When the World Shook (13)

By:

June 1, 2012

HILOBROW is pleased to present the thirteenth installment of our serialization of H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook. New installments will appear each Friday for 24 weeks.

Marooned on a South Sea island, Humphrey Arbuthnot and his friends awaken the last two members of an advanced race, who have spent 250,000 years in a state of suspended animation. Using astral projection, Lord Oro visits London and the battlefields of the Western Front; horrified by the degraded state of modern civilization, he activates chthonic technology capable of obliterating it. Will Oro’s beautiful daughter, Yva, who has fallen in love with Humphrey, stop him in time?

“If this is pulp fiction it’s high pulp: a Wagnerian opera of an adventure tale, a B-movie humanist apocalypse and chivalric romance,” says Lydia Millet in a blurb written for HiLoBooks. “When the World Shook has it all — English gentlemen of leisure, a devastating shipwreck, a volcanic tropical island inhabited by cannibals, an ancient princess risen from the grave, and if that weren’t enough a friendly, ongoing debate between a godless materialist and a devout Christian. H. Rider Haggard’s rich universe is both profoundly camp and deeply idealistic.”

Haggard’s only science fiction novel was first published in 1919. In September 2012, HiLoBooks will publish a beautiful new edition of When the World Shook, with an introduction by Atlantic Monthly contributing editor James Parker. NOW AVAILABLE FOR PRE-ORDERING!

SUBSCRIBE to HILOBROW’s serialized fiction via RSS.

LAST WEEK: “‘You do not believe, O Bickley,’ she said, studying him gravely. ‘Indeed, you believe nothing. You think my father and I tell you many lies. Bastin there, he believes all. Humphrey? He is not sure; he thinks to himself, I will wait and find out whether or no these funny people cheat me.'”

ALL EXCERPTS: 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24

“Don’t choke me,” I heard Bickley say to Bastin, and the latter’s murmured reply of:

“I never could bear these moving staircases and tubelifts. They always make me feel sick.”

I admit that for my part I also felt rather sick and clung tightly to the hand of the Glittering Lady. She, however, placed her other hand upon my shoulder, saying in a low voice:

“Did I not tell you to have no fear?”

Then I felt comforted, for somehow I knew that it was not her desire to harm and much less to destroy me. Also Tommy was seated quite at his ease with his head resting against my leg, and his absence of alarm was reassuring. The only stoic of the party was Bickley. I have no doubt that he was quite as frightened as we were, but rather than show it he would have died.

“I presume this machinery is pneumatic,” he began when suddenly and without shock, we arrived at the end of our journey. How far we had fallen I am sure I do not know, but I should judge from the awful speed at which we travelled, that it must have been several thousand feet, probably four or five.

“Everything seems steady now,” remarked Bastin, “so I suppose this luggage lift has stopped. The odd thing is that I can’t see anything of it. There ought to be a shaft, but we seem to be standing on a level floor.”

“The odd thing is,” said Bickley, “that we can see at all. Where the devil does the light come from thousands of feet underground?”

“I don’t know,” answered Bastin, “unless there is natural gas here, as I am told there is at a town called Medicine Hat in Canada.”

“Natural gas be blowed,” said Bickley. “It is more like moonlight magnified ten times.”

So it was. The whole place was filled with a soft radiance, equal to that of the sun at noon, but gentler and without heat.

“Where does it come from?” I whispered to Yva.

“Oh!” she replied, as I thought evasively. “It is the light of the Under-world which we know how to use. The earth is full of light, which is not wonderful, is it, seeing that its heart is fire? Now look about you.”

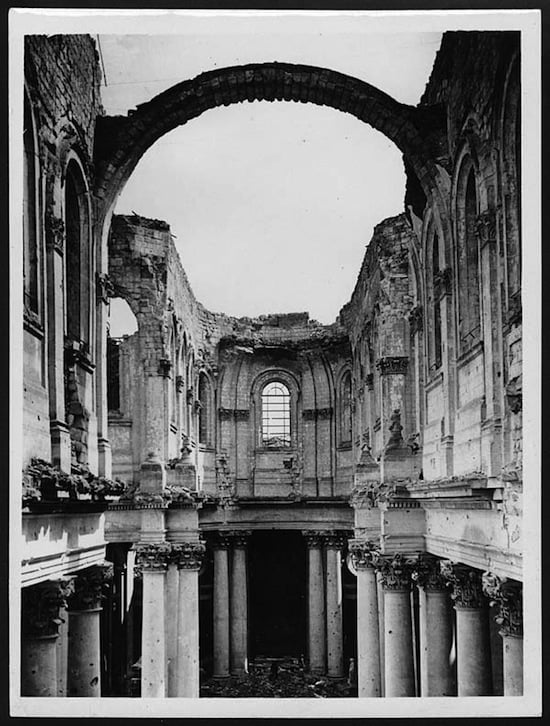

I looked and leant on her harder than ever, since amazement made me weak. We were in some vast place whereof the roof seemed almost as far off as the sky at night. At least all that I could make out was a dim and distant arch which might have been one of cloud. For the rest, in every direction stretched vastness, illuminated far as the eye could reach by the soft light of which I have spoken, that is, probably for several miles. But this vastness was not empty. On the contrary it was occupied by a great city. There were streets much wider than Piccadilly, all bordered by houses, though these, I observed, were roofless, very fine houses, some of them, built of white stone or marble. There were roadways and pavements worn by the passage of feet. There, farther on, were market-places or public squares, and there, lastly, was a huge central enclosure one or two hundred acres in extent, which was filled with majestic buildings that looked like palaces, or town-halls; and, in the midst of them all, a vast temple with courts and a central dome. For here, notwithstanding the lack of necessity, its builders seemed to have adhered to the Over-world tradition, and had roofed their fane.

And now came the terror. All of this enormous city was dead. Had it stood upon the moon it could not have been more dead. None paced its streets; none looked from its window-places. None trafficked in its markets, none worshipped in its temple. Swept, garnished, lighted, practically untouched by the hand of Time, here where no rains fell and no winds blew, it was yet a howling wilderness. For what wilderness is there to equal that which once has been the busy haunt of men? Let those who have stood among the buried cities of Central Asia, or of Anarajapura in Ceylon, or even amid the ruins of Salamis on the coast of Cyprus, answer the question. But here was something infinitely more awful. A huge human haunt in the bowels of the earth utterly devoid of human beings, and yet as perfect as on the day when these ceased to be.

“I do not care for underground localities,” remarked Bastin, his gruff voice echoing strangely in that terrible silence, “but it does seem a pity that all these fine buildings should be wasted. I suppose their inhabitants left them in search of fresh air.”

“Why did they leave them?” I asked of Yva.

“Because death took them,” she answered solemnly. “Even those who live a thousand years die at last, and if they have no children, with them dies the race.”

“Then were you the last of your people?” I asked.

“Inquire of my father,” she replied, and led the way through the massive arch of a great building.

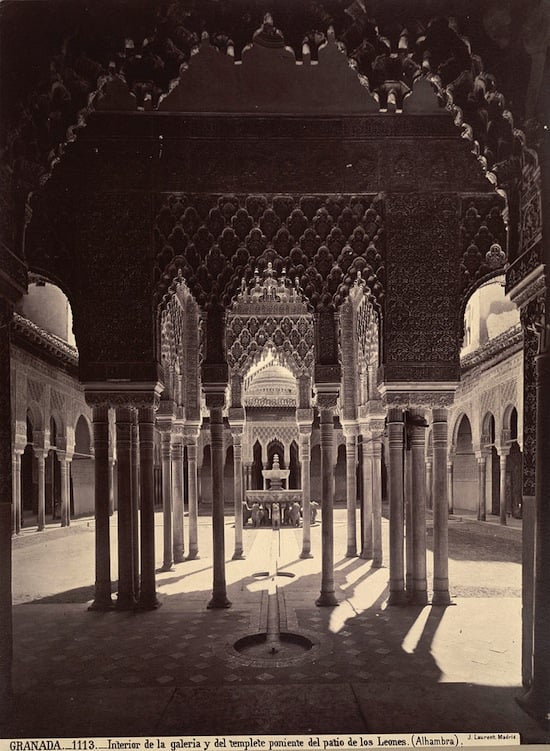

It led into a walled courtyard in the centre of which was a plain cupola of marble with a gate of some pale metal that looked like platinum mixed with gold. This gate stood open. Within it was the statue of a woman beautifully executed in white marble and set in a niche of some black stone. The figure was draped as though to conceal the shape, and the face was stern and majestic rather than beautiful. The eyes of the statue were cunningly made of some enamel which gave them a strange and lifelike appearance. They stared upwards as though looking away from the earth and its concerns. The arms were outstretched. In the right hand was a cup of black marble, in the left a similar cup of white marble. From each of these cups trickled a thin stream of sparkling water, which two streams met and mingled at a distance of about three feet beneath the cups. Then they fell into a metal basin which, although it must have been quite a foot thick, was cut right through by their constant impact, and apparently vanished down some pipe beneath. Out of this metal basin Tommy, who gambolled into the place ahead of us, began to drink in a greedy and demonstrative fashion.

“The Life-water?” I said, looking at our guide.

She nodded and asked in her turn:

“What is the statue and what does it signify, Humphrey?”

I hesitated, but Bastin answered:

“Just a rather ugly woman who hid up her figure because it was bad. Probably she was a relation of the artist who wished to have her likeness done and sat for nothing.”

“The goddess of Health,” suggested Bickley. “Her proportions are perfect; a robust, a thoroughly normal woman.”

“Now, Humphrey,” said Yva.

I stared at the work and had not an idea. Then it flashed on me with such suddenness and certainty that I am convinced the answer to the riddle was passed to me from her and did not originate in my own mind.

“It seems quite easy,” I said in a superior tone. “The figure symbolises Life and is draped because we only see the face of Life, the rest is hidden. The arms are bare because Life is real and active. One cup is black and one is white because Life brings both good and evil gifts; that is why the streams mingle, to be lost beneath in the darkness of death. The features are stern and even terrifying rather than lovely, because such is the aspect of Life. The eyes look upward and far away from present things, because the real life is not here.”

“Of course one may say anything,” said Bastin, “but I don’t understand all that.”

“Imagination goes a long way,” broke in Bickley, who was vexed that he had not thought of this interpretation himself. But Yva said:

“I begin to think that you are quite clever, Humphrey. I wonder whence the truth came to you, for such is the meaning of the figure and the cups. Had I told it to you myself, it could not have been better said,” and she glanced at me out of the corners of her eyes. “Now, Strangers, will you drink? Once that gate was guarded, and only at a great price or as a great reward were certain of the Highest Blood given the freedom of this fountain which might touch no common lips. Indeed it was one of the causes of our last war, for all the world which was, desired this water which now is lapped by a stranger’s hound.”

“I suppose there is nothing medicinal in it?” said Bastin. “Once when I was very thirsty, I made a mistake and drank three tumblers of something of the sort in the dark, thinking that it was Apollinaris, and I don’t want to do it again.”

“Just the sort of thing you would do,” said Bickley. “But, Lady Yva, what are the properties of this water?”

“It is very health-giving,” she answered, “and if drunk continually, not less than once each thirty days, it wards off sickness, lessens hunger and postpones death for many, many years. That is why those of the High Blood endured so long and became the rulers of the world, and that, as I have said, is the greatest of the reasons why the peoples who dwelt in the ancient outer countries and never wished to die, made war upon them, to win this secret fountain. Have no fear, O Bastin, for see, I will pledge you in this water.”

Then she lifted a strange-looking, shallow, metal cup whereof the handles were formed of twisted serpents, that lay in the basin, filled it from the trickling stream, bowed to us and drank. But as she drank I noted with a thrill of joy that her eyes were fixed on mine as though it were me she pledged and me alone. Again she filled the cup with the sparkling water, for it did sparkle, like that French liqueur in which are mingled little flakes of gold, and handed it to me.

I bowed to her and drank. I suppose the fluid was water, but to me it tasted more like strong champagne, dashed with Chateau Yquem. It was delicious. More, its effects were distinctly peculiar. Something quick and subtle ran through my veins; something that for a few moments seemed to burn away the obscureness which blurs our thought. I began to understand several problems that had puzzled me, and then lost their explanations in the midst of light, inner light, I mean. Moreover, of a sudden it seemed to me as though a window had been opened in the heart of that Glittering Lady who stood beside me. At least I knew that it was full of wonderful knowledge, wonderful memories and wonderful hopes, and that in the latter two of these I had some part; what part I could not tell. Also I knew that my heart was open to her and that she saw in it something which caused her to marvel and to sigh.

In a few seconds, thirty perhaps, all this was gone. Nothing remained except that I felt extremely strong and well, happier, too, than I had been for years. Mutely I asked her for more of the water, but she shook her head and, taking the cup from me, filled it again and gave it to Bickley, who drank. He flushed, seemed to lose the self-control which was his very strong characteristic, and said in a rather thick voice:

“Curious! but I do not think at this moment there is any operation that has ever been attempted which I could not tackle single-handed and with success.”

Then he was silent, and Bastin’s turn came. He drank rather noisily, after his fashion, and began:

“My dear young lady, I think the time has come when I should expound to you —” Here he broke off and commenced singing very badly, for his voice was somewhat raucous:

From Greenland’s icy mountains,

From India’s coral strand,

Where Afric’s sunny fountains

Roll down their golden sand.

Ceasing from melody, he added:

“I determined that I would drink nothing intoxicating while I was on this island that I might be a shining light in a dark place, and now I fear that quite unwittingly I have broken what I look upon as a promise.”

Then he, too, grew silent.

“Come,” said Yva, “my father, the Lord Oro, awaits you.”

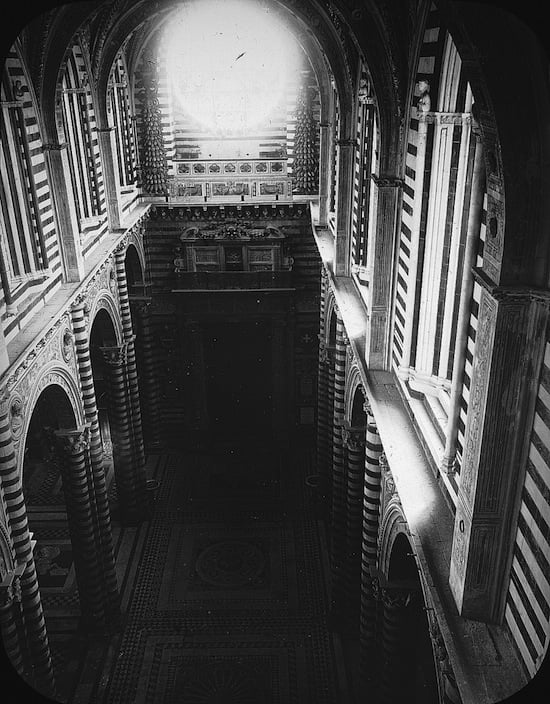

We crossed the court of the Water of Life and mounted steps that led to a wide and impressive portico, Tommy frisking ahead of us in a most excited way for a dog of his experience. Evidently the water had produced its effect upon him as well as upon his masters. This portico was in a solemn style of architecture which I cannot describe, because it differed from any other that I know. It was not Egyptian and not Greek, although its solidity reminded me of the former, and the beauty and grace of some of the columns, of the latter. The profuseness and rather grotesque character of the carvings suggested the ruins of Mexico and Yucatan, and the enormous size of the blocks of stone, those of Peru and Baalbec. In short, all the known forms of ancient architecture might have found their inspiration here, and the general effect was tremendous.

“The palace of the King,” said Yva, “whereof we approach the great hall.”

We entered through mighty metal doors, one of which stood ajar, into a vestibule which from certain indications I gathered had once been a guard, or perhaps an assembly-room. It was about forty feet deep by a hundred wide. Thence she led us through a smaller door into the hall itself. It was a vast place without columns, for there was no roof to support. The walls of marble or limestone were sculptured like those of Egyptian temples, apparently with battle scenes, though of this I am not sure for I did not go near to them. Except for a broad avenue along the middle, up which we walked, the area was filled with marble benches that would, I presume, have accommodated several thousand people. But they were empty — empty, and oh! the loneliness of it all.

Far away at the head of the hall was a dais enclosed, and, as it were, roofed in by a towering structure that mingled grace and majesty to a wonderful degree. It was modelled on the pattern of a huge shell. The base of the shell was the platform; behind were the ribs, and above, the overhanging lip of the shell. On this platform was a throne of silvery metal. It was supported on the arched coils of snakes, whereof the tails formed the back and the heads the arms of the throne.

On this throne, arrayed in gorgeous robes, sat the Lord Oro, his white beard flowing over them, and a jewelled cap upon his head. In front of him was a low table on which lay graven sheets of metal, and among them a large ball of crystal.

There he sat, solemn and silent in the midst of this awful solitude, looking in very truth like a god, as we conceive such a being to appear. Small as he was in that huge expanse of buildings, he seemed yet to dominate it, in a sense to fill the emptiness which was accentuated by his presence. I know that the sight of him filled me with true fear which it had never done in the light of day, not even when he arose from his crystal coffin. Now for the first time I felt as though I were really in the presence of a Being Supernatural. Doubtless the surroundings heightened this impression. What were these mighty edifices in the bowels of the world? Whence came this wondrous, all-pervading and translucent light, whereof we could see no origin? Whither had vanished those who had reared and inhabited them? How did it happen that of them all, this man, if he were a man; and this lovely woman at my side, who, if I might trust my senses and instincts, was certainly a woman, alone survived of their departed multitudes?

The thing was crushing. I looked at Bickley for encouragement, but got none, for he only shook his head. Even Bastin, now that the first effects of the Life-water had departed, seemed overwhelmed, and muttered something about the halls of Hades.

Only the little dog Tommy remained quite cheerful. He trotted down the hall, jumped on to the dais and sat himself comfortably at the feet of its occupant.

“I greet you,” Oro said in his slow, resonant voice. “Daughter, lead these strangers to me; I would speak with them.”

ORO IN HIS HOUSE

We climbed on to the dais by some marble steps, and sat ourselves down in four curious chairs of metal that were more or less copied from that which served Oro as a throne; at least the arms ended in graven heads of snakes. These chairs were so comfortable that I concluded the seats were fixed on springs, also we noticed that they were beautifully polished.

“I wonder how they keep everything so clean,” said Bastin as we mounted the dais. “In this big place it must take a lot of housemaids, though I don’t see any. But perhaps there is no dust here.”

I shrugged my shoulders while we seated ourselves, the Lady Yva and I on Oro’s right, Bickley and Bastin on his left, as he indicated by pointing with his finger.

“What say you of this city?” Oro asked after a while of me.

“We do not know what to say,” I replied. “It amazes us. In our world there is nothing like to it.”

“Perchance there will be in the future when the nations grow more skilled in the arts of war,” said Oro darkly.

“Be pleased, Lord Oro,” I went on, “if it is your will, to tell us why the people who built this place chose to live in the bowels of the earth instead of upon its surface.”

“They did not choose; it was forced upon them,” was the answer. “This is a city of refuge that they occupied in time of war, not because they hated the sun. In time of peace and before the Barbarians dared to attack them, they dwelt in the city Pani which signifies Above. You may have noted some of its remaining ruins on the mount and throughout the island. The rest of them are now beneath the sea. But when trouble came and the foe rained fire on them from the air, they retreated to this town, Nyo, which signifies Beneath.”

“And then?”

“And then they died. The Water of Life may prolong life, but it cannot make women bear children. That they will only do beneath the blue of heaven, not deep in the belly of the world where Nature never designed that they should dwell. How would the voices of children sound in such halls as these? Tell me, you, Bickley, who are a physician.”

“I cannot. I cannot imagine children in such a place, and if born here they would die,” said Bickley.

Oro nodded.

“They did die, and if they went above to Pani they were murdered. So soon the habit of birth was lost and the Sons of Wisdom perished one by one. Yes, they who ruled the world and by tens of thousands of years of toil had gathered into their bosoms all the secrets of the world, perished, till only a few, and among them I and this daughter of mine, were left.”

“And then?”

“Then, Humphrey, having power so to do, I did what long I had threatened, and unchained the forces that work at the world’s heart, and destroyed them who were my enemies and evil, so that they perished by millions, and with them all their works. Afterwards we slept, leaving the others, our subjects who had not the secret of this Sleep, to die, as doubtless they did in the course of Nature or by the hand of the foe. The rest you know.”

“Can such a thing happen again?” asked Bickley in a voice that did not hide his disbelief.

“Why do you question me, Bickley, you who believe nothing of what I tell you, and therefore make wrath? Still I will say this, that what I caused to happen I can cause once more — only once, I think — as perchance you shall learn before all is done. Now, since you do not believe, I will tell you no more of our mysteries, no, not whence this light comes nor what are the properties of the Water of Life, both of which you long to know, nor how to preserve the vital spark of Being in the grave of dreamless sleep, like a live jewel in a casket of dead stone, nor aught else. As to these matters, Daughter, I bid you also to be silent, since Bickley mocks at us. Yes, with all this around him, he who saw us rise from the coffins, still mocks at us in his heart. Therefore let him, this little man of a little day, when his few years are done go to the tomb in ignorance, and his companions with him, they who might have been as wise as I am.”

Thus Oro spoke in a voice of icy rage, his deep eyes glowing like coals. Hearing him I cursed Bickley in my heart for I was sure that once spoken, his decree was like to that of the Medes and Persians and could not be altered. Bickley, however, was not in the least dismayed. Indeed he argued the point. He told Oro straight out that he would not believe in the impossible until it had been shown to him to be possible, and that the law of Nature never had been and never could be violated. It was no answer, he said, to show him wonders without explaining their cause, since all that he seemed to see might be but mental illusions produced he knew not how.

Oro listened patiently, then answered:

“Good. So be it, they are illusions. I am an illusion; those savages who died upon the rock will tell you so. This fair woman before you is an illusion; Humphrey, I am sure, knows it as you will also before you have done with her. These halls are illusions. Live on in your illusions, O little man of science, who because you see the face of things, think that you know the body and the heart, and can read the soul at work within. You are a worthy child of tens of thousands of your breed who were before you and are now forgotten.”

Bickley looked up to answer, then changed his mind and was silent, thinking further argument dangerous, and Oro went on:

“Now I differ from you, Bickley, in this way. I who have more wisdom in my finger-point than you with all the physicians of your world added to you, have in your brains and bodies, yet desire to learn from those who can give me knowledge. I understand from your words to my daughter that you, Bastin, teach a faith that is new to me, and that this faith tells of life eternal for the children of earth. Is it so?”

“It is,” said Bastin eagerly. “I will set out —”

Oro cut him short with a wave of the hand.

“Not now in the presence of Bickley who doubtless disbelieves your faith, as he does all else, holding it with justice or without, to be but another illusion. Yet you shall teach me and on it I will form my own judgment.”

“I shall be delighted,” said Bastin. Then a doubt struck him, and he added: “But why do you wish to learn? Not that you may make a mock of my religion, is it?”

“I mock at no man’s belief, because I think that what men believe is true — for them. I will tell you why I wish to hear of yours, since I never hide the truth. I who am so wise and old, yet must die; though that time may be far away, still I must die, for such is the lot of man born of woman. And I do not desire to die. Therefore I shall rejoice to learn of any faith that promises to the children of earth a life eternal beyond the earth. Tomorrow you shall begin to teach me. Now leave me, Strangers, for I have much to do,” and he waved his hand towards the table.

We rose and bowed, wondering what he could have to do down in this luminous hole, he who had been for so many thousands of years out of touch with the world. It occurred to me, however, that during this long period he might have got in touch with other worlds, indeed he looked like it.

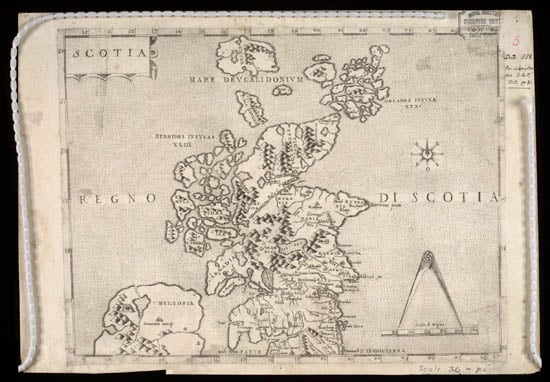

“Wait,” he said, “I have something to tell you. I have been studying this book of writings, or world pictures,” and he pointed to my atlas which, as I now observed for the first time, was also lying upon the table. “It interests me much. Your country is small, very small. When I caused it to be raised up I think that it was larger, but since then that seas have flowed in.”

Here Bickley groaned aloud.

“This one is much greater,” went on Oro, casting a glance at Bickley that must have penetrated him like a searchlight. Then he opened the map of Europe and with his finger indicated Germany and Austria-Hungary. “I know nothing of the peoples of these lands,” he added, “but as you belong to one of them and are my guests, I trust that yours may succeed in the war.”

“What war?” we asked with one voice.

“Since Bickley is so clever, surely he should know better than an illusion such as I. All I can tell you is that I have learned that there is war between this country and that,” and he pointed to Great Britain and to Germany upon the map; “also between others.”

“It is quite possible,” I said, remembering many things. “But how do you know?”

“If I told you, Humphrey, Bickley would not believe, so I will not tell. Perhaps I saw it in that crystal, as did the necromancers of the early world. Or perhaps the crystal serves some different purpose and I saw it otherwise — with my soul. At least what I say is true.”

“Then who will win?” asked Bastin.

“I cannot read the future, Preacher. If I could, should I ask you to expound to me your religion which probably is of no more worth than a score of others I have studied, just because it tells of the future? If I could read the future I should be a god instead of only an earth-lord.”

“Your daughter called you a god and you said that you knew we were coming to wake you up, which is reading the future,” answered Bastin.

“Every father is a god to his daughter, or should be; also in my day millions named me a god because I saw further and struck harder than they could. As for the rest, it came to me in a vision. Oh! Bickley, if you were wiser than you think you are, you would know that all things to come are born elsewhere and travel hither like the light from stars. Sometimes they come faster before their day into a single mind, and that is what men call prophecy. But this is a gift which cannot be commanded, even by me. Also I did not know that you would come. I knew only that we should awaken and by the help of men, for if none had been present at that destined hour we must have died for lack of warmth and sustenance.”

“I deny your hypothesis in toto,” exclaimed Bickley, but nobody paid any attention to him.

“My father,” said Yva, rising and bowing before him with her swan-like grace, “I have noted your commands. But do you permit that I show the temple to these strangers, also something of our past?”

“Yes, yes,” he said. “It will save much talk in a savage tongue that is difficult to me. But bring them here no more without my command, save Bastin only. When the sun is four hours high in the upper world, let him come tomorrow to teach me, and afterwards if so I desire. Or if he wills, he can sleep here.”

“I think I would rather not,” said Bastin hurriedly. “I make no pretense to being particular, but this place does not appeal to me as a bedroom. There are degrees in the pleasures of solitude and, in short, I will not disturb your privacy at night.”

Oro waved his hand and we departed down that awful and most dreary hall.

“I hope you will spend a pleasant time here, Bastin,” I said, looking back from the doorway at its cold, illuminated vastness.

“I don’t expect to,” he answered, “but duty is duty, and if I can drag that old sinner back from the pit that awaits him, it will be worth doing. Only I have my doubts about him. To me he seems to bear a strong family resemblance to Beelzebub, and he’s a bad companion week in and week out.”

NEXT WEEK: “‘The Lord Oro motions with his hand to the guard. They lift their death-rods. Fire leaps from them. The Prince and his companions, all save those who were afraid and would have sworn the oath, twist and writhe. They turn black; they die. The Lord Oro commands those who are left to enter their flying ships and bear to the Nations of the Earth tidings of what befalls those who dare to defy and insult him; to warn them also to eat and drink and be merry while they may, since for their wickedness they are about to perish.'”

RADIUM AGE SCIENCE FICTION: “Radium Age” is HILOBROW’s name for the 1904–33 era, which saw the discovery of radioactivity, the revelation that matter itself is constantly in movement — a fitting metaphor for the first decades of the 20th century, during which old scientific, religious, political, and social certainties were shattered. This era also saw the publication of genre-shattering writing by Edgar Rice Burroughs, Sax Rohmer, E.E. “Doc” Smith, Jack London, Arthur Conan Doyle, Aldous Huxley, Olaf Stapledon, Karel Čapek, H.P. Lovecraft, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Yevgeny Zamyatin, Philip Gordon Wylie, and other pioneers of post-Verne/Wells, pre-Golden Age “science fiction.” More info here.

HILOBOOKS: The mission of HiLoBooks is to serialize novels on HiLobrow; and also, as of 2012, operating as an imprint of Richard Nash’s Cursor, to reissue Radium Age science fiction in beautiful new print editions. So far, we have published Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague, Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”), Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt, H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook, Edward Shanks’s The People of the Ruins, William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land, and J.D. Beresford’s Goslings. Forthcoming: E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man, Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage, and Muriel Jaeger’s The Man with Six Senses. For more information, visit the HiLoBooks homepage.

READ: You are reading H. Rider Haggard’s When The World Shook. Also read our serialization of: Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague | Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail and “As Easy As A.B.C.” | Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt

ORIGINAL FICTION: HILOBROW has serialized three novels: James Parker’s The Ballad of Cocky The Fox (“a proof-of-concept that serialization can work on the Internet” — The Atlantic) and Karinne Keithley Syers’s Linda Linda Linda. We also publish original stories and comics.