Early ’60s Horror (2)

By:

November 8, 2011

[Second in a series of posts by David Smay on horror movies of the early 1960s.]

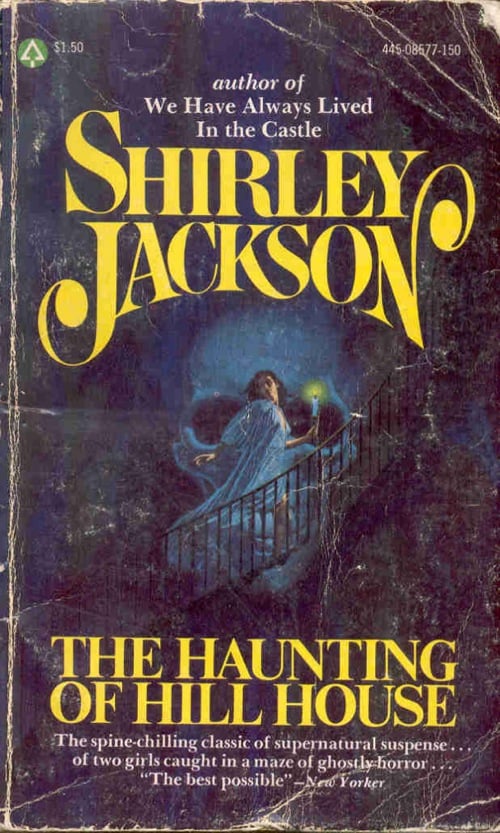

Critics tend to pair The Haunting (dir. Robert Wise, 1963) with The Innocents (dir., Jack Clayton 1961) as classics of psychological horror. Kimberly Lindbergs, in her blog Cinebeats, rightly links the two movies in a lineage of horror movies starting with Cat People (1942) and continuing through Roman Polanski’s Repulsion (1965) where the horror seems to manifest directly from a woman’s repressed sexuality. They’re seen as masterpieces of suggestion and ambiguity featuring A-List actors in handsomely mounted literary adaptations by well-established and regarded directors. Likewise, Carnival of Souls (dir. Herk Harvey, 1962) and Night Tide (dir. Curtis Harrington, 1961) come as a matched set as they’re both low-budget, feature carnivalesque settings, and were made by first-time directors producing haunting images that float free of the plot.

I’m gong to shuffle the deck, though, and consider The Haunting alongside Night Tide, because they’re the two most obvious heirs to Val Lewton’s aesthetic. Lewton’s story has become well known in part because of Martin Scorsese’s documentary about him, which frequently airs — along with Lewton’s movies — on TCM. In brief, Val Lewton was a “Story Man” who came up with David O. Selznick, and when RKO Pictures all but bankrupted itself on Orson Welles’ The Magnificent Ambersons, it was Lewton’s low-budget movie Cat People that salvaged the studio. Thereafter, some suit would assign him a screaming exploitation title like I Walked With a Zombie, and Lewton would set Jane Eyre in Haiti, then scour the lot and figure out yet another use for the grand staircase from Ambersons.

Lewton’s RKO movies famously differed from Universal’s stable of horror icons (Dracula, Frankenstein, The Mummy) because he never showed his monsters, letting them linger in the shadows and the imagination. This style has come to be championed over time as a preferable (more tasteful, more middlebrow) style than the gory horrors that followed. There’s a weird element of revisionism that’s been traveling with this sentiment, dragging James Whale alongside Val Lewton. While Whale’s films were certainly stylish and elegant, the original Frankenstein monster’s makeup in Universal’s 1931 film was considered shocking in the extreme, and notable for leaving nothing to the imagination, the very face of horror.

Even stranger, Psycho is now held up as an anti-gore model of restraint, simply because it was shot in black and white, and you never see the knife hitting Marion Crane. This is pure bullshit; Psycho was seen in its time as close to pornographic in its violence. It was scandalous, and the fact that the shock of the shower scene derives from its editing and score doesn’t make it any less violent. The editing and score don’t eschew cinematic violence, they redefine it.

While The Haunting retains its status as one of the great exemplars of the Lewton style, there’s been a contrarian shift in critical thinking among horror critics about how Robert Wise achieves his effects. Unlike Lewton, Wise doesn’t leave everything up to artful shadows and insinuation.

I have to laugh when people use words like “subtle” and “suggestive” when describing The Haunting. Make no mistake, this is an aggressive mind-fuck campaign you’re witnessing. — Unkle Lancifer, Kindertrauma

It may sound ridiculous, but The Haunting is, in its way, every bit as explicit as a Herschell Gordon Lewis movie…critics have mistaken a lack of gore and special effects for a lack of aggressive shock tactics — they’ve simply failed to notice those tactics because the movie targets the ears rather than the eyes. — 1000 Misspent Hours

In short, Wise’s cinematic shocks were critically invisible simply because they’re not dripping with red blood. Whereas Hitchcock achieves his effects in Psycho with editing and the musical score, Wise generates jolts and tension with sound effects and art direction. It’s true that Wise never shows us a monster, but it’s no less disquieting to see scowling faces implied in the woodwork, and the scariest scene features brutally loud sound effects.

Robert Wise received his first directing job (on the sequel Curse of the Cat People) under Val Lewton and worked in Lewton’s RKO unit before that as an editor. After an enormously successful career, Wise returned to his horror roots in the early 1960s specifically to apply the lessons he learned from Lewton, and the director Jacques Tourneur, to a new film. There’s an interesting series of overlays in The Haunting in that Wise consciously emulated Lewton, but also that Shirley Jackson’s novel The Haunting of Hill House is in many ways a response to “The Turn of the Screw.” The movie makes this connection explicit with the brief set-up scenes involving the wicked attendant to Hill House’s heir and the lusty sex she has with a farmhand, linking that corruptive sex to the evil in the house, echoing Peter Quint and Miss Jessell in “Turn of the Screw.” Similarly Nell in The Haunting is portrayed as sexually repressed, neurotic and needy in a way that parallels that of the governess in “Turn of the Screw.”

Nell’s story begins not unlike that of Marion Crane’s in Psycho; they are both women who are taking a huge gamble to change their lives, leaving everything behind and driving towards not just a destination but a redefinition. Nell’s tragedy is that she’s thwarted on the cusp of this becoming. Again and again in this cycle of early 1960s movies we see women desperate to become somebody new — and being denied. Their faces are not their own. They lose their souls, their lives, their personhood. Yet this cycle of movies is also notable in that female characters have agency, that they are allowed to be protagonists and villains, not simply victims. They all pass the Bechdel test.

Unlike “Turn of the Screw” the evil in Hill House is not primarily Wicked Sex, but Nell’s sexuality is a huge part of the story, particularly in the movie where her relationship with Theo is more provocative and pointed. The more you watch The Haunting the more fascinating and complex their dynamic becomes: needy, supportive, hateful, intimate, loving, rejecting. The point is not simply that Nell is lesbian — she may well be asexual, or just as interested in Dr. Markway. The bigger, darker, more horrifying consummation is Hill House’s desire to claim Nell.

Julie Harris’ performance as Nell is iconic — prickly, anxious, willful — and perfectly matched by Claire Bloom’s bohemian cool as Theo. They’re coded so clearly as lovers they could have stepped right off the cover of a lesbian pulp novel of the era with dark haired, experienced, predatory (in leopard print) Theo pitted visually against the fair-haired, virginal, girlish Nell. Nell’s long hair reads as girlish when it’s down, spinsterish when it’s up. In either case, her character is desexualized so Theo’s intimacies with her are especially provocative, and there is the implication that much of the poltergeist phenomena in the house could be generated by latent telekinesis in Nell. Though this element is foregrounded more in the book, and the movie seems more interested in establishing the malign force of Hill House than having it emanate from Nell herself.

Though the movie tries to get into Nell’s head by way of a voiceover, it functions better by externalizing Nell’s emotional turbulence. In an odd way by deemphasizing the “is she crazy or are there ghosts” plot element, The Haunting simply transfers that tension into a rich, fluid metaphor that gathers emotional power through the course of the movie. While Wise uses every tool in his filmmaker’s kit to deliver suspense, the effect is very different from the impact of a body horror movie which forces you to turn your face away in shock, revulsion, aversion. Slasher and gore movies send you down a narrative rollercoaster of dread and release, emphasizing the physicality of response, explosive as laughter.

I’ve tried to chart the long-standing critical attempts to define the distinction between works of body horror and psychological terror, explicit gore and implicit madness, what Italo Calvino calls the Visionary Fantastic versus the Quotidian Fantastic, what Poe was implying with his “Stories of the Grotesque and Arabesque.” While body horror/gore/grotesque is clear enough, I find “psychological horror” to be misleading, and propose instead Liminal Horror. These movies generate their power in the space where it’s not clear whether the story elements are subjective and interior or actual, but also poised between the supernatural and the everyday.

Body horror generates a very different experience than the sensation cultivated in this early 1960s cycle of Liminal Horror movies, which is a sense of apprehension, an almost delighted bubble of suspense. But what is being suspended is not the next step of the plot, but disbelief. Sir Walter Scott advocates for the narrative cock-tease:

The marvelous, more than any other attribute of fictitious narrative loses its effect by being brought much into view. The imagination of the reader is to be excited if possible, without being gratified. If once, like Macbeth, we “sup full with horrors,” our taste for the banquet is ended and the thrill of terror with which we hear or read of a night-shriek, becomes lost in that sated indifference with which the tyrant came at length to listen to the most deep catastrophes that could affect his house. — Sir Walter Scott, “On the Supernatural in Fictitious Composition.”

There’s a long critical tradition in reviewing Liminal Horror that amounts to a kind of triumphal plot parsing. It culminates in a flow chart that declares definitively (A) “It was all in her head!” or (b) “It was supernatural!” You’ll see the nerd-light shine in their eyes while they explain the significance of Jack being let out of the cold storage locker in The Shining or, if you’re Edmund Wilson, tying you into a knot affirming that in “The Turn of the Screw” the governess imagined it, then recanting that for a supernatural explanation then recanting his recantation.

This is not just tiresome, but distracts from the very virtue of Liminal Horror.

[The fantastic tale’s] theme is the relationship between the reality of the world we live in and know through perception and the reality of the world of thought that lives within us and directs us. The problem with the reality of what we see — extraordinary things that are perhaps hallucinations projected by our minds, or common things that perhaps hide a second, disturbing nature, mysterious and terrible, beneath the most banal appearances — is the essence of fantastic literature, whose best effects reside in an oscillation between irreconcilable levels of reality. — Italo Calvino, p. vii, Fantastic Tales: Visionary and Everyday.

That the narrative in Night Tide loses this balance between the real and unreal makes it a perfect specimen for examining how Liminal Horror works. The Scooby Doo ending thuds too heavily on the side of realism, and a sappy, exposition-heavy, implausible denouement robs the movie of much of its effect. While the narrative of Night Tide fails, the movie does not. But I’ll address that in this series’ next installment.

NB: All screengrabs from Kindertrauma

MORE HORROR ON HILOBROW: Early ’60s Horror, a series by David Smay | Phone Horror, a series by Devin McKinney | Philip Stone’s Hat-Trick | Shocking Blocking: Candyman | Shocking Blocking: A Bucket of Blood | Kenneth Anger | Sax Rohmer | August Derleth | Edgar Ulmer | Vincent Price | Max von Sydow | Lon Chaney Sr. | James Whale | Wes Craven | Roman Polanski | Ed Wood | John Carpenter | George A. Romero | David Cronenberg | Roger Corman | Georges Franju | Shirley Jackson | Jacques Tourneur | Ray Bradbury | Edgar Allan Poe | Algernon Blackwood | H.P. Lovecraft | Clark Ashton Smith | Gaston Leroux |

OTHER HILOBROW SERIES: FITTING SHOES — famous literary footwear | POP ARCANA — spelunking weird culture | SHOCKING BLOCKING — cinematic blocking