(Amateur) Magical Thinking

By:

April 25, 2012

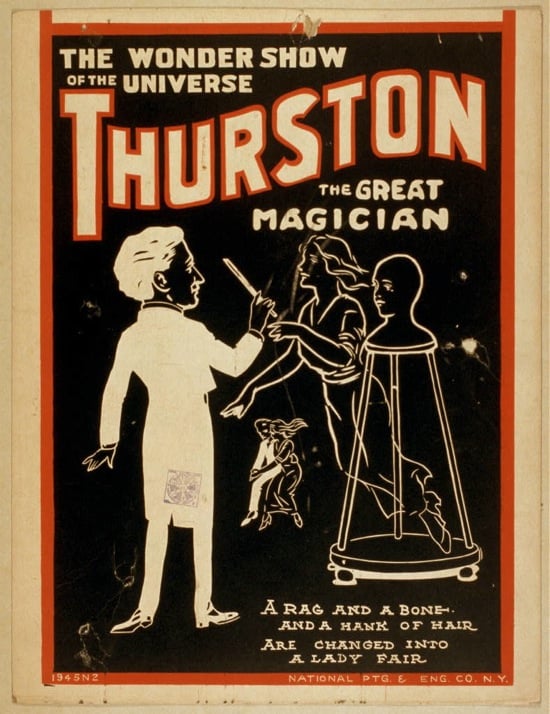

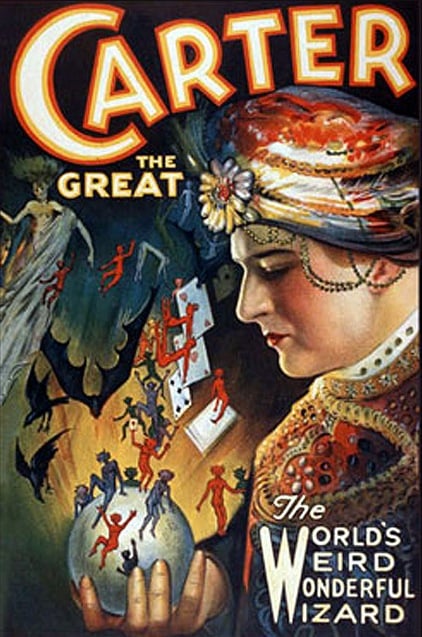

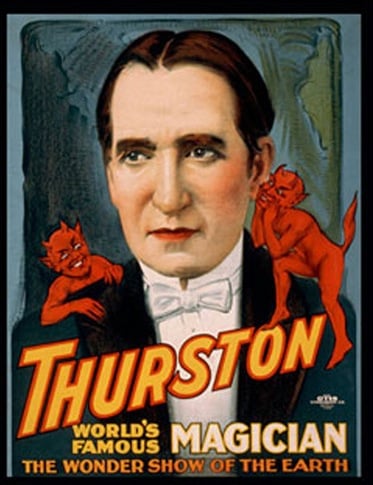

At the turn of the twentieth century, a newspaper observed that “The ‘Dabbler in Black Art,’ the ‘Famous Prestidigitateur,’ the ‘Marvellous Illusionist,’ the ‘Modern Wizard,’ as he fondly and variously styles himself, has in the past couple of seasons been reaping a fat financial harvest.” Another newspaper article proclaimed that “The American public loves to be mystified. This is proved by the large audiences magicians and illusionists succeed in getting together.” The overwhelming success of the magical profession was generally viewed as merely symptomatic of a vague American tendency to delight in recreational confusion. But magicians knew better than to attribute the explosion of demand for modern enchantment to anything so vague.

Although the source of magic’s allure remained somewhat mystifying even to the mystifiers themselves, they at least began to understand the extent of its penetration into the American psyche — specifically, the American male psyche. An 1897 biography of the famous magician Herrmann the Great said that “Not only boys, but men, and not only men, but great kings, emperors, philosophers, doctors and savants, have been mystified by the magician, and have showered upon him fame, fortune, and favor, and all for the love of mystery – mystery made so much more mysterious by the exaggerations of the narrator.” It was the performance that entranced the viewer, yes; but more than that, it was the performer and his eerie power to mesmerize and control his audience.

The driving force behind the magical craze was not a polite and appreciative general public, but a throng of fanatically ambitious males. Herrmann’s biography noted that the successful magician at the turn of the twentieth century was “applauded for his deftness, for his ingenuity, for his scientific attainments and his general cleverness, and he becomes famous just as the successful physician, the able lawyer, the brilliant writer, the clear statesman, the bright inventor, and all others who attain high places in any respectable and helpful calling.” The magician’s apparent cleverness and ingenuity – absolute prerequisites for success in any realm of male achievement – were what left his ambitious male audience starstruck and wanting more.

As demand for magicians’ acts increased, fueled by the attentions of these spellbound men, the diffuse coterie of isolated magicians began to realize that they might benefit from commiserating and exchanging knowledge with other like-minded people. However, since the magicians were linked not by locality but by an eccentric and highly individual profession, a traditional club complete with meetings and refreshments would have been an ineffective initial organizing device. Instead, a niche publication emerged onto the scene. Titled THE SPHINX: A MONTHLY ILLUSTRATED MAGAZINE DEVOTED EXCLUSIVELY TO MAGIC AND MAGICIANS, it served as a structuring mechanism for the burgeoning ranks of magicians. It was the de facto clearinghouse for all information regarding magicians; in effect, it created the magical community. This structure, in organizing professionals, also built the bodies of knowledge, resources, and connections necessary to attract and absorb what turned out to be the most lucrative group of all to the magical industry: the wealthy, would-be amateurs for whom magic was a fantasy hobby.

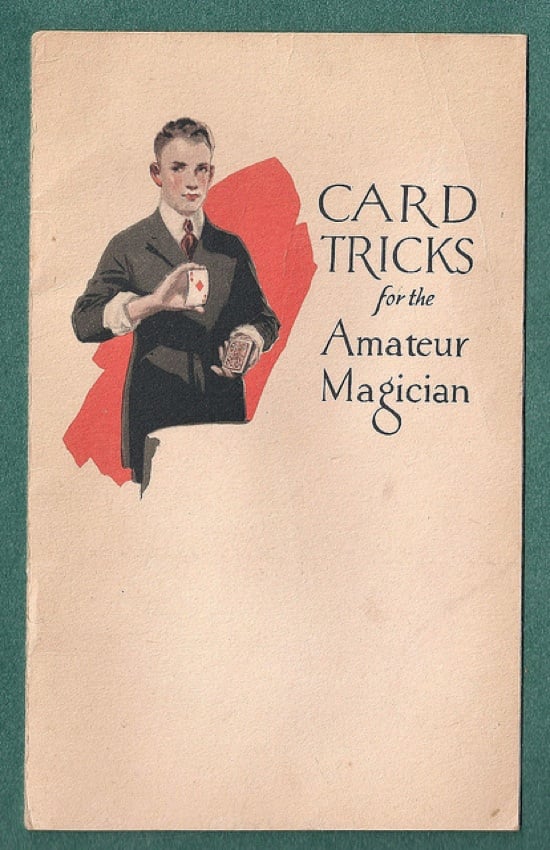

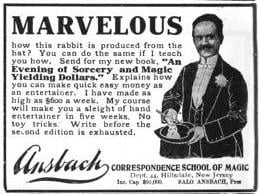

Amateur magicians poured their energy – and money – into this fantasy hobby because it offered them everything their humdrum careers did not: novelty, power, and the instructions for success. The democratization of magical knowledge through THE SPHINX made parlor magic an even more popular pursuit for the particularly industrious man. In place of a secret society, it created a society of secrets.

In a 1904 issue of THE SPHINX, an opinion article on magic’s rise as a pastime boasted that “A man may be clumsy and unfinished in all of his tricks, but to his admiring friends he is only perfection,” continuing that “It is so different from the usual routine of piano playing and singing that the novelty is hailed with acclamations of joy. The performer is immediately the lion of the hour and is the first to receive an invitation to another party.” Magic as a pastime was promoted as just another form of self-improvement, appealing directly to the specifically ambitious, specifically male admirers of the professional magicians themselves. The opinion article then went on to observe that

Magic seems to be getting more and more popular every day among the society people and is used by them very often, for the diversion of an evening. Sleight of hand is interesting and helpful in many ways as it creates not only a grace of manner and fluency of speech, but it develops the muscles in the hands and makes them limber and supple.

If magic’s popularity as a fantasy hobby sprung from the desire to emulate the wily success and devious charm of the professional performer, the understanding was that, in pursuing magic, men could learn to have the same control over others that magicians had over them. The prospect of this power and control was not at all confined to performing pleasant parlor tricks, just as the benefits promised to the student of sleight of hand extended beyond the sleight itself to “a grace of manner and a fluency of speech.” The magic industry intentionally conflated stage performance with the performance anxiety present in everyday life, compounding its allure to the amateur by tapping into both his fantasies and his reality.

Most of THE SPHINX’s subscribers were not professional magicians, but otherwise-employed amateurs. From its inception THE SPHINX was intended to be a forum for both the professional and the amateur. The third issue contained an Editor’s Note that articulated perfectly the purpose of the publication. It begins,

Last November I devised a scheme for creating a friendship among all magicians and lovers of magic. I called my society ‘The Order of The Sphinx.’

I already have several members, but I am desirous of spreading its influence far and wide, and I therefore take this opportunity of placing it before my readers.

The creation of the Order of the Sphinx was an attempt to formalize and energize the loose community of magicians who had already flocked to the magazine as passive subscribers. Significantly, though, the Order was not exclusively for professionals, but for “all magicians and lovers of magic,” between whom the Order offered to create a common bond. The Editor’s Note continues,

Each member has to faithfully promise never to expose any trick or sleight to an audience under any circumstances whatever. Each member will wear a small button on which is engraved the head of the Sphinx. Two perfect strangers wearing buttons happening to meet will at once become friends. Full particulars, together with a membership form, will be forwarded to my readers if stamped addressed envelope is sent.

Here, the editor William J. Hilliard invoked the powerful suggestion of the Order of the Sphinx as a secret guild. He imposed rules of conduct, including what amounted to a vow of secrecy. This vow was purely for effect; its purpose, and the purpose of the members’ button, was as much to make the members feel like insiders as to keep non-members out.

Real professional magicians did read THE SPHINX. Its issues were littered with letters from famous magicians and accounts of notable visitors to THE SPHINX’s headquarters. For the professionals, it played its role as the center of organization for a fundamentally decentralized group of individual magicians. The October 1902 issue contained seven and a half pages of advertisements and professional gossip – and a mere three and a half pages of actual magic tricks and advice. For the professional, this made it essentially a community newsletter; for the would-be amateur, this made THE SPHINX the printed manifestation of a magical performance: a vision of intrigue, secret knowledge, and male camaraderie.

What the editor of THE SPHINX realized when he promised his readers in the first issue that “nothing will be left undone to make this Magazine welcome every month to the amateur and professional Magician alike,” was that by making it welcoming and attractive to professionals, he was making it attractive to amateurs. Amateurs subscribed in droves to get their voyeuristic fix; to be able to spy on the world of the magicians they so admired and envied. As for making it welcoming to amateurs, this imperative became a drastically more important focus as THE SPHINX matured. The March 1905 issue contained a section titled simply “Amateur’s Column,” conducted by T.J. Crawford of Bowling Green, Kentucky. Between the “Amateur’s Column” and the emergence of a recurring feature called “The Easy Path to Wizardom” – whose cheery header contained two gnome-like creatures holding up signs proclaiming “BEGINNERS INVITED” and “WELCOME” — THE SPHINX focused on steadily becoming more and more inviting to what it must have realized was the bulk of its audience.

Despite every attempt to integrate the concerns of professional amateur magicians into a haphazardly cohesive whole, the tension between the two constituencies put a strain on THE SPHINX and on the magical community in general. A stock feature in any given issue of THE SPHINX was some variety of lament over the uninventive state of magic at the time. An article in a 1902 SPHINX titled “Inventors Needed: Many Magicians Have That Tired Feeling” complained that “One of the most notable characteristics of the average successful magician is his utter indifference toward the literature of his professional art. Is this not one of the reasons why less progress is being made along new lines, and why the same old programs are followed year after year?” The knowable secrets, whose appeal had drawn so many to magic in the first place, had become tired and far too familiar. The article continued,

The times have bred a race of shop magicians who, having acquired the necessary digital skill to handle a few simple tricks, set themselves up in business and look to magical dealers to keep them supplied with an occasional new trick. Half of the regular outfits are simply professional models of tricks that in cheaper form are sold in the toy shops for the personal entertainment of the youth of our land, and there are hundreds of boys 12 years old who are as well posted on the methods of manipulation as are the magicians themselves.

Herrmann the Great once wrote that, to be a magician, “One must be a palmist, a mechanic, a chemist, a designer and inventor, with mental faculties quick as a flash and with industry that never tires.” These were the qualities that had driven the magical profession to fame in the first place; these were the exemplary male characteristics that had supposedly separated magicians from regular men. Once the framework of the magical industry had emerged, the products and magic tricks which had been developed to satisfy hobbyists perverted the supposed purity of the profession.

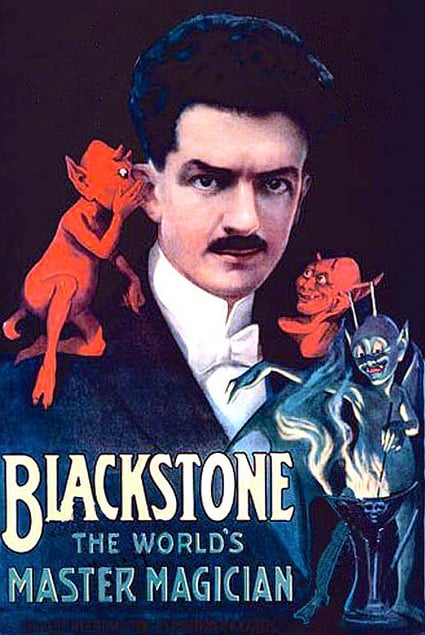

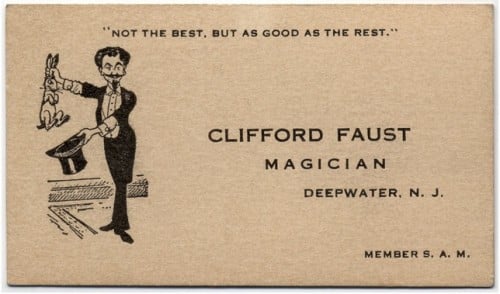

The inclusion of the amateur in the magical community, his proximity to the magicians he admired and envied, also fostered something of a cult of magic. Within this cult, the magician was the epitome of man; given this level of worship, it is small wonder that he became egotistic and smug. This self-compounding cycle manufactured complacency in the magical community – and, consequently, unrest. Only pages after the “Amateur’s Column” by T.J. Crawford, THE SPHINX printed an opinion piece on the deterioration of magic as art, which lamented that “There are too many ‘wonderful’ magicians in the business, to many ‘greats,’ too many men with ‘marvelous fingers’ and ‘phenomenal hands.’”

The solution to these two problems arrived at by the magical community was to institute a code of honor, which manifested itself as the High Standard of Magic. It was a retroactive response to the decline in innovation within the magical community and a desperate attempt to restore the respectability of professional magic – not to mention, the dangerously dwindling glamour of mystery. A 1903 issue of THE SPHINX implored that “The fascination of magic lies in its mystery, its charm in the grace and ease with which it is accomplished,” continuing that

To expose a trick — be it never so simple or old — is magicidal. It brings disappointment to the audience and, sooner or later, failure to the exposer. There is such a thing as good burlesque magic without any exposure of the method, and this brings just as good a “hand” and as much laughter as any performer could desire. There is as much room for burlesque magic as there is for burlesque drama, but there is no room either on or off the stage for exposures of magical tricks, either mechanical or sleight of hand.

This article, and all others which so deplored the exposing of magical secrets, were earnest in their concern for the profession. Something was deteriorating in the effect of the mystery of magic, and the blatant dissemination of technical secrets seemed an obvious culprit. But, whether they knew better or not, the stern critics of exposing were skirting around the real problem: that magic, a profession which had made its name on the mystique of individuality and the charisma of individual performers, was having a problem with quality control. In the democratization of the magical profession, its very power was diluted by the inclusion of clumsy beginners in its ranks.

The solution was: community. The article on the need for inventors in the 1902 SPHINX remarked that “The magician, almost as much as the physician, needs to come into contact with other minds than his own that he may avoid getting into a rut and becoming a ‘has-been,’ and that he may sharpen his wit, broaden his conception and be led into fresher fields of endeavor.” The way out of this rut, and to engender a sense of responsibility and honor into the bargain, was to form local magic clubs in which ideas could be exchanged and a more immediate kinship than that provided by a monthly magazine subscription could be fashioned.

Where THE SPHINX had emerged to build the national community of magicians, a publication entitled THE COMBINED MAGICAL CLUB BULLETIN came forward in 1915 specifically to coordinate and enable the accelerating formation of these local communities. By giving substance and form to the abstract “friendship among all magicians and lovers of magic” first attempted by the Order of the Sphinx, local magical clubs conferred weight on the pretenses of the High Standard of Magic. As local centers of quality control, the clubs reined in what had been a free-for-all of magical democratization and subsequent dilution.

Local magical clubs could enforce rules and regulations where THE SPHINX had never succeeded. But no attempt was made to reverse the infiltration of the amateur into magical circles; by the time local magical clubs emerged, the amateur was an essential fixture in any magical community. In fact, the foremost magical club in the United States, the Society of American Magicians, was co-founded by an amateur magician, Dr. Ellison. Ellison’s interest in magic was described like so:

Some years ago Mr. Ellison learned to do a few card tricks, and, becoming interested in magic, purchased two books on the subject. Now he has close to a thousand titles, and the books run all the way from the Holy Bible (wherein is found the earliest account of magic and miracles), down to the latest edition of that wonderful book of Nelson Downs.

These magical societies were strange fusions of fan club and professional guild, in the same way that THE SPHINX had attempted to romance the amateur while providing genuinely useful information to the professional. Every issue of THE SPHINX contained notes on “Magician’s Doings,” which in some months consumed a full quarter of the publication. Most of the notes were somewhat perfunctory and inane; the magical society of Boston reported in one issue of THE SPHINX that they had “received a handsome set of photos of Dalvine, the European prestidigitateur, who will shortly be seen in Boston and New York, presenting original ideas and novel effects.” Taken together, though, these notes provide a glimpse into the dynamics of the magical community.

Magical clubs, like magical periodicals, allowed the amateur or worshipful fan the illusion of insider access to the society of dashing magicians whom they so admired. But it was only an illusion; only an extension of the magician’s stage performance. THE SPHINX and the Society of Detroit Magicians alike appealed to the amateur by pretending to be for the professional, all the while perpetuating the powerful cult of magic.

As for the magicians generously revealing their secrets to the magical community of which the amateur was a part, this too was fundamentally an illusion. A true magician would never reveal his real secrets; techniques of prestidigitation and card manipulation, maybe, but not the enigmatic sources of his mesmerizing presence. Amateur magicians operated under this illusion, believing that in the dedicated pursuit of excellence of this novel fantasy hobby, they would stumble upon the charisma and control which they had marveled at and lusted after. The industry of magic intentionally perpetuated the false hope that, by following a few simple instructions, any industrious fellow could transform himself into The Spectacular Mesmerist or The Man with the Marvellous Hands.

That amateur magicians wholeheartedly believed in this despite all evidence to the contrary is evidence of the very strongest and most courageous sort of magical thinking.