Spoiler Alert: Grizzly Man

By:

November 3, 2011

Caveat lector: may contain spoilers.

Grizzly Man, dir. Werner Herzog, 2005.

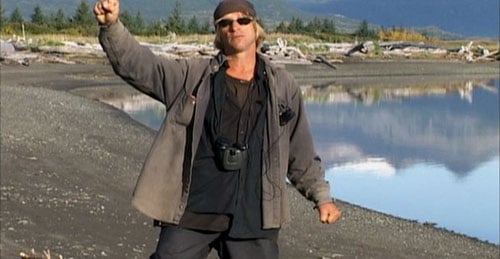

Grizzly Man is two documentaries in one: the first is video shot by Timothy Treadwell, the self-described bear-whisperer, of himself in the Alaskan wilderness; the second is edited and narrated by director Werner Herzog, about Treadwell’s controversial life and death. Herzog weaves these two voices together, the naive enthusiast and the experienced adventurer, while the conflict between man and nature plays itself out to its tragic end.

Before falling in with the bears, Treadwell’s life proceeded in fits and starts. Prone to fantasy and self-invention, at college he claimed to be an orphan from Australia, instead of the average kid from Long Island he actually was. He changed his name from Dexter to the more mellifluous and symbolic Treadwell. He blamed his heroin addiction on losing the part of the bartender on Cheers to Woody Harrelson. After stumbling through various addictions and dreams of glamour, a sympathetic friend recommended that Treadwell go up to Katmai National Park and Preserve in Alaska and take in some nature. At that, Treadwell’s star was set. He successfully swapped his substance addiction for an equally powerful image addiction — the romantic sweep of wilderness, nature, and of course, bears. He would become the man who could talk to the animals.

Treadwell never stopped to consider whether the animals could really talk to him.

Werner Herzog is uniquely positioned to tell this tale. Throughout his prolific career Herzog has been fascinated with extremes — of man, of nature, of the lengths to which we will go to find meaning, substance, wonder, or the fabled far edges of the earth. By mapping the negative spaces of extremity, Herzog has shown us in ever-sharper outline what it means to be human, what it means to be wild, and what it might mean to be free. And as well he has an eye for the absurd, for in the seeming contradictions of our behavior and beliefs often lies the key, not to what we make of it all, but what we all might make of each other.

What Herzog makes of Treadwell is a remarkably sensitive and balanced portrait of a sincere man in a sincerely troubled quest. Making full use of Treadwell’s own footage, Herzog allows the contradictions in Treadwell’s words, friends, and actions to fight it out amongst themselves, all the way to the tragic conclusion.

It is fair to say that Werner Herzog maintains the opposite view of nature from someone like Timothy Treadwell. “The trees here are in misery, and the birds are in misery. I don’t think they — they sing. They just screech in pain.” (Herzog quoted in Burden of Dreams, Les Blank’s 1982 documentary of the making of Fitzcarraldo).

Herzog is no stranger to work in the field, either the natural one or the field of dreams. But where Treadwell’s glasses are permanently rose-colored, Herzog’s lens is perfectly clear, and never shies away from uncomfortable observations; in fact, he revels in them. And as the director of such idiosyncratic Klaus Kinski and Bruno S, Herzog is also familiar with the beautiful yet painful paradoxes of human passion and imagination.

Onscreen, Treadwell seems eager to be a one-man Wild Kingdom episode, playing Marlin, Jim, the cinematographer, and the animals, all rolled into one, with undisguised glee. His unquestioned belief in the romance of landscape, in a view of a wilderness in which we can gain perspective and get in touch with our own real nature, if only we will embrace the idea, is one that has wide appeal, and, to a less extreme degree, wide acceptance.

We miss the wild. There are few really untouched places left anymore; it seems all of nature is managed and bounded and provided with a few roads and signposts to guide our wanderings, as well as helpful naturalists to guide our imaginings. Interestingly, Katmai is just such a managed space, host not only to bear populations but to annual migrations of thousands of tourists and photographers. How Treadwell interacted with these signposts and guides is telling —he pretended they were not there; he insisted, to himself, that he was alone, in the wild, with only his video camera and his wits to guide him.

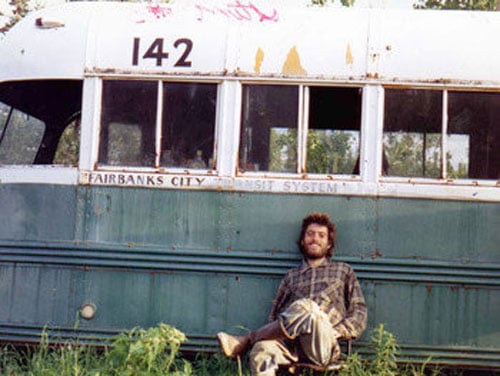

One might be reminded of Chris McCandless, the subject of Jon Krakauer’s book Into The Wild (and Sean Penn’s biopic of the same name), who insisted on walking into the Alaskan wilderness without a map, because he so desperately needed to believe that there was still an unmapped place to call wild. In fact he was only a few miles from a Park Service cabin and a river-crossing tram, and the bus in which he took refuge was specifically placed for hunters, all of which he would have known (and might perhaps have saved his life) had he taken a map and talked to a few more locals. McCandless believed that by discarding the map, both he and the landscape could be free.

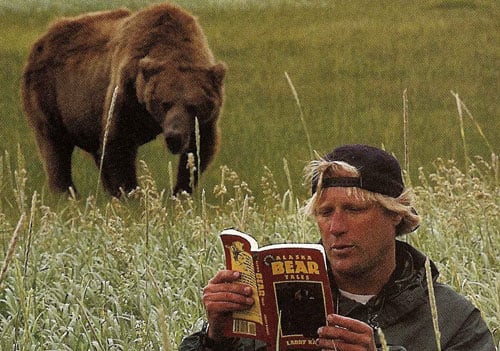

Treadwell took a similar approach. Instead of studying biology and ecology and researching his chosen mammals, Treadwell “threw away the map” in the belief that his approach was more “natural.” But nature is not just what we wish it to be. Superficially, Treadwell might have seemed to be mimicking the methods of immersive research scientists like Jane Goodall and Dian Fossey. But Goodall and Fossey never traded their careful observations for what they wished to be the case. They immersed themselves as zoologists and primatologists, and studied the social primates, who are more tolerant of another primate in their midst with a notebook. As for Treadwell’s claim of bear-whispering; significantly, horse- and dog-whisperers work with domesticated animals. These crucial differences did not register with Treadwell. He petted the bears. He named them: “Cupcake,” “Freckles,” “Taffy.” He set up his nylon tent in the dense brush where they preferred to hide out. He did this all on the strength of his belief that he could be their friend, in much the same way he tried to charm his way through human society.

For a dozen years, his timing was right. The bears had plenty to eat and were acclimated enough to humans in the Park that they tolerated this capering, camping creature who constantly got too close. From the footage, it does not appear that any of the animals Treadwell encountered did more than tolerate him, although he clearly believes he has tamed them like large dogs, or perhaps has even insinuated himself into their society. Back among people, Treadwell made high-profile appearances on Letterman, Rosie and the Discovery Channel.

But eventually, his luck ran out. Given Treadwell’s unshakeable belief in his own beliefs, this was perhaps inevitable. Beliefs tend to run up against the hard wall of reality, only to get knocked flat on their backs. Hit hard enough, that wall will crush not only the beliefs, but the believer.

A version of this essay appeared on the Brattle Theater Film Blog, July 2010.

Read more Spoiler Alerts.

A selection of HiLobrow essays on Werner Herzog:

3D Graffiti: anamorphosis in prehistoric art.

Reality TV: Now in 3D!: Plato, Fred Astaire, and filmmaking.

Hilo Hero: Werner Herzog: on the occasion of The Master’s™ birthday.

Merit Badge #4: Feral Tendencies: Express your other self.

Byss and Abyss: Werner Herzog narrates the life out of a plastic bag.

Wide World of Xtreme Sports: Herzog versus Ernest Shackleton in the Men’s Division.

Anti-Anti Utopians: 1934-43: Joshua Glenn’s Periodization Scheme.