Bathybius!

By:

March 7, 2012

A couple days ago, Jacob Mikanowski (a graduate student in European History at U.C. Berkeley, currently living in Warsaw) published an excellent piece in the LA Review of Books that’s ostensibly about the Polish author Bruno Schulz. But buried inside is a short history of Bathybius haeckelii, the primordial ooze, its life in science, and its afterlife in science fiction. There’s some stuff about actual radium too, as well as Karel Čapek’s ooze-derived robots.

Excerpt:

Bathybius was not the universal precursor to all life, but despite its debunking, living matter continued to have a career in the shadowy corners of fin-de-siècle science. For a few years after Marie Curie’s discovery of radium in 1898, it seemed as if radioactivity might hold the secret for the production of artificial life. Radium itself seemed strangely alive. It gave off heat and powerful rays of energy; it glowed with its own light and decayed into other elements. After Ernest Rutherford and Frederick Soddy discovered that radioactivity indicated the transmutation of elements, they named these new radioelements metabolons for their ability to reproduce.

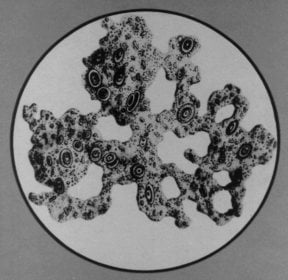

If the radioactive elements were partially alive, it stood to reason that they might make inert matter come to life. John Butler Burke, a young scientist at the Cavendish Laboratory in Oxford, a hotbed of early research into radioactivity, sought to test this hypothesis. In a 1905 experiment, he claimed to have demonstrated radium’s vitalizing force. By adding a bit of radium to a petri dish of sterilized bouillon, Burke produced an array of dynamic cellular forms which seemed to grow and divide over a period of days. He named these semi-living organisms, part-radium and part-microbe, “radiobes.” A subsequent experiment by C. Stuart Gager of the New York Botanical Garden claimed to show that “radium rays act as a stimulus to living protoplasm.” Radium was life-giving and life-enhancing. Because of these imagined properties, a radium craze swept America. Dozens of products were rushed to market to cash in on its health-giving power: from radium water, a “liquid sunshine cocktail,” to radium chocolates, crucifixes, and suppositories.

Also:

The first robots in modern fiction, in Karel Čapek’s 1921 play R.U.R, likewise owe their existence to speculation about synthetic life. Čapek’s robots are not mechanical. Their inventor, Rossum, begins his career studying ocean fauna on a distant island. Before long he decides to “imitate the living matter known as protoplasm” by chemical synthesis, and he soon discovers an “artificial living matter” out of which he can manufacture any form of life, including the proletarian.

This equation between the formlessness of protoplasm and the mutability of the working class is also present in H.P. Lovecraft’s fiction. In At the Mountains of Madness, the star-shaped alien Elder Ones who build a civilization in the Antarctic are aristocratic, art-loving socialists. Their slaves, the Shoggoths, are shape-shifting monstrosities created out of “viscous agglutinations of bubbling cells” able to mock and reflect all forms and organs and processes. Even on the nightmare plateau of Leng, the proletariat appears as a shapeless ooze, an anarchic, resentful, fetid mass trapped between life and non-life, sentient only in so far as it can mimic its departed masters.

Mikanowski tells us: “I think that Radium Age science fiction wasn’t just a good but neglected period for SF. It’s woven all through the funky Central European offshoots of Modernism, from Schulz to Čapek to Thomas Mann.”

Yes!

MORE RADIUM AGE SCI FI ON HILOBROW: HiLoBooks homepage! | What is Radium Age science fiction? |Radium Age 100: 100 Best Science Fiction Novels from 1904–33 | Radium Age Supermen | Radium Age Robots | Radium Age Apocalypses | Radium Age Telepaths | Radium Age Eco-Catastrophes | Radium Age Cover Art (1) | SF’s Best Year Ever: 1912 | Radium Age Science Fiction Poetry | Enter Highbrowism | Bathybius! Primordial ooze in Radium Age sf | War and Peace Games (H.G. Wells’s training manuals for supermen) | Radium Age: Context series | J.D. Beresford | Algernon Blackwood | Edgar Rice Burroughs | Karel Čapek | Buster Crabbe | August Derleth | Arthur Conan Doyle | Hugo Gernsback | Charlotte Perkins Gilman | Cicely Hamilton | Hermann Hesse | William Hope Hodgson | Aldous Huxley | Inez Haynes Irwin | Alfred Jarry | Jack Kirby (Radium Age sf’s influence on) | Murray Leinster | Gustave Le Rouge | Gaston Leroux | David Lindsay | Jack London | H.P. Lovecraft | A. Merritt | Maureen O’Sullivan | Sax Rohmer | Paul Scheerbart | Upton Sinclair | Clark Ashton Smith | E.E. “Doc” Smith | Olaf Stapledon | John Taine | H.G. Wells | Jack Williamson | Stanisław Ignacy Witkiewicz | S. Fowler Wright | Philip Gordon Wylie | Yevgeny Zamyatin