Nomadbrow (10)

By:

July 10, 2012

Erik Davis, author of Techgnosis, Nomad Codes, [Led Zeppelin IV], and Visionary State, is a friend of HiLobrow. He is also a contributor: His 2010 “Pop Arcana” column for us on the Cute Cthulhu meme remains one of our most popular posts. We’re thrilled to publish ten of Davis’s essays which first appeared elsewhere; this is the tenth installment in the Nomadbrow series.

The Scarecrow Replicant

In one of my favorite passages from the philosopher Slavoj Žižek, the slovenly Hegelian points to the difference that Lacan drew between “the subject of enunciation” and the “subject of the enunciated.” The basic notion is that there is a yawning gap between everything we can say about who we are and the empty, mute site from which such statements are launched. The positive “me” that I can describe and experience as a particular person with particular desires, thoughts, and memories is not the empty “I” who enunciates and temporarily identifies (or not) with this content. The cogito — Descartes’ “I think” — is crystal clear, but completely empty.

This distinction also comes up a lot in the more astringent flavors of spiritual inquiry, in which the disidentification with the self can serve as an opening to the shining void within. But it also pops up in pop culture. In an essay with the B-movie title “I or Her or It (the Thing) Which Thinks,” Žižek brings up the example of Blade Runner, a film whose complex of concepts and images I keep returning to year after year. The basic paradox that Žižek identifies is the “subject who knows he is a replicant.” If I am such a replicant who has awakened to my true nature, I must recognize that my body, my eyes, and even my most intimate memories and fantasies are artifacts. The “positive” material that seemed to compose my supposed humanity is thus cut off from me even though it is all the “me” I have.

The replicant paradox of course is also a model for the Lacanian split described above, in which biological humans discover the irreducible difference between the substantive me (all the stuff I do, my memories, my body) and the empty “I” of the cogito, the void that is constantly and hopelessly trying to ground itself. This split means that in an almost structural sense we are much less human than we conventionally think — in this light, “awakening to our true nature” may be identical with embracing our inner android. But the condition of the replicants in Blade Runner also gives us an insight into the specifically emotional dimension of this split, an emotion that paradoxically returns us to the authentically human. Here’s Žižek, tangled as usual:

The implicit thesis of Blade Runner is that replicants are pure subjects precisely insofar as they testify that every positive, substantial content, inclusive of the most intimate fantasies, is not “their own” but already implanted. In this precise sense, subject is by definition nostalgic, a subject of loss. Let us recall how, in Blade Runner, Rachel silently starts to cry when Deckard proves to her that she is a replicant. The silent grief over the loss of her “humanity,” the infinite longing to be or to become human again, although she knows it will never happen; or, conversely, the eternal gnawing doubt over whether I am truly human or just an android — it is these very undecided, intermediate states which make me human.

We are already lost to our positive humanity, and yet the awakening to that condition, in its longing and mourning and insight into our condition, renders us, or the replicants, paradoxically human.

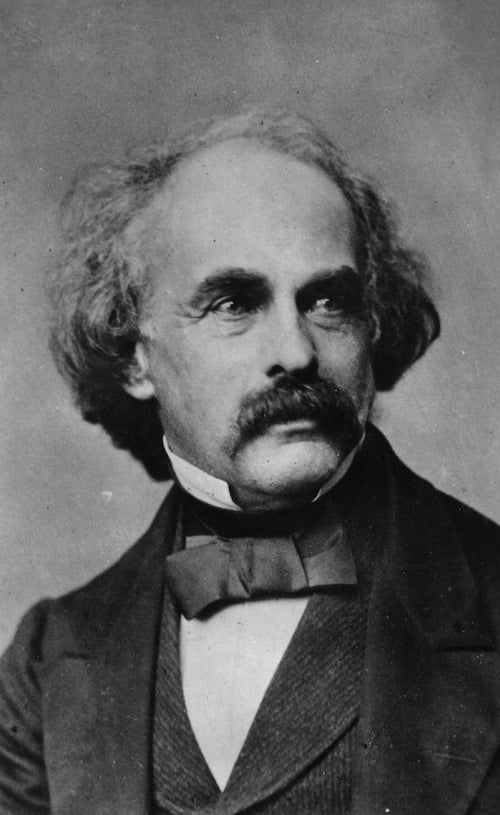

That’s a nifty posthuman koan, one worth keeping in mind as we navigate the contemporary mind-field of cognitive enhancements, self-data-mining, and cyborg tech. But imagine my surprise and delight when I stumbled across almost the same affective concept in a Nathaniel Hawthorne short story published in 1852.

I have been reading a lot of Hawthorne’s tales and sketches of late — he is a remarkable stylist, and his gloom and anxiety and gothic twists and turns seem to offer an enchanted path into aspects of American consciousness that seem more pressing in our time than, say, the rival darkness of Poe. One complaint with Hawthorne is that the narrative form of the stories are pretty predictable, even conservative — the tales are openly allegorical, and it only takes a few pages for the reader to figure out the “meaning,” and thus the inevitable narrative culmination of the tale. This is bad form as far as modernist sensibility goes. We expect fiction to surprise us with its twists and turns, or at least to not give away its end, and point, so obviously.

On the other hand, many of us continue to relish the stories of H.P. Lovecraft, another New England brooder, and a writer who loved and was influenced by Hawthorne. Though Lovecraft is not allegorical, his stories often encourage the reader to perceive the existence of supernatural evil much sooner than the main character. As with Hawthorne, much of the reading experience consists of waiting for the character to catch up, and to realize something that we have already figured out. I think this shared formal element between Lovecraft and Hawthorne has something to do with the Calvinist strain of American Puritanism, whose long shadow of predestination even cast itself upon the rationalist and nihilist Lovecraft (not to mention Pynchon, or the poet Jack Spicer, who wrote, in 1965, “Mechanically we move / In God’s Universe, Unable to do / Without the grace or hatred of Him”). After all, if the story has already been written, if the elect are the elect and the preterite are the preterite, then their stories too will seem, to the reader, already completed, already set in stone, with no more twists and turns than a knowing nod of the head.

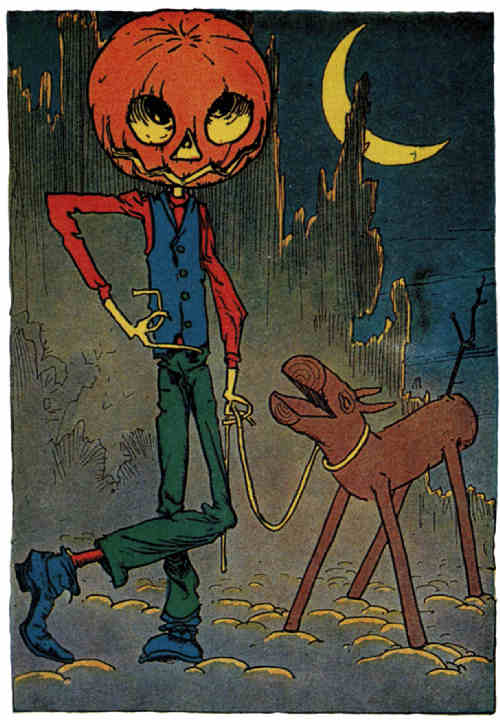

The Hawthorne allegory I was reading was “Feathertop: A Moralized Legend.” In the tale, an old witch named Mother Rigby builds a scarecrow out of ruined clothes, sticks, and a pumpkin. She then puts a glamour on the stickman so that he appears to be a human being — and a particularly noble and well-dressed one at that. (The magic that keeps the scarecrow looking human is delightful: he must constantly puff tobacco smoke through his fancy meerschaum pipe.) The scarecrow Feathertop is a Calvinist android: a determined thing with a charismatic illusion of agency. Following the witch’s directions, Feathertop seeks out a pretty lass who he begins to woo in her parlor room. As she is falling in love with him, the girl turns to the mirror and sees Feathertop’s true form in the reflection of the glass. She faints, and then Feathertop turns and sees the same stark truth:

The wretched simulacrum! We almost pity him. He threw up his arms with an expression of despair that went further than any of his previous manifestations towards vindicating his claims to be reckoned human; for, perchance the only time since this so often empty and deceptive life of mortals began its course, an illusion had seen and fully recognized itself.

It is not only vampires who must beware the mirror, it seems. But from those scarecrow eyes some shard of humanity may linger, a sentiment of longing known only in reverse. Happy shaving, fellow pumpkinheads!

READ Erik Davis’s “Pop Arcana” series for HiLobrow.

CURATED SERIES at HILOBROW: UNBORED CANON by Josh Glenn | CARPE PHALLUM by Patrick Cates | MS. K by Heather Kasunick | HERE BE MONSTERS by Mister Reusch | DOWNTOWNE by Bradley Peterson | #FX by Michael Lewy | PINNED PANELS by Zack Smith | TANK UP by Tony Leone | OUTBOUND TO MONTEVIDEO by Mimi Lipson | TAKING LIBERTIES by Douglas Wolk | STERANKOISMS by Douglas Wolk | MARVEL vs. MUSEUM by Douglas Wolk | NEVER BEGIN TO SING by Damon Krukowski | WTC WTF by Douglas Wolk | COOLING OFF THE COMMOTION by Chenjerai Kumanyika | THAT’S GREAT MARVEL by Douglas Wolk | LAWS OF THE UNIVERSE by Chris Spurgeon | IMAGINARY FRIENDS by Alexandra Molotkow | UNFLOWN by Jacob Covey | ADEQUATED by Franklin Bruno | QUALITY JOE by Joe Alterio | CHICKEN LIT by Lisa Jane Persky | PINAKOTHEK by Luc Sante | ALL MY STARS by Joanne McNeil | BIGFOOT ISLAND by Michael Lewy | NOT OF THIS EARTH by Michael Lewy | ANIMAL MAGNETISM by Colin Dickey | KEEPERS by Steph Burt | AMERICA OBSCURA by Andrew Hultkrans | HEATHCLIFF, FOR WHY? by Brandi Brown | DAILY DRUMPF by Rick Pinchera | BEDROOM AIRPORT by “Parson Edwards” | INTO THE VOID by Charlie Jane Anders | WE REABSORB & ENLIVEN by Matthew Battles | BRAINIAC by Joshua Glenn | COMICALLY VINTAGE by Comically Vintage | BLDGBLOG by Geoff Manaugh | WINDS OF MAGIC by James Parker | MUSEUM OF FEMORIBILIA by Lynn Peril | ROBOTS + MONSTERS by Joe Alterio | MONSTOBER by Rick Pinchera | POP WITH A SHOTGUN by Devin McKinney | FEEDBACK by Joshua Glenn | 4CP FTW by John Hilgart | ANNOTATED GIF by Kerry Callen | FANCHILD by Adam McGovern | BOOKFUTURISM by James Bridle | NOMADBROW by Erik Davis | SCREEN TIME by Jacob Mikanowski | FALSE MACHINE by Patrick Stuart | 12 DAYS OF SIGNIFICANCE | 12 MORE DAYS OF SIGNIFICANCE | 12 DAYS OF SIGNIFICANCE (AGAIN) | ANOTHER 12 DAYS OF SIGNIFICANCE | UNBORED MANIFESTO by Joshua Glenn and Elizabeth Foy Larsen | H IS FOR HOBO by Joshua Glenn | 4CP FRIDAY by guest curators