The People of the Ruins (7)

By:

July 5, 2012

HILOBROW is pleased to present the seventh installment of our serialization of Edward Shanks’ The People of the Ruins: A Story of the English Revolution and After. New installments will appear each Thursday for 16 weeks.

Trapped in a London laboratory during a worker uprising in 1924, ex-artillery officer and physics instructor Jeremy Tuft awakens 150 years later — in a neo-medieval society whose inhabitants have forgotten how to build or operate machinery. Not only have his fellow Londoners forgotten most of what humankind used to know, before civilization collapsed, but they don’t particularly care to re-learn any of it. Though he is at first disconcerted by the failure of his own era’s smug doctrine of Progress, Tuft eventually decides that post-civilized life is simpler, more peaceful. That is, until northern English and Welsh tribes threaten London — at which point he sets about reinventing weapons of mass destruction.

Shanks’ post-apocalyptic novel, a pessimistic satire on Wellsian techno-utopian novels, was first published in 1920. In October, HiLoBooks will publish a beautiful new edition of The People of the Ruins, with an introduction by Tom Hodgkinson.

SUBSCRIBE to HILOBROW’s serialized fiction via RSS.

LAST WEEK: “You are happier than we were,” he said, “though you are poorer. Your air is clean, you have room, you live at peace, you have time to live. But we were forced to live in thick, smoky air; we fought and quarreled, and disputed. The more difficult our lives became, the less time we had for them.”

ALL EXCERPTS: 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 |15 |16

THE LADY EVA

The Speaker’s reception was a gorgeous and tedious assembly, held in the afternoon for the better convenience of a society which had but indifferent resources in the way of artificial light. A great hall in the Treasury had been prepared for it; and here the “big men,” and their wives and sons and daughters, showed themselves, paid their respects to the Speaker and to the Lady Burney, paraded a little, gathered into groups for conversation, at last took their leave.

Jeremy walked through the crowd at the Speaker’s elbow and was presented by him to the most important of the guests. This was a mark of favor, of recognition, almost of adoption. He had at first been afraid of it and had wished to avoid it. But the Speaker’s determination was unalterable.

“If it were nothing more,” he said, with a contemptuous smile on his heavy but mobile mouth, “I shall be giving them pleasure by exhibiting you. You are a show, a curiosity to them. They are all longing to see you — once…. Only you and I know that you are something more. And to know it pleases me; I hope it pleases you.”

This explanation hardly reconciled Jeremy to the ordeal; but the Speaker had easily overborne his reluctance. They walked through the room together, a couple strangely unlike; and the old man showed towards the younger all the tenderness, all the proud complaisances of a father to a son.

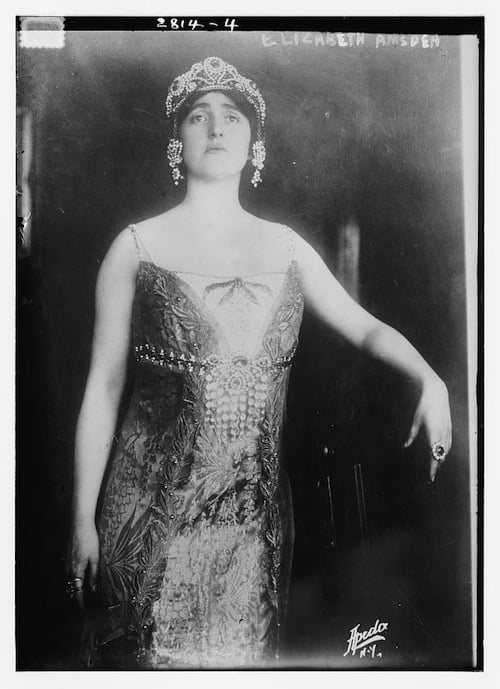

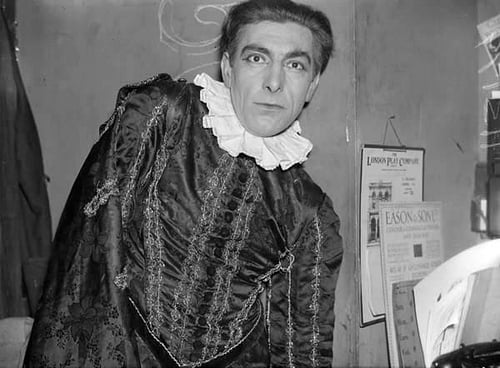

From this post of vantage Jeremy could at least see all that was to be seen. The assembly seemed to be gay and animated. The men wore the dress of ceremony, the latter-day version of evening dress; and some of them, especially the more youthful, were daring in the colors of their coats and in the bravado of lace at throat and breast and wrist. The women wore more elaborate forms of the gown of every day, simply cut in straight lines, descending to the heel and tortuously ornamented with embroideries in violent colors. Jeremy saw one stout matron who was covered from neck to shoes in a pattern of blowsy roses and fat yellow butterflies, like a wall-paper of the nineteenth century, another whose embroidery took the shape of zigzag stripes of crimson, blue and green, adjoining on the bodice, separated on the skirt.

But he was impressed by a certain effect of good breeding which their behavior produced and which contradicted his first opinion, based on the strangeness of their dress. They nodded to him (for the shaking of hands had gone quite out of fashion), stared at him a little, asked a colorless question or two, murmured politely on his reply, and drifted away from him. Where he expected crudity and vulgarity, he found a prevailing vagueness, tepidity, indifference, almost fatigue…. He was forced to conclude that the flamboyancy of their appearance was mild to themselves, that they had no wish to appear startling, and did so only as the result of a universal lack of taste.

He moved among them, steadfastly following the Speaker, but feeling tired and stiff and inert. His limbs ached with unaccustomed labor, his left hand was torn and bandaged, and he had still in his nostrils the thick, greasy smell of the workshops in which he had spent the morning. Here, after his first shock of surprise at the sight of the guns, he had soon understood that he was expected to do much more than admire and approve. These, the Speaker said, were by no means his first experiments in the art of gun-casting. And, after that, the old man had recounted to Jeremy, assisted by occasional uncouth ejaculations from the aged foreman of that amazing gang of centenarians, a story that had been nothing less than stupefying.

The last men in whose fading minds some glimmer of the art still remained had been gathered together, at the cost of infinite trouble, from the districts where machinery was still most in use, chiefly from Scotland, Yorkshire, and Wales. They had been brought thither on the pretense that their experience was needed in the central repairing-shops of the railways; and apparently it had been necessary in all possible ways to deceive and to reassure the principal men of their native districts. Once they had been obtained, they had slaved for years with senile docility to satisfy the demands which the Speaker’s senile and half-lunatic enthusiasm made on their disappearing knowledge. Somehow he had created in them a queer pride, a queer spirit of endeavor. That grotesque chorus of ancients had become inspired with a single anxiety, to create before they perished a gun which could be fired without instantly destroying those who fired it.

They had had trouble with the breech-mechanism, the Speaker nonchalantly remarked; and Jeremy had a vision of men blown to pieces in the remote and lonely valley where the first guns were tried. The immediate purpose for which Jeremy’s help was required was the adjustment of the process of cutting the interrupted screw-thread by which the breech-block was locked into the gun. He had toiled at it all the morning, surrounded by jumping and antic old men, whose speech he could hardly understand and to whom he could only with the greatest exertion communicate his own opinions. He had wrestled with, and tugged at, antiquated and dilapidated machinery, had cursed and sworn, had given himself a great cut on the palm of his left hand and had descended almost to the level of his ridiculous fellow-workers. And yet, when he had finished, the difficult screw-thread was in a fair way to be properly cut.

He came hot from these nightmare experiences to the Speaker’s reception; and when he looked round and contrasted the one scene with the other, he had a sense of phantasmagoria that made him feel dizzy. It was almost too much for his reason… on top of a transition that would have overbalanced most normal men…. He was recalled from his bewildering reflections by the Speaker’s voice, low and grumbling in his ear.

They had drifted for a moment away from the thickest of the crowd into a corner of the room, and the old man was able to speak without fear of being overheard. “It is as I have noticed for years,” he said, “but it gets worse and worse. These are only from the south.”

Jeremy started and replied a little at random: “Only from the south…?”

“Listen carefully to all I say to you. It is all useful. These people here are only from the south, from Essex, like that young Roger Vaile, and Kent and Surrey and Sussex and Hampshire. The big men from the north and west come every year less often to the Treasury. And yet these fools hardly notice it, and would see nothing remarkable in it if they did.”

“You mean…” Jeremy began. But before he could get farther he-saw the Speaker turn aside with a smile of obvious falsity and exaggerated sweetness. The sinister little person, whom Jeremy knew from a distance as “the Canadian,” was approaching them with a characteristically arrogant step and bearing.

The Speaker made them known to one another in a manner that barely concealed a certain uneasiness and unrest. “Thomas Wells,” he explained in a loud and formal voice, “is the son of one of the chief of the Canadian Bosses, whom we reckon among our subjects and who by courtesy allow themselves to be described as such. But I reckon it as an honor to have Thomas Wells, the son of George Wells, for my guest in the Treasury.”

“That’s so,” said the Canadian gravely, without making it quite clear which part of the Speaker’s remark he thus corroborated. Then he stared keenly at Jeremy, apparently controlling a strong instinct of discomfort and dislike by an effort of will. Jeremy returned the stare inimically.

“I believe we have met before,” he suggested, not without a little malice.

“That’s so,” the Canadian agreed; and as he spoke he sketched the sign of the cross in an unobtrusive manner that made it appear as though it might have been a chance movement of his hand. The Speaker hung over them with evident anxiety, and at last said:

“You two are both strangers to this country. You ought to be able to compare your impressions.”

“I would much rather hear something about Canada,” Jeremy answered.

Thomas Wells shrugged his shoulders. “It isn’t like this country,” he said carelessly. “We can’t be as easy-going as the people are here. We have to fight — but we do fight and win,” he concluded, momentarily baring his teeth in a savage grin.

“The Canadians, as every one knows, are the best soldiers in the world,” the Speaker interpolated. “They are always fighting.”

“And whom do you fight?” Jeremy asked.

“Oh, anybody… You see, the people to the south of us are always quarreling among themselves, and we chip in. And then sometimes we send armies down to Mexico or the Isthmus.”

“But the people to the south…” Jeremy began. “Haven’t you still got the United States to the south of you? And I should have thought they’d be too many for you?”

“There are no United States now —I’ve heard of them.” Thomas Wells’s dislike of Jeremy seemed to have been overcome by a swelling impulse of boastfulness. “From what I can make out, they never did get their people in hand as we did. They’ve always been disturbed. Their leaders don’t last long, and they fight one another. And we’re always growing in numbers and getting harder, while they get fewer and softer. Why, they’re easy fruit!”

Jeremy could find nothing for this but polite and impressed assent. Thomas Wells allowed his lean face to be split by a startling grin and went on: “I suppose you’ve never heard of me? No! Well, I’m not like these people here. I was brought up to fight. My dad fought his way to the top. His dad was a small man, out Edmonton way, with not more than two or three thousand bayonets. But he kept at it, and now none of the Bosses in Canada are bigger than we are. It was me that led the raid on Boston when I was only twenty.”

Jeremy turned aside from the last announcement with a feeling of disgust. He thought that Thomas Wells looked like some small blood-thirsty animal, a ferret or a stoat, with pale burning eyes and thin-stretched mouth that sought the throat of a living creature. He, was saved from the necessity for an answer by the Canadian turning sharply on his heel, as though something had touched a spring in his body. Jeremy followed the movement with his eyes and saw the Lady Eva making her way towards them through the crowd.

Thomas Wells went to meet her with an air of exaggerated gallantry, and murmured something with his bow. She seemed to be to-day in a mood of modest behavior, for she received his salutation with downcast eyes and no more than a movement of the lips. As he watched them Jeremy again became aware of the Speaker standing beside him, whom he had for a moment forgotten. He stole a look at the old man and saw that his brow was troubled and that, though his hands were clasped behind his back in an apparently careless attitude, the fingers were clenched and the knuckles white. As he registered these impressions, the Lady Eva, still with downward glance, sailed past Thomas Wells and approached him. When he saw her intention, a faint disturbance sprang up in his heart and interfered with his breathing.

She had already halted beside him when he realized that now, in the presence of this company, her deportment being what it was, he must make the first speech. He stuttered awkwardly and said: “I have been hoping to see you again.”

She raised her eyes a trifle, and he fancied that he saw the shadow of a smile in the corners of her mouth. Her reply was pitched in so low a tone as to be at first incomprehensible, and there followed a moment of emptiness before he realized that she had said, “You have been with Roger Vaile.”

He interpreted it as in some sort of a reproach, and was about to protest when he saw the Speaker frowning at him. He did not understand the frown, but he moderated his vehemence. “I have been learning,” he said in level tones. “I have been learning a great deal.” And then he added more quietly, “Not but what you could teach me much more.”

At this she raised her head and laughed frankly; and he, looking up too, saw that the Speaker had drawn Thomas Wells away and that the backs of both were disappearing in the throng. A strange, uncomfortable sense of an intrigue, which he could not understand, oppressed him. He glared suspiciously at the girl, but read nothing more than mischief and merriment in her face.

“I was well scolded the last time I spoke to you,” she said, “but I have behaved well this time, haven’t I?”

Exhilaration chased all his doubts away. He gazed at her openly, took in the wide eyes, the straight nose, the sensitive mouth, the healthy skin. Then he tried to pull himself together, to recover a dry, sane consciousness of his situation. It was absurd, he told himself — at his age!— to be unsettled by a conversation with a beautiful girl who might have been, if he had had any, one of his remote descendants. He felt unaccountably like a man glissading on the smooth, steep slope of a hill. Of course, he would in a moment be able to catch hold of a tuft of grass, to steady himself by digging his heels into the ground… But meanwhile the Lady Eva was looking at him.

“What do you think I could teach you?” she asked.

“I know so little,” he answered haphazard. “I know nothing about any of the people here. I suppose you know them all?”

“They are the big men and their wives. What can I tell you about them?”

“What do you think of them yourself?”

She eyed him a little askance, doubtful but almost laughing. “What would you think… what would they think — if I were to tell you that?”

“But they will never know,” he urged, in a tone of ridiculously serious entreaty.

“Don’t you know that I am already considered a little… strange? I don’t think I could tell you anything about our society that would be any use to you. My mother tells me every day that I don’t know how to behave myself; and I daresay all these people would say the same.”

“But why?”

“Oh, I don’t know…” She half swung round, tapped the floor with her heel and returned to him, grown almost grave. “I hate the… the… the easiness of everybody. They all stroll through life, and the women do nothing and behave modestly — they’re not alive. I suppose I am like my father. He is odd too.”

“But I am like him,” Jeremy said earnestly. “If you are like him, then I must be like you. But I don’t know enough to be sure how different every one else is. They seem very amiable, very gentle….”

“I hate their gentleness,” she began in a louder tone. But instead of going on, she dropped her eyes to the ground and stood silent. Jeremy, perplexed for a minute, suddenly became aware of the Lady Burney beside them, an expression of dull disapproval on her brilliantly carmined face. He had the presence of mind to bow to her very respectfully.

“I am glad to see you again, Jeremy Tuft,” she said with a heavy and undeceiving graciousness. As she spoke she edged herself between him and the Lady Eva; and Jeremy could quite plainly see her motioning her daughter away with a gesture that she only affected to conceal. He strove to keep an expression of annoyance from his face and answered as enthusiastically as he could. She spoke a few more listless sentences with an air of fighting a rearguard action. When she left him he sought through the room for the Lady Eva, disregarding all who tried to accost him; but he could not come at her again.

Roger Vaile was divided between disappointment and pride at Jeremy’s favor with the Speaker, and expressed both feelings with the same equability of demeanor.

“I hope I shall see you again sometimes,” he said; “but the Speaker has always disliked me.”

Jeremy experienced an acute discomfort and sought to relieve himself by replying with warmth, “But you saved my life. I told him that you did.”

Roger shook his head and smiled. “Of course he took no more notice of that than I do. After all, it is rather absurd, isn’t it? I merely happened to be the first man that saw you. But I liked looking after you, and I should be sorry if I never saw you again. And so would my uncle.”

At the mention of the priest contrition assailed Jeremy. He had a vision of the old man desiring information about the twentieth century and not receiving it. Roger saw what was passing through his mind and again shook his head slightly.

“The Speaker thinks my uncle an old fool,” he went on reflectively, “and from some points of view he’s right. And he thinks me a young fool, which I shouldn’t presume to dispute. For that matter he things most people are fools. And the Lady Burney thinks I am a good-for-nothing young scoundrel — but she has her own reasons for that.”

“And what does the Lady Eva think of you?” Jeremy asked curiously.

“Oh, the Lady Eva’s a wonder!” Roger said with more fervor than he usually displayed. “She’s not like any one else alive. Why, do you know the other day, when she was out riding with her groom she beckoned to me and made me ride with her for ten minutes while I told her all about you.”

Jeremy supposed that this must be unusually daring conduct for a young girl of the twenty-first century, and he acknowledged the impression it made on him by nodding his head two or three times.

“That’s the chief reason why the Lady Burney hates me,” Roger continued, a slight warmth still charging his voice. “But she doesn’t understand her own daughter. The Lady Eva takes no particular interest in me. She merely can’t bear being cooped up, like other girls, and not being able to talk to any one she wants to. And because I’ve gone to her once or twice when she has called to me, they think there’s something between us. But there isn’t: I wish there were.”

Jeremy regarded with admiration this moderate and gentle display of passion. “But whom will she marry?” he ventured, feeling himself a little disturbed by his own question as soon as it was uttered.

“I believe the Lady Burney would like her to marry that horrible Canadian. And her father would marry her to any one if he saw his profit in it. It’s lucky for her that the Chairman of Bradford is married already.”

“What makes you say that?”

“He’s the biggest man of the North and one of the men, so they say, that the Speaker is most afraid of. There’s some kind of dispute going on between them now. But it’s all nonsense,” Roger concluded indifferently. “There’s really nothing for them to quarrel about and nothing will come of it. But the Speaker always does excite himself about nothing and always has. He’s a very strange old man; and the Lady Eva is like him in some ways. And then there’s that Canadian… You will find yourself among a queer lot: I own that I don’t understand them.”

But in spite of Roger’s wishes and Jeremy’s protestations their meetings were, for some time after this conversation, casual and infrequent. The Speaker, as he grimly said, had a use for Jeremy, and was determined to see it accomplished. Day after day they went together to the guarded and mysterious workshop behind Waterloo Station. There, day after day, Jeremy painfully revived his rusty knowledge of mechanics, and, himself driven by the Speaker, drove the gang of old men to feats of astonishing skill.

He was astonished at the outset to see what they had actually done. To have made two rifled, wire-wound guns, with their failing wits and muscles and with the crazy museum of machinery which they showed him, had been truly an amazing performance. He learnt later that this was the eleventh pair that had been cast in fifteen years, and the first since they had mastered the art of properly shrinking on the case. They were still in difficulties with the screw-thread inside the gun that locked the breech-block; and as he set them time and time again at the task of remedying this or that fault in their workmanship, he understood why they had taken so long and why so many guns had blown up. What he could not understand was the Speaker’s indomitable persistence in this fantastic undertaking, which, but for his own arrival in the world, might have taken fifteen years more and outlasted all the old men concerned in it.

But while he slaved, sweating and harassed, sometimes despairing because of a scrap of knowledge that evaded his memory or because of the absence of some machine that would have ensured accurate working, the Speaker hovered round him and, little by little, in long harangues and confessions, laid bare the mainsprings of his nature. These extraordinary scenes lasted in Jeremy’s mind, moved before his eyes, echoed in his ears, when he had left the shed, when he sat at dinner or in the darkness when he was trying to sleep, until he found that he was gradually being infected with a dogged, unreasoning enthusiasm like that of his dotard fellow-workers. He even felt a little ashamed of himself for succumbing to the fanatical influence of an insane old Jew.

But the Speaker would stand at his elbow, when he was adjusting a decrepit lathe that ought to have been long ago on the scrap-heap, and rhapsodize endlessly in his thick muttering voice that rose sometimes to a shout, accompanied by lifted hands and flashing eyes.

“I was born too late,” he would cry, “and I should perhaps have given up hope if I had not found you. But you and I, when this task is done, will regenerate the kingdom. How long I have labored and these easy-going fools have not once helped me or understood me! But now our triumph begins — when the guns are made.”

Jeremy, standing up to ease his back and wiping his hands on an oily rag, would reflect that if it took so long to cut a screw-thread correctly, the regeneration of the whole kingdom was likely to be a pretty considerable task. Besides, when he was away from the Speaker or when his absorption in the machinery removed him from that formidable influence, his thoughts took a wider cast. He was sometimes far from sure that a regeneration which began by the manufacture of heavy artillery was likely to be a process of which he could wholly approve. He found this age sufficiently agreeable not to wish to change it.

It was true that innumerable conveniences had gone. But on the other hand most of the people seemed to be reasonably contented, and no one was ever in a hurry. The Speaker, Jeremy often thought, was principally bent on regenerating those vices of which the world had managed to cure itself. The trains were few and uncertain, and, from the universal decay of mechanical knowledge, were bound in time to cease altogether; but England, so far as Jeremy could see, would get on very well without any trains at all. There was no telephone; but that was in many ways a blessing. There was no electric light, except here and there, notably, so he learnt, in some of the Cotswold towns, which were again flourishing under the rule of the wool-merchants and where it was provided by water-power to illuminate their great new houses. But it was certainly possible to regard candles and lamps as more beautiful. The streets were dark at night and not oversafe; but no man went out unarmed or alone after sunset, and actual violence was rare. Jeremy was anxious to see what the countryside looked like, when the Speaker would allow him a tour out of London. He gathered that it was richer and more prosperous than he had known it, and that the small country town had come again into its own. He learnt with joy that the wounds made by the bricks and mortar of the great manufacturing cities had, save in isolated places, in parts of Yorkshire and Wales, long been healed by the green touch of time. He formed for himself a pleasant picture of the new England, and, when his mind was his own, he shrank from disturbing it.

But when the Speaker, with mad eyes and clawing gestures, muttered beside him, he turned again with an almost equal fanaticism to the hopeless business of restoring all that was gone and that was better gone. And, under this slave-driver’s eye, he had little time for anything else. Even at night they generally dined alone together in the Speaker’s own room; and Jeremy, drugged and stupefied with fatigue, sat silent while the old man continued his unflagging monologue. And every day his enthusiasm grew greater, his demands for haste more frequent and more urgent. Only never, in all the ramblings of his speech, did he once betray the use he intended to make of the guns, the reason for his urgency.

Jeremy looked out from this existence and saw a resting world in which he alone must labor. The strain began to tell on his nerves; and he sometimes complained weakly to himself that the nightmare, into which he had awakened, endured and seemed to have established itself as a permanency. He had none save fleeting opportunities of seeing the Lady Eva. On the few occasions when they met it had been in the presence of the Lady Burney; and the girl had conducted herself with silent, almost too perfect, propriety. Jeremy, much too tired and harassed to think out anything clearly, concluded that circumstances had, once again in his life, taken the wrong turn and that his luck was out.

One morning, about three weeks after his first visit to the workshop, he succeeded for the first time in fitting the already completed breech-block into the gun and satisfied himself that the delicate mechanism, though it left much to be desired and would not last very long, would do well enough. He looked up wearily from this triumph and saw the old gnomes, his colleagues, grotesquely working all around him. Gradually, as he became convinced of the Speaker’s insanity, these uncouth creatures had grown more human and individual in his eyes and less like a chorus in one of Maeterlinck’s plays. He had not been busy all the time with that infernal screw-thread. He had looked now and then into a smaller shed close by, where in the most primitive manner and with an appalling disregard of safety, an aged workman occupied himself with the production of explosives. This man was a little more intelligent than the rest, and had studied with devotion a marvelous collection of old and rapidly disintegrating handbooks on his subject. He was a small and skinny creature, with an alert manner and a curious skipping walk; and Jeremy had got used to seeing the hatchet face bobbing towards him with demands for help.

Now, as he rested for a moment, there was a noise that penetrated even his dulled consciousness; and, as he started up in alarm, Hatchet-face skipped in, bursting with inarticulate excitement. It appeared, when he was able to speak, that he had just missed blowing off his left hand with the first detonator to function in an entirely satisfactory way; and, while one of his fellows bandaged his hurts, he continued to rejoice, showing a praiseworthy absence of self-concern. The hubbub attracted the Speaker, who was not far away; and when he arrived he learnt with delight of its cause. Jeremy capped this news with his of the breech-lock; and for a moment the old man’s terrifying countenance was lit up with a wholly human and simple happiness. Then he announced that they would not attend at the workshop that afternoon. Jeremy, from the bench on which he had laxly subsided, remarked that they deserved a holiday.

“It is not that,” said the Speaker, frowning again. “It is a reception to which I must go, an affair of ceremony, and I wish you to come with me. There will be some kind of a show.”

Jeremy was not sure what significance this variable word might by now have acquired, and he did hot much care. He looked forward to an afternoon’s relaxation. He was thankful for so much; but he wondered at the back of his mind what the Speaker would want to start on now that the guns were nearly finished.

The reception was to be held at the house of one Henry Watkins, a big man with large estates near London and in Kent, whom Jeremy had met and had a little remarked. He seemed to be the most influential and the most consulted frequenter of the Treasury; and Jeremy observed that the Speaker commonly mentioned him with rather less than his usual contempt. His house was a large one, almost exactly on the site of Charing Cross, with gardens stretching down to the river; and here, when their carriage arrived, he came out and with easy respectfulness helped the Speaker to alight.

He was a tall man, with a long, narrow face and a slightly fretful expression. As he took the old man’s arm Jeremy fancied that he whispered something, and that the Speaker shook his head. Then he turned to Jeremy and said perfunctorily, “I have had the happiness of making your acquaintance,” wheeled back to the Speaker and went on: “We waited only for you, sir. The Lady Burney and the Lady Eva and Thomas Wells are already here.”

“Then lead us to them,” the Speaker replied. And as they were being conducted through a crowd of waiting guests, who made way for them with a quiet buzz of deferential salutations, he observed in a gracious tone, “I need not ask whether you have a good show for us, Henry Watkins.”

“I trust that it will please you, sir,” the host replied. “I have heard this troop very well spoken of.”

Jeremy was prepared by this conversation for something in the way of a performance; and he was therefore not surprised when they were ushered into a large room, which had been rudely fitted up as a theater. At the front, standing by themselves, were four gilt armchairs, and on these Jeremy thought he recognized the backs of the Speaker’s wife, of his daughter, and of Thomas Wells. They caught the Speaker’s notice, too, and he halted suddenly, craning his head forward and peering at them.

“There are only four chairs,” he said in a rasping voice. “I wish another chair to be brought for my friend, Jeremy Tuft.” In a moment, after some confusion, Jeremy found himself sitting next to the Lady Eva and hearing her demure reply to his greeting, which was almost drowned by the noise of the guests behind them entering the hall. When this had died down, he essayed a second remark, but received no answer beyond an inclination of the beautiful head, which he was devoutly studying with a strained side-long glance. He therefore examined the stage instead and saw that it was already set with roughly-painted canvas flats. These appeared to be intended to represent a wood. There was no curtain; and the end of what looked remarkably like a piano was projecting from one of the wings. Tall canvas screens ran from the two ends of the stage to the walls of the room, covering on each side a space about five feet long; and Jeremy surmised, from a persistent whispering and from an occasional bulging of the canvas, that the players were hidden in these narrow quarters.

Presently three loud raps were heard and a hush fell on the audience. Jeremy started in his seat when an invisible performer at the piano began to play what sounded like a mangled waltz, very loud, very crude and very vulgar. The strings of the piano were in indifferent condition, the skill of the executant was no better, and Jeremy, who was proud of having some sympathy for music, suffered a little. When he looked about him, however, he saw neither amusement nor annoyance on any face. Luckily the performance lasted only a few minutes. As soon as it was done, an actress tripped affectedly on to the stage from the right side and began to declaim in a voice so high pitched and theatrical and with so many gestures and movements of her head that Jeremy could hardly understand a word of what she was saying. He gathered that she had come to this wood to meet her lover; and his guess was confirmed when an actor strode on from the left, stamping his feet on the resounding boards as he came. Then both began to declaim at one another in voices of enormous power. Their stilted violence alarmed and repelled Jeremy. He ceased to look at the stage, wondering whether, under cover of the excitement which this scene must be causing, he dared steal a glance at the Lady Eva. He did so, and discovered that she was looking at him.

Both averted their eyes, and Jeremy sat staring at the floor, his heart beating and, he felt certain, his cheeks burning. Above his head the drama ranted along with a loud monotonous noise like the sea beating on rocks, and made a background to his thoughts. That single glance had precipitated his emotions, and he must now confess to himself, what had been before a mere toy for the brain, that he loved this girl. The admission carried his mind whirling wildly away, and he would have been content to brood on it with a secret rising delight until he was interrupted. But he could not help asking himself whether he had not discovered something else, whether there had not been at least a particular interest in the eyes of the Lady Eva. This second thought at first terrified him by its revelation of his own audacity in conceiving it. For a moment it stopped him still, and then suddenly there was silence on the stage.

The actor and the actress were departing, she to the right, he to the left, bowing as they went. The whole audience began clapping in a decorous and gentle manner. The Lady Eva leant slightly towards Jeremy as he sat stupefied and motionless, and whispered:

“You must clap. You will be thought impolite if you do not.”

He obeyed in a dazed way, watching her and seeing how she brought the palms of her hands together, regularly but so softly that it made hardly any sound. While the applause still continued, servants came forward from the sides of the hall, sprang up on the stage and began removing the scenery, which they replaced with other flats, representing a street. And after an interval, and another performance on the vile piano, the play resumed its course.

Jeremy must have followed it with some part of his mind of the existence of which he was ignorant: for when it was all over he had a reasonably clear notion of what it had been about. There had been two lovers and a villain and a buffoon who fell over his own feet. There had been one affecting moment when the heroine, deserted and hopeless, had been deluged with small pieces of paper, not too skilfully sprinkled on her, while she walked up and down, striving to comfort her child and lamenting the perfidy of man. And the play itself, as well as the acting, had been of an incredible theatricality and exaggeration. If Jeremy’s conscious mind had been active while the performance was going on he could not but have followed every point with amazement and indulged in some interesting reflections on the dramatic tastes of his new contemporaries. As it was, when it was over and he was able to look back on it, he could only wonder whether his unaccountable recollection of it was to be believed.

For after the end of the first scene, after the Lady Eva had spoken to him, he was plunged even more deeply into that delicious but alarming turmoil of feeling. His mind unbidden suggested to him sobering considerations only for the pleasure, as it appeared, of seeing them flung on one side. There was no certainty, no probability even, that the girl had loved him. In his story there was enough reason why she should look at him with interest, and he had learnt that her usual manner was frank and unstudied, not therefore to be too easily construed. Yet a mad certainty rose in his heart and overwhelmed this sensible thought. Jeremy closed his eyes resolutely to the buffoon on the stage, who was now imitating a drunken man and abandoned himself to visions of the girl at his side.

At that moment he would perhaps have been unwilling to be awakened to speak to her, even to embrace her. That would come, must come; but this exquisite dreaming, hitherto unknown to him, filled the circle of his forces, satisfied all his desires. He pictured her as he had seen her half-a-dozen times, walking across a room, lifting her eyes to his with some question in them, once riding, once with a piece of needlework in her hands, of which, without liking it, she was making a sound and creditable job. He thought of her clear, wide eyes, her free, athletic carriage, her pleasant voice. For a little while he was in neither the strange nor the familiar world of his twofold experience: his new hope had dissolved both recent and ancient memories alike. Then suddenly across the texture of his passionate meditation came a thought of himself. He shifted uneasily and felt cold. Who and what was he? He told himself — a sport of nature, a young man unnaturally old, an old man unnaturally young. Could he be certain yet what trick it was that Trehanoc’s ray had played on him? Might he not, one day, to-morrow or a year hence, perhaps in her very arms, suddenly expire, even crumble into dust? He shuddered in the chilling air of these suggestions and was filled with misery. But the next moment he could see himself confessing his misery to the Lady Eva and receiving her comfort.

He woke. Mixed with the light clapping, in which from time to time he had mechanically joined, there was a stir and shuffle as though the audience was preparing to depart; and, looking up, he saw the whole cast on the stage, bowing with a certain air of finality, the hero and the villain holding each a hand of the heroine. The Speaker was rising from his seat, and at that sign all the other persons in the room rose, too, and waited. Jeremy, brought down out of dreams, searched in his mind for something to say to the Lady Eva and dared not look at her until he had found it. But when he turned to her he saw that she was staring in another direction. A servant had just reached the Speaker and had apparently given him a letter. The whole assembly stood hushed and immobile while he read it, and Jeremy, his breath caught by an inexplicable sense of crisis, saw that, half-way through, the old man’s hand jerked suddenly and was steady again.

The interruption, the hushed seconds that followed, seemed to spread an impalpable sense of dismay through the hall. Henry Watkins, his fretful expression deepened to one of alarm, made his way to the Speaker’s side and whispered something in an anxious voice; but the old man waved his hand impatiently and went on reading.

“What is it?” Jeremy whispered sharply to the Lady Eva.

“I don’t know… I don’t know…” she uttered; and then, so low that he could hardly catch it, “I am afraid for him…”

Jeremy stared all around in the hope that somewhere he might find some enlightenment. But there was no trace of understanding on the faces of any of the guests. The Lady Burney stood lumpishly by her husband in an attitude of annoyance and boredom. Beyond her Thomas Wells half-leant on his chair in a barbaric but graceful pose, like that of a hunting animal at rest. Jeremy fancied for a moment that he could read some sort of comprehension, some sort of satisfaction even, in those vulpine features, in the small eyes, the swelling nostrils, the thin, backward-straining mouth. And still the Speaker read on, motionless, without giving a sign, while Henry Watkins stood at his elbow as though waiting for an order; and still the Lady Eva gazed at them, crumpling restlessly with one hand a fold of her dress.

All at once the grouping broke up, and the Speaker’s voice came, steady and clear but not loud. “I must go back to the Treasury,” he said. “I am sorry I cannot stay to speak with your guests, Henry Watkins, but you must dismiss them. I wish you to come with me. And I need you, too, Jeremy Tuft; you must follow us at once. And —” he hesitated, “if you will give me the benefit of your counsel in this grave matter, Thomas Wells…” The Canadian bowed a little and grinned more thinly. Jeremy found himself in a state of confusion walking at the end of the Speaker’s party towards the door. In front of him the old man had gripped Henry Watkins firmly by the sleeve and was talking to him quietly and rapidly.

Jeremy’s passing by was the sign to the other guests that they might now leave; and as he went through the door he could feel them thronging behind him. He pressed on to keep the Speaker in sight, but slackened his pace when a hand fell lightly on his shoulder. It was Roger Vaile.

“Do you know what the matter is?” Roger asked.

Jeremy shook his head.

“Well, be careful of that Canadian. I saw him looking at you while the show was on, and he doesn’t like you.”

NEXT WEEK: “We’ve had a message from the people up north. Perhaps you could see for yourself what sort of men they are. They are very unlike any one you have ever met here — rough, fierce, quarrelsome men. They have kept some of their machinery still going up there — in some of the towns they even work in factories. They have been growing more and more unlike us for a hundred years, and now the end has come — they want to force a quarrel on us.”

RADIUM AGE SCIENCE FICTION: “Radium Age” is HILOBROW’s name for the 1904–33 era, which saw the discovery of radioactivity, the revelation that matter itself is constantly in movement — a fitting metaphor for the first decades of the 20th century, during which old scientific, religious, political, and social certainties were shattered. This era also saw the publication of genre-shattering writing by Edgar Rice Burroughs, Sax Rohmer, E.E. “Doc” Smith, Jack London, Arthur Conan Doyle, Aldous Huxley, Olaf Stapledon, Karel Čapek, H.P. Lovecraft, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Yevgeny Zamyatin, Philip Gordon Wylie, and other pioneers of post-Verne/Wells, pre-Golden Age “science fiction.” More info here.

HILOBOOKS: The mission of HiLoBooks is to serialize novels on HiLobrow; and also, as of 2012, operating as an imprint of Richard Nash’s Cursor, to reissue Radium Age science fiction in beautiful new print editions. So far, we have published Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague, Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”), Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt, H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook, Edward Shanks’s The People of the Ruins, William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land, and J.D. Beresford’s Goslings. Forthcoming: E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man, Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage, and Muriel Jaeger’s The Man with Six Senses. For more information, visit the HiLoBooks homepage.

READ: Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague, serialized between January and April 2012; Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”), serialized between March and June 2012; Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt, serialized between April and July 2012; and H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook, serialized between March and August 2012.

ORIGINAL FICTION: HILOBROW has serialized three novels: James Parker’s The Ballad of Cocky The Fox (“a proof-of-concept that serialization can work on the Internet” — The Atlantic) and Karinne Keithley Syers’s Linda Linda Linda. We also publish original stories and comics.