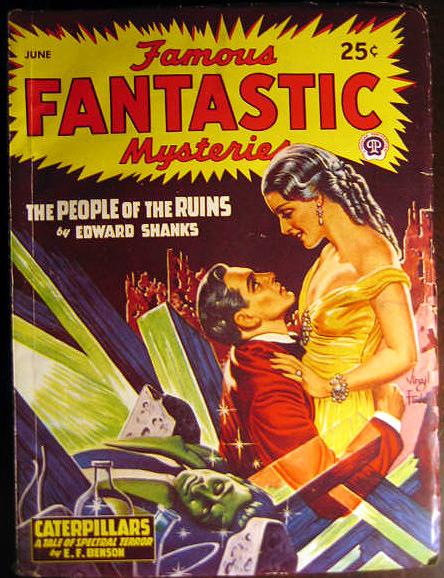

The People of the Ruins (1)

By:

May 24, 2012

HILOBROW is pleased to present the first installment of our serialization of Edward Shanks’ The People of the Ruins: A Story of the English Revolution and After. New installments will appear each Thursday for 16 weeks.

Trapped in a London laboratory during a worker uprising in 1924, ex-artillery officer and physics instructor Jeremy Tuft awakens 150 years later — in a neo-medieval society whose inhabitants have forgotten how to build or operate machinery. Not only have his fellow Londoners forgotten most of what humankind used to know, before civilization collapsed, but they don’t particularly care to re-learn any of it. Though he is at first disconcerted by the failure of his own era’s smug doctrine of Progress, Tuft eventually decides that post-civilized life is simpler, more peaceful. That is, until northern English and Welsh tribes threaten London — at which point he sets about reinventing weapons of mass destruction.

Shanks’ post-apocalyptic novel, a pessimistic satire on Wellsian techno-utopian novels, was first published in 1920. In October, HiLoBooks will publish a beautiful new edition of The People of the Ruins, with an introduction by Tom Hodgkinson.

SUBSCRIBE to HILOBROW’s serialized fiction via RSS.

ALL EXCERPTS: 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 |15 |16

TROUBLE

Mr. Jeremy Tuft became aware with a slight shock that he was lying in bed wide awake. He raised his head a little, stared around him, found something vaguely unfamiliar, and tried to go to sleep again. But sleep would not come. Though he felt dull and stupid, he was yet invincibly awake. His eyes opened again of themselves, and he stared round him once more. It was the subdued light, filtered through the curtains, that was strange; and as intelligence flowed back into his empty mind, he realized that this was because it was much stronger than it should have been at any time before eight o’clock. Thence to the conclusion that it was very likely later than eight o’clock was an easy step for his reviving faculties. Energy followed the returning intelligence, and he sat up suddenly, his head throbbing as he did so, and took his watch from the table beside him. It was, in fact, a quarter to ten.

Arising out of this discovery a stream of possibilities troubled the still somewhat confused processes of his mind. Either Mrs. Watkins for some unaccountable reason had failed to arrive, or else, contrary to his emphatic and often repeated instructions, she had been perfunctory in knocking at his door and had not stayed for an answer. In either case it was annoying; but Mrs. Watkins’ arrival at half-past seven was so fixed a point in the day, she was so regular, so trustworthy, and, moreover, life without her ministrations was so unthinkable that the first possibility seemed much the less possible of the two. When Jeremy had thus exhausted the field of speculation he rose and went out of his room to speak sharply to Mrs. Watkins. His intention of severity was a little belied by the genial grotesqueness of his short and rather broad figure in dressing-gown and pyjamas; but he hoped that he looked a disciplinarian.

Mrs. Watkins, however, was not there. The flat was silent and completely empty. The blinds were drawn over the sitting-room windows, and stirred faintly as he opened the door. He passed into the kitchen, but not hopefully, for as a rule his ear told him without mistake when the charwoman was to be found there. As he had expected, she was not there, nor yet in the bathroom. There was a quite uncanny silence everywhere, so strange and yet at the same time so reminiscent of something that eluded his memory, that Jeremy paused a moment, head lifted in air, trying to analyze its effect on him. He ascribed it at last to the obvious cause of Mrs. Watkins’ absence at this unusually late hour; and he went further into the bathroom, whence he could see, with a little craning of the neck, the clock on St. Andrew’s Church in Holborn. This last testimony confirmed that of his watch. He returned to the sitting-room, struggling half-consciously in his mind with a quite irrational feeling, for which he could not account, that it was a Sunday. He knew very well that it was a Tuesday —Tuesday, the 18th of April, in the year 1924.

When he came into the sitting-room he drew back the blinds and let in the full morning light, and by its aid he surveyed unfavorably his overcoat lying where he had thrown it the night before, coming in late from a party. He looked also with some disgust at the glass from which he had drunk a last unnecessary whisky and soda previous to going to bed. Then he paddled back wearily with bare feet to the narrow kitchen (a cupboard containing a gas-stove and a smaller cupboard), set a kettle on to boil, and began the always laborious process of bathing, shaving, and dressing. At the end he shirked making tea, or boiling an egg, and he sat down discontentedly to another whisky, in the same glass, and a piece of stale bread.

As he consumed this unsuitable meal he remembered his appointment for one o’clock that day, and hoped with a sudden devoutness that the ‘buses would be running after all. It was no joke to go from Holborn to Whitechapel High Street on foot. But a young and rather aggressive Socialist whom he had unwillingly met at that party had predicted with confidence a strike of ’busmen some time during the evening. Certainly Jeremy had had to walk all the way home from Chelsea, a thing he much disliked, but then perhaps by that time the ’buses had stopped running in the ordinary course… They did stop running, those Chelsea ’buses — a horrid place — at an ungodly early hour, he was not quite sure what. But then he was not quite sure at what time he had started home… he was not really sure of anything that had happened towards the end of the party. He remembered long, devastating arguments in the earlier part about Anarchism, Socialism, Syndicalism, Bolshevism, and some other doctrines, the names of which were formed on the same analogy, but which were too novel to him to be readily apprehended.

These discussions were mingled with more practical but equally windy disputes on the questions whether the railwaymen would come out, whether the miners were bluffing, what Bob Hart was going to do, and much more besides on the same level of interest. There had been also a youth with great superiority of manner, who seemed as tedious and irritating to the politicians as they were to Jeremy — a sort of super-bore who stated at intervals that the General Strike was a myth, but praised all and sundry for talking about it and threatening it. It had been — hadn’t it?— a studio party. At least, Jeremy had gone to it on that understanding; but the political push had rushed it somehow, and had bored everybody else to tears. Jeremy, who did not very much relish political argument, had applied himself to a kind of pleasure he could better understand. He now remembered little enough of those long, muddling disputations, punctuated by visits to the sideboard, but he knew that his head ached terribly. Aspirin tablets washed down with whisky would probably not be much good, but they would be better than nothing. He took some.

In the midst of these difficulties and discomforts he began obscurely to miss something; and at last it flashed on him that he had no morning paper — because there had been no Mrs. Watkins to bring it in with her and put it on his table. He realized at the same time that the morning paper would tell him whether he had to walk to Whitechapel High Street, and that it was worth a journey to the street door from his flat at the top of the building to know the worst. But when he had made the journey there was no paper. While he was reflecting on this disagreeable fact an envelope in the letter box caught his eye. It was addressed to him in a somewhat illiterate script, and appeared to have been delivered by hand, since it bore no stamp. When he opened it he found the following communication:

“DERE SIR,—Ime sorry to tell you I shal not be able to come in to-morro as we working womin have gone on stricke in simpathy with husbands and other working men the buses are al out and the railways and so are we dere Mr. Tuft I dont know Ime sure how you will get on without me but do youre best and dont forget today is the day for your clean underclose they are in the chest of draws there is a tin of sardins in the larder so no more at present from your truely.

“MRS. WATKINS.”

“Well, I’m damned…” said Mr. Tuft, staring at this touching epistle; and for a moment he was filled with annoyance by the recollection that he had not put on his clean othes. Presently, however, he trailed upstairs again; and when he had found the sardines in the larder the effort thus endured strengthened him for the task of making tea. Eventually he got ready a quite satisfactory breakfast, in the course of which his mind cleared to an exhausted and painful lucidity.

“That’s what it is!” he cried at last, thumping the table; and in his excitement, he let the last half sardine slide off his fork and on to the floor. He groped after it, wincing and starting up when his head throbbed too badly, retrieved the rather dusty fish, wiped it carefully with his napkin, and slowly ate it. The strange silence and the odd feeling that this was Sunday morning were at last explained. The printing works across the narrow street were empty, and through the grimy windows Jeremy could see the great machines standing idle. Below there were no carts, where usually they banged and clattered through the whole working day. The printers were out on strike. Very possibly everybody had struck; for surely nothing short of a national upheaval could have deterred the industrious Mrs. Watkins from her work.

He went to his window and threw it wide open to make a nearer inspection. The traffic which usually thronged the noisy little street, the carts and cars which stood outside the newspaper offices and printing works, were absent. A few of the tenement-dwellers lounged at their doors in such groups as were commonly seen only at night or on Saturday afternoons or Sundays. Jeremy felt a faint thrill go through him. This looked like being exciting. He had seen upheavals before, but never, even in the worst of them, had he seen this busy district in a state of idleness so Sabbatical. There had been ’bus strikes and tube strikes in 1918 and 1919, and since. The railwaymen and the miners had come out together for two days late in 1920, and had made a paralyzing impression. But throughout these affairs somehow printing had gone on, and newspapers had continued to be published, getting at each crisis, according to the temperaments of their proprietors, politer or more abusive towards the strikers. At the end of the previous year, 1923, when a very serious situation had arisen, and a collapse had been narrowly averted, there had been a distinct and arresting note of helpless panic in both politeness and abuse. During the last few days, while the present trouble was brewing, neither had much appeared in the papers, but only an exhibition of dithering fright.

But Jeremy had grown on the whole accustomed to it. He had ceased to believe in the coming of what some of the horrible people he had met at that studio referred to caressingly as the “Big Show.” The Government would always arrange things somehow. The wages of lecturers and investigators in physics (of whom he was one) never went up, because they never went on strike, and because it was unlikely that any one would care if they did. He had not been able to believe that a time would ever come when there would be no Government, no Paymaster-General, no Ministry of Pensions, to pay him his partial disability pension. But this morning unexpected events seemed much more probable. There was not much of the world to be perceived from his window looking down the street, but what there was smelt somehow remarkably like real trouble.

Jeremy Tuft was not unused to “trouble” of one sort and another. When the Great War began in 1914 he was a lecturer on physical science in one of the modern universities of Northern England. He had published a series of papers on the Viscosity of Liquids, which had gained him a European reputation — that is to say, it had been quoted with approval by two Germans and a Pole, while the conclusions had been appropriated without acknowledgment by a Norwegian — and he received a stipend of £300 per annum, to which he added a little by private coaching in his spare time. With what was left of his spare time he tried to make the liquids move faster or slower or in some other direction — in view of his ultimate destiny it matters very little which — and at all events to gather such evidence as would blow the Norwegian, for whom he had conceived an unreasonable hatred, quite out of the water.

War called him from these pursuits. He did not stand upon his scientific status or attainments; but concluding that the country wanted MEN to set an example, he hastened to set an example by applying for a commission in the artillery, which, after some difficulty, he obtained. When the first excitement and muddle had been cleared away, so he supposed, no doubt the specialists would be sorted out and set to do the jobs for which they were best fitted. He was a naturally modest man; but he could think of two or three jobs for which he was very well fitted indeed.

He passed through Woolwich in a breathless rush, and learnt to ride even more breathlessly. As the day for departure overseas drew near he congratulated himself a little that the inevitable sorting-out seemed to be postponed. He would get a few weeks more of this invaluable experience in a sphere which was completely unfamiliar to him; he would perhaps even see some of the fighting which he had never really expected. When, five days after his arrival in the Salient with the battery of sixty-pounders to which he was attached, one of the guns blew up with a premature explosion and drenched him in blood not his own, he felt that his experience was reasonably complete, and began to look forward to the still deferred sorting-out. Unfortunately, it continued to be deferred; but after a little while Jeremy settled down with the battery, and rose in it to the rank of captain.

His companions described him as the most consistent and richly eloquent grumbler on the British front; and he filled in his spare time by poking round little shops in Béthune and such towns, and picking up old, unconsidered engravings and some rather good lace. In the early part of 1918, his horse, in a set-to with a traction-engine, performed the operation of sorting-out which the authorities had so long neglected; and Jeremy, when his dislocated knee was somewhat recovered, parted forever from the intelligent animal, and went to use his special attainments as a bottle-washer in the office of Divisional Headquarters. The armistice came; and he was released from the army after difficulties much exceeding those which he had encountered in entering it.

In April, 1922, he was again a lecturer in physics, this time at a newly-instituted college in London, receiving a stipend of £350 per annum, to which he was luckily able to add a partial disability pension of £20. In his spare moments he pursued the Viscosity of Liquids with a movement less lively than their own; but he had forgotten the Norwegian’s name. He lived alone, not too uncomfortably, in his little flat in Holborn, a short distance from the building where it was his duty to explain to young men who sometimes, and young women who rarely, understood him, the difference between mass and weight, and other such interesting points. He was tended daily by the careful Mrs. Watkins, and he had a number of friends, mostly artists, whose tendency to live in Chelsea or in Camden Town he heartily deplored.

On this morning of April, 1924, the first day of the Great Strike or the Big Show, Jeremy set out at a few moments after eleven to keep his appointment with a friend who lived in a place no less inconvenient than the Whitechapel High Street. The streets were, as they had seemed from his windows, even emptier and quieter than on a Sunday, and most of the shops were closed. But there was, on the whole, a feeling of electricity in the air that Jeremy had never associated with that day. It was when he came into Fetter Lane and saw a patrol of troops lying on the grass outside the Record Office that he first found something concrete to justify this feeling.

“There is going to be trouble, then,” he muttered to himself, admitting it with reluctance, as he walked on steadily into Fleet Street; and there his apprehensions were again confirmed. A string of lorries came rapidly down the empty roadway, past him from the West, and they were crowded with troops. Guards, he thought — carrying machine-guns in the first lorry.

Jeremy paused for a moment, staring after them, and then as he turned to go on he saw a small special constable standing as inconspicuously as possible in the door of a shop, swinging nervously the truncheon at his wrist. His uniform looked a little dusty and unkept, and there was an obvious moth-hole on one side of the cap. His whole appearance was that of a man desperately imploring Providence not to let anything happen.

“That man’s face is simply asking for a riot,” Jeremy grunted to himself; and he said aloud, “Perhaps you can tell me what it’s all about?”

The special constable started suspiciously. But seeing that Jeremy was comparatively well-dressed, and seemed to be a member of what in those days was beginning to be known as the P.B.M.C.* he was reassured. Jeremy’s air of clumsy geniality and self-confidence was, moreover, far removed from the sinister aspect of the traditional Bolshevist. “I don’t know really,” he said in a complaining voice, “it’s so difficult to find out with no newspapers or anything. All I do know for certain is that we were called out last night, and some say one thing and some another.”

[ * A phrase which gained currency in 1919 or earlier, and which was formed on the analogy of P.B.I., used, to describe themselves, by the infantry in the Great War.]

“How long have you been on duty?” Jeremy asked.

“Only an hour,” the special constable replied. “I slept at the station all night on the floor.”

“Like old times in billets, what?” Jeremy remarked pleasantly, observing a silver badge on the man’s right lapel.

“No… Oh, no… I wasn’t ever in the army really. They invalided me out after three days. I’m not strong, you know —I’m not fit for this sort of thing. And we didn’t get any proper sleep.”

“Why not?”

“We were afraid we might be attacked,” said the special constable darkly. “Nearly all the police are out. There was only an inspector and a sergeant at the station besides us.”

“Well, who else is out?” Jeremy asked.

“The railwaymen came out yesterday, and the busmen last night. All the miners are out now. And the printers, too. They say the electrical men are out, too, but I don’t know about that.”

“Looks like almighty smash, don’t it?” Jeremy commented. “Where are all those troops going?”

“I don’t know,” said the special constable. “Nobody really knows anything for certain.”

“Cheerful business,” Jeremy grumbled, mostly to himself. “And how the devil am I going to get to Whitechapel High Street, I wonder?”

“To Whitechapel High Street?” the special constable cried. “Down in the East End? Oh, don’t go down there! It’ll be frightfully dangerous there!”

“That be damned,” said Jeremy. “I can’t say you look as though you were feeling particularly safe yourself, do you?” And with a wave of his hand he passed down Fleet Street in an easterly direction.

It was only a few hundred yards farther on that he received his first personal shock of the day. As he came to Ludgate Circus he heard an empty lorry, driven at a furious rate, bumping and clanging down the street behind him. At the same time a large gray staff car, packed with red-tabbed officers, shot into the Circus out of Farrington Street, making for Black-friars Bridge. His heart was for a moment in his mouth, but the driver of the lorry pulled up abruptly and let the car go by, stopping his own engine as he did so. Jeremy saw him descend, swearing softly, to crank up again; and the sight of the empty vehicle revived in him glad memories of the French and Flemish roads. He therefore stepped into the street, and said with a confidence that returned to him naturally from earlier years:

“Look here, my lad, if you’re going east, you might give me a bit of a lift.”

The soldier had got his engine going again, and rose from the starting handle with a flushed and frowning face.

“’Oo are you talkin’ to?” he asked sullenly. “’Oo the ’ell do you think this lorry belongs to, eh? Think it belongs to you?” And as Jeremy was too taken aback to answer, he continued: “This lorry belongs to the Workmen’s and Soldiers’ Council of Southwark, that’s ’oo it belongs to.” He climbed slowly back into his seat, and, as he slipped the clutch in, leant outwards to Jeremy and exclaimed in a particularly emphatic and vicious tone, “Dirty boorjwar!” The machine leapt forward, swept round the Circus, and disappeared over the bridge.

Jeremy, a little perturbed by this incident, pursued his journey, unconsciously grasping his heavy cane somewhat tighter, and glancing almost nervously down every side street or alley he passed, hardly knowing for what he looked. His notion of the way by foot to Whitechapel High Street was not very clear, but he knew more or less the way to Liverpool Street, and he supposed that by going thither he would be following the proper line. He therefore trudged up Ludgate Hill and along Cheapside, cursing the Revolution and all extremists from the bottom of his heart. The lorry driver’s parting shot still rankled in his mind. He felt that it was extremely unjust to accuse him of being a member of the bourgeoisie, and he was quite ready to exchange all his vested interests in anything whatever against a seat in a ’bus.

Close to Liverpool Street Station he came out of deserted and silent streets, whose silence and emptiness had begun to have an effect on his nerves, into a scene of activity and animation. A string of five lorries, driven by soldiers, but loaded with something hidden under tarpaulins instead of troops, was drawn up by the curb, while a large and growing crowd blocked its further progress. The crowd was held together apparently by an orator mounted on a broken chair, who was lashing himself into a fury which he found difficult to communicate to his audience. Jeremy pushed forward as unobtrusively as he could, but eventually found himself stayed, close to the foremost lorry, on the skirts of the crowd. The orator, not far off, was working himself into ever wilder and wilder passions.

“The hour has come,” he was saying. “All over the country our brothers have risen —”

“And I and my brothers,” Jeremy murmured to himself, “are going to get the dirty end of the stick.”

But as he looked about him and examined the crowd in which he was involved, he found some difficulty in connecting it with the fiery phrases of the speaker or with the impending Revolution which, until this moment, he had really been beginning to dread. Now a sudden wave of relief passed over his mind. These honest, blunt, good-natured people had expressed the subtle influence of the day, which he himself had felt, by putting on their Sunday clothes. They were not meditating bloodshed or the overthrow of the State. But for a certain seriousness and determination in their faces and voices one might have thought that they were making holiday in an unpremeditated and rather eccentric manner. Their seriousness was not that of men forming desperate resolves. It was that of men who, having entered into an argument, intend to argue it out. They believed in argument, in the power of reason, and the voting force of majorities. They applauded the speaker, but not when he became blood-thirsty; and time and time again he lost touch with them in his violence. At the most frenzied point of the oration a thick-set man, with a startling orange handkerchief round his neck, turned to Jeremy and said disgustedly:

“Listen to ’im jowin’! Sheeny, that’s what he is, no more than a —— Sheeny.” Jeremy was neither a politician nor a sociologist. He did not weigh a previous diagnosis against this fresh evidence and come to a more cheerful conclusion; but he breathed rather more freely and relaxed his grip on his cane. He was not disturbed by the confused and various clamor which came from the crowd and in which there was a good admixture of laughter.

Just at this moment he saw on the lorry by which he had halted a face that was familiar to him. He looked again more closely, and recognized Scott —Scott who had been in the Divisional Office, Scott who had panicked so wildly in the 1918 retreat, though God knew he had taken a long enough start, Scott who had nearly landed him in a row over that girl in the estaminet at Bailleul, just after the armistice. And Scott, who never knew that he was disliked — a characteristic of his kind!— was eagerly beckoning to him.

He slid quietly through the fringe of the crowd and stood by the driving-seat of the lorry. Scott leant down and shook him by the hand warmly, speaking in a whisper:

“Tuft, old man,” he said effusively, “I often wondered what had become of you. What a piece of luck meeting you here!”

“I could think of better places to meet in,” Jeremy answered drily. He was determined not to encourage Scott; he knew very well that something damned awkward would most likely come of it. “This looks to me like a hold-up. What have you got in the lorries?”

“Sh!” Scott murmured with a scared look. “It’s bombs for the troops at Liverpool Street, but it’d be all up with us if the crowd knew that. No — why I said it was lucky was because I thought you might help me to get through.”

“I? How could I?” Jeremy asked defensively.

“Well, I don’t know…. I thought you might have some influence with them, persuade them that there’s nothing particular in the lorries, or…”

Jeremy favored him with a stare of bewildered dislike. “Why on earth should I have any influence with them?” he enquired.

“Don’t be sick with me, old man… I only thought you used to have some damned queer opinions, you know; used to be a sort of Bolshevist yourself… I thought you might know how to speak to them.” Scott, of course, always had thought that any man whose opinions he could not understand was a sort of Bolshevist. Jeremy shirked the task of explanation and contented himself with calling his old comrade-in-arms an ass.

“And, anyway,” he went on, “I’ll tell you one thing. There isn’t likely to be any revolution hereabouts, unless you make it yourself. What are you stopping for? Did they make you stop?”

“Not exactly… don’t you see, the General said….”

Jeremy heaved a groan. He had heard that phrase on Scott’s lips before, and it was generally a sign that the nadir of his incapacity had been reached. Heaven help the Social Order if it depended on Scott’s fidelity to what the General had said! But the voice above him maundered on, betraying helplessness in every syllable. The General had said that the bombs were at all costs to reach the troops at Liverpool Street. He had also said that on no account must the nature of the convoy be betrayed; and on no account must Scott risk any encounter with a mob. And the mob had not really stopped the convoy. They had just shown no alacrity in making room for it, and Scott had thought that by pushing on he would perhaps be risking an encounter. Now, however, he thought that by remaining where he was might be exciting curiosity.

Jeremy looked at him coolly, and spoke in a tone of restrained sorrow. “Scott,” he said, “it takes more than jabberers like this chap here to make a revolution. They want a few damned fools like you to help them. I’m going on before the trouble begins.” And he drew back from the lorry and began to look about for a place where the crowd might be a little sparser. The orator on the broken chair had now been replaced by another, an Englishman, of the serious type, one of those working-men whose passion it is to instruct their fellows and who preach political reform with the earnestness and sobriety of the early evangelical missionaries. He was speaking in a quiet, intense tone, without rant or excitement, and the crowd was listening to him in something of his own spirit. Occasionally, when he paused on a telling sentence, there were low rumbling murmurs of assent or of sympathetic comment.

“No, but look here —” came from the lorry after Jeremy in an agonized whisper. But he saw his opportunity, and did not look back until he was on the other side of the crowd round the speaker. He went on rapidly eastwards past the station, his mood of relief already replaced by an ominous mood of doubt. Once or twice, until the turn of the street hid them, he glanced apprehensively over his shoulders at the crowd and the string of motionless lorries.

NEXT WEEK: “‘Well, first of all, my hand went queer. It was a sort of dead, numb feeling, spreading into the arm above the wrist, and I was scared, I can tell you. I was almost certain that these were new rays, and I hadn’t the least notion what effect they might have on living tissue. The numbness kept on all day, with a sort of tingling in the finger-tips, and I went to bed in a bit of a panic. And when I woke, the radium burn had quite gone, leaving a little scar behind, and the cut had begun to heal. It was very nearly healed!'”

RADIUM AGE SCIENCE FICTION: “Radium Age” is HILOBROW’s name for the 1904–33 era, which saw the discovery of radioactivity, the revelation that matter itself is constantly in movement — a fitting metaphor for the first decades of the 20th century, during which old scientific, religious, political, and social certainties were shattered. This era also saw the publication of genre-shattering writing by Edgar Rice Burroughs, Sax Rohmer, E.E. “Doc” Smith, Jack London, Arthur Conan Doyle, Aldous Huxley, Olaf Stapledon, Karel Čapek, H.P. Lovecraft, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Yevgeny Zamyatin, Philip Gordon Wylie, and other pioneers of post-Verne/Wells, pre-Golden Age “science fiction.” More info here.

HILOBOOKS: The mission of HiLoBooks is to serialize novels on HiLobrow; and also, as of 2012, operating as an imprint of Richard Nash’s Cursor, to reissue Radium Age science fiction in beautiful new print editions. So far, we have published Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague, Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”), Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt, H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook, Edward Shanks’s The People of the Ruins, William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land, and J.D. Beresford’s Goslings. Forthcoming: E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man, Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage, and Muriel Jaeger’s The Man with Six Senses. For more information, visit the HiLoBooks homepage.

READ: Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague, serialized between January and April 2012; Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”), serialized between March and June 2012; Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt, serialized between April and July 2012; and H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook, serialized between March and August 2012.

ORIGINAL FICTION: HILOBROW has serialized three novels: James Parker’s The Ballad of Cocky The Fox (“a proof-of-concept that serialization can work on the Internet” — The Atlantic) and Karinne Keithley Syers’s Linda Linda Linda. We also publish original stories and comics.