The People of the Ruins (5)

By:

June 21, 2012

HILOBROW is pleased to present the fifth installment of our serialization of Edward Shanks’ The People of the Ruins: A Story of the English Revolution and After. New installments will appear each Thursday for 16 weeks.

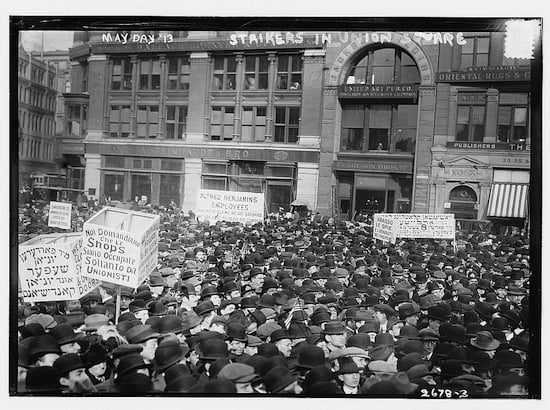

Trapped in a London laboratory during a worker uprising in 1924, ex-artillery officer and physics instructor Jeremy Tuft awakens 150 years later — in a neo-medieval society whose inhabitants have forgotten how to build or operate machinery. Not only have his fellow Londoners forgotten most of what humankind used to know, before civilization collapsed, but they don’t particularly care to re-learn any of it. Though he is at first disconcerted by the failure of his own era’s smug doctrine of Progress, Tuft eventually decides that post-civilized life is simpler, more peaceful. That is, until northern English and Welsh tribes threaten London — at which point he sets about reinventing weapons of mass destruction.

Shanks’ post-apocalyptic novel, a pessimistic satire on Wellsian techno-utopian novels, was first published in 1920. In October, HiLoBooks will publish a beautiful new edition of The People of the Ruins, with an introduction by Tom Hodgkinson.

SUBSCRIBE to HILOBROW’s serialized fiction via RSS.

LAST WEEK: “‘Men used to cross to America in less than a week. Yes — and some even flew over in aeroplanes in a day.’ ‘Uncle, uncle,” Roger remonstrated gently, “you mustn’t tell fairy tales to a man who has been to fairyland. He knows what the truth is.'”

ALL EXCERPTS: 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 |15 |16

THE SPEAKER

When Jeremy woke, the same panic terror of that transition seized him again for a moment and poised him on a razor’s edge between consciousness and unconsciousness. It passed. The clear morning light falling on his bed revealed to him that his humdrum existence in the new world began with that day. The surprises and the anxieties were over. All that remained was a process of adaptation and settlement; and, feeling a certain eagerness to begin, he began by scrambling out of bed.

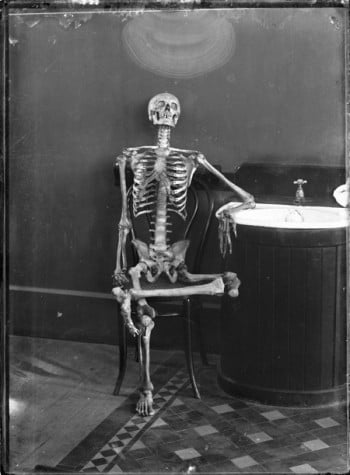

There was, as he might have remembered, no bath in the room; and he decided that to search for one along these unknown corridors would be an enterprise not less chimerical than embarrassing. He looked about the room rather helplessly and lit at last on what he had not seen the night before, a metal ewer of water with a basin, standing behind the wooden chest. There was no soap with them, and the chest turned out to be locked. He was still revolving this problem in his mind, while the nightshirt napped pleasantly round his legs in a light draught, when Roger came in, looking as placid and collected as he had been when he had shown Jeremy to bed.

“Are you well?” Roger asked; and, without waiting for a reply, he went on smoothly, “Of course you have nothing of your own for dressing. I’ve brought you my soap and a razor and a glass — and…” He hesitated a little.

“Yes?” Jeremy encouraged him.

“I thought perhaps it might be better if I were to lend you some of my clothes. You know, your own do look… If you don’t mind…”

“Of course not,” Jeremy assented with pleasure. It was the last of his desires to be in any way conspicuous. “I should very much prefer it.”

When Roger had gone he examined with some interest the soap which had been given to him. It was a thin and wasted cake, very heavy, and of a harsh and gritty substance. But what was chiefly interesting was that it lay in a little metal casket which had a lock on it. This simple fact led Jeremy’s mind down a widening avenue of speculation. He dragged himself away from it with difficulty, and was in the middle of washing and shaving when Roger returned. It was at least a relief to find that the razor had a practicable edge.

Roger sat on the bed and watched Jeremy in silence. There was nothing specially perplexing in these new clothes, which comprised a thick woolen vest, a shirt, breeches, and a loose coat, and were obviously the garments of a race, or a class, used to a life spent largely out of doors. Jeremy put them on without difficulty until he came to the shapeless bunch of colored linen which served as a tie. Here Roger was obliged to intervene and help him.

“How absurd!” Roger exclaimed with satisfaction, standing away and regarding him when the operation was completed. “Now you look like anybody else. And yet yesterday, when I found you, you looked like some one out of one of the old pictures. It’s almost a pity…”

“That’s all right,” Jeremy sighed, still fidgeting a little with the tie and trying to see himself in a very small shaving-glass. “I want to look like anybody else. It’s a great piece of luck that only you and your uncle know that I’m not. I feel somehow,” he went on, with an increasing warmth of expression, “that I can rely on you. It would be unbearable if all these people here knew what I had told you.” He paused, while the vision thus suggested took definite shape in his mind.

“You see,” he ruminated, lost in speculation and half-forgetting his hearer, “I know that nothing would ever make me believe such a story. I know they would look at me out of the corners of their eyes and wonder whether there was anything in it. They’d begin to take sides and quarrel. The fools would believe me and the sensible people would laugh at me. I should begin to feel that I was an impostor, a sort of De Rougemont or Doctor Cook… only, of course, you don’t know who they were —” He might have rambled on much longer without realizing that there was a certain ungracious candor in these remarks if his interest had not been attracted by a change of expression, a mere flicker of meaning in Roger’s eyes.

“You haven’t told any one?” Jeremy cried with a sudden gust of entreaty.

“No — well… no one of importance…” Roger answered, averting his glance. “But I didn’t know — you didn’t say — And there’s my uncle —” He paused and considered.

“But —” Jeremy began, and stopped appalled.

The pressure of experience had taught him that it was not only an error but also gross ill-behavior to make large claims of any sort whatsoever. He strongly resented finding himself in the position of having to assert in public that he had lain in a trance for a century and a half. Surely Roger should have understood his feelings without warning, and should have respected his story as told in confidence under an obvious necessity. There flashed through his mind the question whether any newspapers still survived.

He burst out again wildly, fighting with a thickness in his throat. “Will your uncle have told any one? Isn’t it much better to say nothing about me? At least, until I can prove —”

“But what do you mean — prove?” Roger interrupted. “Why shouldn’t every one believe you as I did? There are some men who will believe nothing, but —” He shrugged his shoulders and dismissed them. “But, whatever you may wish, there’s my uncle… He rises very early —I saw him here half-an-hour ago, after Mass.”

Jeremy opened his mouth to speak and forebore.

“Consider, my dear friend,” Roger went on persuasively, “we didn’t know your wishes, and it’s late in the day already. I’ve been up for some time; I’ve even begun my work. I didn’t want to wake you, because —”

“Do you mean that you’ve been talking to every one about me?” Jeremy demanded, almost hysterically.

“You speak as though you had done something that you were ashamed of. I cannot think why you should want to hide so wonderful a matter.”

Jeremy sat down on the wooden chest, unable to speak, but murmuring sullen protests in his throat. The face of the future had somehow changed since he had finished dressing; and he found himself unable to explain to Roger how important it was that his secret should be preserved, that he should slip into the strange world and lose himself with as little fuss as a raindrop disappearing in the sea. Besides, this young man was in a sort his savior and protector, to whom he owed gratitude, and on whom he certainly was dependent…. The anger which was roused in him by the placidly enquiring face opposite died away in a fit of hopelessness.

“What will happen to me then?” he muttered at last.

“You will be made much of,” Roger assured him. “Crowds will flock round you to hear your story. The Speaker and all the great men of the country will wish to see you. Now come with me and eat something. Perhaps no one knows anything about you yet, I said nothing clear. You must come and eat.”

“I don’t want to eat,” Jeremy mumbled, suffering from an intense consciousness of childish folly.

Perhaps Roger divined his feelings, for a slow, faint smile appeared on his face. “You must eat,” he repeated firmly. “You are overwrought. Come with me.” There was something in his serene but determined patience which drew Jeremy reluctantly after him.

The emptiness of the corridor outside did not reduce Jeremy’s fears of the peopled house beyond. He dragged along a pace behind Roger, trying vainly to overcome the unwillingness in his limbs. When, as they turned a corner, a servant passed them, his heart jerked suddenly and he almost stopped. But there might have been nothing in the glance which the man threw at them. They went on. Presently they turned another corner and came to a broad staircase of shallow steps made of slippery polished wood.

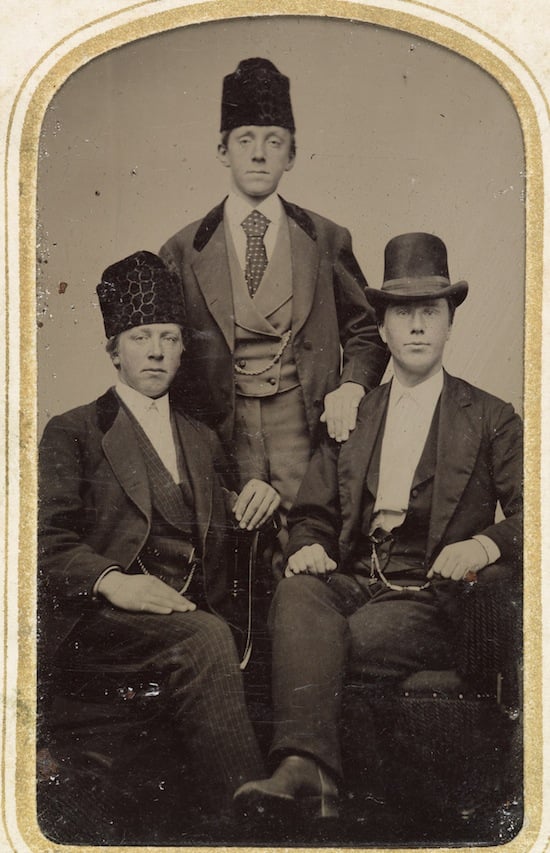

When Jeremy was on the third step he saw below a group of young men, dressed like Roger and himself, engaged in desultory morning conversation. Again he almost stopped; but Roger held on, and the group below did not look up. Their voices floated lightly to him and he recognized that they were talking to pass the time. He steeled himself for self-possession and cast his eyes downward, because his footing on the polished wood was insecure.

Suddenly his ear was struck by a hush. He lifted his eyes and looked down at the young men and saw with terror that the conversation had ceased, that their faces were turned upwards, gazing at him. He returned the stare stonily, straining his eyes so that the eager features were confused and ran into a blur. The stairs became more slippery, his limbs less controllable. Only some strange inhibition prevented him from putting out a hand to Roger for support. But Roger, still a step in front, his back self-consciously stiffened, did not see the discomfort of his charge. Somehow Jeremy finished the descent and passed the silent group without a gesture that betrayed his agitation. He fancied that one of the young men raised his eyebrows with a look at Roger, and that Roger answered him with a faint inclination of the head.

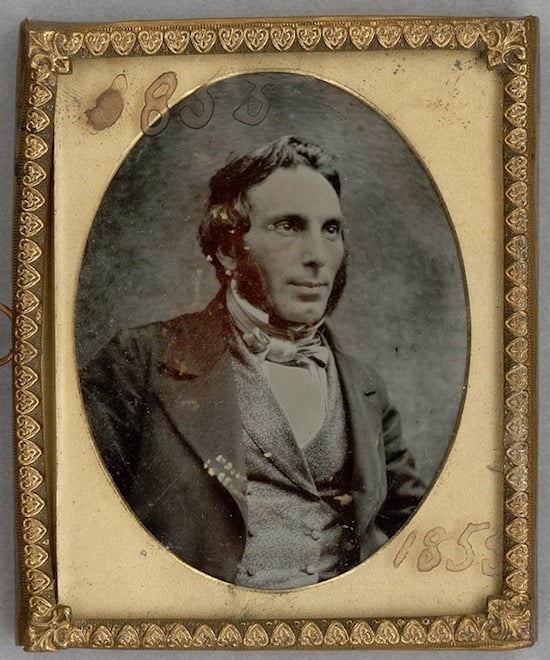

They were now in the wide passage which led to the dining-hall, and had almost reached the hall-door, when a figure which seemed vaguely familiar came into sight from the opposite direction. It was a man whose firm steps and long, raking stride, out of proportion to his moderate stature, gave him an ineffable air of confidence, of arrogance and superiority. He was staring at the ground as he walked; but when he came nearer, Jeremy was able to recognize in the lean, sharp-boned face, with the tight mouth and narrow nose, the distinguished person to whom Roger had alluded on the previous night as “that damned Canadian.” He was almost level with them when he raised his head, stared keenly at Jeremy, turned his eyes to Roger, looked back again… Then with a movement almost like that of a frightened horse and with an expression of horror and dislike, he swerved abruptly to one side, crossed himself vehemently and went on at a greater pace.

Jeremy’s sick surmise at the meaning of this portent was confirmed by Roger’s scowl and exclamation of annoyance. Both involuntarily hesitated instead of going through the open door of the hall. At the tables inside four or five men were seated, making a late but copious meal. As Roger and Jeremy halted, a servant, dressed in a strange and splendid livery, came up behind them and touched Roger lightly on the shoulder. The young man turned round with an exaggeratedly petulant movement; and the servant, looking sideways at Jeremy, began to whisper in his ear. Jeremy, his sense of apprehension deepened, drew off a pace. He could see, as he stood there waiting, two other men, dressed in what seemed much more like a uniform than a livery, half concealed in the shadow of the further corridor.

The servant’s whispering went on, a long, confused, rising and falling jumble of sound. Roger answered in a sharp staccato accent, most unlike the ordinary tranquillity of his voice, but still beneath his breath. Jeremy, with the stares of the breakfasting men on his shrinking back, felt that the situation was growing unbearable. Suddenly Roger raised and let fall his hands in a gesture of resigned annoyance.

“Then will you, sir…” the servant insisted with a deference that was plainly no more than formal.

Roger turned with unconcealed reluctance to Jeremy. “I am sorry,” he said in the defensive and sullen tone of a man who expects reproach. “The Speaker has heard of you and has sent for you. I have asked that I may go with you, but I am not allowed. You must go with this man. I… am sorry…”

Jeremy faced the servant with rigid features, but with fear playing in his eyes. The man’s back bent, however, in a bow and his expression betrayed a quite unfeigned respect and wonder.

“If you will come with me, sir,” he murmured. Jeremy repeated Roger’s gesture, and advanced a step into the darkness of the passage at the side of his conductor. He felt, rather than saw or heard, the two men in the shadow fall in behind him.

The way by which the servant led Jeremy grew darker and darker until he began to believe that he was being conducted into the recesses of a huge and gloomy castle. He had once or twice visited the Treasury, where one of his friends had been employed — nearly two hundred years ago!— on some minute section of the country’s business. He could not, however, recognize the corridors through which they passed; and he supposed that the inside of the building had been wholly remodeled. All sensation of fear left him as he walked after his guide. His case was, at all events, to be settled now, and the matter was out of his hands. He felt a complete unconcern when they halted outside a massive door on which the servant rapped sharply three times. There was a pause; and then the servant, apparently hearing some response which was inaudible to Jeremy, threw open the door, held it, and respectfully motioned him in.

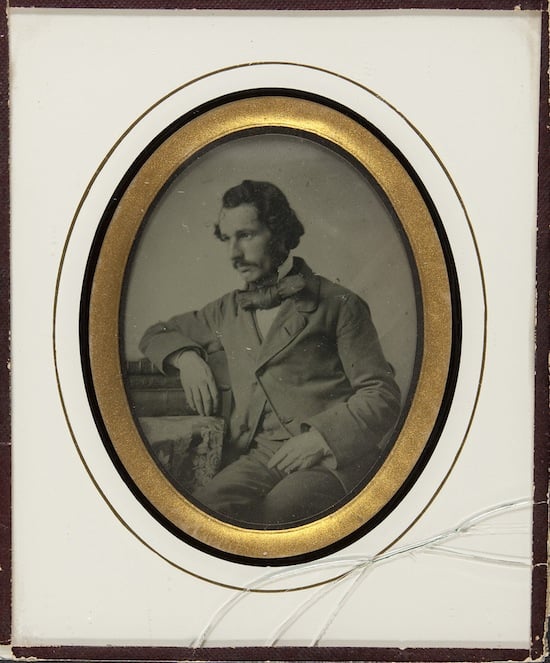

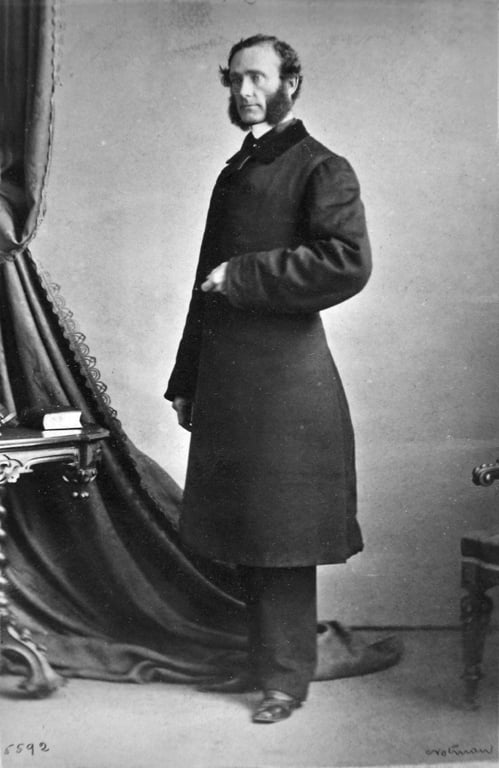

Jeremy was startled for a moment, after the darkness of the passages, to find himself in a full blaze of morning light. While he blinked awkwardly, the door closed behind him; and it was a minute or two. before he could clearly distinguish the person with whom he had been left alone. At last he became aware of a great, high-backed armchair of unpolished wood, which was placed near to the window and held the old man whom he had seen from a distance, indistinctly, the night before at dinner. This figure wore a dark robe of some thick cloth, which was drawn in loosely by a cord girdle at the waist and resembled a dressing-gown. His thick, wrinkled neck rising out of the many-folded collar supported a square, heavy head, which by its shape proclaimed power, as the face by every line proclaimed both power and age. The nose was large, hooked and fleshy, the lips thick but firm, the beard long and white; and under the heavy, raised lids the brown eyes were almost youthful, and shone with a surprising look of energy and domination. Jeremy stared without moving; and, as his eyes met those of the old man, a queer sensation invaded his spirit. He felt that here, in the owner of these eyes, this unmistakably Jewish countenance, this inert and bulky form, he had discovered a mind like his own, a mind with which he could exchange ideas, as he could never hope to do with Roger Vaile or Father Henry Dean.

The silence continued for a full minute after Jeremy had got back the use of his sight. At last the old man said in a thick, soft voice:

“Are you the young man of whom they tell me this peculiar story?” And before Jeremy could reply, he added: “Come over here and let me look at you.”

Jeremy advanced, as if in a dream, and stood by the arm of the chair. The Speaker rose with one slow but powerful movement, took him by the shoulder and drew him close against the window. He was nearly a head taller than Jeremy, but he bent only his neck, not his shoulders, to stare keenly into the younger man’s face. A feeling of hope and contentment rose in Jeremy’s heart; and he endured this inspection for several moments in silence and with a steady countenance. At last the old man let his hand fall, turned away and breathed, more inwardly, almost wistfully: “If only it were true!”

“It is true,” Jeremy said. There was neither expostulation nor argument in his voice.

The Speaker wheeled round on him with a movement astonishingly swift for his years and his bulk. “You will find me harder to persuade than the others,” he said warningly.

“I know.” And Jeremy bore the gaze of frowning enquiry with a curiously confident smile.

The Speaker’s reply was uttered in a much gentler tone. “Come and sit down by me,” he murmured, “and tell me your story.”

Jeremy took a deep breath and began. He told his story in much more detail than he had given to Roger, dwelling on the riots and their causes, and on Trehanoc’s experiment and his own interpretation of its effect. He did not spare particulars, both of the strikes, as well as he remembered them, and of the course of scientific investigation which had landed him in this position; and as he proceeded he warmed to the tale, and gave it as he would have done to a man of his own sort in his own time. The brown eyes continued to regard him with an unflickering expression of interest. When he paused and looked for some comment, some sign of belief or, disbelief, the thick voice murmured only:

“I understand. Go on.”

Jeremy described his awakening, the terrors and doubts that had succeeded it and his eventual dismay when he was able at last to climb into the world again. He explained how he had gone back with Roger to the crevice, how they had seen the rat run out, and how he had found the vacuum-tube. When he had finished, the Speaker was silent for a moment or two. Then he rose and walked slowly to a desk, which stood in the further corner of the room. He returned with an ivory tablet and a pencil which he gave into Jeremy’s hands.

“Mark on that,” he said, “the River Thames and the position of as many of the great railway stations of London as you can remember.”

Jeremy suffered a momentary bewilderment, and stared at the intent but expressionless face of the old man, with an exclamation on his lips. But instantly he understood, and, as he did so, the map of old London rose clearly before his eyes. He drew the line of the river and contrived to mark, with reasonable accuracy, on each side of it as many of the stations as he could think of. He forgot London Bridge; and he explained that there had been a station called Cannon Street, which he had, for some reason, never had occasion to use, and that he did not know quite where it had stood.

The Speaker nodded inscrutably, took back the tablet and studied it. “Do you remember London Bridge!” he asked. Jeremy bit his lip and owned that he did. “Then can you say,” the Speaker went on, “whether it was north of the river or south?”

Jeremy discovered, with a wild anger at his own idiocy, that he could not remember. It would be absurd, horribly absurd, if his credit were to be at the mercy of so unaccountable a freak of the brain. He thought at random, until suddenly there appeared before his mind a picture of the bridge, covered with ant-like crowds of people, walking in the early morning from the station beyond.

“It was on the south,” he cried eagerly. “I remember because —”

The Speaker held up a wrinkled but steady hand. “Your story is true,” he said slowly. “I know very well, as you know, that nothing can prove it to be true; but nevertheless I believe it. Do you know why I believe it?”

“I think so,” Jeremy began with hesitation. He felt that keen gaze closely upon him.

“It would be strange if you knew in any other way what only three or four men in the whole country have cared to learn. You could have learnt it, no doubt, from maps, or books. Such exist, though none now look at them. Yet how should you have guessed what question I would ask you? Do you know that of those stations only two remain? I know where the rest were, because I have studied the railways, wishing to restore them. But now they are all gone and most of them even before my time. They were soon gone and forgotten. When I was a boy I walked among the ruins of Victoria, just before it was cleared by my grandfather to extend his gardens. Did you go there ever when the trains were running in and out?”

The question aroused in Jeremy vivid memories of departures for holidays in Sussex, of the return to France after leave…. He replied haltingly, at random, troubled by recollections.

The same trouble was in the old man’s eyes as he listened. “It is true,” he said, under his breath, almost to himself. “You are an older man than I am.” A long pause followed. Jeremy was the first to return from abstraction, and he was able, while the Speaker mused, to study that aged, powerful face, to read again a determination in the eyes and jaw, that might have been fanaticism had it not been corrected by the evidence of long and subduing experience in the lines round the mouth and eyes.

At last the Speaker broke the silence. “And in that life,” he said, “you were a scientist?” He pronounced the word with a sort of lingering reverence, as though it had meant, perhaps, magician or oracle.

Jeremy tried to explain what his learning was, and what his position had been.

“But do you know how to make things?”

“I know how to make some things,” Jeremy replied cautiously. Indeed, during the social disorders of his earlier existence he had considered whether there was not any useful trade to which he might turn his hand, and he had decided that he might without difficulty qualify as a plumber. The art of fixing washers on taps was no mystery to him; and he judged that in a week or two he might learn how to wipe a joint.

The Speaker regarded him with a growing interest, tempered by a caution like his own. It seemed as though it took him some time to decide upon his next remark. At last he said in a low and careful voice:

“Do you know anything about guns?”

Jeremy started and answered loudly and cheerfully: “Guns? Why, I was in the artillery!”

The effect of this reply on the Speaker was remarkable. For a moment it straightened his back, smoothed the wrinkles from his face, and threw an even more vivid light into his eyes. When he spoke again, he had recovered his self-possession.

“You were in the artillery?” he asked. “Do you mean in the great war against the Germans?”

“Yes — the great war that was over just before the Troubles began.”

“Of course… of course… I had not realized —” It seemed to Jeremy that, though the old man had regained control of himself, this discovery had filled him with an inexplicable vivacity and excitement. He pressed Jeremy eagerly for an account of his military experience. When the simple tale was done, he said impressively:

“If you wish me to be your friend, say not one word of this to any man you meet. Do you understand? There is to be no talk of guns. If you disobey me, I can have you put in a madhouse.”

Jeremy lifted his head in momentary anger at the threat. But there was an earnestness of feeling in the old man’s face which silenced him. This, he still queerly felt, was his like, his brother, marooned with him in a strange age. He could not understand, but instinctively he acquiesced. “I promise,” he said.

“I will tell you more another day,” the Speaker assured him. And then, with an abrupt transition, he went on, “Do you understand these times?”

“Father Henry Dean —” Jeremy began.

“Ah, that old man!” the Speaker cried impatiently. “He lives in the past. And was it not his nephew, Roger Vaile, that brought you here?” Jeremy made a gesture of assent. “Like all his kind, he lives in the present. What must they not have told you between them? Understand, young man, that you are my man, that you must listen to none, take advice from none, obey none but me!” He had risen from his chair and was parading his great body about the room, as though he had been galvanized by excitement into an unnatural youth. His soft, thick voice had become hoarse and raucous: his heavy eyelids seemed lightened and transfigured by the blazing of his eyes.

Jeremy, straight from a century in which display of the passions was deprecated, shrank from this exhibition while he sought to understand it.

“If I can help you —” he murmured feebly.

“You can help me,” the Speaker said, “but you shall learn how another day. You shall understand how it is that you seem to have been sent by Heaven just at this moment. But now, tell me what do you think of these times?”

“I don’t know,” Jeremy began uncertainly. “I know so little. You seem to have lost almost all that we had gained —”

“And yet?” the Speaker interrupted harshly.

Jeremy sought to order in his mind the confused and contradictory thoughts. “And yet perhaps you have lost much that is better gone. This world seems to me simpler, more peaceful, safer… We used to feel that we were living on the edge of a precipice — every man by himself, and all men together, lived in anxiety….”

“And you think that now we are happy?” the old man asked with a certain irony, pausing close to Jeremy’s chair, so that he towered over him. “Perhaps you are right — perhaps you are right…. But if we are it is the happiness of a race of fools. We, too, are living on the edge of a precipice as terrible as any you ever knew. Do you believe that any people can come down one step from the apex and fall no further?” He contemplated Jeremy with eyes suddenly grown cold and calculating. “You were not, I think, one of the great men, one of the rulers of your time. You were one of the little people.” He turned away and resumed his agitated pacing up and down, speaking as though to himself. “And yet what does it matter? The smallest creature of those days might be a great man to-day.”

A profound and dreadful silence fell upon the room. Jeremy, feeling himself plunged again in a nightmare, straightened himself in his chair and waited events. The Speaker struggled with his agitation, striding up and down the room. Gradually his step grew more tranquil and his gestures less violent; his eyes ceased to blaze, the lids drooped over them, the lines round his mouth softened and lost their look of cruel purpose.

“I am an old man,” he murmured indistinctly. His voice was again thick and soft, the voice of an elderly Jew, begging for help but determined, even in extremity, not to betray himself. “I am an old man and I have no son. These people, the people of my time, do not understand me. When my father died, I promised myself that I would raise this country again to what it was, but year after year they have defeated me with their carelessness, their indolence… If you can help me, if you understand guns… if you can help me, I shall be grateful, I shall not forget you.”

Jeremy, perplexed almost out of his wits, muttered an inarticulate reply.

“You must be my guest and my companion,” the Speaker went on. “I will give orders for a room near my own apartments to be prepared for you, and you shall eat at my table. And you must learn. You must listen, listen, listen always and never speak. I will teach you myself; but you must learn from every man that comes near you. Can you keep your tongue still?”

“I suppose so,” said Jeremy, a little wearily. He was beginning to think that this old man was possibly mad and certainly as incomprehensible as the rest. He was oppressed by these hints and mysteries and enigmatic injunctions. He thought that the Speaker was absurdly, unreasonably, melodramatically, making a scene.

A change of expression flickered over the Speaker’s face. “I have no son,” he breathed, as though to himself, but with eyes, in which there was a look of cunning, fixed on Jeremy. And then he said aloud, “Well, then, you are my friend and you shall be well treated here. Now you must come with me and I will present you to my wife… and… my daughter.”

In the sensations of that morning the last thing that troubled Jeremy was to find himself carrying on a familiar conversation with a prince. He accepted it as natural that his accident should have made him important; and he conducted himself without discomfort in an interview which might otherwise have embarrassed and puzzled him — for he was self-conscious and awkward in the presence of those who might expect deference from him. He was first recalled to the strangeness of the position by the Speaker’s eager informality.

It was true that he was unacquainted with the habits of courts in any century. And yet should not the Speaker have called a servant or perhaps even a high official, instead of thus laying his own hand on the door and beckoning his guest to follow? Jeremy failed for a moment to obey the gesture, standing legs apart, considering with a frown the old man before him. It was nothing but an elderly Jew, by turns arrogant and supplicating, moved perhaps a little over the edge of sanity by his great age and by disappointed ambitions.

Then he started, recovered his wits and followed the crooked finger. They went out into the passage together. As they came into the gloom the old man suddenly put his arm round Jeremy’s shoulders and, stooping a little to his ear, murmured in a manner and with an accent more than ever plainly of the East:

“My son, my son, be my friend and I will be yours. And you must be a little respectful to the Lady Burney, my wife. She will think it strange that I bring you to her without ceremony. She is younger than I am, and different from me, different from you. She is like the rest. But I do nothing without reason…”

Jeremy stiffened involuntarily under the almost fawning caress and muttered what he supposed to be a sufficient answer. The old man withdrew his arm and straightened his bent back; and they continued their way together in silence.

Presently they came into a broader and lighter corridor, the windows of which opened on to a garden. Jeremy recognized it as the garden he had seen from his room the evening before, and, looking aside as they passed, he caught a glimpse of a party of young men, busy at some game with balls and mallets — a kind of croquet, he imagined. They went on a few paces, and a servant, springing up from a chair in a niche, stood in a respectful attitude until they had gone by. At last the Speaker led the way into a small room where a girl sat at a table, languidly playing with a piece of needlework.

She, too, sprang to her feet when she saw who it was that had entered; and Jeremy looked at her keenly. This was the first woman he had seen at close quarters since his awakening, and he was curious to find he hardly knew what change or difference. She was short and slender and apparently very young. Her dress was simple in line, a straight garment which left the neck bare, but came up close to it and fell thence directly to her heels, hardly gathered in at all by a belt at the waist. Its gray linen was covered from the collar to the belt by an intricate and rather displeasing design of embroidery, while broad bands of the same pattern continued downward to the hem of the long skirt. Her hair was plaited and coiled, tightly and severely, round her head. Her attitude was one of submission, almost of humility, with eyes ostentatiously cast down; but Jeremy fancied that he could see a trace of slyness at the corners of her mouth.

“Is your mistress up, my child?” the Speaker asked In a tone of indifferent benevolence.

“I believe so, sir,” the girl answered.

“Then tell her that I wish to present to her the stranger of whom she has heard.”

She bowed and turned, not replying, to a further door; but as she turned she raised her eyes and fixed them on Jeremy with a frank, almost insolent stare. Then, without pausing, she was gone. The Speaker slipped into the chair she had left and drummed absently with his fingers on the table. When the girl returned he paid hardly any attention to her message that the Lady Burney was ready to receive them. A fit of abstraction seemed to have settled down on him; and he impatiently waved her on one side, while he drew Jeremy in his train.

Jeremy was doubtful how he ought to show his respect to the stout and ugly woman who sat on her couch in this room with an air of bovine dissatisfaction. He bowed very low and did not, apparently, increase her displeasure. She held out two fingers to him, a perplexing action; but it seemed from the stiffness of her arm that she did not expect him to kiss them. He shook and dropped them awkwardly and breathed a sigh of relief. Then he was able to examine the first lady of England and her surroundings, while, with much less interest and an expression of stupid aloofness, she examined him.

She was dressed in the same manner as the girl who waited in the ante-room, though her gown seemed to be of silk, and was much more richly as well as more garishly embroidered. It struck Jeremy that she harmonized well with the room in which she sat. It was filled with ornaments, cushions, mats and woven hangings of a coarse and gaudy vulgarity; and the woodwork on the walls was carved and gilded in the style of a florid picture-frame. The occupant of this tawdry magnificence was stout, and her unwieldy figure was disagreeably displayed by what seemed to be the prevailing fashion of dress. Her cheeks were at once puffy and lined and were too brilliantly painted; and the lashes of her dull, heavy eyes were extravagantly blackened. Jeremy hoped that his attitude, while he noted all these details, was sufficiently respectful.

It must have satisfied the Lady Burney, for, after a long pause, she observed in a gracious manner:

“I was anxious to see you. Why do you look like everyone else? I thought your clothes would have been different.”

Jeremy explained that he had been clothed anew so that he should not appear too conspicuous. She assented with a movement of her head and went on:

“It would have been more interesting to see you in your old clothes. Do you — do you —” She yawned widely and gazed round the room with vague eyes, as though looking for the rest of her question. “Do you find us much changed?” she finished at last.

“Very much changed, madam,” Jeremy replied with, gravity. “So much changed that I should hardly know how to begin to tell you what the changes are.”

She inclined her head again, as though to indicate that her thirst for knowledge was satisfied. At this point the Speaker, who had been standing behind Jeremy, silent but tapping his foot on the ground, broke in abruptly.

“Where is Eva?” he said.

The lady looked at him with a corpulent parody of reserve. “She has just come in from riding. Shall I send for her?” The Speaker nodded, and then seemed to wave away a question in her eyes. She turned to Jeremy and murmured, “The bell is over there.”

Jeremy stared at her a moment, puzzled; then, following the direction of her finger, saw hanging on the wall an old-fashioned bell-pull. Recovering himself a little he went to it, tugged at it gingerly, and so summoned the girl who sat in the ante-room. When she came in he saw again on her face the same look of frank but unimpressed curiosity. But she received her orders still with downcast and submissive eyes and departed in silence.

Then a door at the other end of the room opened abruptly and gustily inwards. Jeremy looked towards it with interest, saw nothing but a hand still holding it, and, dimly, a figure in the opening turned away from it. He heard a fresh, cheerful voice giving some parting directions to an invisible person. The blood rose suddenly to his head and he began to be confused. He waited in almost an agony of suspense for the Speaker’s daughter to turn and enter the room.

He had indeed experienced disturbing premonitions of this sort before. Now and again it had happened in the life of his own lecture-rooms and of his friends’ studios, that, without reason, he wondered why he had been so immune from serious love-sickness. Now and again, like a child with a penny to spend, he would take his bachelor state out of some pocket in his thoughts, turn it over lovingly, and ask himself what he should do with it. He had indeed a great fear of spending it rashly; but often, after one of these moods, the mention of an unknown girl he was to meet would set his heart throbbing, or he would look at one of his pupils or one of his friends with a new and faintly pleasant speculation in his mind. Yet there had never been anything in it. He had had one flirtation over test-tubes and balances, ended by his timely discovery of the girl’s pretentious ignorance in the matter of physics. He would not have minded her being ignorant, but he was repelled when he thought that she had baited a trap for him with a show of knowledge. There had been another over canvases and brushes. But he had not been able to talk with enough warmth about the fashions of art; and, before he had made much progress, the girl had found another lover more glib than he — which was, he reflected, when he was better of his infatuation and considered the kind of picture she painted, something of a deliverance. Now his heart was absurdly beating at the approach of a princess — of a princess who was nearly two hundred years younger than himself!

She turned and came into the room, stopping a few paces inside and staring at him as frankly as he at her. She must have seen in him at that moment what we see in the house where a great man was born — a house that would be precisely like other houses if we knew nothing about it. Or did her defeated curiosity wake in her even then extraordinary thoughts about this ordinary young man? Jeremy’s mind had become too much a stage set for a great event for him to get any clear view of the reality. But he received an impression, ridiculously, as though the fine, blowing, temperate, sunshiny day he had seen through the windows had come suddenly into his presence. And, though this tall, straight-backed girl, with her wide, frank eyes and all the beauty of health and youth, had plainly her mother’s features, distinguished only by a long difference of years, he guessed somehow in her expression, in her pose, something of the father’s intelligence.

The pause in which they had regarded one another lasted hardly ten seconds. “I wanted so much to see you,” she cried impulsively. “My maids have told me all about you, and when I was out riding —” She stopped.

The Lady Burney frowned, and the Speaker asked in a slow, dragging voice, as though constraining himself to be gentle, “Whom did you meet when you were out riding?”

“Roger Vaile,” the girl answered, with a faint tone of annoyed defiance. “And he told me how he came to find this gentleman yesterday.”

“I am very much in his debt,” Jeremy said. “I suppose he saved my life.”

“You should not be too grateful to him,” the Speaker interposed, in a manner almost too suave. “Any man that found you must have done what he did. You are not to exaggerate your debt to him.”

The girl laughed, and suppressed her laughter, and again the Lady Burney frowned. Jeremy, scenting the approach of a family quarrel and unwilling to witness it, spoke quickly and at random in the hope of relieving the situation: “I hope, sir, you will allow me to be grateful to Mr. Vaile, who was, after all, my preserver, and treated me kindly.”

The girl laughed again, but with a different intention. “Mister?” she repeated. “What does that mean?”

Jeremy looked at her, puzzled. “Don’t you call people Mister now?” He addressed himself directly to her and abandoned his attempt to embrace in the conversation the Speaker, who was trying to conceal some mysteriously caused impatience, and the Lady Burney, who was not trying at all to conceal her petulant but flaccid displeasure.

“No,” said the girl, equally ignoring them. “We call Roger Vaile so because he is a gentleman. If he were a common man we should simply call him Vaile. Did you call gentlemen — what was it?—Mister, in your time?” Jeremy, studying her, admiring the poise with which she stood and noting that, though she wore the narrow, simply-cut gown of the rest, it was less tortured with embroidery, strove to find some way of carrying on the conversation and suddenly became aware that there was some silent but acute difference between the Speaker and his wife.

“Eva!” the Lady Burney broke in, disregarding her husband’s hand half raised in warning. “Eva,” she repeated with an air of corpulent and feeble stateliness, “I am fed up with your behavior!”

Jeremy started at the phrase as much as if the stupid, dignified woman had suddenly thrown a double somersault before him. But he could see no surprise on the faces of the others, only unconcealed annoyance and alarm.

“You may go, Eva,” the Speaker interposed with evident restraint. “Jeremy Tuft is to be our guest, and you will see him again. He has much to learn, and you must help us to teach him.”

The girl, as though some hidden circumstance had been brought into play, instantly composed her face and bowed deeply and ceremoniously to Jeremy. He returned the bow as well as he was able, and had hardly straightened himself again before she had left the room.

“I am fed up with our daughter’s behavior,” the Lady Burney repeated, rising. “I will go now and speak to her alone.” Then she too vanished, ignoring alike her husband’s half-begun remonstrance and Jeremy’s second bow.

It was with some amazement that Jeremy found himself alone again with the old man. His brain staggered under a multitude of impressions. The astonishing locution employed by the great lady had been hardly respectable in his own day, and it led him to consider the strange, pleasant accent which had struck him in Roger Vaile’s first speech and which was so general that already his ear accepted it as unremarkable. Was it, could it be, an amazing sublimation of the West Essex accent, which in an earlier time had been known as Cockney? Then his eye fell on the silent, now drooping figure of the Speaker, and recalled him to the odd under-currents of the family scene he had just beheld.

“My wife comes from the west,” said the Speaker in a quiet, tired voice, catching his glance, “and sometimes she uses old-fashioned expressions that maybe you would not understand… or perhaps they are familiar to you…. But tell me, how would a father of your time have punished Eva for her behavior?”

“I don’t know,” Jeremy answered uncomfortably. “I don’t know what she did that was wrong.”

The Speaker smiled a little sadly. “Like me, she is… is unusual. She should not have addressed you first or taken the lead so much in speaking to you. I fear any other parent would have her whipped. But I—” his voice grew a little louder, “but I have allowed her to be brought up differently. She can read and write. She is different from the rest, like me… and like you. I have studied to let her be so… though she hardly thinks it… and I daresay I have not done all I should. I have been busy with other things and between the old and the young… I was already old when she was born — but now you…” His voice trailed away into silence, and he considered Jeremy with full, expressionless eyes. At last he said, “Come with me and I will make arrangements for your reception here. In a few days I shall have something to show you and I shall ask your help.” Jeremy followed, his mind still busy. His absurd premonitions had been driven away by tangled speculations on all these changes in manners and language.

NEXT WEEK: “Jeremy was astonished to find alternately how much and how little he remembered of London, how much and how little had survived. Westminster Bridge, looking old and shaky, still stood; but the Embankment was getting to be disused, chiefly on account of a great breach in it, how caused Roger could not tell him, in the neighborhood of Charing Cross.”

RADIUM AGE SCIENCE FICTION: “Radium Age” is HILOBROW’s name for the 1904–33 era, which saw the discovery of radioactivity, the revelation that matter itself is constantly in movement — a fitting metaphor for the first decades of the 20th century, during which old scientific, religious, political, and social certainties were shattered. This era also saw the publication of genre-shattering writing by Edgar Rice Burroughs, Sax Rohmer, E.E. “Doc” Smith, Jack London, Arthur Conan Doyle, Aldous Huxley, Olaf Stapledon, Karel Čapek, H.P. Lovecraft, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Yevgeny Zamyatin, Philip Gordon Wylie, and other pioneers of post-Verne/Wells, pre-Golden Age “science fiction.” More info here.

HILOBOOKS: The mission of HiLoBooks is to serialize novels on HiLobrow; and also, as of 2012, operating as an imprint of Richard Nash’s Cursor, to reissue Radium Age science fiction in beautiful new print editions. So far, we have published Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague, Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”), Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt, H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook, Edward Shanks’s The People of the Ruins, William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land, and J.D. Beresford’s Goslings. Forthcoming: E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man, Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage, and Muriel Jaeger’s The Man with Six Senses. For more information, visit the HiLoBooks homepage.

READ: Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague, serialized between January and April 2012; Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”), serialized between March and June 2012; Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt, serialized between April and July 2012; and H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook, serialized between March and August 2012.

ORIGINAL FICTION: HILOBROW has serialized three novels: James Parker’s The Ballad of Cocky The Fox (“a proof-of-concept that serialization can work on the Internet” — The Atlantic) and Karinne Keithley Syers’s Linda Linda Linda. We also publish original stories and comics.