Early ’60s Horror (3)

By:

November 16, 2011

[Third in a series of posts by David Smay on horror movies of the early 1960s.]

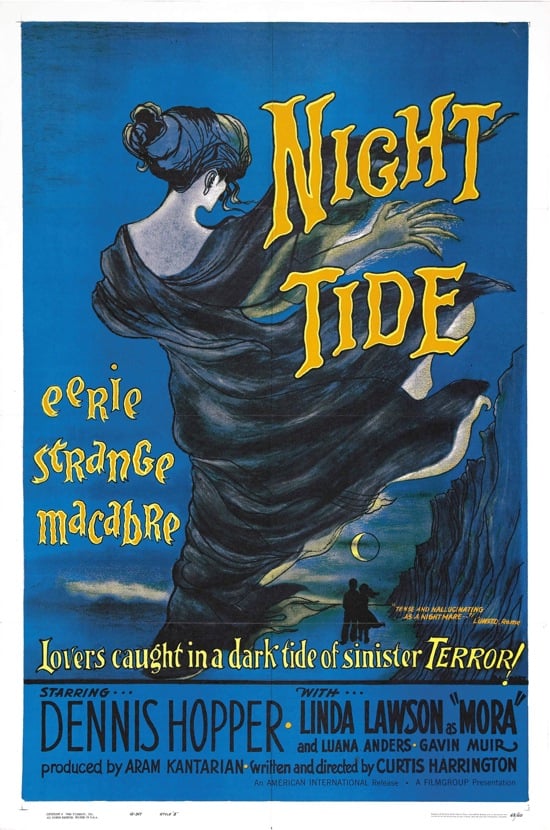

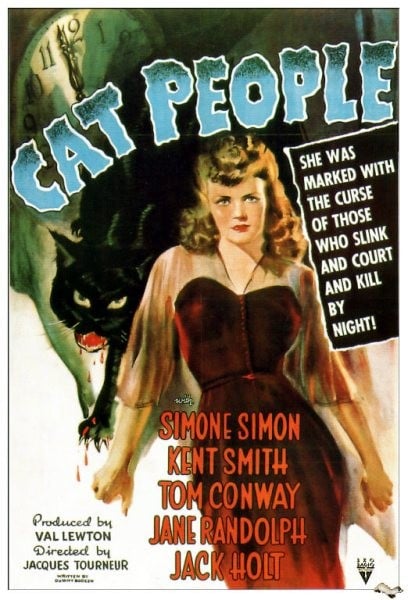

Cat People (1942) is a talismanic movie. Filmmakers, writers, critics, fans touch on it, refer to it, emulate it, steal from it, invoke it. Val Lewton’s disciples Jacques Tourneur and Robert Wise consciously returned to their RKO roots when Tourneur did Curse of the Demon (1957, aka Night of the Demon) and Wise did The Haunting (1961). In the movie The Bad and the Beautiful (1952) Kirk Douglas’ producer character steals a move from Lewton when he rejects the costumes for Doom of the Cat Men and opts to create a horror movie where the monster is implied rather than shown. (And the rejected Cat Men costumes later show up as the basis for the creepy rabbit costume in Donnie Darko.) Night Tide (1961) was the first horror movie to lift the plot from Cat People entirely, but it failed to maintain that balance required by the fantastic we see in Tourneur’s film, and understanding that balance is the key to Liminal Horror.

The classic critical work on fantastic literature is Tzvetan Todorov’s The Fantastic: A Structural Approach. Todorov created a new taxonomy to classify fantasy based upon notions of The Uncanny and The Marvelous, which has proven to be a richer, more flexible approach than earlier psychological (horror as an expression of forbidden desire, or pathology) or sociological interpretations (horror as the nightmare of the culture expressing the fears of each era).

The fantastic, we have seen, lasts only as long as a certain hesitation; a hesitation common to reader and character who must decide whether or not what they perceive derives from ‘reality’ as it exists in the common opinion. At the story’s end, the reader makes a decision even if the character does not; he opts for one solution or the other, and thereby emerges from the fantastic. If he decides that the laws of reality remain intact and permit an explanation of the phenomena described, we say that the work belongs to another category: the uncanny. If, on the contrary, he decides that new laws of nature must be entertained to account for the phenomena, we enter the genre of the marvelous.

Let us take a closer look then at these two neighbors. We find that in each case, a transitory sub-genre appears: between the fantastic and the uncanny on one hand, between the fantastic and the marvelous on the other… . We may represent these sub-divisions with the help of the following diagram:

UNCANNY | FANTASTIC-UNCANNY | FANTASTIC-MARVELOUS | MARVELOUS

…Let us begin with the fantastic-uncanny. In this sub-genre events which seem supernatural throughout the story receive a rational explanation at its end. If these events have long lead the character and the reader alike to believe in an intervention of the supernatural, it is because it is because they have an unaccustomed character. Criticism has described, and often condemned, this type as ‘the supernatural explained.’

[NOTE ON DIAGRAM: The fantastic is represented, in Todorov’s diagram, by the median line separating the fantastic-uncanny from the fantastic-marvelous. Why? Because the nature of the fantastic is, according to Todorov, a frontier between these adjacent realms.]

Night Tide transports Cat People to Los Angeles in the early 1960s, specifically Venice Beach and the Santa Monica Pier, and the exotic woman is purported to come from a race of mer-people, rather than a were-panther of repressed sexuality. Mora (Linda Lawson) plays a Mermaid at a sideshow attraction on the San Monica’s pier run by her adoptive father, Captain Murdoch. Johnny (a young Dennis Hopper) discovers her at a The Blue Grotto, a jazz club. The famous scene in Cat People where Simone Simon’s character is approached by a mysterious woman (played by Elisabeth Russell) who speaks to Simon’s Irena in an unknown language — a scene of recognition and otherness — is replicated exactly in Night Tide with the mystery woman here played by Cameron.

As in Cat People, the normal guy falls for the exotic girl and the film unspools at a languid (tidal even) pace, punctuating their romance with eerie events. Nothing that Curtis Harrington brings to Night Tide compares to the control and pacing that Tourneur exhibits in the famous pool scene in Cat People. Which is understandable as it was Harrington’s first feature film, and first genre film. The movie is beautifully shot (something not apparent until its recent restoration by the Academy Film Archive), and Harrington’s camera glides knowingly through the beach culture, creating a lyrical, dreamlike atmosphere. More crucially Night Tide lacks the core metaphor of Cat People, which derives from Irena’s fear of her own sexuality and its destructive power. In Night Tide, Mora is naturally sensual, capable of determining her own fate until she’s manipulated and destroyed by her duplicitous mentor.

There is some sense of appeasement in the genre narrative, and Harrington’s film works best when he bends away from the story: letting the tarot reading with Madame Rovanovitch (Marjorie Eaton) unfold naturally, Johnny being lead astray (yet not) by the enigmatic Cameron, capturing shadows on a rock in a beach party during a bongo master breakout (by Chaino!), digging deep into a real jazz scene instead of faux beatnikiana, or building a tense, loaded scene in Captain Murdoch’s (Gavin Muir) apartment (creepily appointed with severed hands).

Curtis Harrington came from an experimental film background, an acolyte of Maya Deren and peer of Kenneth Anger. It was while working on Anger’s Inauguration of the Pleasuredome that Harrington came to know Cameron, the Zelig of West Coast esoterica. The invisible presence that draws all these people together, including Dennis Hopper, would be the artist Wallace Berman whose wide circle of friends, collaborators and co-conspirators defined the visual culture of the West Coast Beats. Berman co-founded a film distribution group with Harrington (along with the Eames Brothers), suffered an obscenity trial for showing Cameron’s art and was intimately tied with Dennis Hopper through Bruce Conner. (Curiously, Russ Tamblyn, one of the stars of The Haunting, was also part of Berman’s circle. It was no accident that David Lynch later used Tamblyn and Hopper. As a visual artist and budding filmmaker arriving in Los Angeles in 1971, he certainly would have been aware of Berman and the work of Anger.)

All of these elements give Night Tide a fascination. That deep immersion in Los Angeles beat culture, and that sure sense with the jazz scenes, and the thoughtful borrowings from film history combine with the weird sense of doubling as underground figures act out a primal passion play. At its best it conveys both a documentary capture of Venice and the Santa Monica pier in the early 1960s and some of Anger’s alchemy: film as Magick.

But the ending wakes us rudely from that dream, and it’s worth examining what happens when you jerk a story back to the real. The boundary between uncanny and uncanny-fantastic is a difficult territory to negotiate, and stories which resolve on the side of the uncanny, with “the supernatural explained” leave the reader or viewer feeling cheated, especially if the explanation is mundane. Psycho survives a plot twist reveal at the end which receives an analyst’s explanation because the grotesquery of mummified mommy cross-dressing cadaver still shocks. No matter how much psychoanalysis they blather in voiceover, Hitchcock stays with the tight close-up of Norman Bates’ unnerving smile. Night Tide’s resolution, especially the implication that Johnny’s just going to go trotting off with the nice girl from the Carousel concession, not only destroys the sense of mystery which the movie successfully created but feels sentimental and trite.

Once upon a time, fantastic tales came with a cultural need for plausible deniability. It was a dream, or born of opium or a tale told by a mad man. The marvelous was recanted, we were returned safely to the world we knew. At some point the narrative trope stopped being reassuring and became insulting, a narrative blunder indicating, perhaps, a lack of faith in the audience. Night Tide works like a lyrical trapeze act that faceplants the landing.

While American film looked to Lewton’s work to create a canon of the fantastic, European films came from a different tradition, and bowed to a different master — Jean Cocteau. In my next installment I’ll look at Cocteau’s influence on Franju’s Eyes Without a Face and Roger Vadim’s Blood and Roses.

Screengrabs via Breakfast in the Ruins.

MORE HORROR ON HILOBROW: Early ’60s Horror, a series by David Smay | Phone Horror, a series by Devin McKinney | Philip Stone’s Hat-Trick | Shocking Blocking: Candyman | Shocking Blocking: A Bucket of Blood | Kenneth Anger | Sax Rohmer | August Derleth | Edgar Ulmer | Vincent Price | Max von Sydow | Lon Chaney Sr. | James Whale | Wes Craven | Roman Polanski | Ed Wood | John Carpenter | George A. Romero | David Cronenberg | Roger Corman | Georges Franju | Shirley Jackson | Jacques Tourneur | Ray Bradbury | Edgar Allan Poe | Algernon Blackwood | H.P. Lovecraft | Clark Ashton Smith | Gaston Leroux |

OTHER HILOBROW SERIES: FITTING SHOES — famous literary footwear | POP ARCANA — spelunking weird culture | SHOCKING BLOCKING — cinematic blocking