Do Not Screen

By:

October 11, 2011

A late night; tired, disoriented travelers; an abandoned barn. A nondescript box amidst the rubble and rusted farm implements. In the box: tantalizing fragments, oddly snipped into 12-frame lengths. Further: some in envelopes, snipped like the others, but labelled “do not screen.” A filmmaker painstakingly collects and assembles the fragments, slowly revealing…

It may be a plot for a movie, a conspiracy thriller referencing ancient secrets, a government cover-up, hidden Nazis, a wrinkle in time. And in fact, it is a plot, although not in that way. Not yet, that is.

One late night, writer Nicholas Rombes pulled over to stretch his legs on a long drive. Wandering a bit from the road and peeking into a long-abandoned barn, he discovered a nondescript box. Which contained oddly-snipped 12-frame fragments, some in mysterious envelopes, labeled “do not screen.” Intrigued, he hurried home with his find, to painstakingly collect and assemble…

Here is where the real script diverges. Instead of beginning the reconstruction process himself, The Mystery of the Lone Re-arranger, Rombes has instead partnered with The Critical Media Lab at Ontario’s University of Waterloo to scatter it to the winds, mailing the real fragments to interested participants, along with an embedded code, and programming a virtual timeline, irregularly populated as the codes are called in. A wise move — should there emerge evidence of a latent conspiracy, the silencers cannot target the lone fanatic in his evidential basement. Instead the reconstruction involves a growing web, as everyone who agrees to participate becomes complicit upon receipt.

Rombes has an unusual take on film. With previous and ongoing projects such as 10/40/70, and The Blue Velvet Project, he offers a close reading of single cinematic frames, zooming in for what they can reveal of the whole of which they form a part. Rombes poses the question, to what extent can statis and text illuminate a medium of movement and light?

In 10/40/70, Rombes explored whether using periodic, arbitrary frames could summarize the major theme of a film. Pushing the focus further, in The Blue Velvet Project, he has embarked on a year-long close reading of individual frames from that film, each frame serving as the basis of a mini-essay. The frames in both of these projects are not, however, viewed in isolation; the interpretations rely on a knowledge of how the frames fit into the whole, technically, visually, and thematically.

With Do Not Screen, Rhombes invites the reader into the process, widening the aperture but narrowing the lens. For despite receiving 12 real frames of film, in the real mail, the participant receives somewhat less than it would seem. To evaluate a clip, even a short one, you need to see it in motion, either in real time or in your memory; and you need as well to see the whole of which it is a part. A “still” is only still in relation to the moving whole. Participants are encouraged to submit their own mini-essays, along with their clip code. Crucially, comments left by the viewer on Do Not Screen (and unlike the other projects) precede incorporation of their clip sequence into the filmic puzzle; in this, Rombes tries to see what, if anything, of value can be gained from a still sequence, devoid of other context.

[Contextless clips from Decasia: The State of Decay, reassembled by Bill Morrison, 2002]

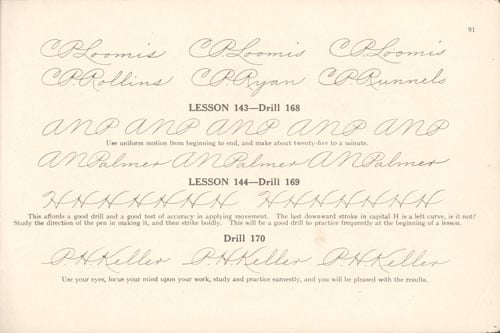

To what end? Ah yes, the mystery. A good part, perhaps the central part, is to distribute the joy of discovery. After emailing interest, participants receive a package in the (real) mail, containing a 12-frame film snippet, along with other analogue materials, perhaps discovered, perhaps re-created. The snippets and fragments certainly have the look of being old. Paper is perhaps easy to age, to the non-art-restorer’s eye. But that penmanship! The Palmer Method is no longer enforced, or even fully embraced. But the Palmer precision loops and whorls and carefully connected c’s, r’s and e’s are unmistakeable… My documentation seemed to contain a timesheet, for a foreman and his crew of laborers, carefully notated with cents per hour, and days present, in cursive pencil on a pre-computerised card.

[Precision loops and whorls]

And the final film, not omitting “do not screen?” The emerging scene indicates some kind of community celebration, with farmers’ families dutifully assembled in pressed cotton and serious expressions, perhaps to commemorate Memorial Day; perhaps for something more local, and specific. Interestingly, the footage lightly reflects on itself, as a cameraman and assistants wink in and out of frame at several points.

Like so much work with the gap, should the entire found footage be reassembled, the result would be somewhat less than the evocative fragments viewed to date. By leaving real-time gaps in the footage where the as yet unsent clips will go, shifting without transition to pans and close-ups of the community assembly, colors faded and devoid of sound, one tends to fill in more than what will inevitably be there.

Eulogies highlight some events, discard most. Memories cherrypick, fade and embellish, for better or worse. In its incomplete, half-constructed state, the film so far gestures towards an era before the transition to midwest agribusiness was complete, references a less media-savvy time, highlights one of those remarkable unremarkable days in the life of ordinary citizens, which, as Thornton Wilder both celebrated and cautioned against in Our Town, one may not revisit without complication. An ordinary memory, perhaps so ordinary as to have been forgotten by those who were there, who in any case are likely no longer here, even the children — an ordinary memory which is important only because everything is.

Emily: But first: Wait! One more look. Good-bye , Good-bye world. Good-bye, Grover’s Corners… Mama and Papa. Good-bye to clocks ticking… and Mama’s sunflowers. And food and coffee. And new ironed dresses and hot baths… and sleeping and waking up. Oh, earth, you are too wonderful for anybody to realize you. Do any human beings ever realize life while they live it — every, every minute?

Stage Manager: No. (pause) The saints and poets, maybe they do some.

Emily: I’m ready to go back.

[Thornton Wilder, Our Town, first performed 1938]

And yet, in between the process and the result, there is something that meets the expectation of mystery. As each code is entered into the site, those frames (previously digitized) are activated in the timeline. The timeline can be viewed in its state of incompletion, with the unactivated frames left blank — but crucially, with the missing timespans preserved. This simple construction allows for inconsistent gaps, in a rhythm just odd enough to be provocative.

One may be reminded of a certain intriguing conversation between Angela Bassett and James Woods towards the end of Contact: “The fact that it recorded static isn’t what interests me. What interests me, is that it recorded approximately 18 hours of it.”

[Contact, dir. Jodie Foster, 1997]

By leaving space for the time, Do Not Screen displays the gaps and preserves the possibility spaces. The ideal outcome may be something that is beautifully broken — enough participants to surround the gaps, but not too much to fill them in.

All stills are from Do Not Screen.

See the film so far at Do Not Screen dot net.

To receive a clip and participate, email Nick Rombes.

Other projects mentioned: