Pure Evel

By:

December 24, 2011

This article was first published in Hermenaut #13 (Summer 1998). Hermenaut was published and edited from 1991-2000 by HiLobrow cofounder Joshua Glenn. Click here to read more from Hermenaut and Hermenaut.com.

It’s not much, the flying dream. Basically, I can fly. Actually, it’s more of a soaring thing. No wings, no arm flapping — I just… soar. But if I think about it, if some stray, niggling doubt worms its way into my mind and points out that I’m floating 300 feet above my backyard, then the flying dream turns in an instant into the falling dream. And suddenly my backyard is a lot closer than 300 feet, and suddenly my heart is on rapid-fire, and suddenly my body seizes from head to toe and I’m awake.

I think I’m having the flying dream right now. I really shouldn’t be thinking about this.

Cut. Back up. Set the scene.

I work as an editor for a well-known, well-trafficked Corporate Website, for which my writing lately consists mostly of blurbs, promo copy, and the like. Although I used to make a living with my pen and a mini-recorder, it’s been a while.

But right now I’m in Clearwater, Florida, where Evel Knievel is recovering from surgery to replace his left hip, which he recently injured in a fall during… a round of golf. I’ve been sent by my employer to interview the 59-year-old former daredevil.

Actually, the interview is only part of my mission. Officially, my mission is to act as an ambassador for my Corporate Website and to persuade Evel to write an advice column for us about risk-taking. Basically, I’m here to make Evel Knievel the Ann Landers of the Internet. And to interview Mr. Knievel for a puff piece which will run alongside his first column installment. Sample interview question: “Evel, you’ve done some crazy, crazy stuff in your life. No, really — some nutty, nutty stuff. Tell me, Evel: What’s the craziest, nuttiest thing you’ve ever done?”

But my [ex-]boss is also the publisher of Hermenaut, and that brings me to the unofficial part of my mission: To exploit my offically-sanctioned access to the Knievel compound to quiz Evel for this publication about his lifelong love affair with danger. Specifically, to get at his relationship with the abyss, that literal and figurative chasm of fear which he so frequently overleapt during his career as America’s most renowned daredevil. Sample question, as suggested by Hermenaut’s editors: “Baudelaire wrote, ‘Pascal’s Abyss went with him, yawned in the air — / Everything’s an abyss! Desire, acts, dreams / Words! I have felt the wind of terror stream / Many a time across my standing hair.’ Evel, does your abyss go with you everywhere? Explain.”

I am thrilled by my mission. “I’m going to meet Evel Knievel,” I tell friends and acquaintances with no small measure of pride. “I’m going to interview him in his home.” But my mission terrifies me, too; I am, as I said, a bit rusty as a journalist, and Evel Knievel is not what I’d call a gentle warm-up. And I’m particularly frightened by the unofficial part of my mission. Evel Knievel does not strike me as the type of man I want to quiz about French poets. He is not a man I want thinking that I’m mocking him. On this point, I fear for my safety.

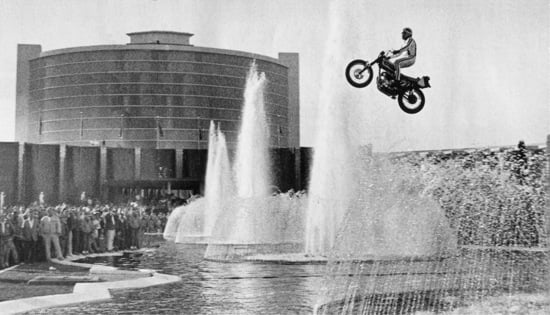

It’s not unfounded, either, this fear of mine. You know what a tough S.O.B. Evel Knievel can be. You know about Las Vegas, 1968, when he tried to jump the fountains at Caesar’s Palace and instead landed in a month-long coma. About the Wembley Stadium jump in 1975, in which he broke his pelvis in two after failing to clear 13 double-decker buses. And how’d he follow that? By going for 14 Greyhounds at King’s Island, Ohio, just five months later, that’s how. And nailing it down cold.

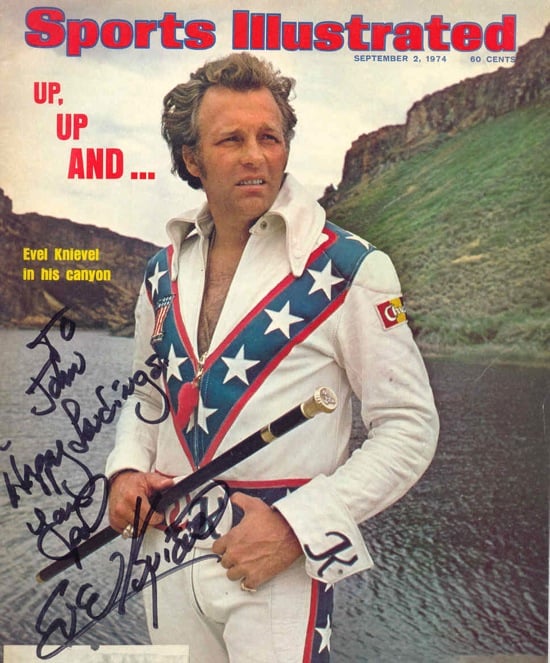

And you know about the debacle at Snake River Canyon on September 8, 1974 (the same ignominious day on which Ford pardoned Nixon). The one where Evel strapped himself into his jet-powered “Skycycle” and tried to blast his way over a river gorge, a gorge he had to buy because no one wanted his blood in their river. After sending two unmanned test cycles to their destruction on the canyon floor, Evel climbed into the third and last cycle because, what the hell, he’d already promised his fans he’d do it. Sure, his parachute opened on lift-off, and he ended up floating ingloriously down to the bank of the Colorado River; it was Evel Knievel’s biggest failure, a humiliating defeat broadcast live on national television. But would you have tried it?

This stuff, this you know about, and this I can deal with. I’m in awe of the man, but this stuff doesn’t make me fear him. What you probably don’t know about — and this part’s got me just a mite jumpy right now — is that fat, snarling devil that lives on Evel Knievel’s shoulder. You probably never heard about how, growing up in Butte, Montana, Robert Craig Knievel — Bobby — was known around town as a holy terror, a kid who once proved that, while you may not be able to beat City Hall, you can at least blow off the front door and clean the place out. You probably know nothing about how he went into business for himself as a “merchant policeman,” charging Butte storekeepers 10 bucks a month to protect against burglary or vandalism — by him.

And I’d bet a week’s pay that when you hear the name “Evel Knievel,” you don’t think of the man who, though slowed by two broken arms from yet another failed jump, loaded up on Wild Turkey (his drink of choice), chased down his biographer, and “very carefully” busted the writer’s arms with a baseball bat because Evel Knievel on Tour didn’t quite meet with its subject’s approval.

“The guy that wrote this book,” Evel said later, “was lucky I didn’t kill him. What I wanted to do was get this guy, strip him, hang him on the corner of Hollywood and Vine from a light pole, and I wanted to take this book, cover it with Vaseline, and stick it right up his ass, and let him hang there.” Despite this admirable display of lenience, Evel spent 6 months in jail, time enough to learn a valuable lesson: “The next time I’ll handle it a little differently,” he said. “The next time I’ll send somebody.”

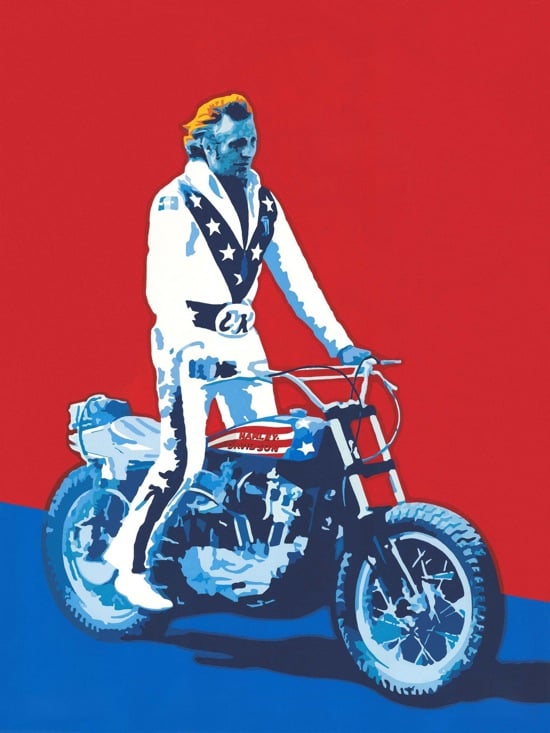

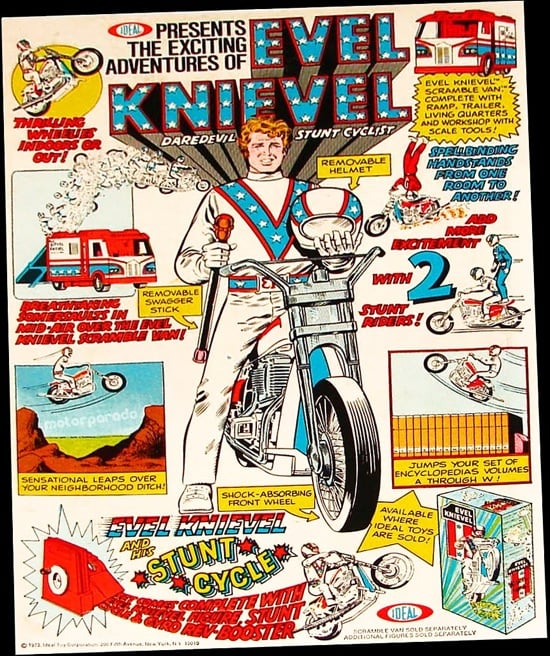

The Evel Knievel you know is the guy whose toys you used to abuse, whose image sold 300 million dollars’ worth of dolls, watches, pinball machines, and lunchboxes in the late ’70s and early ’80s — more, Evel claims, than Barbie and G.I. Joe combined. You know the guy in the red, white, and blue jumpsuit, the Amer-I-Can hero. When you think “Evel Knievel,” you don’t think of a lawless, bat-wielding thug with a wicked temper and a taste for vengeance. But I do. In fact, right now, that’s just about all I can think of.

So this is where I am. It’s Tuesday. Tomorrow, I meet Evel Knievel. Yep, it’s the flying dream. Don’t look down. Don’t think. Only way to do it is just to do it.

I’m scared.

“Make sure you bring that contract.” I’m on the phone with Mike Grey, Evel Knievel’s business manager. We’re planning the next day’s rendezvous. It’s the third time thus far in what has been a very short conversation that he has reminded me to bring the contract for the advice column. I promise him that I will. He tells me where he’ll meet me, tells me what he looks like.

“And remember, bring the contract. Evel won’t like it one bit if you show up without that contract.”

I picture Evel Knievel hobbling after me, bat in his hand and rage in his eyes, his aluminum walker cutting a path in front of him. I will not forget that contract.

I’ll tell you something, 24 hours can take weeks when you’re hotly anticipating a meeting with a boyhood icon. I’ve checked and re-checked the batteries in my recorder. My interview is practiced and polished, all my questions neatly printed on a yellow legal pad. I’ve got some pretty great questions, too — some my own and some from the people at Hermenaut, but all of which I can’t wait to hear him tackle.

I’m going to ask him about why he did what he did. It’s an obvious question, but he once said that “life is an everyday battle at keeping death at a comfortable distance,” which doesn’t seem to make sense coming from a guy who spent most of his life riding a Harley Davidson straight at death. So why did he do it? I’m going to ask him about the moment of lift-off, the point of no return just as his bike would leave the ramp. Did he feel out of control at that instant? And was this a good feeling or a bad feeling? I’ll ask about the times he knew he wasn’t going to make it out of a jump in one piece, like at Wembley, and yet he jumped anyway. Other than the money and fame, what the hell did he get out of these jumps — what personal abyss did they address — that made them worth the three years’ aggregate time he estimates he spent in hospital beds? Three years! And now that he’s shuffling around like a man 20 years his senior, does he still think they were worth it?

Yeah, I’ve got lots of questions, but as yet I’ve got no Evel to ask them of — just some time to kill. To occupy my restless mind, I compile a list of all the fabulous Evel puns I intend to use in my story:

“…I am thrilled to finally be in the presence of Evel…”

“…I have seen where Evel lurks. I have peered into the heart of Evel…”

“…I have met Evel’s woman, 27-year-old college student Krystal Kennedy…”

“…Knievel is upset when I ask about his son Robbie, the lesser of two Evels…”

“…Undaunted by his threats, I look directly into the Evel eye…”

“…I find that I am annoying my friends with my puns. They tell me, ‘Dan, you’ve got to change your Evel ways…'”

Oh, man. This is gonna be fun.

It’s Wednesday. EK-Day. Mike picks me up and drives me back to his office to await my appointment with Evel, who’s spending the morning practicing his putts. It’s been less than a week since Evel got the go-ahead from his doctors to start golfing again, and so far he’s been on the course every day. He can’t actually play just yet, so he practices.

Meanwhile, Mike and I sit in the newly converted tattoo parlor that serves as Mike’s office (in his day job, he handles marketing for a Web development firm), and Mike entertains me with stories about Evel’s golf game. He says that Evel is constantly coming up with foolproof “theories” on the game, each one contradicting the one before it. He tells me that Evel tapes little notes to himself on his clubs, last-minute reminders to “keep your head down, Dummy” and the like. Suddenly I’m not so tense. I’m not thinking of the baseball bat. The fear is drifting away. Hey, Evel’s just an endearing old golf nut. He could be my Uncle Moe from Queens.

It’s time. Mike calls Evel to let him know we’re coming. Evel drops the phone as he answers and fumbles after it for two, three seconds. Mike and Evel laugh. “Clumsy old fart.” I laugh too. Just like Uncle Moe.

Still, my palms are sweating as we pull up next to Evel’s black Aston Martin, parked in the handicapped spot in front of his apartment building. Hey, that’s Evel Knievel’s car, after all. We ride up to four, and I follow Mike down the hall to the right. And check this: Evel’s front door is completely average. No ring of fire to pass through, no red, white, and blue paint job, not even a wooden sign that says “the Knievels.” But a chill darts up my back anyway. I mean, come on — I’m about to enter the home of Evel Knievel!

Mike knocks and opens the door. “Evel, you there? It’s us.” He’ll be out in a minute. He’s, er, indisposed at the moment. My nerves settle just a bit more. Sure, he’s the most fearless daredevil the world has ever known, a man who, as his son likes to say, invented his own sport. But when it comes down to it, he’s just a regular guy. He has to answer to his bladder, just like you and me and everyone else we know.

Evel Knievel’s apartment is strikingly ordinary. It’s a one-bedroom place, probably no bigger than yours. Modern, clean, with good air conditioning. Nice leather sofa. On the coffee table is a copy of Premiere and a few random women’s magazines. It’s the kind of place you’d expect right on a golf course, but it’s nothing lavish.

Of course, there’s no mistaking where you are. On the TV cabinet are two helmets — the famous white one he wore to jump over buses and canyons, and another one, decorated with a Bob Ross-style nature scene. There’s a script on the table for Pure Evel, the latest feature being planned about his life, with Matthew McConaughey rumored to be interested in the title role. And dominating the room from the wall behind the sofa is Evel’s self-portrait, an impressive oil-on-canvas of the artist riding a wheelie in front of a setting sun, his red, white, and blue scarf flapping in the wind behind him.

I take a seat on the sofa and prepare my recorder and my legal pad. In the bathroom the toilet flushes and I hear the sound of running water. I begin to stand up, but I’m too early; my body stutters back onto the sofa. 30 seconds later, it’s time, and I move to meet Evel as he enters the room one step behind his walker. I shake his hand. “Mr. Knievel, it’s nice to meet you. I’m Dan Reines.”

“Hi.”

And for the moment, he’s done with me. He peppers Mike with business-related questions as he settles into a leather recliner to my right. He wears black dress socks and white cotton briefs under a red, blue, and green terrycloth bathrobe. It’s a grandpa look; let’s call it convalescence casual. Surgery and age have left him gaunt; you could probably cut yourself on his collarbone.

This is not the outlaw thug I’d feared. He’s a man with a world of experience, a thousand stories for sure, but this is not a man who would — or even could — hurt me. At last, I’m calm. I’m ready. He winds down his conversation with Mike and turns to me, catching me staring.

“Now,” he says, sizing me up. “What the fuck company do you represent?”

Oh Jesus, I’m falling.

I’m paralyzed by his eyes. How could I not have noticed those thuggish eyes? They’re a deep, dead, charcoal gray, and they don’t appear to reflect any light. I stammer out the response I’ve been rehearsing all week. I tell him about my Corporate Website, and about the advice column. I tell him why we’re such a perfect fit for him, and explain how we consider him a sort of DIY folk hero. “…and what we’d like to do is provide a forum where young people can go to learn all about…”

“About my philosophy.”

Yes.

“My philosophy of life.”

Exactly, yes.

“So you bastards want to make me the God-damned Ann Landers of the Internet!”

What? No. Ann Landers?! Imagine! “Evel Knievel,” I say, “is not Ann Landers.”

Awful good comeback, I know, but Evel’s not satisfied. He has questions about the fee. He has problems with the terms of the contract. Now he’s starting to get riled up, and apparently he’s got a problem with my website, too.

“What the hell kind of Internet site are you, anyway? I don’t want to be in a position where I end up tied to some big loser, where I’m carrying you guys.”

Aha — excellent! A question I can answer! We’re not some rinky-dink site, I tell him. He’s lining up with a winner. “We’re the fifth-most visited site on the Web. We get four-and-a-half million people a day coming to our site.”

“Then you can sure as hell afford to pay Evel Knievel a lot more than you’re offering, can’t you!?”

Stupid, stupid, stupid! I dove into that trap! But he’s already left me behind. Now he’s ranting about some T-shirt-makers who asked him to support a line called “Die Trying,” and about those “No Fear” shirts and how they’re killing kids with that crap. Now he’s fuming about the people at ESPN and how they took advantage of him, and for the life of me I can’t figure out what that has to do with me, but he’s really starting to get worked up over this, and I’m getting a little bit nervous. I look to Mike for help, but Mike’s egging him on, saying stuff like “That’s right, Evel. Evel’s right.” So I’m nodding my head at both of them and I’m looking sympathetic and apologetic, and meanwhile I’m thinking about that writer again, the one with the broken arms, and I’m actually starting to wonder if this 59-year-old man, who can barely walk, is about to kick my ass. And then — I swear to God —I hear Evel’s old-man voice say “Who the fuck do you think you are?” and my heart lurches, and now I’m shivering.

I look around for an escape. The ground is getting closer. My body seizes, but nothing’s changed. This is not my falling dream. It’s a nightmare, yes, but it’s scarier than my falling dream. I have a feeling this interview ain’t gonna happen.

Apparently, Evel’s got the same feeling. We can do the interview another day, he says, when I come back with a better contract. How about a few questions, I plead, since I came all this way? No dice. His pain medication — synthetic heroin — is kicking in, and he needs to get to bed. He grabs his walker and stands up. I scramble to gather up my notepad and tape recorder, and before I can even say “Baudelaire wrote…” I’m back in the hallway, staring at Evel Knievel’s door. Crestfallen.

So much for my fantastic interview. So much for my fabulous puns. In the elevator, Mike does his best to console me. “Well,” he says, “you may not have gotten your interview, but you sure got a solid dose of Evel. Yep. That was definitely pure Evel.”

You always think of the best stuff to say after the door has slammed on your ass. It’s been three weeks since my meeting with Evel, and I’ve imagined a thousand ways things could have gone better. Like, for instance, I could have interviewed the man. The problem is, I can only remember one way the afternoon went, and it’s not a good memory. It was like Evel slapped down 35 cars in front of me and said “All right, hotshot, jump that. Then we’ll talk.” And me, hell, I couldn’t even find the damn ramp.