Our hives, ourselves

By:

November 13, 2011

Why we’ve never been able to resist finding human-sized meaning in bee-sized hives.

[This article first appeared in The Boston Globe’s IDEAS section, on June 19, 2005.]

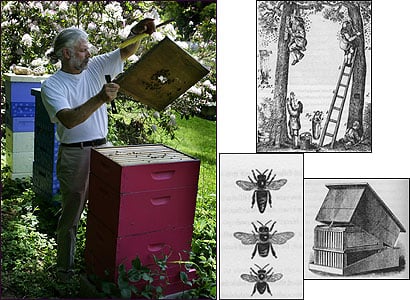

It’s an unusually warm day in mid-May, and Ken Leavitt is using his hive tool, a crowbar-cum-scraper suited for burglary or home renovation, to pry the lid off of one of his “deeps,” a capacious wooden box hung with 10 wood-and-beeswax frames seething with thousands of honey bees. The bees, along with the others in his five purple-and-white hives perched on a hillside overlooking the greenhouses of Allandale Farm on the Jamaica Plain-Brookline border, the last working farm in the area, are, as they say, busy.

A voluptuous odor, somewhere between a bakery and a brewery, rises to our nostrils. Leavitt plucks out one of the brood frames barehanded and scans the comb closely. To Leavitt, the frame he’s scrutinizing is both an X-ray and an interactive aerial map of a miniature civilization. He’s searching not only for evidence of diseases and pests like foulbrood and mites but for social disorder: sprawl, a dysfunctional ruler, overpopulation, demoralized workers.

“Nice pattern,” Leavitt says quietly, as much to the bees as to me. Worker bees move purposefully about, secreting and kneading wax to make more comb, readying brood cells for the queen’s eggs, tending to the hive’s young, and receiving nectar from forager bees before laboriously processing it into thick, spring-sweet honey. For every communal pound of honey they’ll produce over the course of the season, Leavitt’s bees will tirelessly crisscross more than 8,000 acres, pollinating flowers and kitchen gardens in Jamaica Plain, Brookline, Roslindale, West Roxbury, and Newton along the way.

This arrangement suits Leavitt, a tall, muscular man of 57 whose ponytail and beaded necklace mark him as a pregentrification denizen of Jamaica Plain. Long before he started keeping bees, he says, he believed in the honey bee’s ethos of “working hard and feeding the community,” as he puts it. In the 1970s and ’80s, he helped open and run restaurants that became Five Seasons (a pioneering vegetarian eatery on Centre Street), Blackbird Kitchen, and Centre Street Cafe. “I liked making cheap, nourishing food for my friends and neighbors,” Leavitt says.

It’s impossible, it seems, not to look into the hive and see a more diligent, community-minded, and orderly version of our own society. From the “Georgics” of Virgil, which praised honey bees because “they alone hold children in common: own the roofs/of their city as one: and pass their life under the might of the law” to the 1609 English beekeeping treatise The Feminine Monarchie to female-centric idylls like Zora Neale Hurston’s Their Eyes Were Watching God and Sue Monk Kidd’s 2002 bestseller The Secret Life of Bees, writers have sung the praises of these insects. And beekeeping itself has given us lasting metaphors: To eke out a living, for example, is to add another eke, or extra straw coil to a skep, as a domed straw beehive was known in medieval England.

Indeed, as a recent bumper crop of new books about honey bees makes clear, despite centuries of demystification of hive life by scientists, we may never tire of finding human-sized meaning inside bee-sized hives.

Though he scoffs at bygone notions about the virgin birth of bees, among numerous other misapprehensions, Stephen Buchmann is by no means immune to the unscientific tendency to see in bees “meaningful symbols representing some of our most profoundly held beliefs,” as he puts it. Buzzing briskly across the history of civilization, Buchmann’s Letters from the Hive (Bantam) demonstrates how prominently bees (as emissaries and incarnations of gods) and honey (as nectar, ambrosia, and fermented mead) figured in the myths and rituals of ancient Egypt, India, and Greece.

A globe-trotting entomologist known for his work on the problem of the world’s disappearing pollinators, Buchmann admits that his compendium of honey-hunting tales, racy descriptions of bees’ visits to “perfumed courtesans” (flowers), and honey-based recipes is designed to make the public sympathetic to the plight of bees. But that doesn’t quite explain the open letter he appends to the book: Praising bees for their “sense of community service and devotion to the greater good,” not to mention their “cozy, well-organized nests and attack-only-when-attacked policy,” he urges his fellow human beings to emulate them.

Not every observer, however, has looked inside the hive and seen only sweetness and light (as Jonathan Swift described honey and wax). In Bees in America (Kentucky), historian Tammy Horn recounts how British colonists brought with them not only the continent’s first honey bees but pernicious Old World theories about the hive’s perfect efficiency and social stability. Leaders in Jamestown and the Massachusetts Bay Colony, for example, were predisposed to label fellow colonists who didn’t work hard enough as lazy drones deserving to be forced out of society. (On a more upbeat note, we learn that colonists dubbed any social gathering that combined work and pleasure a bee, while the Mormons, who regarded the beehive as an icon of productivity and mutual protection, named their Utah territory after founder Joseph Smith’s word for bee: Deseret.)

But Horn, like Buchmann, can’t resist ending with a call for us to be more like the bees — sort of. “If America is to continue to be a model hive,” she opines in an epilogue referring to her description of the progressive workplaces of 19th-century American bee supply entrepreneurs Charles Dadant and A.I. Root, “we have to take better care of our workers in the new millennium by offering better insurance, better retirement, flexible schedules, and job security.” America needs to become less hive-like, that is, and cease treating its workers like drones in winter.

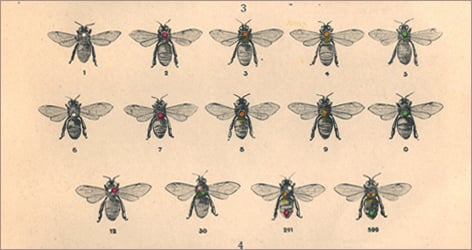

British food writer Hattie Ellis and American journalist Holley Bishop, for their part, are less interested in the meaning of bees than in the history of bee scholarship and the current struggles of independent beekeepers to make a living. Ellis’s Sweetness and Light (Harmony) and Bishop’s Robbing the Bees (Free Press) flit from Aristotle’s semiscientific studies of hives to the more exacting research of blind Swiss scientist Francois Huber, who discovered in the late 18th century how drones fertilize the queen bee, and Austrian zoologist Karl von Frisch, author of the Cold War-era decryption of the honey bees’ dance. We also meet Lorenzo Langstroth, a troubled former minister from Andover, who in 1851 revolutionized hive design, producing the model still used today.

Still, in their efforts to convince us to eschew bland supermarket honey from China, Canada, or Mexico in favor of local brews, both Ellis and Bishop can’t resist taking off on flights of metaphor and simile. “A colony of bees is like a sponge, soaking up the pools of smell and taste from the flavorful landscape and season in which it is immersed,” writes Bishop, in one of her many lyrical descriptions of local honey. For her part, Ellis describes the honey-making process as a form of alchemy: Honey, she writes, is “a sweet, fragrant river from a million tributaries, carried across the air and flowing gold into the pot through the transforming power of the bee.”

I was tempted, upon reading these books, to dismiss as dated the inclination to hold up bees as models for the way we should live. After all, ours is a chastened era that regards the very idea of a perfectly ordered society as totalitarian and celebrates instead the idea of more freewheeling, self-ordering networks.

But then I remembered that even network-culture enthusiasts take inspiration from bees. In his 1994 book Out of Control, Kevin Kelly, a founding editor of Wired magazine, argued that everything from the Internet to markets to democracies were “swarm systems,” hive-like collections of thousands of autonomous members that are highly connected to each other, but not to a central hub. More recently, in Emergence (2001), technology writer Steven Johnson used the collective intelligence of social insects like bees as a metaphor for such complex systems as brains, software, and cities.

Steven Johnson, meet Virgil. Although these technofuturists’ enthusiasm for peer networks, persistent disequilibrium, and Amazon.com’s “Customers who bought this book also bought…” feature is infectious, the goal of learning from honey bees the secret of “control without authority,” as Kelly writes at one point, strikes me as undesirable. People who actually spend their working days with bees, it seems to me, come away with far less exalted visions of what it might mean to live a good life.

Five years ago, Leavitt (who also owns and operates a massage therapy business), purchased the hives at Allandale Farm from a beekeeper acquaintance who had been stung so badly she nearly died. Though he often works without a veil or gloves, he remains acutely aware that bees are untamed; a beekeeper doesn’t control bees, he tells me, but merely diverts their natural tendencies to new ends.

Last weekend, I visited Allandale Farm again, to give Leavitt a hand as he started a sixth hive, using a brood chamber borrowed from one colony and a mite-resistant queen he had ordered by mail. Earlier this month, he had placed shallow “supers” of empty honeycomb atop his hives, taking advantage of the fact that bees are instinctive hoarders who will store up far more supplies than they need. In the fall, he’ll harvest 600 pounds of Boston-brewed honey, some of which he’ll sell locally, and the rest of which, naturally, he’ll share with his friends and neighbors. He wordlessly pressed on me a heavy, unlabeled jar of his honey, so fragrant and potent that I handled it with extreme care, as though it might detonate.

As I crouched by the hives in the hot sun that morning, a cloud of discombobulated bees winging around my head and nectar dripping down my forearms from the brood frame I was gripping with the anxiety of a nonbeekeeper, I recalled Sylvia Plath’s grim lines about the buzzing of bees:

It is the noise that appalls me most of all,

The unintelligible syllables.

It is like a Roman mob,

Small, taken one by one, but my god,

together!

Try as I might at that moment, I could call no comforting metaphors to mind.

READ MORE essays by Joshua Glenn, originally published in: THE BAFFLER | BOSTON GLOBE IDEAS | BRAINIAC | CABINET | FEED | HERMENAUT | HILOBROW | HILOBROW: GENERATIONS | HILOBROW: RADIUM AGE SCIENCE FICTION | HILOBROW: SHOCKING BLOCKING | THE IDLER | IO9 | N+1 | NEW YORK TIMES BOOK REVIEW | SEMIONAUT | SLATE

Joshua Glenn’s books include UNBORED: THE ESSENTIAL FIELD GUIDE TO SERIOUS FUN (with Elizabeth Foy Larsen); and SIGNIFICANT OBJECTS: 100 EXTRAORDINARY STORIES ABOUT ORDINARY THINGS (with Rob Walker).