldous Huxley, Olaf Stapledon, Karel Čapek, H.P. Lovecraft, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Yevgeny Zamyatin, Philip Gordon Wylie, and other pioneers of post-Verne/Wells, pre-Golden Age “science fiction.” More info here.

HILOBOOKS: The mission of HiLoBooks is to serialize novels on HiLobrow; and also, as of 2012, operating as an imprint of Richard Nash’s Cursor, to reissue Radium Age science fiction in beautiful new print editions. So far, we have published Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague, Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”), Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt, H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook, Edward Shanks’s The People of the Ruins, William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land, and J.D. Beresford’s Goslings. Forthcoming: E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man, Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage, and Muriel Jaeger’s The Man with Six Senses. For more information, visit the HiLoBooks homepage.

READ: Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague, serialized between January and April 2012; Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”), serialized between March and June 2012; Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt, serialized between April and July 2012; and H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook, serialized between March and August 2012.

ORIGINAL FICTION: HILOBROW has serialized three novels: James Parker’s The Ballad of Cocky The Fox (“a proof-of-concept that serialization can work on the Internet” — The Atlantic) and Karinne Keithley Syers’s Linda Linda Linda. We also publish original stories and comics.