Early ’60s Horror (1)

By:

October 31, 2011

Of all the high-lowbrow movements to streak across the back half of the twentieth century — the French New Wave, Brazilian Tropicalia, Underground Comics, Punk — it’s the early 1960s revolution in horror which is least recognized, least known and least understood. Even the savviest critics of the era missed this tidal change because the very breadth of it rolled in behind larger cultural and generational waves, and what critical focus it drew came wrapped in moral panic and disapproval.

[First in a series of posts by David Smay on horror movies of the early 1960s.]

In 1960 alone, Psycho, Peeping Tom, Black Sunday, and Eyes Without a Face played in theaters. Yet that clutch of five-star masterpieces only represents a fraction of that year’s important work which also saw the Japanese vision of hell, Jigoku, two Hammer horrors in The Brides of Dracula and Two Faces of Dr. Jeckyll, Roger Corman’s first gothic, The Fall of the House of Usher as well as his cult cheapie Little Shop of Horrors, Roger Vadim’s Blood and Roses, and Village of the Damned.

There was really no way to see this happening as it occurred. Psycho dominated both the box office and the mainstream press, and the avid and active horror fandom of the time was too busy looking backward in a happy wallowing glut of old horror movies on television. Even as late as the ’80s with Stephen King’s Danse Macabre and the ’90s with David Skaal’s The Horror Show that early 1960s era was seen as a period of horror quatschification, the uncanny cozily commodified by “Monster Mash” and Famous Monsters of Filmland, horror hosts like Ghoulardi and model kits of The Mummy.

The years between 1960 and 1963 not only saw an unprecedented explosion of masterful film horror, but it was also the golden age of the television horror anthology with great work airing on The Twilight Zone, Outer Limits, Alfred Hitchcock Presents, One Step Beyond and the Boris Karloff-hosted Thriller. Even Roald Dahl hosted his own series for one season in 1961, Way Out. If you think of Psycho as the Never Mind the Bollocks of the era, with Black Sunday as The Ramones’ Leave Home, you can see the shorter, sharper shocks of TV horror as the ceaseless spew of fantastic punks singles by Stiff Little Fingers and The Ruts and The Only Ones. (By this analogy, The Twilight Zone stands as the great singles band of the era. In short, it’s the Buzzcocks’ Singles Going Steady.)

Another complicating factor in the invisible ubiquity of early ’60s horror were the censors’ scissors which snipped away the most potent scenes in Eyes Without a Face and Black Sunday which toured in butchered versions. (Eyes Without a Face infamously played across the south as The Horror Chamber of Dr. Faustus coupled on a double-bill with The Manster.) It was only in the early twenty-first century when Criterion released definitive DVD releases of Eyes Without a Face, Jigoku (long rumored and rarely seen in the West), Carnival of Souls and Peeping Tom and Mario Bava’s work came out in uncut, remastered editions that the impact of the work came into focus.

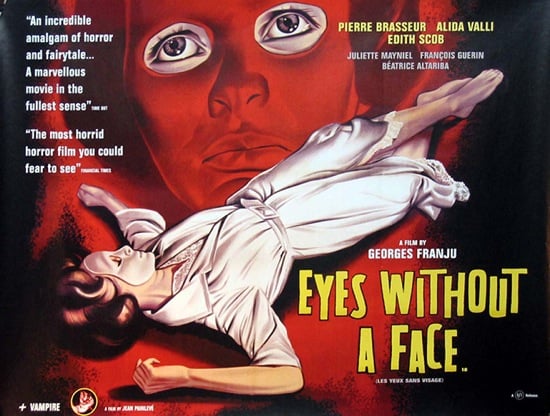

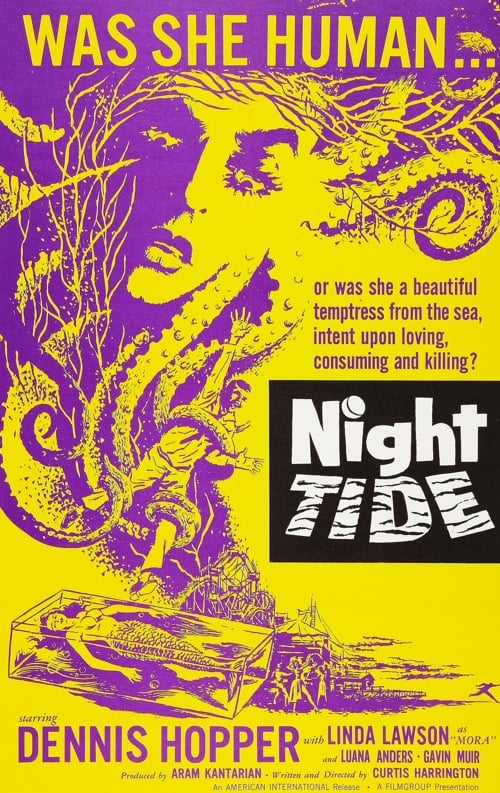

And still, it’s difficult to wrap your brain around the era because not only did it produce an arterial spray of great films, and iconic television episodes, but it came in such an unwieldy, critically resistant mass. Black Sunday and The Fall of the House of Usher both consciously copied the success of Hammer’s gothics, but one launched the Italian horror industry, while the other set off the most important horror cycle in American independent film. Psycho and Peeping Tom both circled around mentally bent protagonists in mundane, contemporary settings, but Hitchcock had his greatest success, while Powell’s career was destroyed. No single critical theory encompasses the high literary adaptation of The Innocents (based on James’ Turn of the Screw), Psycho killers, the Poe/Stoker/Shelley gothics, the era-capping gore of Blood Feast, the camp satire of Whatever Happened to Baby Jane, the Cocteau-derived Eyes or the dreamy Val Lewton influence on The Haunting and Night Tide.

The critical language itself fumbles trying to parse these distinctions. In Danse Macabre Stephen King articulates a difference between “horror” and “terror” which parallels a long-standing divide between “body horror” and “psychological horror.” But even “psychological horror” is a baggy term that conflates Crazy Killers (i.e., Psycho and its many imitators) with narratives wavering on the edge of the supernatural (i.e., “The Turn of the Screw” and its many imitators). The longstanding middlebrow bias against body horror, violence and gore fueled outright censorship and also a kind of tut-tutting disdain. Both Georges Franju and Michael Powell suffered critical hits for lowering their distinguished careers into the horror gutter, a move seen as both unseemly and crassly money-grubbing.

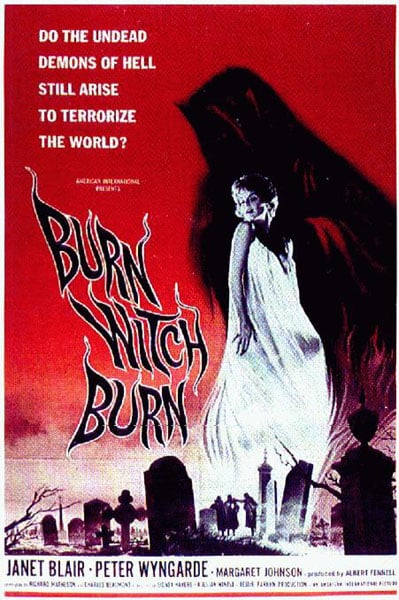

Within just this four-year span from 1960 to 1963, horror covers a vast landscape, so in my next section I’ll carve a narrower path, looking at the films The Haunting, The Innocents, Blood and Roses, Night Tide, Eyes Without a Face, Carnival of Souls and Burn, Witch, Burn. These movies are linked by an emphasis on uncanny dreaminess over body horror (not that there’s anything wrong with that!), and women who aren’t running from chainsaws, but walking slowly towards their fearful desires.

I’ll explore the porous boundaries between the art film and horror in this era, recruit Italo Calvino to explain the difference between “the fantastic” and “the marvelous,” and make compelling yet insupportable claims for the unethical virtues of horror.

MORE HORROR ON HILOBROW: Early ’60s Horror, a series by David Smay | Phone Horror, a series by Devin McKinney | Philip Stone’s Hat-Trick | Shocking Blocking: Candyman | Shocking Blocking: A Bucket of Blood | Kenneth Anger | Sax Rohmer | August Derleth | Edgar Ulmer | Vincent Price | Max von Sydow | Lon Chaney Sr. | James Whale | Wes Craven | Roman Polanski | Ed Wood | John Carpenter | George A. Romero | David Cronenberg | Roger Corman | Georges Franju | Shirley Jackson | Jacques Tourneur | Ray Bradbury | Edgar Allan Poe | Algernon Blackwood | H.P. Lovecraft | Clark Ashton Smith | Gaston Leroux |

OTHER HILOBROW SERIES: FITTING SHOES — famous literary footwear | POP ARCANA — spelunking weird culture | SHOCKING BLOCKING — cinematic blocking