Beardless in Barnesville

By:

November 29, 2011

[This essay first appeared in the July-August 1996 issue of Utne Reader.]

As I pulled up in my rented car to the historic red brick house in Barnesville, Ohio, on April 13 for the portentously titled Second Luddite Congress, my expectations weren’t very high. After all, the only neo-Luddites I’d ever run across were either publicity-seeking intellectuals who typed their pro-simplicity manifestos on laptop computers as they jetted from one conference to the next or fumble-fingered technophobes enraged by the complexity of their digital watches. And, of course, seeing the mug of Unabomber suspect and neo-Luddite legend Ted Kaczynski plastered on newspapers everywhere and having to listen endlessly to Weird Al Yankovic’s spoof “Amish Paradise,” which was in heavy rotation on the radio, wasn’t helping. Every stinky back-to-the-lander in the country is going to be here I thought as I rounded the corner of the building… and froze, stymied by a vista that confirmed my worst fears.

My God, what an unruly collection of beards! Ratty Quest for Fire beards, free-flowing Deadhead beards, tousled Walt Whitman beards, kooky Kaczynski beards, hipster goatees circa San Francisco 1958, and dozens of untrimmed, Quaker “peace” beards affected by the most studiously “plain” folk in the crowd. Also, everyone — from the punk who was so pierced he seemed perforated to the serenely bonneted Quaker women — was wearing those little round John Lennon glasses, not to mention a depressingly practical assortment of hike-the-Appalachian-Trail-and-construct-a-cow-barn-in-your-spare-time shoes. My own urban-chic, hopelessly ironic look — smooth chin, Malcolm X tortoise-shell glasses, bilious maroon suede Converse All-Stars — was out of place here. I had seen neo-Luddite utopia, and it was sensibly shod, nearsighted, and hirsute.

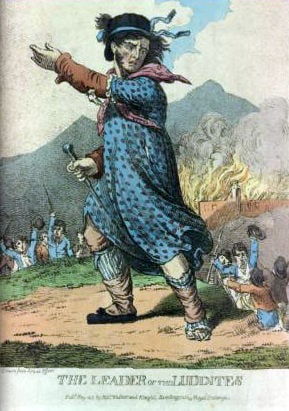

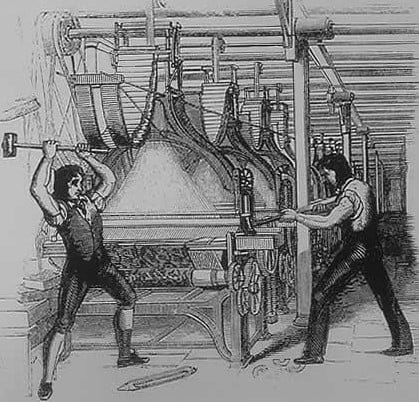

All the beards had gathered in Barnesville to lay the framework for the congress itself, which would convene two days later — exactly 184 years to the day after the original Luddites, a ragtag band of weavers and artisans who tried unsuccessfully to undermine the Industrial Revolution, held their first and only convention in Nottinghamshire, England. The purpose of the second congress, which was being sponsored by the publishers of the pro-simplicity Plain magazine, was to come up with the neo-Luddite Statement of Means, a manifesto on how to reduce the overwhelming power of technology over our lives.

In general, I was surprised by how commonsensical and moving the opening session’s speeches were, but as the participants began to respond, it seemed that everybody had an ax to grind. The audience grilled self-appointed neo-Luddite spokesman Kirkpatrick Sale about which machines he’d used to write and publish his books, challenged bioregionalist author Stephanie Mills and Thoreauvian farmer-essayist Gene Logsdon on whether just living off one’s own land is enough, and excoriated writers David Kline and Art Gish, who live in “plain” Christian communities, for the perceived sexism and exclusivity of their lifestyles. Agnostics grumbled at the Christian rhetoric of some of the speakers (mild though it was); political activists mocked do-it-yourselfers; and city dwellers scoffed at farmers. Only midwife Judy Luce, publisher Bill Henderson, and the Internet-skeptical physicist Clifford Stoll escaped attack, but that may have been because they all spoke just before the breaks. The fact that four of the morning session’s five male speakers wore beards — three of them peace beards — left me wondering whether I was just being brainwashed.

At dinner that evening, after chatting with a Philadelphia man who encourages religious congregations to “anoint the boiler” of their place of worship (in an effort to promote energy consciousness), I decided that, despite some obvious ideological differences, there was one thing that united everyone in the building: fear of hypocrisy. Apparently, we had all internalized the prevailing cultural attitude that it is selling out to voice even the slightest concern about the encroachment of technology without simultaneously having your electricity shut off. (This point of view is eloquently demonstrated by the mainstream media coverage of the congress, by the way.) Everybody seemed to be eyeing his or her neighbor’s Simple® brand clogs and thinking, “Well, how did you get here, Mister Luddier-than-Thou? Walk? I don’t think so!”

But a mutual edginess about the H-word is not enough to unite a movement. How on earth were all these prickly individualists supposed to arrive at a single Statement of Means? The congress, like almost every other activist event I’ve ever attended, seemed futile, and I began to long for my hotel room back in Wheeling, West Virginia, and the TV with unlimited cable channels.

Just before we broke for the evening, author Bill McKibben urged us all to go back to our hotel rooms and hang a cover over the television. “The only subversive thing you can do in a society without limits is to have more fun than everybody else,” he insisted, to a great deal of applause. “And whatever the purpose of human life may be, it can’t be channel surfing!”

Later, as I watched a couple hours of I Love Lucy reruns on Nickelodeon, I wondered if a TV-less revolution based on self-restraint, spirituality, and fun might just be feasible. But then that great episode in which Tallulah Bankhead moves next door to the Ricardos, and Lucy makes Fred and Ethel pretend they’re her servants, came on, and…

Next morning, I was ready to get out into the bright spring air of Wheeling, an old mining town I’d been dying to explore. But I couldn’t help noticing that A Change of Habit — an Elvis movie which I’d probably already seen 15 times — was just starting on the Movie Channel, so I spent the entire morning sitting around the hotel room swilling a Mountain Dew “Big Slam” and rooting for Mary Tyler Moore to pick the swingin’ inner-city doctor over Jesus Christ. By the time I screeched onto the meeting house lawn at 1:00, just in time to wolf down a turkey sandwich, Scott Savage, the editor of Plain, was about to take the stage. This was the first time I’d ever laid eyes on the man, even though I had talked to him on the phone several times. In fact, it was Scott who persuaded me to attend the conference, not so much with his agenda but with the serene and good-hearted way he assured me that we needed to speak face to face.

As he took the podium, he was dressed in a sober black suit, a farmer’s straw hat, and — yes — John Lennon glasses. “Although Quaker Friends have historically been very active in issues ranging from abolition to the status of women, they have always done the opposite of the activist model,” he began with a sly smile. “Friends use the ‘technology’ of sitting, the ‘dialectic’ of waiting, and the ‘activist platform’ of listening. This is the country of the disembodied brain, and a Quaker-style meeting this morning may be able to help us come back to our bodies. So sit close together.”

Warm laughter greeted Scott’s words. There was something so intriguing about this middle-aged man with cherubic features and a flyaway peace beard devilishly baiting activists, New Agers, simplicity-craving yuppies, and the press in a strange mix of pop culture-speak and humble Christian piety. I knew he was a person deeply concerned with technology, not in the abstract, but how it directly affects his family. Every time we spoke on the phone, it seemed, he had just rid himself of another modern convenience that I considered indispensable: his television, his computer, his car. The day after the conference, I later learned, he even moved the telephone out to the barn, with his new horse and buggy.

After Scott finished talking, everyone sat quietly for the next two hours watching sleepy wasps bang against the tall windows of the meeting house, trying not to speak unless we were prompted to do so by something beyond our egos, and struggling to have faith in one another. Although some people did get up, on occasion, to voice their concerns about conflicts that had arisen the day before, the fact that no one was refuting anyone else, and that there were long stretches of contemplative silence, led me to see that this — not the speeches or the debates — was the reason we’d been brought together.

After that interlude, many participants began to drop their agendas and make practical suggestions for nonviolent resistance to technology: “Don’t buy anything, anything,” said one man, “unless you call up the company that made it and ask ‘What are the working conditions for the people who assembled this? How were natural resources used in its manufacture? How long will it last? And can I maintain it myself?’”

“Let’s get rid of streetlights,” piped up the Philadelphia man. “Stop signs are safer for a community because they force people to use their judgment; streetlights just encourage us to drive faster.”

“Young people should create a scene where it’s cool to be plain,” suggested an Urban Outfitters-clad teenager. “Punks already have their vegan scenes and their straight-edge scenes. How about an anti-technology scene?” Visions of “plaincore” bands — sans amplifiers — screeching Lutheran hymns in dingy clubs danced in my head.

That evening, Savage and McKibben both told inspiring stories and then counseled everyone to stop looking for institutional or technological fixes and to use the imagination as a subversive weapon. At the end of the day, the delegates gathered in the kitchen to put together a rough draft of the Statement of Means. I stuck around, hoping — as I imagined journalists were supposed to — that I’d catch a glimpse of the real neo-Luddites, unmasked at last: Stephanie Mills and Charles Siegel and Kirkpatrick Sale grimly battling for control of the document. Oddly enough, the delegates turned out to be a uniformly decent and deeply conscientious bunch who put together the draft without any problems. No story here, I thought.

That night at the hotel, still under the neo-Luddites’ spell, I hung my jacket over the television and started reading a Jules Verne novel I’d picked up in Barnesville. Over the next couple of hours, no matter how often my hand involuntarily snatched the TV remote control and my thumb stabbed at the power button, it was to no avail.

The book, Five Weeks in a Balloon, which Verne wrote in 1862, 50 years after the original Luddite uprising, included a character who prophesied that “if men go on inventing machinery, they’ll end by being swallowed up in their own machine. I’ve always thought that the last day would be brought about by some colossal boiler, heated to three thousand atmospheres, blowing up the world.”

The next morning I eluded the TV without much difficulty, and made it to the meeting house before anyone else. Strolling around the campus of the nearby Quaker school, I bumped into Savage, and we finally had our face-to-face conversation. I told him that many of the ideas I’d heard reminded me of Abbie Hoffman’s irreverent, counterintuitive brand of revolution, and Scott proved to have a thorough understanding of Yippie tactics. “Part of the reason those guys used so much obscenity,” he said, “was that they were deeply concerned about the power of big business and the media to co-opt the trappings of any anti-establishment movement. They figured that curse words, at least, couldn’t be sold back to them. That’s part of what’s so subversive about simplicity. You can’t sell it!” I didn’t have the heart to tell him what was really happening in the world of commerce. All of a sudden, thanks in part to the neo-Luddites, plain is hot. (But he probably knew that.)

As it turned out, the Big Event was anticlimactic. Despite some disagreement over the language — loaded terms such as guilty, nonviolence, and even family raised hackles, for instance — the assembly seemed to agree more than it disagreed. Cheers went up when the clerk of the meetinghouse read the final Statement of Means — which included entries such as “We believe that the needs of people exceed the needs of the machines” and “We affirm the importance of… times of rest, times of fasting from production and consumption; time spent in solitude, listening and waiting.”

In my mind, however, the real business of the congress had already happened the day before. There we’d been: Mennonite farmers, professional agitators, pagan grandmothers, journalists, and lots of ordinary folks, squeezed together onto narrow wooden benches without the mediation of technology, practicing self-moderation and pacifism and building some kind of funky, diverse — if temporary — community in the process. Later, as I rushed back to the airport in Pittsburgh, struggling most of the way with my car’s power windows, and reflected on what had transpired, it struck me that when we followed the example of the Quakers, whose meetings are about joy and trust as opposed to politics, we had, in a small way, already succeeded in our purpose. We had shown that doing less, which seems so un-American, was an essential “means” to overcoming the most out-of-control, damaging technology of all: the complicated circuitry of the self.

READ MORE essays by Joshua Glenn, originally published in: THE BAFFLER | BOSTON GLOBE IDEAS | BRAINIAC | CABINET | FEED | HERMENAUT | HILOBROW | HILOBROW: GENERATIONS | HILOBROW: RADIUM AGE SCIENCE FICTION | HILOBROW: SHOCKING BLOCKING | THE IDLER | IO9 | N+1 | NEW YORK TIMES BOOK REVIEW | SEMIONAUT | SLATE

Joshua Glenn’s books include UNBORED: THE ESSENTIAL FIELD GUIDE TO SERIOUS FUN (with Elizabeth Foy Larsen); and SIGNIFICANT OBJECTS: 100 EXTRAORDINARY STORIES ABOUT ORDINARY THINGS (with Rob Walker).