Early ’60s Horror (5)

By:

December 23, 2011

[Fifth in a series of posts by David Smay on horror movies of the early 1960s.]

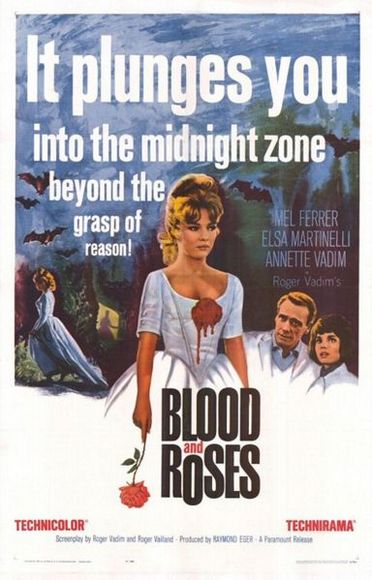

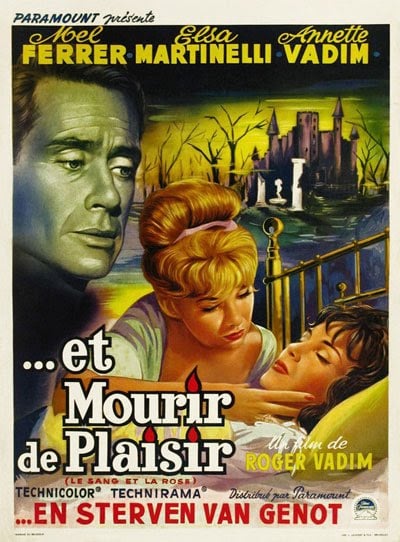

Nobody’s really seen Blood and Roses (d. Roger Vadim, 1960). They think they might have seen it because they know the song by The Smithereens, or they’ve confused it with one of Hammer’s Karnstein trilogy which also derive from Sheridan Le Fanu’s Carmilla. It’s never been released on DVD, and even the few folks who’ve watched the VHS tape released in the States have watched a print that’s both cropped and so badly washed out you could forget the movie is in color, much less Technicolor.

This used to be standard for horror movies. Stephen King’s pre-VCR era Danse Macabre depends on the folklore of horror movie fandom to recall Freaks when it was presumed that all original prints had been lost, and Cat People and Eyes Without a Face existed more as elusive legends than films. In the time that it takes you to type “blood and roses part 1” into Google you could watch a version of the film on your iPhone, but it’s a shadow of Vadim’s original. As a consequence you don’t just watch Blood and Roses, you concurrently fill in the movie that you’re missing, the one with vivid colors and wide screen in French. It’s not unlike a Classics scholar trying to expand on Menander from half a speech or digging through the shards of Sappho’s poetry.

Blood and Roses shares plot elements with Bava’s Black Sunday. Both feature cursed crypts which are disturbed so that a young woman is possessed by an evil, ancestral spirit. This notion of the transmigration of the soul is different from that of possession, when a demon might temporarily control you. In transmigration the invading spirit destroys the original soul of the body it inhabits, and like the recurring facial mutilation motif seen in these early 1960s horror movies, it literalizes a metaphor for loss of self. Corman’s Poe movies return to this theme, in Tomb of Ligeia (1964) and The Haunted Palace (1963) (which, despite getting its title from one of Poe’s poems, is actually based on H.P. Lovecraft’s “The Case of Charles Dexter Ward”).

Despite the lesbian vampire plotline from Le Fanu, and even the country estate setting Blood and Roses sets itself apart from the gothic of Black Sunday, Hammer’s The Brides of Dracula, or Corman’s The House of Usher (all from 1960). The movie opens with a jet taking off and establishes itself in our sub-genre of Liminal Horror with Carmilla as the neurotic/hysteric, suggesting that her possession by Millarca may be a psychotic break. There’s even the over-explaining doctor to give a quick Freudian précis of her condition, an expositional tic you see a lot in this era (most famously in Psycho). This cultivation of the French Fantastique is more apparent in the original than the American translation where the expository voice-over makes explicit her possession. Still Annette Vadim plays Carmilla with the same high-strung vulnerability we see in Julie Harris’ Nell from The Haunting or that Deborah Kerr brings to her performance in The Innocents. As with those characters, Carmilla’s love for her cousin Leopoldo is forbidden, so her madness is linked to thwarted desire.

There’s ambivalence about the portrayal of female sexuality in this cycle of movies. Most obviously you see reactionary horror as a woman’s sex drive is literally seen as monstrous. But these movies also create a narrative space that explores a woman’s desire, where it’s shown sympathetically (though it is still seen as problematic). All the cultural anxiety that followed in the wake of The Pill finds expression here. If women can safely have sex outside of marriage or reproduction then they are dangerous, but that sexuality is rightly tied with identity and growth, and men constantly seek to thwart and control. That’s right — I’m arguing there’s a feminist critique in a lesbian vampire movie by a notorious sexploitation director.

Vadim’s reputation as a sleazy Zalman King, Red Shoe Diaries, softcore filmmaker (not entirely undeserved after launching Bridget Bardot in And God Created Woman and embarrassing Jane Fonda’s feminist years with Barbarella) obscures his genuine talents as a filmmaker. He gets no respect (it probably doesn’t help that the original French title was Et Mourir de Plaisir — And To Die of Pleasure?) but Blood and Roses moves with a languid, assured pace and features several set piece scenes that are masterful. It just gets stranger and stranger as the movie progresses. Most famously, the scene where Carmilla enters Georgia’s mind is presented as a Cocteau influenced dream sequence that is as unnerving in its way as the face transplant scene in Eyes Without a Face. It’s Felliniesque before Fellini himself started to earn his adjectival status. Here is a clip of the dream sequence:

To get back to the plot, the spirit of her vampiric ancestor, Millarca, possesses the soul of Carmilla (or so Carmilla believes). Carmilla then begins to stalk the countryside, killing a young servant girl. Carmilla loves her cousin Leopoldo, but his engagement to Georgia pushes her over the edge. Carmilla seduces her cousin, and then seduces his fiancée. Transgressions galore! The scene where Carmilla and Georgia are trapped in a greenhouse during a storm is charged with incredible erotic tension. Unable to stop the wedding, Carmilla goes to Georgia in the night and effects one last transmigration. Carmilla dies, falling on a stake, but the transferrence is complete — and the spirit of Millarca possesses that of Georgia. Sexy sexy transgressive euro-Evil wins!

If ever there was a movie begging for a Criterion edition, this is it; a restored version of Blood and Roses would be recognized as a masterpiece. Like Eyes Without a Face this movie draws heavily on Cocteau to create its dreamlike and tragic atmosphere, helped tremendously by Claude Renoir’s cinematography and Jean Prodromides’s lush score. In my next installment I’ll examine The Innocents in conjunction with the recently released (on DVD) Burn, Witch, Burn. Two of the very best film adaptations of two of the most influential horror stories.

MORE HORROR ON HILOBROW: Early ’60s Horror, a series by David Smay | Phone Horror, a series by Devin McKinney | Philip Stone’s Hat-Trick | Shocking Blocking: Candyman | Shocking Blocking: A Bucket of Blood | Kenneth Anger | Sax Rohmer | August Derleth | Edgar Ulmer | Vincent Price | Max von Sydow | Lon Chaney Sr. | James Whale | Wes Craven | Roman Polanski | Ed Wood | John Carpenter | George A. Romero | David Cronenberg | Roger Corman | Georges Franju | Shirley Jackson | Jacques Tourneur | Ray Bradbury | Edgar Allan Poe | Algernon Blackwood | H.P. Lovecraft | Clark Ashton Smith | Gaston Leroux |

OTHER HILOBROW SERIES: FITTING SHOES — famous literary footwear | POP ARCANA — spelunking weird culture | SHOCKING BLOCKING — cinematic blocking