Zooming Through Space

By:

January 5, 2012

This article was first published in Hermenaut #13 (Summer 1998). Hermenaut was published and edited from 1991-2000 by HiLobrow cofounder Joshua Glenn. Click here to read more from Hermenaut and Hermenaut.com.

In a typically uncomfortable paradox, Pascal observed: “By space, the universe envelops me and swallows me up like a point; by thought, I envelop it.” This could be a motto for all who zoom. And which of us doesn’t? Once a novelty, the zoom is now the optical standard of technological culture.

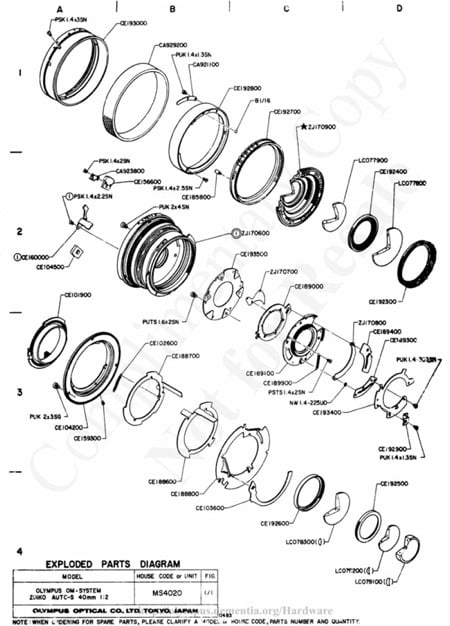

Since all but the cheapest still cameras and all video cameras now have zoom lenses, practically anyone who has used a camera is familiar with the zoom’s telescoping effect. You can stay in the same place, point the camera in the same direction, and the detail in the image you see will be magnified or minimized. Zoom in, and you cut out from its horizon the object of your interest. Zoom out, and you see it in a dense visual context.

The institutional use of the zoom in documentaries and TV news mirrors its underground use in home movies/video and pornography. Filmmakers zoom in on event-fields not subject to their prior control, like sporting events and impromptu encounters with politicians, celebrities, and suspects on live cop shows. But the opportunism with which the zoom greets reality is also a subjection, a submission. In zooming, the filmmaker confesses a powerlessness to intervene other than optically in an event whose flux s/he is doomed merely to follow. The filmmaker always lags behind the event: The zoom compensates for this delay, but it also registers it.

Unwilling to accept this implied helplessness, Hollywood long banished the zoom from its productions, designed as they were to show complete mastery of everything visible. Silent film maverick Allan Dwan tried an early experimental zoom lens in 1929 for Tide of Empire and was dissatisfied with it. Forty years later, he said: “Even today it doesn’t have the effect of movement, but the effect of extension. It just seems to open up instead of move.” Zooming didn’t catch on in Hollywood until the mid-Sixties, with the success of foreign films to which the zoom lent a Now aura: A Hard Day’s Night, A Man and a Woman, etc.

Through its ordinary use in films and TV, the zoom has come to seem “real,” even though it denies the cinema’s illusion of reality, offers nothing to bolster that illusion (cf. Dwan’s comment). Forgetting its negativity, we’ve learned to accept the zoom as part of how the world looks when represented, even though it has no correlative in our own unmediated experience of the world.

Generally, filmmakers use the zoom’s independence from the real space of the image just as a convenience or an economy, without bringing into play the underlying assertions of the technology. The zoom facilitates long takes, which save money in postproduction by shortening editing time. It can also save time on production by subbing for camera movement, which is usually more logistically complicated. The distinction between the zoom and camera movement is crucial, however. Camera movement is round; the zoom is flat. Camera movement is concrete and explores physical space; the zoom is abstract and has to do with a psychologized, relational space that opens up or shuts down. As Osip Mandelstam states Henri Bergson’s concept of the spatial, internal connection of phenomena: “Phenomena thus connected to one another form, as it were, a kind of fan whose folds can be opened up in time; however, this fan may also be closed up in a way intelligible to the human mind.” That’s how the zoom connects images.

Certain filmmakers have from time to time revived zoom’s radical potential. Roberto Rossellini, who pioneered the neorealist movement in the Forties and continued making films that documented postwar malaise with an ethnographer’s (and a philosopher’s) eye, was one of the first major directors to embrace the zoom. The series of historical films he made from 1964 to 1976 shows the full flowering of his zoom aesthetic. In these magnificent films — whose general unavailability should be a scandal — Rossellini gets audiences interested in long discussions (adapted from historical texts) about man, God, art, and science. With simple sets and costumes and a few extras, and with amateur actors who are kept from imitating movie acting, each film creates an exact visual and behavioral idea of its period — the Athens of Socrates, Florence of the Medici, the world of Saint Paul — getting the viewer to share Rossellini’s amazement at the things people did, and ultimately to understand their beliefs and prejudices. As we witness characters making choices, affecting and being affected by their worlds, we understand, as we do in only a few movies, and rarely enough in life, what it means to live in freedom.

Rossellini’s zooms create a new kind of cinematic rhythm: an optical rhythm. In Augustine of Hippo (1973), the zoom is in tempo with the actors’ movements. The camera slowly zooms in, then out on a scene in a 4th-century hair salon. When a dark-robed man strides into the shot and sits in the background, the zoom becomes quicker, more determined, matching the quality of the entrant’s movement, and then stops momentarily, as if to give the eye of the viewer time to adjust to this new element of the scene.

The zoom also structures events in a way that feels improvisational. A traveling Christian gives bread to a beggar woman. In the background, he walks toward her (and us); simultaneously, a girl enters the frame from behind the camera and walks toward the other two. The camera zooms in. When the group breaks up — the girl turning and running back out of frame, the man rejoining his traveling companions — the camera zooms out again, then back in on the woman alone, watching them go. The flattening/expanding of the visual field creates an illusion of different time-feelings converging and splitting.

Rossellini’s zoom is lulling, liquid. We become immersed in the wash of the film (an impression reinforced by the soundtrack, which mixes Mario Nascimbene’s ambient electronic score with real sounds that issue from no visible source). As characters walk toward the camera, the camera zooms out; as they walk away, it zooms in, suggesting that they are getting nowhere. Zooming in and out on streets, the film emphasizes the eternity of its moment: the transition between a once-mighty state (“Our civilization is finished,” declares a Roman) and a new, as-yet unclear social formation. As Augustine says to one of his followers during a rest stop: “The story of man and the world is like this road. We move freely on it, but the road leads us to our destination. Whoever leaves the road perishes in the desert. Whoever stops and turns back will be surprised by the night.”

Horror director Mario Bava started his career as cinematographer on two short films directed by Rossellini. Perhaps at some point on his road he stopped and turned back. In any case, Bava, adopting principles opposed to Rossellini’s, became the second director to use the zoom in a visionary way. Kill, Baby, Kill! (1966), one of Bava’s masterpieces, shows that Bava is preoccupied with the question: What is the relationship between fear and space?

This richly atmospheric and imaginative, yet bizarrely minimal and perversely insane Gothic horror film takes place during a single night in a small central European town. For years, the town has been terrorized by the ghost of a little girl named Melissa. “Just poverty and ignorance, combined with superstition,” is how the film’s muscle-headed doctor hero diagnoses the problem. Yet the dead Melissa keeps popping in and out, leaving corpses in her wake, her appearances always heralded by a disembodied giggle and the bounce of a white ball.

Bava’s policy, followed almost rigorously throughout the film, is to use the zoom to show the impact of the supernatural. When a woman lying in bed sees Melissa outside her window, Bava first zooms in slowly on Melissa’s hand against the window pane, then cuts to the woman, then shock-cuts to a fast zoom-out from the window. For the rest of the scene, all shots of the woman involve camera movement toward, around, and away from the bed, while all the shots of Melissa at the window are zooms. Bava creates two worlds, two separate visual regimes, and shows their optical interaction: a metaphor for the cinema.

Taking the point of view of a child on a swing, the camera zooms in and out on a gap between trees in a graveyard. By dollying back and forth slightly at the same time, the camera creates a vibration in real space, which the zoom — fast, and at a fairly great ratio between widest and narrowest field — hyperbolizes into an immense, dizzying perceptual shift. Later, in a scene in a crypt, the camera zooms from behind the heroine’s shoulder to a little square window in the door through which the hero, on the other side, looks in at her. While zooming, the camera tracks forward slightly toward the heroine’s back. As in Hitchcock’s Vertigo, zoom plus camera movement equals perceptual dissonance. The image seems to cut her body out from the space and lift it toward the viewer, before the camera abandons her, swinging to the right and zooming onward.

Bava’s camera proficiency, while providing plenty of movie kicks, is never thoughtless. He understands, for example, that if he’s going to use the hackneyed overhead angle shot of a person going up a spiral staircase, the person must look up toward the camera to underline the purely optical nature of the composition. The opening in the middle of the staircase is one of the empty spaces in the film (like the gap between the trees in the graveyard) that draw the viewer’s eye in, endlessly. Near the end of the film, when it reaches its peak of deliriousness, Bava returns to the same staircase to zoom in and out of the spiral and then rotate the image. The point is to confront the viewer with an inescapable visual distortion, to make the cinema a problem.

Spanish director Jesús “Jess” Franco’s use of the zoom is notorious. In Franco’s films, zooming is so compulsive, so pervasive, at times seemingly so random, that it serves as a formal imperative that justifies the existence of the film. Franco represents cinema in decomposition. Crudeness of technique is the index of the reality of the event, like a glaze spread over the actors’ bodies and the decor. The removal of the face of a person condemned to remain conscious during the procedure (this happens in Franco’s Faceless) is a metaphor for Franco’s cinema: separation of the skin, the surface, from the eyes, vision; pure perception of a body anesthetized into pure fascination.

Franco’s Tender and Perverse Emanuelle (1973), a softcore answer to Otto Preminger’s Laura, explores in flashback the life of a nymphomaniac concert pianist who apparently knows only one piece (the film’s theme song, incessantly repeated). As usual, the director’s attitude is poised somewhere between exploitativeness and a dry romanticism. “She lives detached from the world, lost in some daydream,” her husband tells a psychiatrist. Franco doesn’t ask us to believe in the characters, only in the mood of obsession that mothballs them. The tone Franco imposes is flat and dead, but it’s also bewildering and mesmerizing, precisely because of the push and pull of the zoom.

The scene of Emanuelle’s piano recital is a good example of this. The camera zooms in on her husband, Gordon, watching from a balcony, then cuts to a high-angle shot that zooms in on Emanuelle playing. The zoom-in on Gordon is repeated, but more quickly; he looks concerned. The shot pans to his sister sitting at his right, then zooms all the way out to the piano on stage. This cuts to a medium close-up of Emanuelle that zooms out slightly. She stops playing, distressed. Here Franco intercuts shots that zoom in on Gordon and on Emanuelle, who looks up at him. Then Emanuelle resumes playing, and the camera zooms out from her. And so on.

The scene’s point apparently is that Emanuelle stops playing out of emotional strain, but her husband’s will, communicated through his look, compels her to go on. It’s possible to imagine other ways of shooting this scene, but Franco insists on the psychological value of the zoom and on the characters’ mutual entrapment. Emanuelle’s dependence on her husband mirrors his dependence on her. None of this is conveyed by the seemingly undirected acting — she should be called Ema-null — everything comes from the zoom.

Franco’s repetitive zooming implies the impossibility of movement and development. Denying not just pace (his movies are often painfully slow) but time, Franco’s is a deviant practice in the “entertainment” industry: that he managed to make more than 150 films within that industry is a 20th-century wonder.

It may seem a desecration, and it un-doubtedly is, to turn from Tender and Perverse Emanuelle to the work of Andrei Tarkovsky, a director who thought of cinematic form and his own artistic responsibility in the most rigorous way conceivable, and who would have ridiculed the idea of talking about his films in terms of a particular technique. Yet it can do no harm to notice that Tarkovsky’s films present a completely original and personal aesthetic of the zoom lens. Tarkovsky’s zoom is his consciousness. It’s the vehicle for the freedom from the determinism of time that he reclaims in the name of identity, memory, history.

Tarkovsky’s Mirror (1975), a film that must wring emotion from even the most insensitive viewer, is an exploration of memory, family, and dream that’s basically indescribable. Tarkovsky said, “Anyone who wants can look at my films as into a mirror, in which he will see himself.” Throughout the film, we see fragments of different stages of the main characters’ lives, not in chronological order, but linked by a word, a visual idea, an association, in a way that the director called “turning time back through conscience.” Each shot is vivid and actual. We become aware of an inconsolably tragic experience of the past, and at the same time of the triumphantly tragic power of great art.

In the last shot, an old woman and two children walk away from the camera across a field. The camera tracks diagonally — sideways and back — so that birch trees begin to fill the space between the people and the camera. Suddenly, the camera zooms in, as if seized by the urge to catch up with the people and unwilling to let them go, or perhaps simply to test and affirm again, for the last time, the reality of the curtain of woods that’s just interposed itself (the woods are a major element in the film, surrounding the childhood home, the privileged outpost of memory and meaning, from whose orientation the last shot is implicitly taken). This impulse is only momentary, and the camera immediately zooms out, continuing its gliding movement backwards, the trees becoming thicker.

The Tarkovskyan zoom is spirit, breath (the zoom’s movement into the landscape echoes the mysterious wind that blows across the field near the beginning of the film). It realizes the promise of photography: unmooring perception from space. At the same time, it insists on the earth and its presence.

Tarkovsky brings us out of the cinematic world that surrounds us and takes us back into the real world. Which is sort of what Rossellini does, too, and which is the reverse direction from most films’ trajectory. Commercial cinema and television practitioners always labor to fill up given time quantities; their products rarely manage to distract us completely from the depressing awareness of the time we waste in consuming them. In standard movie and TV usage, the independence from space granted by the zoom merely reinforces the arbitrary regime of time. On the other hand, Rossellini, Bava, Franco, and Tarkovsky use this independence to deplete time. They show that a movie is not just entertainment, but the imaginary collapsible space of our relation to the world.