Wage Slavery — Discuss.

By:

December 23, 2011

The Wage Slave’s Glossary (Biblioasis) puts a humorous, scholarly, and critical “gloss” on contemporary office slang (e.g., Bandwidth, Done-Done), sinister management-ese (Absenteeism, Clockless Worker), and obsolete yet revealing labor-related terms (After-Dinner Man, Hireling). The authors of The Wage Slave’s Glossary, who in 2008 published The Idler’s Glossary, recently exchanged a few thoughts about the themes of these books.

JOSHUA GLENN: In the Labor Day-themed issue of The New York Times’ Sunday Review, former US secretary of labor Robert B. Reich urged policy makers to boost the purchasing power of the middle class by improving public schools and public transportation, expanding access to early childhood education and higher education, maintaining strong labor unions, enlarging safety nets, requiring big companies to pay severance to American workers they let go and train them for new jobs, pegging the minimum wage at half the median wage, raising taxes on the rich and lowering taxes on the poor, and in general spreading the gains of globalization and technological change more equitably.

Compared with the Tea Party-goaded Republican economic agenda, Reich’s (slightly left-of-center) neoliberal vision of the good life is progressive, even pie-in-the-sky. But our two books refute the proposition that boosting the purchasing power of the middle class will make America, as Reich argues, “a land in which life should be better and richer and fuller for everyone.” (As the child and sibling and husband of progressives, this makes me feel rather like an enemy of the people.) Instead, we seek to defend, as you write in the WSG, “an idea of life free from the depredations of getting and spending, labour and its sale” — whether in the US, Canada, or anywhere else in the world.

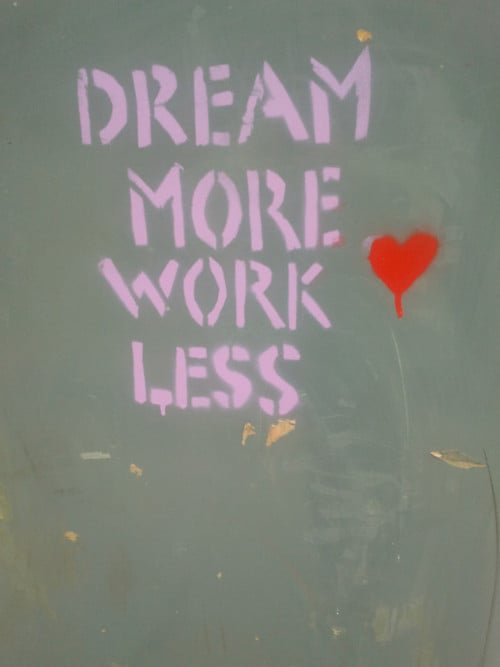

Though we purposely don’t offer a blueprint of a better, richer, fuller life for all, our two little books are nevertheless deeply idealistic. Although we might agree with what passes for progressive political thought today about, say, the importance of improving public schools and public transportation, enlarging safety nets, and various other particulars, we disagree with the notion — taken for granted by Republicans and Democrats, Conservatives and Liberals — that free markets, free trade, and the unrestricted flow of capital are key to producing the greatest social, political and economic good. And we disagree with the notion, taken for granted by everyone, that the more we work, the better off we’ll be. Ours is an idler idealism: we demand not strong labor unions, higher minimum wage, or lower taxes, but freedom. Or, better: FREEDOM!

Does that make us enemies of the people?

MARK KINGWELL: I think it makes us anarchists as opposed to socialists. Though I do sometimes describe my own politics as democratic-socialist, there is an increasingly stark division between those who think boosting productivity and creating more jobs are the only solutions to current ills and those, like us, who think the model is so broken that this sort of fix will just extend the troubles. We’re really saying that everyone needs to rethink their own ideas about life, rather than just trying harder and harder to buy in to a system we know is unjust and, massively evident since 2008, dysfunctional. I think I say somewhere in the introduction to the Wage Slave’s Glossary — don’t change the system, change yourself! Or as you put it: FREEDOM!

The key to this, as we suggest, is language. What anthropologists call the language upgrade allowed evolving humans to make a huge leap in their ability to coordinate actions and achieve things. Language is the key to civilization as we know it. But language is supple. It can be turned and twisted to bad purposes, it can be used to manipulate, coerce and deceive. The premise of both our books, but especially The Wage Slave’s Glossary, is that ideas creep into consciousness, take up residence there, and influence behavior in large measure through vocabulary. How we think about work and how we talk about it are inextricable. What I call the work-idea — the presupposition that everyone must work, and that work will set you free — is one of the largest and most successful ideological deceptions in human history. To the extent that ‘everyone thinks this’, it seems beyond challenge. But we’re trying to subvert that ideology, and doing so obliquely with a book-form that is not usually considered critical or political at all, the ‘mere’ glossary.

This idea that work is not the key to human happiness is a more radical message than anything to be heard in the mainstream political discourse, yes, and that will make it seem kooky to some. And we never want to stop being playful about the ways we deliver the message. But the serious part is the age-old philosophical demand, the duty to examine your one and only life. And then — well, I suppose our book is not quite as beautiful as the Archaic Torso of Apollo (though with Seth’s wonderful art it’s pretty darn beautiful) but its ultimate demand is the same as the one Rilke saw in all great art: You must change your life!

GLENN: Amen to rethinking today’s taken-for-granted, supposedly commonsensical notions about work, life, and everything else — via analysis of the language in which those notions are expressed. However, it’s important to point out that both my glossary and your introduction look not only at current workplace slang and management-ese, but also at obsolete notions.

The commercially viable thing to do, for this book, would have been to restrict our purview to the present moment — which is the only moment that anyone is ever encouraged to think about — by poking fun at contemporary workplace jargon. Yet because you and I are interested not only in philosophy but history (intellectual history, or history of ideas, in particular) we ask questions like, “How did the organization of work, and the ‘work idea’ as we know it, come to seem natural, eternal, and inevitable… when they are none of the above?”

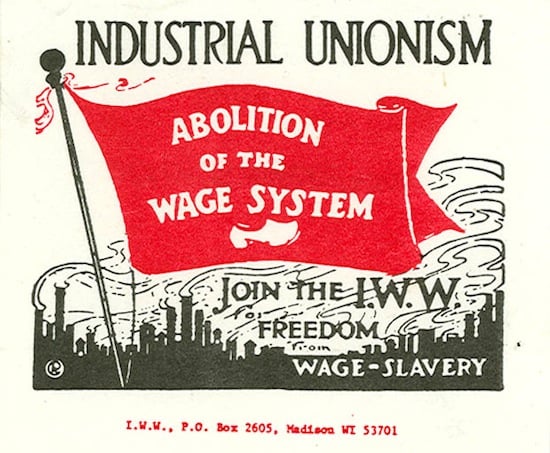

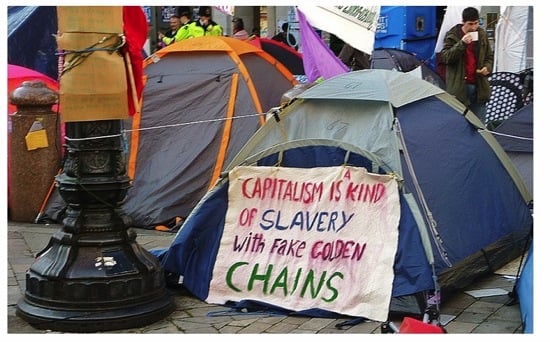

Asking that question sent me back to the early to mid-19th century, an era during which the artisan tradition (in which workers themselves made decisions about how and when to do their work) was replaced by a system of work which first appeared on colonial plantations. This new system demanded — and continues to demand — that workers rent themselves, i.e., to be used by a boss, who in exchange for paying them wages is permitted to dictate the terms of their work. To artisans, yeoman farmers, and other independent-minded people in those early days of industrial capitalism, wage work seemed like an insidious form of prostitution or even slavery — which is where our controversial title phrase “Wage Slave” comes from.

Whether we’re blue- or white-collar, labor or management, 99% of us are deprived on a daily basis of the opportunity to conceive of ourselves as authors of our own destinies, deciders of our own actions. We’re told not only what to do, but how and when to do it. What’s worse, the current work system has come to seem natural, inevitable, and eternal; in part, this is because we’ve been encouraged to believe in a “work idea” which insists that anyone who resists the work system is a slacker, a loser, a failure. To the Lowell Mill Girls who coined the term “wage slavery,” this is an intolerable state of affairs. We were not put on this planet to be bossed around, that was their position, and it’s one that I embrace.

But critics of the term “wage slavery” then and now claim that it’s an inaccurate and offensive notion. Chattel slavery is a violation of human rights, they say; working for a wage is something that you decide to do of your own free will. Free will — that gets us into deep philosophical waters.

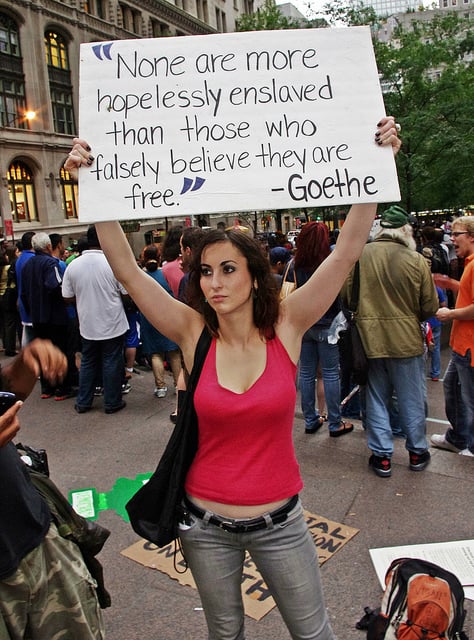

KINGWELL: I’m sure you remember a great image from the Occupy Wall Street protests, of a young woman holding up a sign with this quotation from Goethe: “None are more hopelessly enslaved than those who falsely believe they are free.”

Philosophers, and poets too, have long been in the business of trying to show people that they can be mistaken about their desires, or mistaken about what is in their actual best interests. In general terms we can call this the critique of ideology, and I associate the very idea of wage slavery with this critique. Of course wage slavery is not the same as chattel slavery, which is emphatically worse and indeed evil; but there is an important sense in which we are capable of enslaving ourselves — in bad relationships, in harmful addictions, in cycles of abuse and self-denigration. Wage slavery gets at this perverse aspect of the human soul: an ostensibly voluntary arrangement, such as accepting a job when the alternative is the hardship, and perceived shame, of unemployment, can seem like a free act. But if the job then works to limit your possibilities, or channels all your energy into something you find meaningless — or, worse, invades your leisure or forces you to spend money in the great company store of consumer culture — well, then maybe that is validly labelled a kind of slavery.

Of course, critics of Ideologiekritik can always push back and say, “Come on, aren’t you being paternalistic and condescending, pretending you know more about what’s good for me than I know myself?” It’s a good question, and one of the many things I favour in our oblique approach is that we don’t insist, like Rousseau or Plato, that we know what the correct answer is about human freedom. Nor are we anti-job. If you love your job, if it fulfills you and gives your life direction and meaning, well, mazel tov. But if, like so many people, you find the insistence on work troubling, if you would prefer not to be defined by how you earn a living — “So, what do you do?” is the most common question among us these days — then perhaps it’s time to re-think the presumptive commitment to what I call in the introduction ‘the work idea’.

If nothing else, just exploring the language of the work idea is a liberating stroll in the history of ideas, as you note. Such a stroll has a deep purpose, whether or not one endorses the idea of wage slavery: it makes you ask yourself, in the best philosophical sense, what you think you are up to. What is life for? What are my true desires, and how can I pursue them? Is there really any happiness to be found in upgrading my cellphone, amassing more tokens than the next guy, or raising ‘productivity’? Old questions, profound questions, human questions.

Are we free? Well, maybe. You tell me. But please, think about it first. That is all our little book desires to say — but it’s a lot!