Linda (16)

By:

October 6, 2011

HILOBROW is proud to present the sixteenth installment of Karinne Keithley Syers’s novella and song cycle Linda, a hollow-earth retirement adventure with illustrations by Rascal Jace Smith. New installments appear every Thursday.

The story so far: Linda has been traveling across the country, which is empty and covered in dust from a hole punctured by a comet she herself called down to earth. She has visited cites and great natural monuments and even toured movie theaters in small towns in Pennsylvania. She has found the one waitress awake in the country, and had pie, and been told to drive to California, and so she is driving to California now.

28.

The blueness of the sky was the first sign, or really not the color itself but the flat pervasiveness of it. Sometimes, driving, Linda sees the sun, sees it cut across the space, sees the shadow of the van as she interrupts the light, rolling across the country. But then the whole part above the trees and houses flickers and beams a single color, and although there is ample light, it is so perfectly even that it seems not to come not from anywhere, seems not to travel at all. Once people thought that a substance called ether filled all empty space, a tiny vortical festoon strung up against the void, an affirmation of substance, of pattern, but that was before they knew about how waves of light and sound travel across emptiness. When the blue, or purply-grey, or orange flickers onto the sky and the slant of light disappears from the landscape, Linda knows that something is happening like the globe reasserting itself, expanding somehow, leaked out beyond its initial course and enveloping the continent. And this reassertion somehow returns the world to an earlier governance, a governance of concepts or the picture plane. If she had gone to the Cloisters when she was in New York City, she might have seen medieval paintings in which the sphere of any action was limited to a shallow field, behind which usually sprung a bank of trees or a boulder, and behind that an ornate and vertical plane of blue, red, and gold diamonds, without depth or contingency, achieving instead a kind of pure state, a state without distance, an eternal copula.

Linda has not completed her itinerary, is not ready for the reassertion of whatever that was that went on when she woke in the kitchen and walked in the globe (although she would like to see dog-Linda, very much). In fact she quite enjoys driving around an empty country, sight-seeing, the only one awake in the land, freed of all tertiary commitments, freed of the ruts and pleasures too of the habits she built her own life on, a sequence of arbitrary whims that become structural, became normal. When she said to me, in Knoxville, “I feel like I just graduated high school, like I could do anything I want,” she felt her own life had arrived at a section ending, and that she had been cleared, had met her commitments, had performed according to plan, and was now approved to move freely. Part Two: Retirement. Gone fishing, please call back. And so I began imagining Linda because I wanted to imagine her moving cross country in delighted freedom, wanted the country of her retirement to be replete, abundant, worth the deferral, wanted every self-concept of the limitations of her own particular life to be null for a season, worked to envision for her the gift of this season. In the vision, she drives along rocky palisades and country highways bordered by wildflowers or winding into mountain passes of very tall fir. In the plains she sees weather, sees it almost as an explanation of itself, sees from a long way off a storm sitting like a tall hat on a town, and rain clouds reaching down spindles like hands of some kind of loom. Sees countless houses she can imagine herself living in, sees the way the land’s curve becomes flat becomes cut becomes strange and rocky and lunar, and then glides down to the sea. She drives through redwood forests, drives alongside low rocky rivers, has a season of seeing, where seeing is understood as the greatest possible occupation, a sufficient and resplendent relationship to a sufficient and resplendent world.

Linda is pulled over on the side of the road, at an overlook in Colorado, eating the last of the sandwiches from the Midway diner and boiling water on a small cookstove. The sun is directly overhead; the air is thick with dust. She is looking back at the Great Plains, from which the hills she is now on rise up as clearly as the cardboard hills in her fourth grade plate tectonics diorama, a perfect abruption. She has never actually been to the West before, and finds herself astonished at the exactitude of this continental divide. Everything around her is coated in a thick dust, except the quaking aspens, whose leaves have shaken off the coat to set their silvery green circles against the grey.

The sun is hot and Linda feels drowsy, so she pulls a chaise lounge out of the van, positions an umbrella over her face, and goes to sleep. On her way into sleep she dreams shallowly of a small stair. She is running and doesn’t see it, and trips. A shock of electricity moves through her leg as it jerks her awake. She sees the sky blink into blue and then passes out again. On the fringe of sleep she hears a loud thunk, the sound of a massive power switch cutting out by force. She passes directly into a deep sleep, bypasses the dreamtime.

When she wakes, she is in the kitchen. She hears the dull hum of the refrigerator and the familiar flap outside the windows. Beyond the glass panes of the door she looks for the freeway, but it isn’t there. She thinks she sees mountains but when she rubs the glass there is nothing but fog. She thinks she hears a strand of music coming from the next room, past the door. The television is on. It’s the PBS documentary on Josephine Baker again. She bangs on the door and asks who is there, but no one answers. So she fixes tea and lies down against the fridge, falls asleep again. In her sleep she dreams of eggshells, a collection of quail eggs and turkey eggs and robin eggs taken delicately up from cast off nests, or fallen beneath the trees of Tennessee. She sees her shoes and her fingers, fingers of a twelve-year-old. Again she dreams of tripping and again her leg jerks violently, half-waking her, and she finds she is leaning against a tree in the globe. She falls back into sleep and again when she wakes she is in the kitchen.

What happens in the kitchen is what always happens in the kitchen: the door opens and she walks through it down the concrete path to the street, and just as she steps, where the sidewalk should be is soft underbrush, and beside her dog-Linda, and she is in the globe, walking. But this time everything in the globe is blue. The trees, the sky, the dirt, her shoes, even dog-Linda is blue. And this time something is strange with the trees. Trees of high altitudes mix with desert trees, which neighbor trees only found in Maine, ancient redwoods, trees that are strictly shrubs, trees only remembered by old people, and trees only visible from a distance. The ground is covered in blue mushrooms and fallen trunks are everywhere rotting blue rot. Dog-Linda jumps over the trunks, trots off and returns, licks Linda’s hand and leads her forward.

They walk and walk until they reach a clearing, a large field in which a small portion of a town has been built, almost like a film set. Dog-Linda leads Linda down the streets, and as she gazes into the windows she recognizes the town as one she has already driven through, a town she liked somewhere in Kansas. From the moving van it was romantic but on foot she finds the town immeasurably sad. She goes up to windows, and beyond the spray of dust that has come through the cracks and the spaces under doors, she sees people sleeping, through every window, people curled on beds, on couches, sees pets sleeping. Even the spiders hold still. Every house is filled with them. She bangs on the doors but no one stirs. Dog-Linda licks her hand, and leads her through the small, partial neighborhood until the street gives way again to forest.

They continue to walk. When it is time to sleep they sleep together on the floor of the globe, Linda lying on her side and dog-Linda curled up against her, head pressed down on her thighs, a lookout. One day they come to a body of water, a pond with long arms that is almost still. Walking along the length of the arms they both see at the same time a tall white dog, long haired, sitting on the opposite bank, looking out at them. Next to the dog is a man sitting cross-legged and apparently meditating. Something about him reminds Linda of an old photographer friend from Nashville and the sitting man’s image blinks and is replaced by this friend. The dog remains the same.

It takes several more days of walking to find their way across the water to the man, or rather the dog. They are met in the woods by the white dog, and after this dog and dog-Linda have done their sniffing, they both turn to look at Linda, and then walk together, ahead of her, side by side, until they come upon the meditating man, who still looks exactly like Linda’s photographer friend Daido, although she is quite sure that Daido’s image is hanging in front of him, somehow, not really his own image. Or maybe Daido is hanging in her eyes, translating the incoming form into this convenient alternative. Anyway she sits with him, can feel him in particular, present, not Daido but someone specifically else. The dogs wait on either side. After a long time, someone brings her food, addresses the sitting man as the colonel, confers somehow in silence, and then quietly disappears. The man doesn’t move, but Linda can hear him breathing. Something thumps in her guts, then settles. She closes her eyes.

The images the colonel sends are of dust, but not of the dust she has seen, spewing out of comet-made holes in the earth like so many whale jets and blanketing the sleeping continent. It is human dust she sees. He sends images of bodies sleeping, pets sleeping, children sleeping. These images hold in her mind, each one playing like a time-lapse movie, as the bodies slowly turn to dust. At first the only sign is a slight sinking in the chest, then a falling open of limbs. Eyeballs sluff out of sockets, skin sinks then greys then particulates. One by one these images play across her mind’s eye. She is sure they come from him. One by one each house she has passed in her long drive announces itself in her mind’s eye, opens doors and curtains to reveal its sleeping inhabitants, who one by one crumble in front of her. She feels dog-Linda pressed against her side, solid and living. Feels the colonels hand on hers, for a moment. And then he shares the map. It shudders into her vision like a spent fluorescent light. She thinks she might recognize it from a book she used to read to her daughter. It is a map of the interior of the earth. In the map the world is hollow, and in the hollow there is no dust.

29.

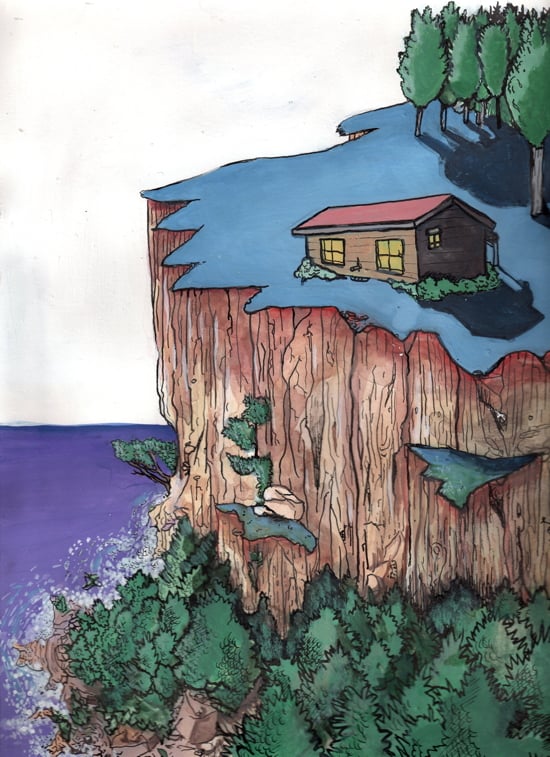

When Linda left the colonel she returned to the van, with dog-Linda. They drove in silence to the sea, from Colorado into Utah and from Utah into Nevada and from Nevada into California, and through California to the sea, where there is no more dust, and at the sea they get out and start walking, north up the coast. Just as before, dog-Linda runs off, then circles back, but now the periods of the dog’s absence are growing longer. By the time Linda comes upon a small, lighted hut, she has not seen dog-Linda for a full day. Before the hut was visible she heard the music being played there, from speakers pointed out and casting their sound over the land. Sometimes the coastal wind is so loud that the voices go away completely. But even thinned and knocked sideways, she recognizes the songs out of the sacred harp songbook, the songs that she and Al sang the day they dropped me at the airport and went to the singing, in a hollow in the hills.

When she arrives at the hut on the coast of the land, where the singing is playing out of speakers, there is a man standing on the threshold, watching her approach. He’s drinking something, something he must have brewed himself. She approaches him slowly. He squats on his haunches, squints. When she is in range he puts out his hand and introduces himself.

Linda? I’m Sal.

Hi Sal, she says, cautiously. His voice is the color of gravel.

I’ve been waiting, he says. So gravelly the sound doesn’t even travel, like he could narrate her own mind, from perfect closeness.

Sure.

Above the door is a small lighted sign that reads KHLO.

The interview is Linda’s first. While the music is still playing, he shows her how to put the headphones on and adjust the volume and where to put her mouth in relation to the microphone. When the song ends he moves the sliders up on the great board in front of him, and begins:

You’re listening to KHLO, on the short waves from an undisclosable location amidst the dust, and I just want to say to you out there that it is statistically just short of miraculous that you are listening.

You. You are listening, aren’t you?

Miraculous.

You know, there aren’t many listeners out there, anymore. But we’re working hard on the signal, to make it down there, since the out there no longer calls. All you listeners down there, you are a miracle. Good job. Now I don’t know why I keep saying “we,” since I am the solitary being working here at KHLO and trying to get you a signal. We are not working on this signal, except insofar as I can imagine you there, working on your reception, and so wagering, I think you could say, on a we that is working.

We are working, are we not, friends?

But oh what a blessed relief, my friends, friend?, friends, let’s say friends, that something very rare, something I’ve been hoping would happen, but not hardly believing it would, is happening. Which is to say, I’ve got company.

He pauses. Yodels a little happy variation of the one of the songs he’s been playing on records to the dust. Ends. Resumes.

Yes I’ve got company right here in Little River. So let’s all give a big welcome to a friend from Knoxville, a Knoxville girl, come a long way.

And Linda says, thank you, and she means it because she feels amazing, speaking into this microphone, feels glorious.

Thank you. It’s nice to be company. It’s been a while. I’ve not even had the company of my dog friend, says Linda, well for most of the time, and she’s gone now.

(Somewhere underground Bessad’s hand moves to dog-Linda’s head. Dog-Linda’s head presses Bessad’s hand.)

Well that is hard, says Sal, whistles a dog call.

But Linda, he resumes, Linda – what I want to know is, how did it feel?

Linda speaking soft: I felt at first like I just didn’t even exist. Like I had been packed in ice, as if I’d be useful in the future but for now I had better not bother anyone, and since I would most likely bother someone, it would be better I was packed up. Not that I could point to any event like where someone actually packed me in ice or said anything mean. It was just a feeling, a feeling of lingering uselessness. It was more like, when I started on this, when I started walking, my body felt like it had gone through a freeze, a freeze I couldn’t remember happening.

And I felt distinctly like my body wasn’t my own, didn’t belong to me. Like even my dreams weren’t my own, like they came into me from another head, somehow. That I would be awake and moving without having made any of it myself, even the walking I didn’t make myself.

Now Linda, wait a minute, says Sal. More gravelly than imaginable. Wait just a minute Linda, you mean you were walking without doing the walking yourself? Because pardon me if I am mistaken but I think you had to walk yourself here.

Yes, says Linda. I did. Walking, then driving and then more walking.

Yes, but I learned how to walk again. I invited myself back.

And when did you get the idea that you were the one who had to do the inviting, Linda?

After I met the colonel, she says.

(Somewhere underground this both thrills and terrifies a room of listeners.)

I found him at the water. Or really the dog found him. Or found his dog. The colonel has a dog, an enormous white long-haired dog. We saw it across an arm of water, like it was standing sentry on a ghost palace or something. Like it should have been made out of jade. Or white jade. Is there white jade? That doesn’t make sense. But you get my idea. It was fantastic, this dog, it was a beautiful dog. I would wake up and the dog, my dog friend, not this white jade ghost dog, would be waiting for me, and we would go out walking, looking for the other dog.

And he had summoned you? What did he say?

He didn’t say anything.

He didn’t?

No. I remember the dogs sat on either side of him.

And how long did you sit there?

A few days, I think.

Did you eat?

Yes.

Sometimes a man brought me food.

The colonel’s assistant?

I don’t know. But there was a man who sometimes brought me food.

Can you describe him? Oh, maybe mid- or late-40’s. Navy wool sweater. Boots, sort of an ex-military farmer I think. Very dark hair with a bit of grey in it. Slender.

And did he ever say anything?

No, he just brought food.

Normal food?

Yes, sandwiches, broth, that kind of thing.

What about the colonel. What did he look like?

I can’t say what he really looked like. In my memory he looks exactly like a Japanese photographer I knew a long time ago in Nashville.

So he was Japanese?

I don’t think so, but I can’t say. In my mind the image has literally been overwritten. I have no idea what the colonel looked like. Every time I try to imagine him, I see my friend Daido.

And what happened?

Well we just sat together. I didn’t get tired at all. It was a feeling maybe like what hibernating feels like. After a while I began to see things.

You hallucinated?

No, I believe the colonel was sharing images with me. Images? How was he sharing them? By thinking hard about them. I can’t really explain it more than that. But I felt that it was he, showing them to me. And what were the images of. They were quite-

Yes?

Quite awful. Linda watches again as jaws soften and collapse. As dog paws sift down into a wide pool of dust, and blow away.

They were –

Yes, go on.

They were quite gruesome.

They were of the war?

No.

The fires?

No.

The dust?

Yes.

Why do you think he showed these to you?

I don’t know.

What did he want you to do?

I don’t know.

So he didn’t give you an assignment or any direction?

In a way, but I didn’t know what it meant.

What what meant?

The last image was a map.

Of what?

It was in a children’s book, something like burrows or tunnels in space.

Outer space?

I don’t think so.

And then?

Then I woke up in the kitchen.

And you didn’t know anything.

Nothing. I forgot all of it. At first I didn’t know anything, I didn’t know why I was there, or that I had been there before.

What about the eggshells.

What?

You remember the eggshells?

What? No.

What?

No there were no eggshells.

You don’t remember the eggshells.

No. And then apologetically: There are no eggshells. There never were.

Sal blinks. Swallows. Looks at her hard.

There were no eggshells?

No.

So what were there? If there were no eggshells.

We make them disappear, you see, says Linda feeling like she knows, she knows what she’s saying, she can say and mean a sentence: by saying it. We renounce all eggshells. We refuse all eggshells. We reject. I reject. I reject eggshells.

KHLO, broadcasting from an undisclosed location amidst the dust, we know to be actually just next to the sea on the northern coast of california, and just a little ways inland, just five or six miles, not far enough to lose the sea air but far enough to be quiet, there is a forest, a pygmy forest, and under this forest there is a tunnel, covered by something very simple like a manhole grate, one of the oldest tunnels, the first ones prepared, a tunnel reaching directly down with a ladder fitted into the dirt by which one descends, away from the surface, away from the light, away from the dust and away from the sleeping, one descends. And so Linda, who has renounced all eggshells, who has left Sal to play records of the singing, who has walked the five miles in the hovering grey, directly to the manhole as if she always knew it was there, as if she always meant to walk here, pulls back the cover, slides her body down, and descends, which is the end of part three of Linda.

And now, listen to the next song in the Linda song cycle, finder:

FINDER

NEXT WEEK: How it works in the hollows. Stay tuned!

Karinne and HiLobrow thank this project’s Kickstarter backers.

READ our previous serialized novel, James Parker’s The Ballad of Cocky The Fox.

READ MORE original fiction published by HiLobrow.