Spoiler Alert: Shock The Monkeys

By:

December 7, 2011

Caveat lector: may contain spoilers.

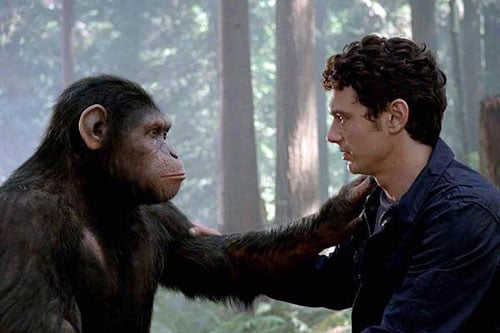

Rise of the Planet of the Apes, dir Rupert Wyatt, 2011.

Imagine if you will, a point in the not-too-distant future where high-stakes research has produced a genetic therapy to repair neuronal pathways lost during Alzheimer’s. The delivery mechanism is a denatured virus that can penetrate otherwise resistant cell walls. Imagine further that this therapy has been so effective that it is ready to undergo human trials. Or perhaps not quite ready, but it has performed spectacularly well on chimps, our closest biological relatives. Imagine further, that you are the head researcher, and that it is your own father that has Alzheimer’s. Might you be inclined to do a little fieldwork at home…?

Imagine, in other words, that you are James Franco, who in the not-too-distant future will apparently play each of us in turn.

Early in the film, the lab’s showcase chimp, an adult female put through increasingly challenging IQ paces with some geometric puzzle-solving, goes completely berserk just as she is supposed to demonstrate her enhanced mental powers to the committee. Her explosion of violence causes a lab shutdown, a funding shutdown, and the forcible shutdown (extermination) of her and all her fellow research subjects. Except for one. The animal handler refuses to euthanize her newly born (and somehow previously concealed) baby, leaving the syringe for Rodman (Franco) to do the deed. Regarding the tiny chimp, Rodman realizes that it might have been simple maternal instinct rather than a side effect of the drug that caused the destructive behavior. He decides to bring the chimp home. Just for a little while. Maybe it will calm his dad down, to have a little pet. Dad (John Lithgow), abilities much diminished by aggressive Alzheimer’s, delightedly names the chimp Caesar.

Monitoring Caesar’s growth (and giving him a Spielbergian dream room in the attic), Rodman avoids reinstitutionalizing Caesar, realizing that the genetic improvements in Caesar’s mother have been transmitted to her son. And, and a last-ditch attempt to avoid institutionalizing his father for Alzheimer’s, he gives him the drug, too. Improvements are immediate. At first.

This prequel is a sensitive continuation of the late 60s/early 70s-era Planet of the Apes films, which featured Charlton Heston as the temporally stranded, loincloth-draped astronaut, and Roddy McDowell as the rubberized Ape. Hugely popular at the time, the outdated special effects and clunky dialogue of the original Apes films has made them prime candidates for satire, cult status, and guilty pleasure. But Rise does more than just offer improved special effects for the franchise; it sets itself to imagine how, exactly, might this possible future arrive? And (with a little help from Twelve Monkeys and The Hot Zone), we see that as a possible future, it is not that divergent a timeline from ours. In fact, there’s a real possibility it may not be divergent at all.

Starring the unnervingly malleable Andy Serkis as the CGI’d Caesar, Rise traces an increasingly desperate endgame in the Bay Area, with a post-Vertigo San Francisco serving as the deceptively lovely dystopia. Caesar’s mental development requires increasing emotional sophistication, as he is taken from the homeland security of his suburban room and thrown in amongst his own kind in an Ape holding facility near Richmond, CA, complete with cells, overcrowding, power struggles, and blatant cruelty. The questions of “What Am I?” and “What Can I Be?” are accompanied by the increasingly fraught, and increasingly relevant, “How Should I Be?”

What models does Caesar have? Some humans have treated him well. Other humans have not. Human institutions, moreover, have killed his family and raised him to be expendable. Is he a pet, an animal, a little brother, a medical experiment, a thing? Should he submit? Escape? Or…enact what would certainly be, from his perspective, a just revenge? Were the new neural connections spawned by the genetic therapy merely cold leaps in logic, or did they also enhance the potential for moral capacity? What becomes of right and wrong when we play God?

Because when we say we “repair” or “re-grow” the cells destroyed in Alzheimer’s, we really just mean grow. The destroyed cells are gone. New ones take their place. And those new ones might, given different circumstances, encode different intellectual and behavioral pathways. Caesar’s circumstances are about as different as they can get.

That’s on the Apes’ side of things. Back with the humans, it might be worth considering just how denatured that delivery virus actually is. In the research lab, time has not stood still. The genetic treatment has advanced from injectable to aerosol, while Rodman’s father, despite continued genetic therapy, has started another downward slide, as the experimental therapy reveals its limitations. Here the film reveals the influence of a different narrative: while the beginning of Flowers for Algernon is enacted by the Ape, the end may in fact be ritualized by Man.

An object in motion tends to stay in motion, and Caesar is the object in question. It’s just a movie. But the not-too-distant future in the mirror world may be closer than we think.

Project Nim, dir. James Marsh, 2011.

What we have here is a failure to communicate.

Or, do we?

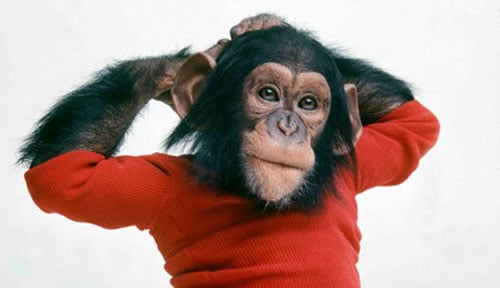

The documentary Project Nim reexamines the well-publicized attempt by Professor Herbert Terrace, a behavioral psychologist at Columbia University, to test whether we can talk to the animals. Nim Chimpsky, his name a play on the linguist Noam Chomsky, would be taken into a human home and raised as one of the family, exposed to all human forms of communication, verbal and nonverbal, while being taught sign language.

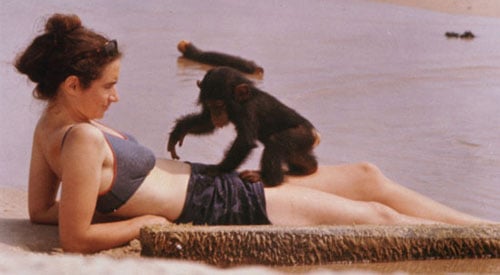

The LaFarges were a hippie-bookish blend of kids, dogs and the usual controlled chaos of domesticity. Mom was an ex-student of the professor, as well as an ex-student-affair. No one in the family knew sign language. Mature chimps are aggressive and not shy of biting; an adult male chimp can weigh 150 pounds and be over 5 feet in length.

But baby chimps are cute! And it was the seventies. What could possibly go wrong?

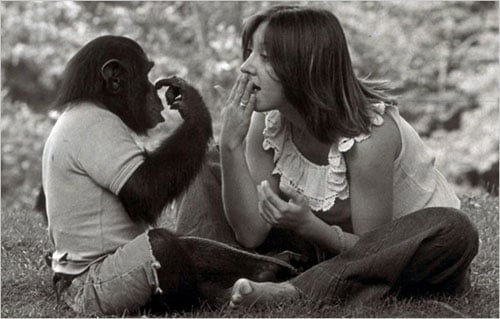

Nim communicates to us clearly in every frame he is in. Always with body language and vocalizations, but very often he communicates with sign language, the bridge between him and those who would use or understand him. Because Nim did learn sign language, in fact, like Washoe before him, he acquired a significant vocabulary.

But that, it turns out, was not enough to answer the question; can we talk to the animals? The answer is yes, to some of them, to some extent. But what is that extent? Did Nim use sign language to say what he was thinking? Or did he, in the revised opinion of the original researcher, simply memorize what sequence of gestures would get him what he wanted: food, toys, companionship?

Despite advocates of dolphins, dogs and horses, chimps are our best bet for interspecies communication. Sharing approximately 96% of our DNA, they also share opposable thumbs, a social, tool-using, hierarchical society, and an adolescence that allows for further brain development. However, their brains are significantly smaller than ours, their adolescence relatively compressed, and it is not clear our cousins are simply a bit behind us on the evolutionary tree, rather than on a nearby, but divergent, branch of their own.

Nim’s story begins with the type of well-meaning violence we expect to foreshadow a horrific conclusion. In 1973, Terrace and Stephanie LaFarge visit the Institute for Primate Studies in Oklahoma. Nim’s mother is shot with a tranquilizer gun while breast-feeding and LaFarge is pushed in to snatch the baby, in an operation that feels more robbery gone wrong than research experiment. Nim is brought home to New York, played with, breast-fed!, and filmed.

A new student, Laura-Ann Petitto, appears on the scene, enthusiastic about the project and the professor. She designs and implements a course of study and a practice of notation and recording, extracting actual data, and significant progress from Nim. And significant attention from the professor. She is 18.

Nim is then removed from the family home, another furtive, traumatic separation, and relocated with several student researchers to Delafield, a Columbia-owned mansion in Riverdale just north of New York City. The extensive grounds provide space for Nim to grow and experiment, and the extensive building can house the growing number of student assistants. Nim’s progress, in terms of vocabulary acquisition, continues to arc skywards.

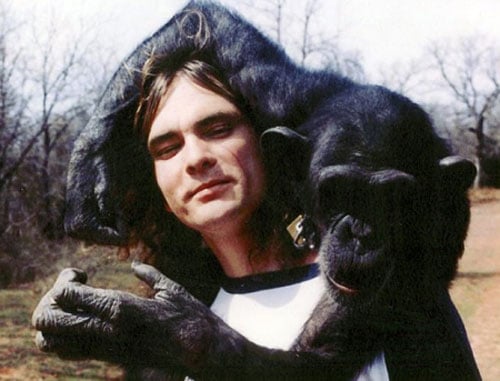

One thing the viewer notices about chimps is how physical they are, especially when young. The young literally hang on their mothers’ fur, and Nim is no different. He is all over the researchers all the time, wrestling and playing and climbing and snuggling. One realizes that it may be difficult, if not impossible, to maintain critical distance in an experiment of this kind.

But Nim is growing, reaching his mature strength and size. Toilet training is attempted, as reapplying his diapers is becoming unfeasible. The combination of his teeth and size, as well as his maturing aggressive tendencies, is a crucial turning point in the experiment. In fact, it is the official end of the experiment. Terrace decides to call it off and transfer Nim back to The Institute in Oklahoma where he was born, and where he will be with his own kind. Nim… has never really been with his own kind. A third brutal separation is enforced. The Institute has cages, and bars.

But the Institute also has sympathetic researchers, and Nim does begin to socialize with them, as well as with some other chimps. And there are extensive grounds where Nim can range and explore. Being social, Nim develops strong relationships in his new location, especially with Bob Ingersoll, who becomes his closest friend and champion.

But the Institute, run by the University of Oklahoma, suffers a funding cut. Many of the chimps, including Nim, are sent to LEMSIP, a medical research facility run by NYU.

The story does not end there. There is a court case (at which Nim was scheduled to be called as a witness), there were other keepers and other animals, there was a mate, there was a problematic reunion, and there was a well-deserved reunion. Nim’s language skills were declared a Skinneresque breakthrough by Terrace, and then reinterpreted and recanted years later. Nim died in 2000 of a heart attack. He was 26.

One’s sympathies ebb and flow widely over the course of the film, as good and bad resist easy assignment, and every silver lining reveals its touch of grey. Even Nim is the nexus of changing sympathies. Over the course of his life Nim grows into a character as complex and fascinating as anyone who ever deserved a biopic.

Nim was not human, and did not become so. But as the documentary shows, he is no less worthy of our empathy, interest and care. His life in the wild would not have been easy; his life with us was in many ways less easy still. But we can say of Nim; that if he lacked liberty, here at least was life, love, and the pursuit, if not always the attainment, of happiness.

And in this, he was exactly like us.

Versions of these essays (Rise) (Nim) appeared on the Brattle Theater Film Blog, October 2011.

Read more Spoiler Alerts.