Hollow Earth

By:

September 11, 2011

Hollow Earth: The Long and Curious History of Imagining Strange Lands, Fantastical Creatures, Advanced Civilizations and Marvelous Machines Below the Earth’s Surface. By David Standish. Illustrated. 303 pages. Da Capo Press. $24.95.

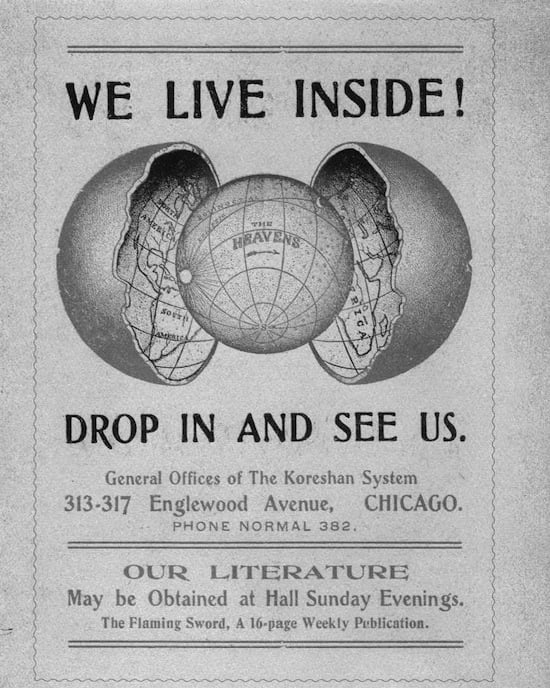

Jules Verne’s “Journey to the Center of the Earth,” a survey of mid-19th-century geological controversies thinly disguised as a ripping yarn set in a dinosaur-inhabited subterranean realm, was a best seller when it was first published in France in 1864. Five years later, an upstate New York alternative healer named Cyrus Teed had a vision revealing that the earth is hollow and that we’re all living on its concave inner surface. He eventually renamed himself Koresh, and established a thriving colony of hollow-earthers in the wilds of Florida. Then, in 1871, “The Coming Race,” by Edward Bulwer-Lytton, in which the narrator discovers an advanced civilization underground, helped give rise to dozens of science-fiction novels in which travelers penetrated the icy polar realms and descended into a well-lighted netherworld via a whirlpool or tunnel.

[This essay first appeared in the New York Times Book Review in January 2007.]

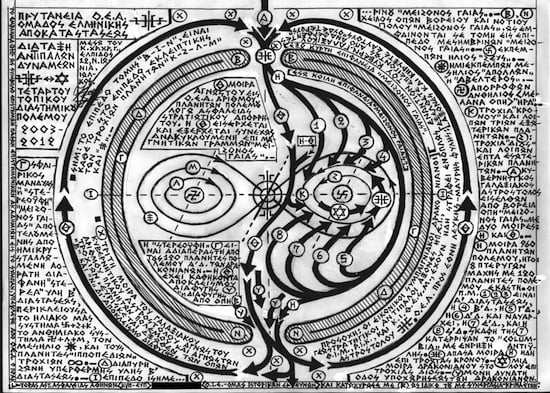

Where did the outlandish notion that the earth is hollow come from, and why did it capture the imagination of 19th-century Americans? In his entertaining new book, the journalist David Standish traces America’s hollow-earth craze to one John Cleves Symmes, a St. Louis trader who in 1818 self-published a circular gravely announcing that “the earth is hollow and habitable within; containing a number of solid concentric spheres, one within the other, and that it is open at the poles. …” The zone of ice near the poles, he argued, was merely a frozen ring surrounding a warm open sea leading to the interior.

The kookiest thing about Symmes’s theory is how believable many found it. Not that it was without a semi-respectable scientific pedigree. As Standish recounts, several pioneering modern scientists and thinkers, including the English astronomer Edmond Halley, the German Jesuit Athanasius Kircher and the Boston cleric Cotton Mather, had also advanced hollow-earth theories. (Since God would probably not have wanted to waste any space, Mather argued, an inhabitable hollow earth made perfect sense.) Symmes was less persuasive as a scientist, however, than as an advocate for a national expedition to locate the polar opening. One of his converts, an Ohio newspaper editor named Jeremiah Reynolds, joined Symmes on his lecture tour and later embarked on a failed polar expedition. Reynolds’s speeches and writings would in turn inspire the young Edgar Allan Poe to write “Ms. Found in a Bottle,” a career-launching story about a traveler sucked into an immense whirlpool at the South Pole. Poe later reprised the idea in “The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym,” which in turn inspired Jules Verne.

Standish’s research is impressive, taking in everything from the British Enlightenment and American religious utopianism to such hollow-earth literature as Jacques Casanova’s five-volume 1788 novel “Icosameron” (about a society of nudist hermaphroditic dwarves) to Edgar Rice Burroughs’s Pellucidar novels, in one of which Tarzan descends into a “Symmes’s Hole” via zeppelin. But his efforts to explain the popularity of hollow-earth-ism – a Koreshan remnant survives today with the cult newsletter Hollow Earth Insider – are weak. Standish rather lamely suggests it “can be seen as a sort of ultimate metaphysical retreat to the womb..” As for the proliferation of hollow-earth fiction from the 1870s on, it can be chalked up to the fact that writers needed “somewhere to set improbable romances now that formerly remote, unknown corners of the earth were becoming less believable as settings the more they were explored.” Ho-hum!

In the topsy-turvy America of the 19th century, in which the Civil War, industrialization, and urbanization caused all that was solid to melt into air (as a contemporary of Symmes put it), what could have made more sense than an inside-out world? Today, when utopian literature is so often dismissed as proto-totalitarian, we need dismissive explanations of hollow-earth mania like we need a Symmes’s Hole in the head. If Standish’s larger ideas are less than satisfying, it’s not because he’s wrong. It’s only because we surface-dwellers have lost the capacity to imagine that another world is possible.

READ MORE essays by Joshua Glenn, originally published in: THE BAFFLER | BOSTON GLOBE IDEAS | BRAINIAC | CABINET | FEED | HERMENAUT | HILOBROW | HILOBROW: GENERATIONS | HILOBROW: RADIUM AGE SCIENCE FICTION | HILOBROW: SHOCKING BLOCKING | THE IDLER | IO9 | N+1 | NEW YORK TIMES BOOK REVIEW | SEMIONAUT | SLATE

Joshua Glenn’s books include UNBORED: THE ESSENTIAL FIELD GUIDE TO SERIOUS FUN (with Elizabeth Foy Larsen); and SIGNIFICANT OBJECTS: 100 EXTRAORDINARY STORIES ABOUT ORDINARY THINGS (with Rob Walker).