The People of the Ruins (2)

By:

May 31, 2012

HILOBROW is pleased to present the second installment of our serialization of Edward Shanks’ The People of the Ruins: A Story of the English Revolution and After. New installments will appear each Thursday for 16 weeks.

Trapped in a London laboratory during a worker uprising in 1924, ex-artillery officer and physics instructor Jeremy Tuft awakens 150 years later — in a neo-medieval society whose inhabitants have forgotten how to build or operate machinery. Not only have his fellow Londoners forgotten most of what humankind used to know, before civilization collapsed, but they don’t particularly care to re-learn any of it. Though he is at first disconcerted by the failure of his own era’s smug doctrine of Progress, Tuft eventually decides that post-civilized life is simpler, more peaceful. That is, until northern English and Welsh tribes threaten London — at which point he sets about reinventing weapons of mass destruction.

Shanks’ post-apocalyptic novel, a pessimistic satire on Wellsian techno-utopian novels, was first published in 1920. In October, HiLoBooks will publish a beautiful new edition of The People of the Ruins, with an introduction by Tom Hodgkinson.

SUBSCRIBE to HILOBROW’s serialized fiction via RSS.

LAST WEEK: “He had not been able to believe that a time would ever come when there would be no Government, no Paymaster-General, no Ministry of Pensions, to pay him his partial disability pension. But this morning unexpected events seemed much more probable. There was not much of the world to be perceived from his window looking down the street, but what there was smelt somehow remarkably like real trouble.”

ALL EXCERPTS: 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 |15 |16

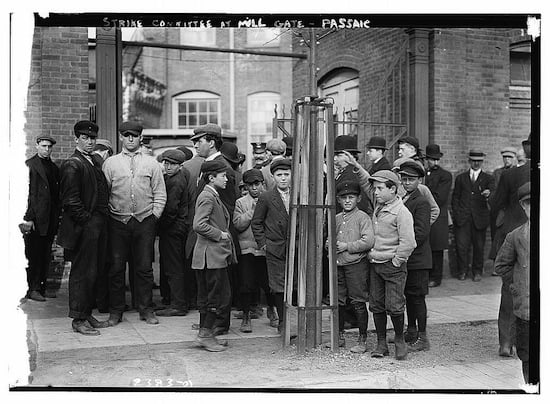

THE DEAD RAT

As he came closer to Whitechapel High Street, Jeremy found with surprise and some addition to his uneasiness, that this district had a more wakeful and week-day appearance. Many of the shops and eating-houses were open; and the Government order, issued two days before, forbidding the sale of liquor while the strike menace endured, was being frankly disregarded. This was the first use that had been made of the Public Order (Preservation of) Act, passed hurriedly and almost in secret two or three months before; and Jeremy, enquiring what his own feelings would have been if he had been in a like position to the restless workmen, had been stirred out of his ordinary political indifference to call it unwise. He might have been stirred to even greater feeling about the original Act if he had known that it was principally this against which the strikes were directed. But he had omitted to ask why the unions were striking, and no one had told him. The middle classes of those days had got used to unintelligible and apparently senseless upheavals. Now, as he passed by one public-house after another, all open, and saw the crowds inside and round the doors, conversing with interest and perceptibly rising excitement on only one topic, he rather wished that the order could have been enforced. There was something sinister in the silence which fell where he passed. He felt uncomfortably that he was being looked at with suspicion.

He turned out of the wide road, now empty of all wheeled traffic, except for a derelict tramcar which stood desolate, apparently where driver and conductor had struck work earlier or later than their fellows. In the side street which led to his destination, there were mostly women — dark, ugly, alien women — sitting on their doorsteps; and he began to feel even more afraid of them than of the men. They did not lower their voices as he passed, but he could not understand I what they were saying. But as he swung with a distinct sense of relief into the little narrow court where Trehanoc absurdly lived and had his laboratory, he heard one of them call after him, “Dir-r-rty bour-rgeois!” and all the rest laugh ominously together. The repetition of the phrase in this new accent startled him and he fretted at the door because Trehanoc did not immediately answer his knock.

“Damn you for living down here!” he said heartily, when Trehanoc at last opened to him. “I don’t like your neighbors at all.”

“I know… I know…,” Trehanoc answered apologetically. “But how could I expect — And anyway they’re nice people really when you get to know them. I get on very well with them.” He paused and looked with some apprehension at Jeremy’s annoyed countenance.

He was a Cornishman, a tall, loose, queerly excitable and eccentric fellow, with whom, years before, Jeremy had worked in the laboratories at University College. He had taken his degree — just taken it — and this result, while not abating his strange passion for research in physics, seemed to have destroyed forever all hope of his indulging it. After that no one knew what he had done, until a distant relative had died and left him a few hundreds a year and the empty warehouse in Lime Court. He had accepted the legacy as a direct intervention of providence, refused the specious offers of a Hebrew dealer in fur coats, and had fitted up the crazy building as a laboratory, with a living-room or two, where he spent vastly exciting hours pursuing with the sketchiest of home-made apparatus the abstrusest of natural mysteries. One or two old acquaintances of the Gower Street days had run across him here and there, and, on confessing that they were still devoted to science, had been urgently invited to pay a visit to Whitechapel. They had returned, half-alarmed, half-amused, and had reported that Trehanoc was madder than ever, and was attempting the transmutation of the elements with a home-made electric coil, an old jam-jar, and a biscuit tin. They also reported that his neighborhood was rich in disagreeable smells and that his laboratory was inhabited by rats.

But Jeremy’s taste in acquaintances was broad and comprehensive, always provided that they escaped growing tedious. After his first visit to Lime Court he had not been slow in paying a second. His acquaintance ripened into friendship with Trehanoc, whom he regarded, perhaps only half-consciously, as being an inspired, or at any rate an exceedingly lucky, fool. When he received an almost illegible and quite incoherent summons to go and see a surprising new experiment, “something,” as the fortunate discoverer put it, “very funny,” he had at once promised to go. It was characteristic of him that, having promised, he went, although he had to walk through disturbed London, arrived grumbling, and reassured his anxious host without once ceasing to complain of the inconvenience he had suffered.

“I ought to tell you,” Trehanoc said, with increased anxiety when Jeremy paused to take breath, “that a man’s dropped in to lunch. I didn’t ask him, and he isn’t a scientist, and he talks rather a lot, but — but — I don’t suppose he’ll be much in the way,” he finished breathlessly.

“All right, Augustus,” Jeremy replied in a more resigned tone, and with a soothing wave of his hand, “carry on. I don’t suppose one extra useless object in one of your experiments will make any particular difference.”

He followed Trehanoc with lumbering speed up the narrow, uncarpeted stairs and into the big loft which served for living-room and kitchen combined. There he saw the useless object stretched on a couch — a pleasant youth of rather disheveled appearance, who raised his head and said lazily:

“Hullo! It’s you, is it? We met last night, but I don’t suppose you remember that.”

“No, I don’t,” said Jeremy shortly.

“No, I thought you wouldn’t. My name’s Maclan. You must have known that last night, because you told me twice that no man whose name began with Mac ever knew when he was boring the company.”

“Did I?” Jeremy looked a little blank, and then began to brighten. “Of course. You were the man who was talking about the General Strike being a myth. I hope I didn’t hurt your feelings too much?”

“Not at all. I knew you meant well; and, after all, you weren’t in a condition to realize what I was up to. The secret of it all was that by boring all the rest of the company till they wanted to scream I was very effectually preventing them from boring me. You see, I saw at once that the politicians had taken the floor for the rest of the evening, and I knew that the only way to deal with them was to irritate them on their own ground. It was rather good sport really, only, of course, you couldn’t be expected to see the point of it.”

Jeremy began to chuckle with appreciation. “Very good,” he agreed. “Very good. I wish I’d known.” And Trehanoc, who had been hovering behind him uneasily, holding a frying-pan, said with a deep breath of relief: “That’s all right, then.”

“What the devil’s the matter with you, Augustus?” Jeremy cried, wheeling round on him. “What do you mean, ‘That’s all right, then’?”

“I was only afraid you two chaps would quarrel,” he explained. “You’re both of you rather difficult to get on with.” And he disappeared with the frying-pan into the corner which was curtained off for cooking.

“Old Trehanoc’s delightfully open about everything,” Maclan observed, stretching himself and lighting a cigarette. “I suppose we all of us have to apologize for a friend to another now and again, but he’s the only man I ever met that did it in the presence of both. It’s the sort of thing that makes a man distinctive.”

Lunch was what the two guests might have expected, and probably did. The sausages would no doubt have been more successful if Trehanoc had remembered to provide either potatoes or bread; but his half-hearted offer of a little uncooked oatmeal was summarily rejected. Jeremy’s appetite, however, was reviving, and Maclan plainly cared very little what he ate. His interest lay rather in talking; and throughout the meal he discoursed to a stolidly masticating Jeremy and a nervous, protesting Trehanoc on the theme that civilization had reached and passed its climax and was hurrying into the abyss. He instanced the case of Russia.

“Russia,” he said, leaning over towards the Cornishman and marking his points with flourishes of a fork, “Russia went so far that she couldn’t get back. For a long time they shouted for the blockade to be raised so that they could get machinery for their factories and their railways. Now they’ve been without it so long they don’t want it any more. Oh, of course, they still talk about reconstruction and rebuilding the railways and so forth, but it’ll never happen. It’s too late. They’ve dropped down a stage; and there they’ll stop, unless they go lower still, as they are quite likely to.”

Trehanoc looked up with a fanatical gleam in his big brown eyes, which faded as he saw Maclan, poised and alert, waiting for him, and Jeremy quietly eating with the greatest unconcern. “I don’t care what you say,” he muttered sullenly, dropping his head again. “There’s no limit to what science can do. Look what we’ve done in the last hundred years. We shall discover the origin of matter, and how to transmute the elements; we shall abolish disease… and there’s my discovery —”

“But, my dear man,” Maclan interrupted, “just because we’ve done this, that, and the other in the last hundred years, there’s no earthly reason for supposing that we shall go on doing it. You don’t allow for the delicacy of all these things or for the brutality of the forces that are going to break them up. Why, if you got the world really in a turmoil for thirty years, at the end of that time you wouldn’t be able to find a man who could mend your electric light, and you’d have forgotten how to do it yourself. And you don’t allow for the fact that we ourselves change… What do you say, Tuft? You’re a scientist, too.”

“The present state of our knowledge,” Jeremy replied cheerfully with his mouth full, “doesn’t justify prophecies.”

“Ah! our knowledge… no, perhaps not. But our intuitions!” And here, as he spoke, Maclan seemed to grow for a moment a little more serious. “Don’t you know there’s a moment in anything — a holiday, or a party, or a love-affair, or whatever you like — when you feel that you’ve reached the climax, and that there’s nothing more to come. I feel that now. Oh! it’s been a good time, and we seemed to be getting freer and freer and richer and richer. But now we’ve got as far as we can and everything changes… Change here for the Dark Ages!” he added with a sudden alteration in his manner. “In fact, if I may put it so, this is where we get out and walk.”

Jeremy looked at him, wondering vaguely how much of this was genuine and how much mere discourse. He thought that, whichever it was, on the whole he disliked it. “Oh! we shall go jogging on just as usual,” he said at last, as matter-of-fact as he could.

“Oh, no, we sha’n’t!” Maclan returned with equal coolness. “We shall go to eternal smash.”

Trehanoc looked up again from the food he had been wolfing down with absent-minded ferocity. “It doesn’t matter what either of you thinks,” he affirmed earnestly. “There’s no limit to what we are going to do. We —” A dull explosion filled their ears and shook the windows.

“And what in hell’s that?” cried Jeremy.

For a moment all three of them sat rigid, staring instinctively out of the windows, whence nothing could be seen save the waving branches of the tree that gave its name to Lime Court. Maclan at last broke the silence.

“The Golden Age,” he said solemnly, “has tripped over the mat. Hadn’t we better go and see what’s happened to it?”

“Don’t be a fool!” Jeremy ejaculated. “If there really is trouble these streets won’t be too pleasant, and we’d better not draw attention to ourselves.” Immediately in the rear of his words came the confused noise of many people running and shouting. It was the mixed population of Whitechapel going to see what was up; and before many of them could have done so, the real fighting must have begun. The sound of firing, scattered and spasmodic, punctuated by the dull, vibrating bursts which Jeremy recognized for bombs, came abruptly to the listeners in the warehouse. There was an opening and shutting of windows and a banging of doors, men shouting and women crying, as though suddenly the whole district had been set in motion. All this gradually died away again and left to come sharper and clearer the incessant noise of the rifles and the bombs.

“Scott has set them going,” Jeremy murmured to, himself, almost content in the fulfilment of a prophecy, and then he said aloud: “Have you got any cigarettes, Augustus? I can’t say we’re well off where we are, but we’ve got to stop for a bit.”

Trehanoc produced a tin of Virginians which he offered to his guests. “I’m afraid,” he said miserably, “that this isn’t a very good time for asking you to have a look at my experiment.” Jeremy surveyed him with a curious eye, and reflected that the contrast in the effect of the distant firing on the three of them was worth observation. He himself did not pretend to like it, but knew that nothing could be done, and so endured it stoically. Maclan had settled in an armchair with a cigarette and a very tattered copy of La Vie Parisienne, and was giving an exhibition of almost flippant unconcern; but every time there was a louder burst of fire his shoulders twitched slightly. Trehanoc’s behavior was the most interesting of all. He had been nervous and excited while they were at table, and the explosion had obviously accentuated his condition. But he had somehow turned his excitement into the channel of his discovery, and his look of hungry and strained disappointment was pathetic to witness. It touched Jeremy’s heart, and moved him to say as heartily as he could:

“Nonsense, old fellow. We’ll come along and see it in a moment. What’s it all about?”

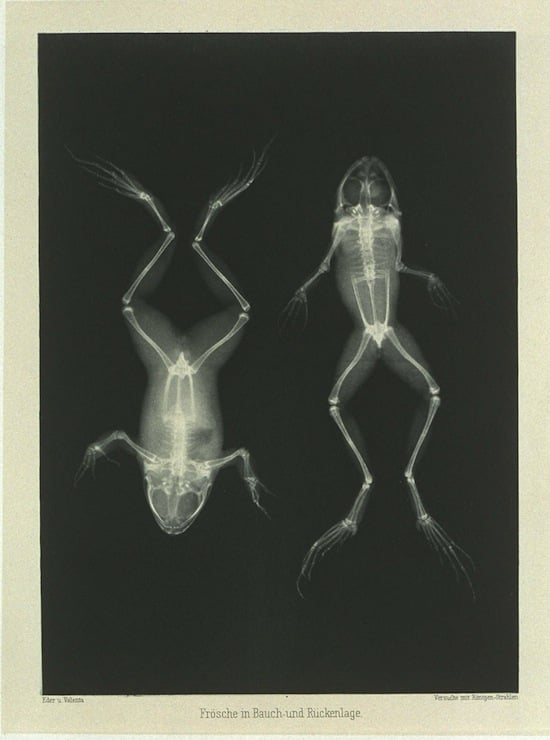

Trehanoc murmured “Thanks awfully…I was afraid you wouldn’t want…”— like a child who has feared that the party would not take place after all. Then he sat down sprawlingly in a chair and fixed his wild, shining eyes on Jeremy’s face. “You see,” he began, “I think it’s a new ray. I’m almost certain it’s a new ray. But I’m not quite certain how I got it. I’ll show you all that later. But it’s something like the ray that man used to change bacilli. He changed bacilli into cocci, or something. I’m no biologist; I was going to get in a biologist when you’d helped me a bit. You remember the experiment I mean, don’t you?”

“Vaguely,” said Jeremy. “It’s a bit out of my line, but my recollection is that he used alpha rays. However, go on.”

“Well, that’s what I was after,” Trehanoc continued. “I believe these rays do something of the same kind, and they’ve got other properties I don’t understand. There’s the rat… but I’ll show you the rat later on. And then I got my hand in front of the vacuum-tube for half a second without any protection…”

“Did you get a burn?” Jeremy asked sharply.

“No,” said Trehanoc. “No… I didn’t… that’s the strange thing. I’d got a little radium burn on that hand already, and a festering cut as well, where I jabbed myself with the tin-opener… Well, first of all, my hand went queer. It was a sort of dead, numb feeling, spreading into the arm above the wrist, and I was scared, I can tell you. I was almost certain that these were new rays, and I hadn’t the least notion what effect they might have on living tissue. The numbness kept on all day, with a sort of tingling in the finger-tips, and I went to bed in a bit of a panic. And when I woke, the radium burn had quite gone, leaving a little scar behind, and the cut had begun to heal. It was very nearly healed!”

“Quite sure it’s a new ray?” Jeremy interjected.

“Oh, very nearly sure. You see, I—” and he entered into a long and highly technical argument which left Jeremy both satisfied and curious. At the close of it Maclan remarked in a tone of deep melancholy:

“Tre, my old friend, if the experiment isn’t more exciting than the lecture, I shall go out and take my turn on the barricades. I got lost at the point where you began talking about electrons. Do, for heaven’s sake, let’s go and see your hell-broth!”

“Would you like to go and see it now?” Trehanoc asked, watching Jeremy’s face with solicitous anxiety; and receiving assent he led the way at once, saying, “You know, I use the cellar for this radio-active work. The darkness… And by the way,” he interrupted himself, “look out how you go. This house is in a rotten state of repair.” The swaying of the stairs down from the loft, when all three were upon them, confirmed him alarmingly.

As they went past the front-door towards the cellar-steps, Jeremy, cocking his head sideways, thought that every now and then some of the shots rang out much louder, as though the skirmishing was getting close to Lime Court. But he was by now deeply interested in Trehanoc’s experiment, and followed without speaking.

When they came down into the cellar Trehanoc touched a switch and revealed a long room, lit only in the nearer portion, where electric bulbs hung over two great laboratory tables and stretching away into clammy darkness.

“Here it is,” he said nervously, indicating the further of the two tables, and hung on Jeremy’s first words.

Jeremy’s first words were characteristic. “How you ever get any result at all,” he said, slowly and incisively, “is more than I can make out. This table looks as though some charwoman had been piling rubbish on it.”

“Yes, I know… I know. . .” Trehanoc admitted in a voice of shame. “That’s where I wanted you to help me. You see, I can’t be quite sure exactly what it is that does determine the result. There’s the vacuum-tube, worked by a coil, and there’s an electric magnet… and that tube on the other side has got radium-emanation in it…”

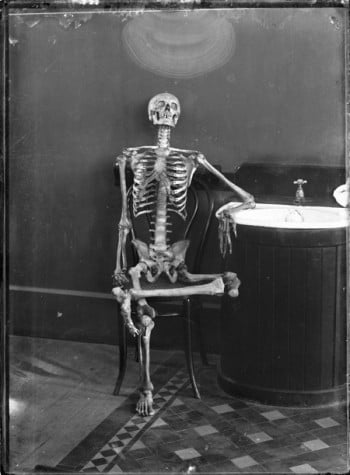

“And then there’s the dead rat,” Jeremy interrupted rather brutally. “What about the dead rat? Does that affect the result?” He pointed with a forefinger, expressing some disgust, to a remarkably sleek and well-favored corpse which decorated the end of the table.

“I was going to tell you…” Trehanoc muttered, twisting one hand in the other. “You know, there are rather a lot of rats in this cellar —”

“I know,” said Jeremy.

“And when I was making the first experiment that chap jumped on to the table and ran across in front of the vacuum-tube —”

“Well?”

“And he just dropped like that, dropped dead in his tracks… and… and I was frightfully excited, so I only picked him up by his tail and threw him away and forgot all about him. And then quite a long time afterwards, when I was looking for something, I came across him, just like that, just as fresh —”

“And when was that?” Jeremy asked.

“It must be quite six weeks since I made that first experiment.”

“So he’s one of the exhibits,” Jeremy began slowly. But a new outbreak of firing, unmistakably closer at hand, broke across his sentence. Maclan, who was beginning to find the rat a little tedious, and had been hoping that Trehanoc would soon turn a handle and produce long, crackling sparks, snatched at the interruption.

“I must go up and see what’s happening!” he cried. “I’ll be back in a minute.”

He vanished up the steps. When he returned, Jeremy was still turning over the body of the rat with a thoughtful expression and placing it delicately to his nose for olfactory evidence. Trehanoc, who seemed to have begun to think that there was something shameful, if not highly suspicious, in the existence of the corpse, stood before him in an almost suppliant attitude, twisting his long fingers together, and shuffling his feet.

Maclan disregarded the high scientific deliberations. “I say,” he cried with the almost hysterical flippancy that sometimes denotes serious nerve-strain, “it’s frightfully exciting. The fighting is getting nearer, and somebody’s got a machine-gun trained down Whitechapel High Street. There’s nobody in sight here, but I’m certain there are people firing from the houses round about.”

“Oh, damn!” said Jeremy uneasily but absently, continuing to examine the rat.

“And, I say, Tre,” Maclan went on, “do you think this barn of yours would stand a bomb or two? It looks to me as if it would fall over if you pushed it.”

“I’m afraid it would,” Trehanoc admitted, looking as if he ought to apologize. “In fact, I’m always afraid that they’ll condemn it, but I can’t afford repairs.”

“Oh, hang all that!” Jeremy suddenly interjected. “This is extraordinarily interesting. Get the thing going, Trehanoc, and let’s have a look at your rays.”

“That’s right, Tre,” said Maclan. “We’re caught, so let’s make the best of it. Let’s try and occupy our minds as the civilians used to in the old air-raid days. Stick to the dead rat, Tre, and let politics alone.” He laughed — a laugh in which hysteria was now plainly perceptible — but Trehanoc, disregarding him, went into a corner and began fumbling with the switches. In a moment the vacuum-tube began to glow faintly, and Jeremy and Trehanoc bent over it together.

Suddenly a loud knocking at the front door echoed down the cellar steps. Trehanoc twitched his shoulders irritatingly, but otherwise did not move. A moment after it was repeated, and in addition there was a more menacing sound as though some one were trying to break the door in with a heavy instrument.

“You’d better go and see what it is, Augustus,” Jeremy murmured absorbedly. “It may be some one wanting to take shelter from the firing. Go on, and I’ll watch this thing.”

Trehanoc obediently but reluctantly went up the cellar steps, and Jeremy, with some idle, half-apprehending portion of his mind, heard him throw open the front door and heard the sound of angry voices coming through. But he remained absorbed in the vacuum-tube, until Maclan, who was standing at the foot of the steps, said in a piercing whisper:

“Here, Tuft, come here and listen!”

“Yes? What is it?” Jeremy replied vaguely, without changing his position.

“Come here quickly,” Maclan whispered in an urgent tone. Jeremy was aroused and went to the foot of the steps to listen. For a moment he could only hear voices speaking angrily, and then he distinguished Trehanoc’s voice shouting:

“You fools! I tell you there’s no one in the upper rooms. How could any one be firing from the windows?” There was a shot and a gurgling scream. Jeremy and Maclan turned to look at one another, and each saw the other’s face ghastly, distorted by shadows which the electric light in the cellar could not quite dispel.

“Good God!” screamed Maclan. “They’ve killed him!” He started wildly up the stairs. Jeremy, as he began to follow him, heard another shot, saw Maclan poised for a moment, arms up, on the edge of a step, and just had time to flatten himself against the wall before the body fell backwards. He ran down again into the cellar, and began looking about desperately for a weapon of some kind.

As he was doing so there was a cautious footstep on the stair. “Bombs!” he thought, and instinctively threw himself on the floor. The next moment the bomb landed, thrown well out in the middle of the cellar, and it seemed that a flying piece spun viciously through his hair. And then he saw the table which held the glowing vacuum-tube slowly tilting towards him and all the apparatus sliding to the floor, and at the same moment he became aware that the cellar-roof was descending on his head. He had time and wit enough to crawl under the other table before it fell. Darkness came with it.

Jeremy struggled for a moment against unconsciousness. Then something seemed to be going round and round, madly and erratically at first, finally settling into a regular motion of enormous speed. He was vaguely aware of the glowing vacuum-tube, and the dead rat, partly illuminated by it, close to his face; but he felt himself being borne away, he knew not whither. A sort of peace in that haste overtook his limbs and he slept.

NEXT WEEK: “The machine was sufficiently remarkable, and reminded him of nothing so much as of some which he had seen in the occupied territories of Germany at the end of the war. Its frame was exceedingly heavy, as were all the working parts which could be seen; and it was covered, not with enamel, but with a sort of coarse paint. The spokes of the wheels were half the size of a man’s little finger, and the rims were of thick wood, with springs in the place of tires.”

RADIUM AGE SCIENCE FICTION: “Radium Age” is HILOBROW’s name for the 1904–33 era, which saw the discovery of radioactivity, the revelation that matter itself is constantly in movement — a fitting metaphor for the first decades of the 20th century, during which old scientific, religious, political, and social certainties were shattered. This era also saw the publication of genre-shattering writing by Edgar Rice Burroughs, Sax Rohmer, E.E. “Doc” Smith, Jack London, Arthur Conan Doyle, Aldous Huxley, Olaf Stapledon, Karel Čapek, H.P. Lovecraft, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Yevgeny Zamyatin, Philip Gordon Wylie, and other pioneers of post-Verne/Wells, pre-Golden Age “science fiction.” More info here.

HILOBOOKS: The mission of HiLoBooks is to serialize novels on HiLobrow; and also, as of 2012, operating as an imprint of Richard Nash’s Cursor, to reissue Radium Age science fiction in beautiful new print editions. So far, we have published Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague, Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”), Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt, H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook, Edward Shanks’s The People of the Ruins, William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land, and J.D. Beresford’s Goslings. Forthcoming: E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man, Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage, and Muriel Jaeger’s The Man with Six Senses. For more information, visit the HiLoBooks homepage.

READ: Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague, serialized between January and April 2012; Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”), serialized between March and June 2012; Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt, serialized between April and July 2012; and H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook, serialized between March and August 2012.

ORIGINAL FICTION: HILOBROW has serialized three novels: James Parker’s The Ballad of Cocky The Fox (“a proof-of-concept that serialization can work on the Internet” — The Atlantic) and Karinne Keithley Syers’s Linda Linda Linda. We also publish original stories and comics.