Radium Age Cover Art (1)

By:

September 28, 2011

Some of the most gorgeous, evocative, and strange science fiction art you’ve ever seen comes from the covers of novels written between 1904-33, in what I’ve named sf’s Radium Age. I can’t afford first editions of many Radium Age sf novels, but I’ve collected images of their dustjackets and “boards” (the paper- or cloth-covered stiff cardboard forming a book’s covers). The following 10 sf novels boast some of the most thrilling and evocative board and dustjacket) illustrations and design from the era.

[This essay was originally published at io9, in December 2008.]

JOSH GLENN’S *BEST ADVENTURES* LISTS: BEST 250 ADVENTURES OF THE 20TH CENTURY | 100 BEST OUGHTS ADVENTURES | 100 BEST RADIUM AGE (PROTO-)SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST TEENS ADVENTURES | 100 BEST TWENTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST THIRTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST GOLDEN AGE SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST FORTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST FIFTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST SIXTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST NEW WAVE SCI FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST SEVENTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST EIGHTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST DIAMOND AGE SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST NINETIES ADVENTURES (in progress) | 1994 | 1995 | 1996 | 1997 | 1998 | 1999 | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | NOTES ON 21st-CENTURY ADVENTURES.

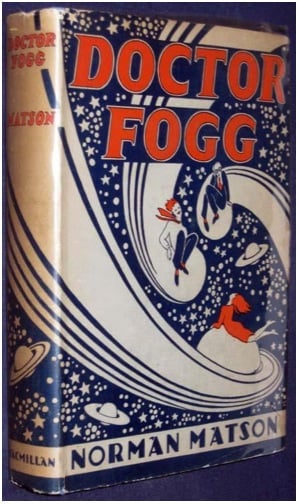

1. Norman Matson’s Doctor Fogg (New York: The Macmillan Company, 1929). A shy and retiring Chicago scientist manages to communicate with an advanced alien civilization, whose scientific secrets he refuses to share with Earth’s flawed political powers; and he accidentally “broadcasts” a gorgeous naked blonde alien with whom he falls in love. What does the fun dustjacket illustration have to do with it? Nothing! But I love the speeding meteors, which converge cozily at the center of the image; the void of space absolutely chock-full of stars and planets; the awkwardness of the gentleman at top right compared with the insouciance of the woman beneath. I also admire the crimson-orange/navy blue/silver color scheme. Making the characters’ hair, the men’s neckties, the woman’s dress the same color as the slightly italicized title? An inspired decision. NB: The board illustration is also super-cool: it’s a silver planetoid with the words “Doctor Fogg” inside.

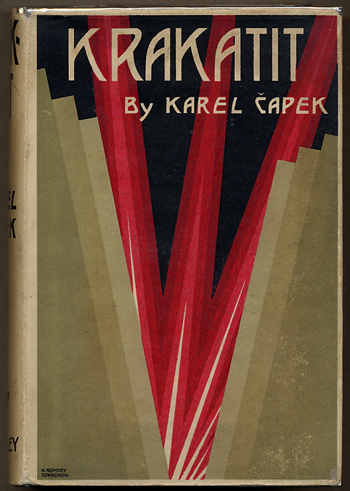

2. Karel Čapek’s Krakatit (London: Geoffrey Bles, 1925). An English translation of the Czech author’s 1924 novel. A scientist discovers the most powerful explosive ever, but he refuses to share it with (see above) Earth’s flawed political powers. The Art Deco jacket design captures both the excitement and terror of such a discovery. The stylish typeface says, “Not to worry, the future is awesome!” But K. Romney Towndrow’s artwork — an explosion rending the very planet in half — says, “Yes, worry.” Still, this is a satire, so we’re not encouraged to take things too seriously; the illustration kinda reminds us of limelights in a canyon of skyscrapers. It’s as though we were approaching a 1925 Hollywood movie opening, perhaps Marion Fairfax’s The Lost World. Fun facts: The book was adapted as a 1947 movie (d. Otakar Vávra) and a 1960 opera (Václav Kašlík); both are supposed to be tremendous. The 1925 US edition of Krakatit has a more restrained, but still fun, jacket.

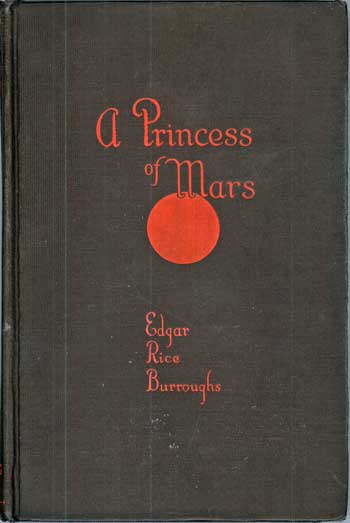

3. Edgar Rice Burroughs’s A Princess of Mars (Chicago: A. C. McClurg & Co., 1917). I’m not impressed with the original book jacket illustrations for Burroughs’s Barsoom series. Sure, they feature lone heroes confronting hordes of alien warriors, not to mention half-naked damsels menaced by multi-limbed aliens, but… Frank Frazetta’s later work on the same titles demonstrates just how tame the original jacket illustrations were. They make the swords-and-sandals-in-space genre feel middlebrow and uplifting, which is precisely what we hi-lobrows do not enjoy. Peel away the Barsoomian jackets, though, and you’ll often find more compelling boards underneath. A Princess of Mars was Burroughs’s first published story — it was serialized in 1912, under a pseudonym — and everything great about his writing is captured here. That Arts & Crafts typeface, so pseudo-medieval and chivalrous! That red planet, so mysterious and alluring! Stop the world, Edgar, I want to get off.

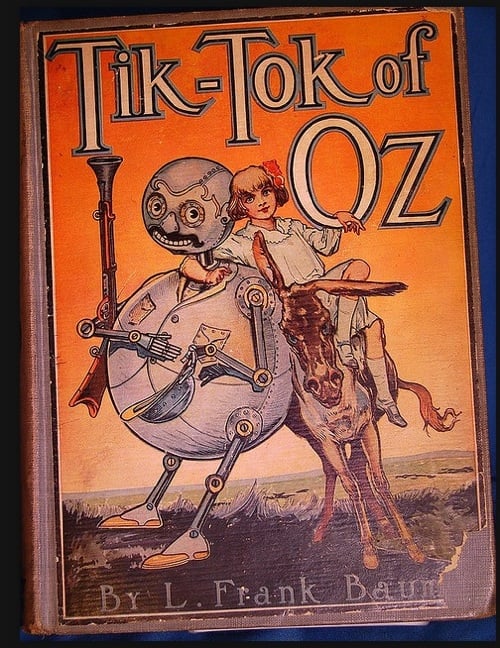

4. L. Frank Baum’s Tik-Tok of Oz (Reilly & Britton, Chicago, 1914). Illustrated — like 39 of the 40 canonical Oz editions — by John R. Neill, Baum’s picaresque concerns the efforts of the Shaggy Man (a proto-hippie who disdains all possessions except his Love Magnet) to rescue his brother from the Nome King. Tik-Tok, a copper-bodied clockwork man, first appeared in Ozma of Oz (1907), then starred in a 1913 stage musical. In this book, despite Neill’s sweet, startling dustjacket illustration, Tik-Tok is (as ever) an emotionless though fiercely loyal servant. Exactly like Karel Čapek’s flesh-and-blood “robots.” Fun fact: Though often described as the first robot to appear in modern literature (if you don’t count living-metal creatures, like the golden maidservants who attend Hephaestus in The Iliad, that is), Tik-Tok was preceded by Edward S. Ellis’s Steam Man of the Prairies in 1868.

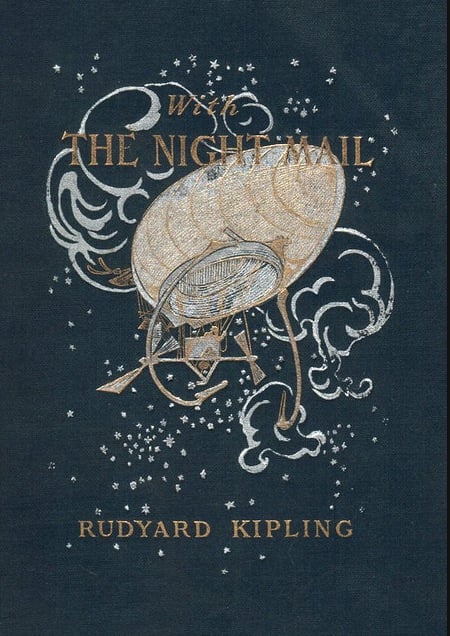

5. Rudyard Kipling, With the Night Mail: A Story of 2000 A.D. (New York: Doubleday, Page & Company, 1909). This SF novella by Kipling – best known for The Jungle Book, Kim, and the Just-So Stories – first appeared in McClure’s magazine in 1905. In 2000, lighter-than-air craft traverse the globe; the plot follows a mail dirigible on its adventures. Kipling got so excited by his own nerdy vision that the book’s appendices include ersatz instructions to aviators, not to mention advertisements for imaginary dirigible and aeronautical products. Detailed illustrations and pictorial endpapers make this a gorgeous production, indeed. “A beautiful object, most strange and peculiarly inspiring,” writes one rare bookseller, of the 1909 Night Mail. The same could be said of the gilt-and-silver zeppelin that materializes — Millennium Falcon-like — from the star-spangled indigo depths of the book’s cloth-covered boards. Wow!

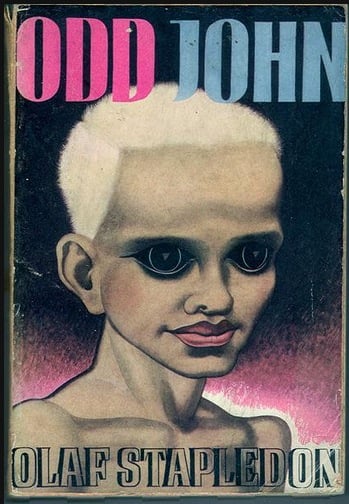

6. Olaf Stapledon’s Odd John: A Story Between Jest and Earnest (Methuen & Co., Ltd., London, 1935). Perhaps my favorite Argonaut Folly fiction, Odd John concerns the efforts of an international band of teenage and twentysomething “supernormals” (or “wide-awakes”) to form an island colony, where they can devote themselves to “world-building” (“individualistic communism,” not to mention the founding of a new mutant species) and “intelligent worship.” The jacket illustration captures Stapledon’s notion of the titular John: half-child and half-philosopher, ruthless but not malicious, “a creature which appeared as urchin but also as sage, as imp but also as infant deity,” a fallen angel with a face that is “half monkey, half gargoyle, yet wholly urchin, with its huge cat’s eyes, its flat little nose, its teasing lips.” Cue David Bowie: “Look at your children/See their faces in golden rays/Don’t kid yourself they belong to you/They’re the start of a coming race.” Homo Superior, that is.

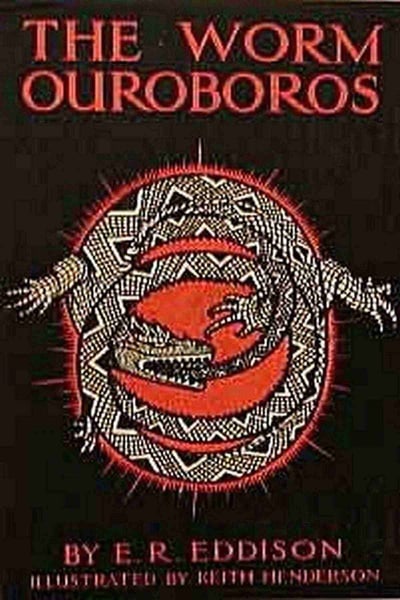

7. E.R. Eddison, The Worm Ouroboros (London: Jonathan Cape, 1922). More admired than read, Ouroboros is a linguistically adventurous saga recounting the infinite war between the king of Witchland and the lords of Demonland… on the planet Mercury. Call it Nietzschean SF: somewhere out there, the author would have us believe, another world is possible, one in which the self-overcoming values and worldview of Roman, Arab, Germanic, Japanese nobility, Homeric heroes, and Scandinavian Vikings will never be corrupted. (As Lord Juss puts it: “For better it were we should run hazard again of utter destruction, than thus live out our lives like cattle fattening for the slaughter, or like silly garden plants.”) The end of Eddison’s novel is also its beginning, hence the title and Keith Henderson’s heavy-metal jacket illustration — a snake devouring itself tail-first. Like they so often do in medieval engravings, Celtic sculptures, Egyptian scrolls, Aztec glyphs, and on Agent Scully’s lower back. Wish I could afford a 1st edition.

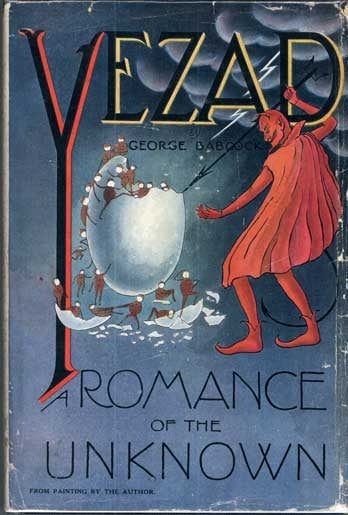

8. George Babcock, Yezad: A Romance of the Unknown (Bridgeport, Conn. & New York: Co-Operative Publishing Co., Inc., 1922). Almost as much as I love the Satan-vs.-Martians jacket illustration (“from painting by the author”), I love the novel’s description: “Highly eccentric romance of reincarnation, which includes an account of the colonization of the Moon by near-perfect humans of Mars and the unhappy circumstances of the descent of our ancestors to Earth.” Mars, it seems, was once a technologically advanced utopia. Then, 20 million years ago, it lost its atmosphere, so the Martians relocated — but, in doing so, degenerated into our beast-like ancestors. (Isn’t this the plot of Jack Kirby’s The Eternals? And Scientology?) As for the devil on the dustjacket, the occult point of Babcock’s novel is to inform us that we are divided creatures, within whom Bonality and Malality (good and bad aspects) struggle. Moral: Don’t let Malality triumph, or it might break Martian-filled eggs with its pitchfork.

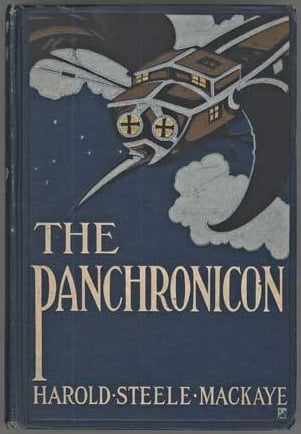

9. Harold Steele Mackaye, The Panchronicon (Scribner, New York, 1904). I’m informed that The Panchronicon concerns a pair of New Hampshire spinsters who are given the opportunity to travel through time via a solar-powered airship-thing from the 27th-century. See, first you fly the Panchronicon to the North Pole; then you orbit the Earth widdershins (anti-sunwise, like Christopher Reeve does in the 1978 Superman); and presto, you’re in 16th-century England, where you’re able to disprove the Bacon-was-Shakespeare theory. Meanwhile, your drunken shipmate, Copernicus Droop, can attempt to patent the phonograph and the bicycle. Sounds fun… but as you’ve perhaps intuited, I’m not convinced that the book is actually worth the effort of reading. Still, the cover board illustration is awesome. If this is what 27th-century time-travel technology looks like — part houseboat from Arthur Ransome’s Big Six, part Terry Gilliam machine, part Owlship — then western civilization is inarguably headed in the best of all possible directions. Sign me up.

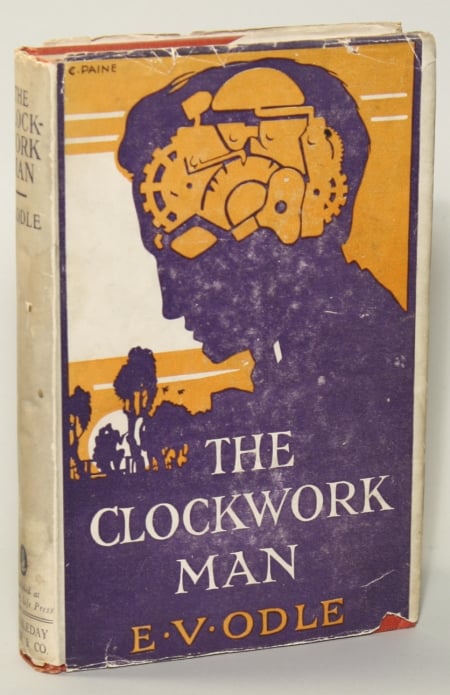

10. E.V. Odle, The Clockwork Man (London: William Heinemann Ltd., 1923). “Of the many works of scientific romance that have fallen into utter obscurity,” writes Brian Stableford, in Scientific Romance in Britain, 1890-1950, “this is perhaps the one which most deserves rescue.” Eight thousand years from now, advanced humanoids known as the Makers will implant clockwork devices into our heads, devices which permit us to move through time and space — at the cost of a certain amount of agency. If one of these devices should go awry, a “clockwork man” might appear in the 1920s, at a cricket match in a small English village, behaving strangely. Worse, like the titular character in Philip K. Dick’s 1969 story “The Electric Ant,” the clockwork man might tinker with his own mechanism. Bad idea! NB: This book is extremely rare; I’ve never seen a copy for under $500… and that’s without the dustjacket. The illustration is like a Bildungsroman cover re-jiggered by Hannah Höch. Cool.

At some point down the road, I’ll do another round-up of Radium Age sf cover art…

In 2012–2013, HiLoBooks serialized and republished (in gorgeous paperback editions, with new Introductions) 10 forgotten Radium Age science fiction classics! For more info: HiLoBooks.

MORE RADIUM AGE SCI FI ON HILOBROW: HiLoBooks homepage! | What is Radium Age science fiction? |Radium Age 100: 100 Best Science Fiction Novels from 1904–33 | Radium Age Supermen | Radium Age Robots | Radium Age Apocalypses | Radium Age Telepaths | Radium Age Eco-Catastrophes | Radium Age Cover Art (1) | SF’s Best Year Ever: 1912 | Radium Age Science Fiction Poetry | Enter Highbrowism | Bathybius! Primordial ooze in Radium Age sf | War and Peace Games (H.G. Wells’s training manuals for supermen) | Radium Age: Context series | J.D. Beresford | Algernon Blackwood | Edgar Rice Burroughs | Karel Čapek | Buster Crabbe | August Derleth | Arthur Conan Doyle | Hugo Gernsback | Charlotte Perkins Gilman | Cicely Hamilton | Hermann Hesse | William Hope Hodgson | Aldous Huxley | Inez Haynes Irwin | Alfred Jarry | Jack Kirby (Radium Age sf’s influence on) | Murray Leinster | Gustave Le Rouge | Gaston Leroux | David Lindsay | Jack London | H.P. Lovecraft | A. Merritt | Maureen O’Sullivan | Sax Rohmer | Paul Scheerbart | Upton Sinclair | Clark Ashton Smith | E.E. “Doc” Smith | Olaf Stapledon | John Taine | H.G. Wells | Jack Williamson | Stanisław Ignacy Witkiewicz | S. Fowler Wright | Philip Gordon Wylie | Yevgeny Zamyatin

READ MORE essays by Joshua Glenn, originally published in: THE BAFFLER | BOSTON GLOBE IDEAS | BRAINIAC | CABINET | FEED | HERMENAUT | HILOBROW | HILOBROW: GENERATIONS | HILOBROW: RADIUM AGE SCIENCE FICTION | HILOBROW: SHOCKING BLOCKING | THE IDLER | IO9 | N+1 | NEW YORK TIMES BOOK REVIEW | SEMIONAUT | SLATE