With the Night Mail (10)

By:

May 23, 2012

HILOBROW is pleased to present the tenth installment of our serialization of Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and his follow-up story, “As Easy as A.B.C.”). New installments will appear each Wednesday for 12 weeks.

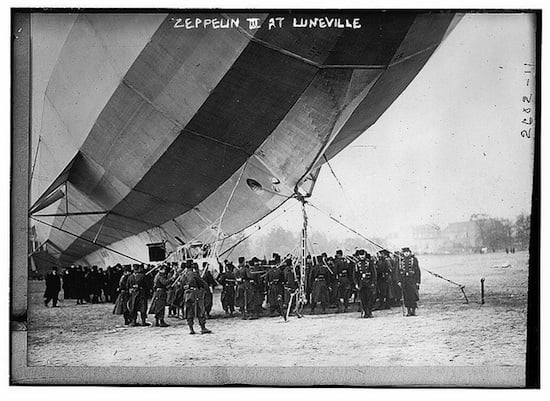

With the Night Mail follows the exploits of an intercontinental mail dirigible battling the perfect storm. Between London and Quebec we learn that a planet-wide Aerial Board of Control (A.B.C.) now enforces a technocratic system of command and control not only in the skies but in world affairs, too. A follow-up story, “As Easy As A.B.C.,” recounts what happens when agitators in Chicago demand a return of democracy: The A.B.C. sends zeppelins armed with sound weapons to subdue not the agitators, but a mob who would destroy them! With the Night Mail is set in 2000, and it first appeared in 1905; 2012 marks the centennial of the first publication of “As Easy As A.B.C.”

In June, HiLoBooks will publish a beautiful new edition of With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”), checked against the 1909 first published edition (Doubleday), with an Introduction by science fiction author Matthew De Abaitua, and an Afterword by science fiction author Bruce Sterling. SUPPLIES ARE LIMITED! CLICK HERE TO ORDER YOUR COPY.

SUBSCRIBE to HILOBROW’s serialized fiction via RSS.

LAST WEEK: “In the utter hush that followed the growling spark after Arnott had linked up his Service Communicator with the invisible Fleet, we heard MacDonough’s Song from the city beneath us grow fainter as we rose to position. Then I clapped my hand before my mask lenses, for it was as though the floor of Heaven had been riddled and all the inconceivable blaze of suns in the making was poured through the manholes.”

ALL EXCERPTS: 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12

Chicago North landing-tower was unlighted, and Arnott worked his ship into the clips by her own lights. As soon as these broke out we heard groanings of horror and appeal from many people below.

‘All right,’ shouted Arnott into the darkness. ‘We aren’t beginning again!’ We descended by the stairs, to find ourselves knee deep in a grovelling crowd, some crying that they were blind, others beseeching us not to make any more noises, but the greater part writhing face downward, their hands or their caps before their eyes.

It was Pirolo who came to our rescue. He climbed the side of a surfacing-machine, and there, gesticulating as though they could see, made oration to those afflicted people of Illinois.

‘You stchewpids!’ he began. ‘There is nothing to fuss for. Of course, your eyes will smart and be red to-morrow. You will look as if you and your wives had drunk too much, but in a little while you will see again as well as before. I tell you this, and I—I am Pirolo. Victor Pirolo!’

The crowd with one accord shuddered, for many legends attach to Victor Pirolo of Foggia, deep in the secrets of God.

‘Pirolo?’ An unsteady voice lifted itself. ‘Then tell us was there anything except light in those lights of yours just now?’

The question was repeated from every corner of the darkness.

Pirolo laughed.

‘No!’ he thundered. (Why have small men such large voices?) ‘I give you my word and the Board’s word that there was nothing except light — just light! You stchewpids! Your birth-rate is too low already as it is. Some day I must invent something to send it up, but send it down — never!’

‘Is that true?—We thought — somebody said —’

One could feel the tension relax all round.

‘You too big fools,’ Pirolo cried. ‘You could have sent us a call and we would have told you.’

‘Send you a call!’ a deep voice shouted. ‘I wish you had been at our end of the wire.’

‘I’m glad I wasn’t,’ said De Forest. ‘It was bad enough from behind the lamps. Never mind! It’s over now. Is there any one here I can talk business with? I’m De Forest — for the Board.’

‘You might begin with me, for one —I’m Mayor,’ the bass voice replied.

A big man rose unsteadily from the street, and staggered towards us where we sat on the broad turf-edging, in front of the garden fences.

‘I ought to be the first on my feet. Am I?’ said he.

‘Yes,’ said De Forest, and steadied him as he dropped down beside us.

‘Hello, Andy. Is that you?’ a voice called.

‘Excuse me,’ said the Mayor; ‘that sounds like my Chief of Police, Bluthner!’

‘Bluthner it is; and here’s Mulligan and Keefe — on their feet.’

‘Bring ’em up please, Blut. We’re supposed to be the Four in charge of this hamlet. What we says, goes. And, De Forest, what do you say?’

‘Nothing — yet,’ De Forest answered, as we made room for the panting, reeling men. ‘You’ve cut out of system. Well?’

‘Tell the steward to send down drinks, please,’ Arnott whispered to an orderly at his side.

‘Good!’ said the Mayor, smacking his dry lips. ‘Now I suppose we can take it, De Forest, that henceforward the Board will administer us direct?’

‘Not if the Board can avoid it,’ De Forest laughed. ‘The A.B.C. is responsible for the planetary traffic only.’

‘And all that that implies.’ The Big Four who ran Chicago chanted their Magna Charta like children at school.

‘Well, get on,’ said De Forest wearily. ‘What is your silly trouble anyway?’

‘Too much dam’ Democracy,’ said the Mayor, laying his hand on De Forest’s knee.

‘So? I thought Illinois had had her dose of that.’

‘She has. That’s why. Blut, what did you do with our prisoners last night?’

‘Locked ’em in the water-tower to prevent the women killing ’em,’ the Chief of Police replied. ‘I’m too blind to move just yet, but —’

‘Arnott, send some of your people, please, and fetch ’em along,’ said De Forest.

‘They’re triple-circuited,’ the Mayor called. ‘You’ll have to blow out three fuses.’ He turned to De Forest, his large outline just visible in the paling darkness. ‘I hate to throw any more work on the Board. I’m an administrator myself, but we’ve had a little fuss with our Serviles. What? In a big city there’s bound to be a few men and women who can’t live without listening to themselves, and who prefer drinking out of pipes they don’t own both ends of. They inhabit flats and hotels all the year round. They say it saves ’em trouble. Anyway, it gives ’em more time to make trouble for their neighbours. We call ’em Serviles locally. And they are apt to be tuberculous.’

‘Just so!’ said the man called Mulligan. ‘Transportation is Civilisation. Democracy is Disease. I’ve proved it by the blood-test, every time.’

‘Mulligan’s our Health Officer, and a one-idea man,’ said the Mayor, laughing. ‘But it’s true that most Serviles haven’t much control. They will talk; and when people take to talking as a business, anything may arrive — mayn’t it, De Forest?’

‘Anything — except the facts of the case,’ said De Forest, laughing.

‘I’ll give you those in a minute,’ said the Mayor. ‘Our Serviles got to talking — first in their houses and then on the streets, telling men and women how to manage their own affairs. (You can’t teach a Servile not to finger his neighbour’s soul.) That’s invasion of privacy, of course, but in Chicago we’ll suffer anything sooner than make crowds. Nobody took much notice, and so I let ’em alone. My fault! I was warned there would be trouble, but there hasn’t been a crowd or murder in Illinois for nineteen years.’

‘Twenty-two,’ said his Chief of Police.

‘Likely. Anyway, we’d forgot such things. So, from talking in the houses and on the streets, our Serviles go to calling a meeting at the Old Market yonder.’ He nodded across the square where the wrecked buildings heaved up grey in the dawn-glimmer behind the square-cased statue of The Negro in Flames. ‘There’s nothing to prevent anyone calling meetings except that it’s against human nature to stand in a crowd, besides being bad for the health. I ought to have known by the way our men and women attended that first meeting that trouble was brewing. There were as many as a thousand in the market-place, touching each other. Touching! Then the Serviles turned in all tongue-switches and talked, and we —’

‘What did they talk about?’ said Takahira.

‘First, how badly things were managed in the city. That pleased us Four — we were on the platform — because we hoped to catch one or two good men for City work. You know how rare executive capacity is. Even if we didn’t it’s — it’s refreshing to find any one interested enough in our job to damn our eyes. You don’t know what it means to work, year in, year out, without a spark of difference with a living soul.’

‘Oh, don’t we!’ said De Forest. ‘There are times on the Board when we’d give our positions if any one would kick us out and take hold of things themselves.’

‘But they won’t,’ said the Mayor ruefully. ‘I assure you, sir, we Four have done things in Chicago, in the hope of rousing people, that would have discredited Nero. But what do they say? “Very good, Andy. Have it your own way. Anything’s better than a crowd. I’ll go back to my land.” You can’t do anything with folk who can go where they please, and don’t want anything on God’s earth except their own way. There isn’t a kick or a kicker left on the Planet.’

‘Then I suppose that little shed yonder fell down by itself?’ said De Forest. We could see the bare and still smoking ruins, and hear the slag-pools crackle as they hardened and set.

‘Oh, that’s only amusement. Tell you later. As I was saying, our Serviles held the meeting, and pretty soon we had to ground-circuit the platform to save ’em from being killed. And that didn’t make our people any more pacific.’

‘How d’you mean?’ I ventured to ask.

‘If you’ve ever been ground-circuited,’ said the Mayor, ‘you’ll know it don’t improve any man’s temper to be held up straining against nothing. No, sir! Eight or nine hundred folk kept pawing and buzzing like flies in treacle for two hours, while a pack of perfectly safe Serviles invades their mental and spiritual privacy, may be amusing to watch, but they are not pleasant to handle afterwards.’

Pirolo chuckled.

‘Our folk own themselves. They were of opinion things were going too far and too fiery. I warned the Serviles; but they’re born house-dwellers. Unless a fact hits ’em on the head, they cannot see it. Would you believe me, they went on to talk of what they called “popular government”? They did! They wanted us to go back to the old Voodoo-business of voting with papers and wooden boxes, and word-drunk people and printed formulas, and news-sheets! They said they practised it among themselves about what they’d have to eat in their flats and hotels. Yes, sir! They stood up behind Bluthner’s doubled ground-circuits, and they said that, in this present year of grace, to self-owning men and women, on that very spot! Then they finished’— he lowered his voice cautiously —’by talking about “The People.” And then Bluthner he had to sit up all night in charge of the circuits because he couldn’t trust his men to keep ’em shut.’

‘It was trying ’em too high,’ the Chief of Police broke in. ‘But we couldn’t hold the crowd ground-circuited for ever. I gathered in all the Serviles on charge of crowd-making, and put ’em in the water-tower, and then I let things cut loose. I had to! The District lit like a sparked gas-tank!’

‘The news was out over seven degrees of country,’ the Mayor continued; ‘and when once it’s a question of invasion of privacy, good-bye to right and reason in Illinois! They began turning out traffic-lights and locking up landing-towers on Thursday night. Friday, they stopped all traffic and asked for the Board to take over. Then they wanted to clean Chicago off the side of the Lake and rebuild elsewhere — just for a souvenir of “The People” that the Serviles talked about. I suggested that they should slag the Old Market where the meeting was held, while I turned in a call to you all on the Board. That kept ’em quiet till you came along. And — and now you can take hold of the situation.’

‘Any chance of their quieting down?’ De Forest asked.

‘You can try,’ said the Mayor.

De Forest raised his voice in the face of the reviving crowd that had edged in towards us. Day was come.

‘Don’t you think this business can be arranged?’ he began. But there was a roar of angry voices:

‘We’ve finished with Crowds! We aren’t going back to the Old Days! Take us over! Take the Serviles away! Administer direct or we’ll kill ’em! Down with The People!’

An attempt was made to begin “MacDonough’s Song.” It got no further than the first line, for the Victor Pirolo sent down a warning drone on one stopped horn. A wrecked side-wall of the Old Market tottered and fell inwards on the slag-pools. None spoke or moved till the last of the dust had settled down again, turning the steel case of Salati’s Statue ashy grey.

‘You see you’ll just have to take us over’, the Mayor whispered.

De Forest shrugged his shoulders.

‘You talk as if executive capacity could be snatched out of the air like so much horse-power. Can’t you manage yourselves on any terms?’ he said.

‘We can, if you say so. It will only cost those few lives to begin with.’

The Mayor pointed across the square, where Arnott’s men guided a stumbling group of ten or twelve men and women to the lake front and halted them under the Statue.

‘Now I think,’ said Takahira under his breath, ‘there will be trouble.’

NEXT WEEK: “It appeared that our Planet lay sunk in slavery beneath the heel of the Aerial Board of Control. The orator urged us to arise in our might, burst our prison doors and break our fetters (all his metaphors, by the way, were of the most medieval). Next he demanded that every matter of daily life, including most of the physical functions, should be submitted for decision at any time of the week, month, or year to, I gathered, anybody who happened to be passing by or residing within a certain radius, and that everybody should forthwith abandon his concerns to settle the matter, first by crowd-making, next by talking to the crowds made, and lastly by describing crosses on pieces of paper, which rubbish should later be counted with certain mystic ceremonies and oaths.”

RADIUM AGE SCIENCE FICTION: “Radium Age” is HILOBROW’s name for the 1904–33 era, which saw the discovery of radioactivity, the revelation that matter itself is constantly in movement — a fitting metaphor for the first decades of the 20th century, during which old scientific, religious, political, and social certainties were shattered. This era also saw the publication of genre-shattering writing by Edgar Rice Burroughs, Sax Rohmer, E.E. “Doc” Smith, Jack London, Arthur Conan Doyle, Aldous Huxley, Olaf Stapledon, Karel Čapek, H.P. Lovecraft, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Yevgeny Zamyatin, Philip Gordon Wylie, and other pioneers of post-Verne/Wells, pre-Golden Age “science fiction.” More info here.

HILOBOOKS: The mission of HiLoBooks is to serialize novels on HiLobrow; and also, as of 2012, operating as an imprint of Richard Nash’s Cursor, to reissue Radium Age science fiction in beautiful new print editions. So far, we have published Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague, Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”), Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt, H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook, Edward Shanks’s The People of the Ruins, William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land, and J.D. Beresford’s Goslings. Forthcoming: E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man, Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage, and Muriel Jaeger’s The Man with Six Senses. For more information, visit the HiLoBooks homepage.

READ: You are reading Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail and “As Easy As A.B.C.” Also read our serialization of: Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague | H. Rider Haggard’s When The World Shook

ORIGINAL FICTION: HILOBROW has serialized three novels: James Parker’s The Ballad of Cocky The Fox (“a proof-of-concept that serialization can work on the Internet” — The Atlantic) and Karinne Keithley Syers’s Linda Linda Linda. We also publish original stories and comics.