Burn, Baby, Burn

By:

November 19, 2011

It’s that time of year again. The seasonal shift surfaces a certain kind of music, a certain kind of mood — whether you like it or not, you find yourself compelled and propelled along a well-worn narrative path; that old, old story made new again. You resist, but you know it’s futile, and inevitably, for bad or good, the appointed time arrives.

You know what I’m talking about.

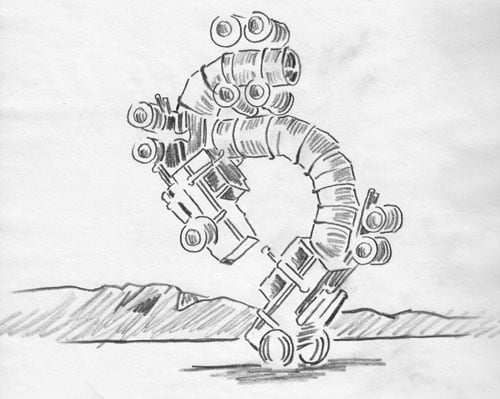

[GypsyDogs]

I’m talking about 287 DAYS UNTIL THE MAN BURNS.

The thing about living mythology is that you don’t choose the one you get. It chooses you. You may prefer, or even attempt to insist upon, Jason and his Argonauts, one-eyed Viking cage fighters, Eric Bana in a toga, Star Trek The Next Next Generation. Midcentury Modern vampires. But your choice is as futile as your predictable resistance. You — we — are immersed in something you may not suspect. This story has already begun.

What’s the buzz? And where? Check the unplanned edges of cities and flows. Check the neglected spaces of your imagination. Bring along your battered copies of the VALIS trilogy, if holding on helps. Because contemporary mythological space might look normal, or look like nothing at all, at first. What it really looks like is overlooked.

Maybe… it looks like a giant party in the desert?

Maybe it looks like hell on earth.

Oh I mean that in all the best, and worst, possible ways.

Earlier this week I spoke with Librettist (and HiLobrow columnist) Erik Davis, and Composer Mark Nichols, about just what they’re up to with How to Survive the Apocalypse: A Burning Opera, a rock opera about Burning Man. After a sold-out run in San Francisco’s Teatro ZinZanni last year, a brand new version of the show, Burning Opera LA, produced by Ghostlight Gypsies, will be performed in Los Angeles on Sunday, November 20, with future shows and versions planned for Reno and beyond.

Erik: Remember how Donny and Marie used to sing, “I’m a little bit country, I’m a little bit rock ‘n roll?” Burning Man is a little bit hippie, and a little bit fucking nihilistic punk rock. I think that explains a lot of the continued appeal. Burning Man is an intensification of a kind of craziness, and has a simultanously revelatory and chaotic character. It’s not a hippie festival, it’s not a back-to-the-land fantasy, so it already has that kind of apocalyptic undertow, back to the post-industrial, punk rock element. By bringing those two things together, in complicated, contradictory ways, it creates a certain kind of resonance that is much greater than if it had been predominantly one or the other.

It’s about free assembly and the American dream and the hippies and the punks and the ravers. People who want to stay up past their bedtime.

Mark: For me it’s not really about Burning Man, it’s more about “California.” Being from Seattle, we see California as very different. And it’s about the wild west and the Merry Pranksters, and the crazy people, and the art, and the idea of civilization, culture, that’s trying to find a beacon. It’s about free assembly and the American dream and the hippies and the punks and the ravers. People who want to stay up past their bedtime. I think people like me in the 80s, felt pretty alone. What I’ve grown to appreciate is how many different types of people are attracted to that.

Erik: The official portrayal of Burning Man from the organization is very much about community, and rebuilding culture and art. But the event is also very much about hedonism. And if that kind of culture has any hope of doing anything that’s going to be anything more than a crazy party, it’s going to come through the crazy party. It’s not going to come in spite of the crazy party, or after transcending the crazy party. That’s not how it works.

But if your quest falls in the desert and there’s no one to hear tell…

Burning Man is a little bit hippie, and a little bit fucking nihilistic punk rock.

Burning Man was like a real live version of the stuff that I used to fantasize about.

What is Burning Man remains a burning question for playa-veterans and never-been’s alike. What kind of art you can make/bring/perform in an alkaline desert miles from the nearest city, a desert that not only lacks water, but lacks insects, scrub brush, cacti, and even rocks, and helpfully supplies in their stead howling sandstorms, debilitating heat, thick, clay-like mud, and a cauldron of interpersonal connection and conflict? But equally significant, and daunting, is what kind of story you can tell afterwards. I have made art at, and for, Burning Man. You may have as well. But what about, “about?”

What’s it all about?

How To Survive the Apocalypse, a Burning Man rock opera, is an attempt at “about.”

Erik: My goal, personally, was that I wanted to write something that could be seen by the burner-curious, or -virgins, even people who have no intention of going, and by people who were jaded, crusty, cynical oldtimers. And that both of them would be moved. So the story had to be accessible enough so that somebody who didn’t know any of the references, any of the allusions, any of the in-jokes, would still be engaged and not feel like they were missing out on anything, but at the same time there had to be enough insider stuff, and enough authenticity, not in factual detail but in spirit, for people who knew the event back in the day.

Then they asked what do you need to write an opera? And I said, I need a philosopher!

Mark: I was walking around the playa with my girlfriend, Julie Lewis, and we heard some people saying “the only art form that can do justice to Burning Man is opera,” and she said, “Well, Mark writes operas…” They kind of flipped out, and brought me back to camp thinking it was some kind of synchronicity. And then they asked what do you need to write an opera? I’d seen a guy speak in a little white tent on the playa about psychedelics a couple of years before, so I said, “I need a philosopher! Like that guy.” And they said, “Oh, that’s Erik Davis.”

Erik: On the playa, everyone’s building worlds. It’s not just that you’re creating a character; your art piece, or your camp, is like a little world. “Where are you? Oh, I’m in some kind of mutant octopoid, satanic temple… I mean WTF is this thing?”

Mark: It’s similar to Hair in that Hair can’t really say too much about hippie culture – it can only present a few people at a time, and then talk about some of the themes that are present in that community. It’s just a little slice of life, really. Our show is not that much of a revelation about all sorts of burners; although we’ve tried, and sometimes it gets closer than others.

But above the multiplicity, there hovers the Ur-myth of the Counterculture: self-selected, you escape from cultural hegemony. Self-selected, you go out into the desert, across the ocean to another continent, across the continent to another city, through cyberspace to the silicon Aridities Beyond. You set up your intentional community and you start to inhabit your Utopia. If the experiment goes well — or even if it goes badly — you attract others.

Is it always the case that there’s just an early scene of avant-garde edge-walkers and they do something really magical, then more people come later and it gets lame?

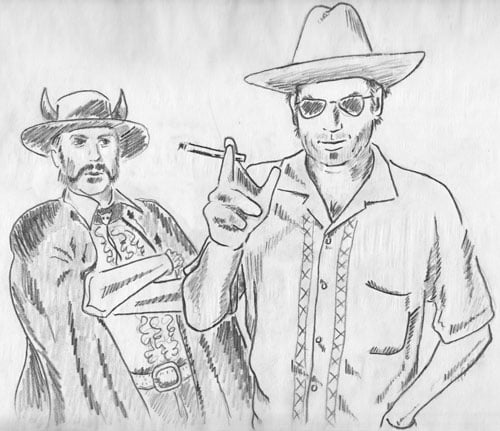

Erik: For me the heart of the show is really the big meta story about the counterculture and the sellout. Is it always the case that there’s just an early scene of avant-garde edge-walkers and they do something really magical, then more people come later and it gets lame? In the show that’s represented by two characters, loosely modeled on Larry Harvey and John Law. Stetson argues we can transform society on a big scale by having this crazy space grow and turn into a city, that whole Larry Harvey visionary thing, which we all respect, in certain ways. But we also give space to the John Law side, which is Mustachio arguing, no it’s lame — it’s too late, it’s too big, it’s just more control; if you want the edge you’ve just gotta keep moving. And I have a lot of respect for that too. I’m kind of a jaded oldster now, “oh, great, more RVsssss…”

[The Clash]

And then, it’s too much. It’s too big, it’s too unmanageable, it’s more strangers than community, it has selected for too many selves. In order to prevent tragedies of various commons, you institutionalize your principles: roads, labels, walls of circled RVs, ticket prices… police. In short, you sell out to the dark god of control.

And at that moment you have mirrored the dominant paradigm, your Utopia has been dys’d; you may as well back out, go back to work; your dreams consigned to the dust-storm of failed experiment, noble or ig-, as was the case.

Something there is that does not love a wall. If you build the wall you’ve already lost.

But no Utopia can be said to be worth its definitional salt if it does not offer hope to all. Changing the World means spreading the Word, means the problem of scale is implicit in the attempt. And besides, Utopia need not equal, and should not equal, encampment. Place is only one aspect of life. If we really offer a moveable feast than not only do we move, but so does the feast, and so does what the feast can offer, and mean. Utopian incursions into the dominant paradigm are of almost infinite variety and scope, and limited only by your imagination. Plus, in the process of building those walls, doesn’t the erection effort construct exactly the kind of commmunity you’ve dreamt of in your philosophies? Maybe we need not so much to run away to the desert, as to bring the desert back?

Erik: The opera contains the Buddenbrooks story of the newbie’s journey — wonderment and weirdness and confusion and the possibility of transformation — woven in with the origin story of the event, which is more about wrestling with issues in underground culture. For me Burning Man is the best countercultural story of the 90s; I wanted to capture that, to write it into the cultural memory. Raves are important too, but they’re not located in a specific place. Burning Man is not only in a place, it’s in such an unusual place, and that characterizes the event. It was important that the desert and the dust were all part of the story we told.

Burning Man is the best countercultural story of the 90s.

Mark: We’ve tried to do parts of the show at Burning Man a few times, but it’s so weird to see a show about Burning Man at Burning Man. People walk by and they go, why are they doing a show about something that’s about 10,000 times bigger than the show, right outside the show? It’s like a puppet show about New York on the streets of New York.

The desert asks nothing of us, that is part of its attraction. But once there, we demand everything of each other. That is part of ours.

Heavy. To balance all this weight, the plot of the opera is relatively and appropriately simple. Two first-timers (the “newbies,” Bud and Brooke) arrive at Burning Man, with different representative aspects of the initial approach.

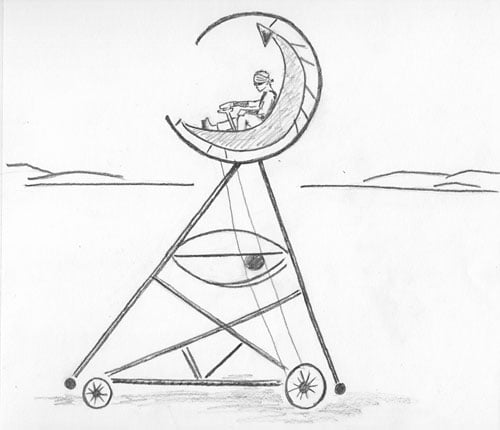

[Newbies, and Burn It Up]

Erik: Bud is Joe Ordinary, he’s not really that hip. He goes to Burning Man because he hears it’s cool, because he knows there are chicks there. It’s a big party, he wants to party, and who can argue with the guy, he’s probably got a crappy job. So he goes to the party and follows his bliss, as Joseph Campbell might say, but his bliss leads him into the abyss. Bud goes through a really hardcore dark night of the soul, and comes out the other side. That’s a very characteristic Burning Man story.

One of my favorite things about the opera and about Burning Man is the process that guys go through when they finally see what I would call more liberated women.

Mark: One of my favorite things about the opera and about Burning Man is the process that guys go through when they finally see what I would call more liberated women. They just don’t know what to do. “Am I supposed to be more outgoing? Am I supposed to be like a pickup artist? I don’t know what to do!” And I think it takes a while to be chill and not worry about it and realize if someone likes my energy they’ll say so, because they don’t need me to ask them. That’s one of the things Bud is about. He’s all about the erotic possibilities but he has no idea how to tap in. He fails miserably.

For me, the word transformation is rarely applicable outside of situations where there’s some kind of trauma.

Mark: Brooke comes to the playa with a lot of expectations. Her first impression is that these are irresponsible people, they’re just losers who want to party, they just come here to be stylish and sexy and have no depth. So she has this huge expectation of how things should be, wants things to be deeper… and then finds out later. Every single person’s going to have a different take on it, or a different set of needs and wants.

[Alchemical Dependence, and Don’t See Me]

Erik: There’s a real dark side: a profound loneliness, getting separated from people, separated from your own desire, getting confused, getting off; that’s part of the event too, and can have a very transformative effect. For me, the word transformation is rarely applicable outside of situations where there’s some kind of trauma. It seems very rare that people literally transform unless they hit something that’s really difficult.

[Poison Path]

Erik: People say hedonism is a trap, and you end up depleting, or you cause problems in some way. On the other hand the hedonists say no, life should be about pleasure and happiness, and if a pill makes you happy, then take the pill. That “optimistic American” thing is a type of hedonism. There are philosophical hedonists who I respect, a few transhumanists and some others. But I advocate a middle road, which is, if you do embrace the hedonistic ideal, the practice itself will teach you suffering and renunciation. It’s in the thing, unless you’re not paying attention. Some people will say no, you can just keep becoming happier and more fulfilled, and more expansive. But then you’re going to watch everything you know and love go away when you die; so it’s not the whole picture.

That “optimistic American” thing is a type of hedonism.

Once there, the newbies journey along a phantasmagorical picaresque, alternately challenged and rewarded by the various entities they encounter, both on the playa and in themselves. But these spaces, virtual and real, are radically more dangerous and destabilizing than perhaps expected.

[Burning Man Lawyers Sing What’s on the Back of the Ticket, and Darko]

More Persephone than Alice, the newbies are seduced by the sweet seeds of possibility, or even just curiosity (which is all possibilities in potential), and are held in thrall by Hades, for a chthonic, alchemical journey of transformation, perhaps partly or wholly unwanted. But, perhaps, annealing. We have the technologies, we can rebuild you wholesale. Like psychedelics — this trip is a commitment, there’s no way to short-circuit the ride. And the trip is not limited to newbies. It can happen every time, in different ways, via different routes.

Mark: The first hit you get is “road warrior”: you personally are going to have to survive. Then you get to how do we survive the apocalypse. There’s also how do you enjoy the apocalypse? Then what the show really says at the end is, this is your personal apocalypse. Maybe you will be transformed… I don’t know; that’s the unexplainable thing.

Erik: I especially wanted drugs to be there because there aren’t a lot of cultural representations of contemporary drug use that are not super-seamy. But part of the experience on the playa is participation in a cognitive, conceptual experiment, a certain kind of intensification of systems. Whether it’s your nervous system, the cultural system, the system of how lights organize space, there are definitely a lot of chaotic systems out there, and drugs are one way of tapping into that. And then it’s also incredibly sexy in a fun way. If you’re putting on a show, why wouldn’t you include it?

Mark: I got to Burning Man because of psychedelic drugs; the desire to find, not drugs, but people who understood why that was compelling. It has been so underground. And what I found is that it’s all over the place, it’s not just Burning Man.

Whether it’s your nervous system, the cultural system, the system of how lights organize space, there are definitely a lot of chaotic systems out there, and drugs are one way of tapping into that.

Erik: There was definitely some Jesus Christ Superstar going on musically, along with a certain countercultural, spiritual urgency. My experience doing DJ Christ Superstar on the playa in 1999 definitely informed that. And we wanted to have the songs be able to stand on their own, like in Hair. I used to listen to that record all the time when I was a kid, and it wasn’t until I saw the movie that I realized, oh, there’s a story! I had thought it was a bunch of cool songs, that it was a rock record. We didn’t want our songs to be too narrative, for that reason. It was perfect for the playa stories because what it meant was that the newbies could have a series of adventures that were kind of random; they are all interconnected in some weird synchronistic way, maybe — or maybe not.

Jesus Christ Superstar is one of the most perfect pieces of theater ever made; much better as record than as a play. Incredible audio-opera.

Mark: Jesus Christ Superstar was one of the first rock records I ever heard. I grew up in a very small town, very conservative, and by the time I was in 6th grade I had heard Elvis, and what I called 50s music. Do-wop. My dad had really hardcore jazz, like xylophone solos, very esoteric. He stopped buying music in 1955, 1960 or something. And then I had my children’s records, those were huge because children’s records from the 50s and 60s were awesome. But the first rock record I heard — besides Sgt. Pepper’s (we bought a used car and that was in the 8-track, lucky me, huh?) — was Jesus Christ Superstar. My aunt had built a cabin in our woods, like a good hippie, and when she was gone to work I would sneak in and play this one record, Jesus Christ Superstar, over and over and over again. That’s one of the most perfect pieces of theater ever made; much better as record than as a play. Incredible audio-opera. And Erik had a very similar experience with Jesus Christ Superstar. We didn’t actually sit down and analyze it, but we wanted it to have that much guitar work, big, heavy, in-your-face guitar. Also, being from Seattle I have the grunge influence to draw from. And then, classical — I’ve been writing musicals and operas for 20 years and that just pulling from everything I could possibly find.

[Poison Path]

Mark: There’s everything in there from Bulgarian Women’s Choir rip-offs to barbershop quartet — I sit down and I start singing it and it just pops out. For the barbershop quartet song, I did one part at a time, I just improv’d it: I did the tenor, then I improv’d the next one, and the next one, and the last one, and that’s what it is.

How To Survive the Apocalypse supplies the big themes, along with the big visuals. And it supplies the rock. Springing fully-formed from the musically polymorphous mind and voices of composer Nichols, the score and songs catch a carnivalesque that hooks just under the skin, just before your mind starts listening. As it will, as there is much to chew on and listen to. The music is primal and intellectual and rock’n’roll and avant-garde and eminently listenable, all separately and all at once, skipping lightly over the over-marketed middle, like the Sound always does, in any genre.

My previous operas are all about apocalypse. For example, the first one was called Little Boy Goes to Hell, and it was about me, as a 7-year-old, going to Hell, visiting me as a 24-year-old, in Hell.

Mark: My previous operas are all about apocalypse. For example, the first one was called Little Boy Goes to Hell, and it was about me, as a 7-year-old, going to Hell, visiting me as a 24-year-old, in Hell. The second one was Joe Bean, about Job as a rich hippie who loses everything. I’ve been into this theme of either community, or dark catharsis coming through transformation, for a long time.

Erik: People go to festivals to feel good, to feel optimistic, to feel pleasure, to feel transcendence, to feel released, to feel inspired, and those are all very powerful feelings. If there’s going to be someting more that comes out of it other than just a little burst of Mardi Gras, then it’s going to be through that process, not in relationship to it.

Mark: I like the bunny (Bulldada). The bunny’s the best to me because it’s sort of the anti-theater. He chips away at everything. He’s always one step ahead of the audience in terms of, is it going to be dumb, because it’s a musical. It’s good to have this perspective of the loner who’s picking on things. That’s sort of the kernel of the story, that there’s always the opposite around the corner. In the clash scene, Stetson says something that’s great, and then he’s one-upped by the next comment from Mustachio, then he one-ups that, then that gets one-upped, and you just can’t imagine how its going to keep going, because they’re all so right. There are so many perspectives on what Burning Man is about… and the fact is, that it really isn’t about anything.

There are so many perspectives on what Burning Man is about… and the fact is, that it really isn’t about anything.

Erik: There’s a kind of deep, cynical undertow in the themes; Bulldada (my character) gets to be extremely sarcastic, but he’s also a truthteller – there’s something about cynicism and sarcasm which is often much closer to the truth than the things it’s commenting on. But at the same time, there’s the spirituality, that goofiness, that romper room rave vibe which is very much a part of Burning Man as well.

Mark: Burning Man was like a real live version of the stuff that I used to fantasize about.

I can’t tell you any more. Go see the show! If you’re Burn-curious, if you’ve Burned so long you’re crispy, or if you just want to see showstopper musical theater, How To Survive The Apocalypse will deliver. A contact high comes with the ticket. And if the curtain falls, only to tumble the fourth wall, you may be tempted to tarry in the autonomous zone of your ticketed temporary intentional community.

There’s just one thing the show cannot do, that it is not intended to do. That no one can do — except you.

You’ll just have to go.

How to Survive the Apocalypse will play at King King in LA on Sunday, November 20.

How to Survive the Apocalypse CD’s available now from CDBaby.

How to Survive the Apocalypse website.

Erik Davis: Techgnosis

Mark Nichols: The Really Big

Burning Man

Drawings here and in CD booklet by Peggy Nelson; I did the HTStA CD cover design as well. In 1999 I did the set design for DJCS, my first Burn.