Dead Media 2.0

By:

October 5, 2011

It is old news on the interwebs that the retro technology of scrolling has replaced the once new (and now perhaps intermediate) technology of the page-filled codex.

[Medieval Helpdesk, from “Øystein og jeg” on Norwegian Broadcasting (NRK), written by Knut Nærum, 2001]

Despite the occasional ebooked animated page curl, or the sequenced click for next page (8,9,10… 99) that some news and magazine sites still retain, scrolling is the default action on the web. (With clicking/teleporting running a close second, and the touchscreen zoom bringing up the rear…) A page can be as long as it needs to be, and often is.

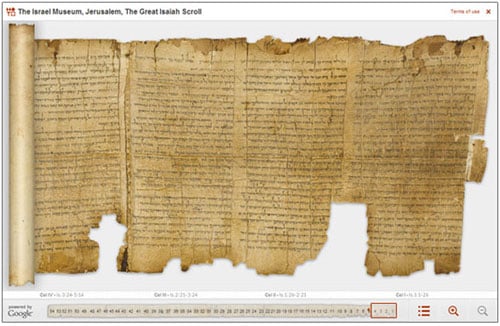

But what’s very, very old is new again. I am referring, of course, to the Dead Sea Scrolls, whose digitized avatars have finally emerged where they were always meant to be, online. Aided by Google, and hosted by the Israel Museum in Jerusalem, certainly not all, but several significant scrolls are available via the website. Selecting one opens an interactive modal window, cursor positioned expectantly to the far right, inviting the viewer to horizontally scroll to one’s heart’s content.

That’s viewer, not reader — there is a significant barrier to comprehension. Not only the language barrier, although that is significant enough:

Hebrew is the most common language, though a small number of scrolls are written in Aramaic, and a few in Greek. The most common script is the Jewish script, also called the ‘Assyrian’ or ‘square’ script, which was widely used from the sixth century BCE on. However, about 14 biblical scrolls are written in the ancient Hebrew script, and many texts use a cryptographic script, combining mirror writing and a mixture of Jewish, ancient Hebrew, and Greek scripts.

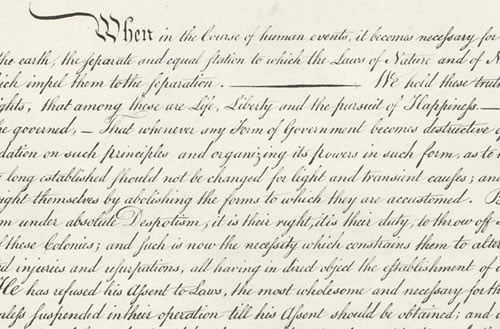

There is also a significant technological barrier — that of handwriting. Handwriting presents a different picture of a text; these days, literally a picture. With typing ubiquitous, cursive becomes a graphic element, a drawing. A handwritten page is difficult to actually read: one can, with effort, pick out an identifiable word or phrase, but then one tends to zoom out and consider it as a visual whole for a moment before moving on — to the typewritten transcript, or simply elsewhere.

[Detail, cursive script, Declaration of Independence]

But the changes in perspective extend beyond cyberspace, back to the physical objects themselves.

An image on the website shows an intriguing in situ display from the museum. A scroll is displayed in the round — but unlike panoramic paintings, which encircled the viewer with battles and scenery, the scroll is presented on the inside of the imagined cylinder, so that the viewer, walking, may encircle it.

[Panoramic photograph of Cornell University, Seth L. Sheldon, 1902]

Which either places the scroll in the position of the sun, in the orrery of text and comprehension — or it places the viewers in the position of framing and containing the text within their own walked/lived experience.

[The Grand Orrery, Benjamin Martin, 1764-1767; Collection of Scientific Instruments, Harvard University]

In this, the presentation echoes the challenges posed by some of the scrolls’ more controversial content — do they destabilize the established order by offering a new point around which to orbit, or do they offer one more interpretation in an undead sea of interpretations, leaving us, as ever, to attribute and collate the difference?

We will leave it up to you to meditate upon which gloss offers the correct interpretation. And time will tell whether the scrolls’ digitally coded containers will prove as robust — or as problematic — as the cave-dwelling urns of their previous storage facility.

See the scrolls online at The Digital Dead Sea Scrolls