Michael Oatman

By:

September 7, 2011

‘O brave new world,’ he began, then — suddenly interrupted himself…

Today HiLobrow commences its #longreads in art series — conversations with artists whose work demonstrates a particularly hilobrow sensibility. Michael Oatman is a maker whose work investigates a culture seemingly capering about the ambient plateau, yet reeling from the broken promises of progress. From the space race to a well-applianced domesticity, has the cone of uncertainty drained us of direction? Or is that very uncertainty the direction we thought we were looking for? Questions, questions: read on…

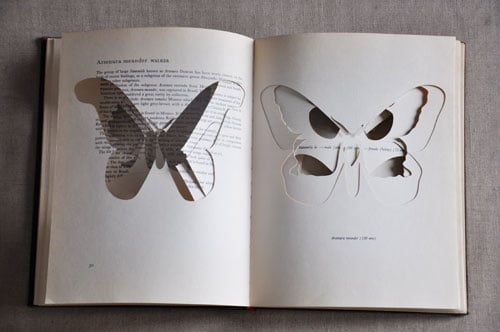

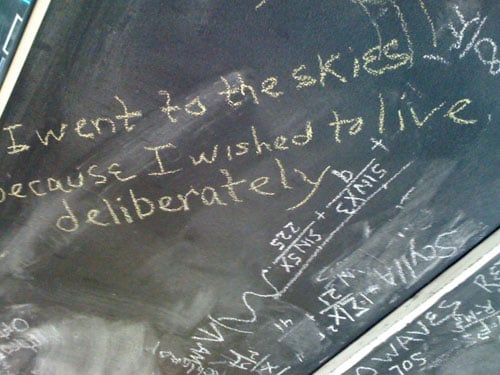

[Michael Oatman, Reenactment, 2004, Book cuttings on paper]

HILOBROW: I’d like to start with the violence inherent in the system. You love books, but to get to your imagery you have to go in with a knife and cut it out of the object, which is both violent and intimate; you’re not mediating extraction through the computer.

MICHAEL OATMAN: It’s a lot less violent than it was. I would get these books and then commit various acts of aggression on them; I’d break their spines and pull the pages and signatures apart and throw out all the pictures and pages that I didn’t want and keep the ones I did. I’d always felt that I’d been saving some images from extinction and oblivion, but the rest of the book would just be trashed, as well as all the information in it.

It was strip-mining, but then it became much more like surgery — the patient’s still alive, in various stages of peeling. About 10 years ago I received a really small cutting mat as a present. I grabbed a book and realized only afterwards that since it was a book of moths and I had just cut out all the moths, it was now a moth-eaten moth book. Without even thinking about it I had this by-product that was beautiful. It had precision applied to it in a way that, before, was just brutality.

[Michael Oatman, Beautiful Moths, 2000, holes and book pages (incised images of moths from a book entitled “Beautiful Moths”)]

H: You work with images very specifically from the 1940s to the 1970s, so there’s a certain fidelity to authenticity there. But collage is arguably the least authentic medium, because it takes things out of their original context and throws them together into another configuration, which is fairly arbitrary. What is the ambiguity in your relationship to authenticity?

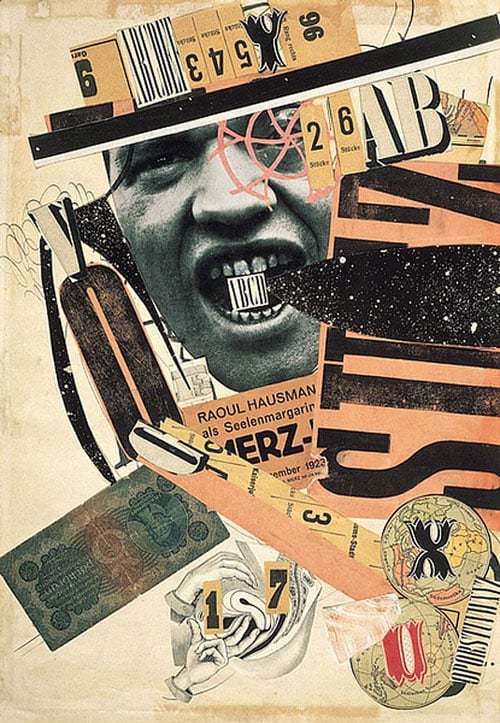

MO: I would argue it’s the most authentic way of working. What made collage possible was the mass quantity of printed material which quickly took over our lives, much in the way that the internet has taken over in this late run of technology: an engagement with some giant system much bigger than ourselves. Collage’s rise coincided with large-scale mechanized warfare; the way everything broke apart was obviously what the Dadaists, and lots of the early “ism” groups of the 20th century, were reacting to.

[Raoul Hausmann, ABCD (Self-portrait) A photomontage from 1923-24]

H: So discontinuity is authentic, to a certain kind of experience?

MO: I think so; I think it’s authentic to the experience of the city. Cities are a collage process, they’re really abrupt and fast-moving. Collage wasn’t continuing painting in the way that the Renaissance set it up — collage was all about the disjoint, and yet it still worked.

Maybe Frankenstein is the first great work of collage.

It’s like Frankenstein; maybe Frankenstein is the first great work of collage. It’s about taking medicine and skewing it, taking religion and skewing it, taking even the idea of a monster and skewing it, into a modern monster. Before, there were griffins and other hybrids, but those were supposedly created by God, right? Or evolved that way. Now suddenly you have a monster that was pieced together. That’s what is great about collage, you have to buy in to all of those disjunctures.

[Frankenstein, dir. James Whale, 1931]

H: It’s beautiful because it’s broken?

MO: Yes. And because I don’t Photoshop anything, I’m not like a painter deciding where the shadow goes; I have to work with what I have. It’s always “off” somehow. If you try to align the light sources, there are like six suns.

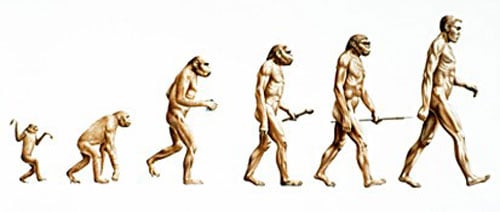

You could argue that all the source material I use is diagrammatic. Consider “the evolution of man,” which we read as a diagram about time and morphology. To look at it instead as a continuous or simultaneous moment is a great way to begin to think about all this stuff differently.

I’ve got a long-running project called A is for Dodo. Because of the dodo’s tragedy, you can’t help but see any single image of the dodo as the last one; there’s never a mate, there are never any dodo babies. So I’m trying to remake the flock. I think now I’ve exhibited it three times… I started out with about 21 dodos and then there were 40 and now there are almost 72. Every time I show it the flock grows.

H: Like giving them back their history?

MO: Or their population.

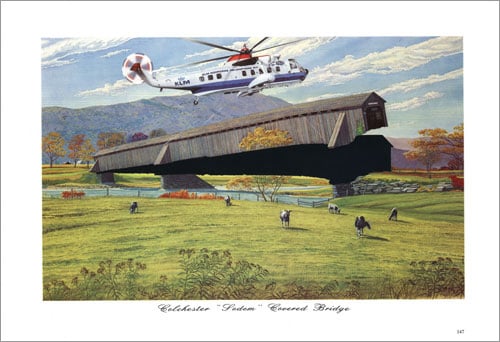

[Michael Oatman, Exurbia (more leisure time for artists everywhere), 2004, Collage and spray paint on paper on board; Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, MA]

H: Your piece Exurbia (more leisure time for artists everywhere) shows a similar time-compression. It shows rockets and satellites made and launched at different times, though in the piece they are all together.

MO: I based the image off an artist’s rendering of what orbiting the earth might look like in 100 years, like a NASA projection. It would just be filled with space garbage.

I think collage is incredibly tied to what we’ve become. It was one of the impeti for film and the internet and the idea of the interdisciplinary, and the beginning of valuing the aberration over the normative.

I’ll stop defending collage as being inauthentic; I think it’s incredibly tied to what we’ve become. It was one of the impeti for film and the internet and the idea of the interdisciplinary, and the beginning of valuing the aberration over the normative. I intend my things to look super-normal from a distance or at first glance, and then as you move into them, the breaks are psychic breaks. They’re not so much strong visual disjunctures as they are little shifts that you have to undergo in order to move from one image to the next.

H: We [Original Generation Xers and Reconstructionists] grew up in an era of accelerating progress, especially of technology, the apex of which was symbolized by the moon landing. This kind of historical moment forms a pyramid of progress, where it seems all roads are rushing to an apotheosis point. But once attained, the apex levels out into what I call the ambient plateau. “Progress” slows and there is no longer a singular direction, or a unifying overall narrative. How did you experience that dual moment in your own life? And how does it influence your work?

MO: It was an inspiring moment, and I think it became a model for some of us, in that we thought our lives were going to go that way too — that we were going to be rushing towards some unknown horizon aided by a progressive set of ideals and new technologies. We landed on the moon when I was 5. I experienced the other Apollo landings, and then saw that program wind down.

We’re going to go to Mars after this! We’re going to get jetpacks! We’re going to get solutions to hunger! And what we got was the internet.

It was one of the great disappointments of my life that I wasn’t going to be a scientist; I didn’t have the head for the math. But I ended up doing art that romances science and critiques it.

[Abandoned Remains of the Russian Space Shuttle Project Buran, 2010, via themysteryworld.com]

H: Did you feel like the cultural moment had failed you?

MO: I suppose I did. That started when I was in love with the Apollo program and thinking oh, we’re going to go to Mars after this! We’re going to get jetpacks! We’re going to get solutions to hunger! And what we got was the internet. What we got was mall culture and cellphones; things that added a lot of materiality, but at the same time let you move out into the world in ways that none of us would have anticipated. I don’t think anybody thought that we would have this much access to information so soon.

H: Maximalism seems to be a consistent formal approach in all of your work, no matter what the medium. But there’s a tension there, in that the aesthetic of technology is streamlined. In your collages you are careful to create very precise, non-painterly edges. But despite the precision, the experience of interacting with any of your pieces is “information overload,” which is a post-progress perspective. What is that tension, to you?

MO: I think I’m overwhelmed all the time by stuff that I find, the materials that I find, the news that we’re all bombarded with, and the need for finding a path through all of it.

[Michael Oatman, Man Falls to his Life, 2009, Book Cuttings on Found Architectural Gouache, 31″ x 41″]

There’s a period that I never shook off from childhood, that of collecting. As a kid I collected rocks and minerals and fossils, and later graduated to beer cans, so I went from natural history to cultural production. I was only interested in the beer cans that I could find on my own because then there was a story attached to them. That informs how I make collages too. My process involves physical space; it involves going out into the world and finding books. I never buy anything online, I find them in person because I have to know what the paper feels like and assess the quality of the images.

There’s this myth of control: if you’ve got a bunch of things, your life’s in order. Which it isn’t necessarily — it just means your collections are in order.

The maximalism comes out of wanting to see everything all at once, like an overview, and imagining that I could manage that or control it. There’s this myth of control: if you’ve got a bunch of things, your life’s in order. Which it isn’t necessarily — it just means your collections are in order.

H: But there’s also something visual going on in the mass. There are ethical and formal concerns that are both at work.

MO: I’m always looking for the variable in the large dataset. I’m tuned into lots of things and what makes one different from the next. I think you can only get that by assembling a large number.

H: A kind of Warholian repetition?

MO: Warhol was inspired by manufacturing and production, but valued the aberration; seeing himself as one, he couldn’t not. And he carried that into the work. It’s process-oriented but about breakdown and dissonance; even though it’s the same thing over and over again, it’s really not. It’s what they do together that makes it transcend itself.

[Andy Warhol, Shadows, 1978-9, 102 silkscreen panels; Dia Art Foundation, NYC]

H: Do you think if you got them ALL, it would finally mean something?

MO: It stops at some point, but it is easy for me to think of all of my pieces as a single evolving work. I suppose in the end it’s an aesthetic too. I never had a minimal approach to anything.

H: You deal with the imagery of sending messages to the future from the past. Those futures did not actually occur, which gives the imagery, and the messaging, an interesting parallax.

MO: All fiction claims the possibility of things actually going this way, or saying something like this has happened somewhere. I think in the visual arts we have a broader, or more slippery, set of potential outcomes. You can be focused almost to the point where there’s only one reading for an artwork that everyone “gets.” That’s a kind of universality which I find uninteresting. Then there’s the work that invites many simultaneous readings and directions. It may still be highly scripted… but everything from there is more interesting by degrees.

[Michael Oatman, All Utopias Fell, 2010; Installation, MassMOCA, North Adams, MA; photo by Andrew Sempere]

Once I was fixing something in an installation in the lobby at MassMOCA. It was a teaser campaign before the ship landed (All Utopias Fell). I had these control panels that were communicating with the closed-circuit TV system in the museum, and I had written a wall text called The Mystery of Building 5, next to an explanation about solar panels. I created this other layer, introducing a character, “Donald Carusi,” an employee at Sprague Electric, and displaying some of his tools, not really explaining what they did but saying that they were discovered by the museum workers.

Nobody stands in front of a Mark Rothko painting and says, ‘this isn’t true.’

So this guy comes puffing over from the Information Desk because they had pointed out that the artist was over there and he says, “did you make this?” And I said, “yes,” and he’s like, “this is unacceptable! You’re lying to the public, I read this The Mystery of Building 5, none of this happened, this is incredibly misleading!”

He was really in my face, and I said, “you know, nobody stands in front of a Mark Rothko painting and says, ‘this isn’t true.’ ”

[Truth or Dare: Woman in front of Mark Rothko’s White Centre (Yellow, Pink and Lavender on Rose), 1950]

And he’s like, “what do you mean?” and I said, “well, you know, if you buy a novel and you’re reading it, don’t you hope to get into it at some point, don’t you hope to be transported somewhere, don’t you hope that the writer takes you on a trip?” And he’s like, “yeah…,” and I said, “well, I’m not a writer, I use these materials and I make these propositions and this text is part of the still life. I can’t write novels but I can do this; this is how I make worlds, right?” And he’s like, “oh; ok.”

He got it, and he went away — not exactly happy, but at least he was not intent on injuring me anymore.

[Michael Oatman, The Peaceable Kingdom (Nutrition Error), 2008, Book cuttings on paper, 12″ x 16″ (paper size 18″ x 22″)]

H: The juxtaposition in your images owes a debt to Surrealism, but much of your work has a strong moral message, especially about the environment, and technology.

MO: It’s much easier to be moral in a picture than in your own life; maybe that’s one reason it’s so appealing. My pictures have better ethics than they do morals. I think of morality as personal and ethics as cultural; there are broader social themes in my work. The personal is in there, but it’s more embedded.

I’m always interested in the big picture, and that’s why the collages are, generally, big pictures — a literal manifestation. I’m operating in the realm of history painting, but chronicling not so much scientific inquiry and historical events, as the aftermath. And the set-up for the next thing. I think paradigm shifts always challenge people’s morality and basic beliefs.

[Michael Oatman, Rural Beautification (Dutch Masters), 2007, Book cuttings on paper, 10″ x 13″]

The content of the work is also borne out of where I grew up in Vermont. I’ve always been interested in how the things that we tried to do as kids that were about control inevitably always failed: like damming up a little stream, and the water always washes that away. Or getting lost in the woods. There is something so much bigger than yourself that is at work; the natural world is a great teacher about how things are interdependent. That was a great point of entry as an image-maker.

I could use stuff from the real world to make a powerful statement about what we were doing to it or how we found ourselves in it.

As I was making imagery out of found books I was also starting to gather objects and enter the realm of installations. I began to think of the way in which I could use stuff from the real world to make a powerful statement about what we were doing to it or how we found ourselves in it. Installation was a way of merging the movement from film, the intentionality from painting, and the exposition of a subject from writing.

The most powerful of positions to take as a maker — putting images into people’s heads based on your words.

As a young person who read a lot, the worlds that writers were conjuring up were really powerful because I was responsible for inventing the images. That seemed to me like the most powerful of positions to take as a maker — putting images into people’s heads based on your words.

[Michael Oatman, All Utopias Fell, 2010; Installation detail; photo by Peggy Nelson]

H: A lot of your work has embedded text. Sometimes it’s just single words but often it’s poems, books, even entire libraries. It’s obviously not just another visual element.

MO: I try to make it visual. In the spaceship there are titles in the stained glass window; there’s writing on the ceiling; there’s a Richard Brautigan story on a labelmaker strip called I was trying to describe you to someone. The most overt text-based component of that installation is The Library of the Sun; there are books in there about nuclear power and energy and what fuels stars, there’s astronomy, and there are books about communes. In the video I’m holding up another series of labelmaker strips which are the character’s last communication. And then there’s the absent text of the wallpaper diagrams, which were taken from a physics book.

[I was trying to describe your installation to someone; All Utopias Fell, Installation detail; photo by Peggy Nelson]

H: And the absent text of the character himself?

MO: Maybe that’s the biggest one. The virtual text is my own writing, but those acts of using words are almost always somebody else’s words. I think for me it’s another way to acknowledge that writers have been important to my identity as a visual artist.

[Michael Oatman, All Utopias Fell, 2010; Installation detail; photo by Andrew Sempere]

I always feel like I’m substituting things. I’m not making movies, I’m making these physical stand-ins for movies. I’m not writing novels, I’m writing characters into existence using objects. When I was making paintings I never felt like I was painting them, I felt like I was building them. There’s always an avoidance of doing the thing that I’m supposed to do.

Especially when you transgress, that is a lot more like how I want you to operate in my spaces.

We don’t go into our friends’ homes or into restaurants or shopping malls and consciously read them, but that is what’s happening. There are cues that remind us that it’s safe or familiar; or that it’s exciting because we’re not supposed to look into the medicine chest. Especially when you transgress, that is a lot more like how I want you to operate in my spaces.

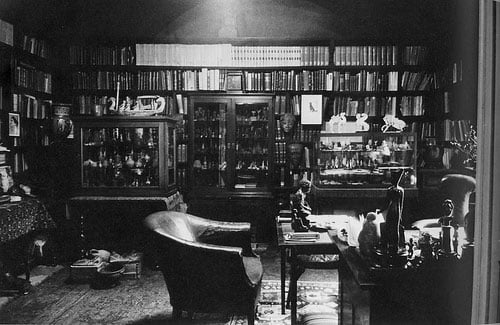

[Edward Engelman, Freud’s Consulting Room, 1938]

H: When I was in the airstream, I was reminded of the pictures I’ve seen of Freud’s consulting room, which was encrusted with fabrics and statues and pictures and Victorian bric-a-brac; a very dense psychological space manifested in the materials. All Utopias Fell felt like that to me. Would you say that an installation like that is some kind of surfacing of unconscious elements? Is it a self-portrait?

MO: I think they’re all self-portraits. But that wasn’t obvious to me when I started doing this.

H: It was not?

MO: No. But then I did this project about eugenics, Long Shadows: Henry Perkins and the Eugenics Survey in Vermont, 1995/2000, where I was presenting the ideas of this 40ish University of Vermont professor, Henry Perkins, who was trying to pass legislation to sterilize people in the early 20th century.

If you’re going to create a world or if you’re going to remake a world, you’ve got to own up to it, and you’ve got see how you’re implicated in it.

What would have been easy would have been to say that Henry Perkins was a monster. But he wasn’t. He was definitely a product of his time and felt that he was motivated by the best reasons. Now we would call him a racist and a misogynist and a classist. And yet he was a born-and-bred Vermonter — like me; and he was a college professor — like me; and he was a white guy — like me.

[Michael Oatman, Long Shadows: Vermont Pure, 2000; Installation view, MASS MoCA, North Adams, MA]

I had to see myself in that, or else go home and give up making this kind of work. Because if you’re going to create a world or if you’re going to remake a world, you’ve got to own up to it, and you’ve got see how you’re implicated in it.

[John Hampson, Portrait of George Washington, late 19th century, Collage of insect parts; Fairbanks Museum and Planetarium, St. Johnsbury, VT]

Long Shadows was in some ways about conflicting parts in me that were inspired by museums when I was a child, but then realizing, after doing some critical reading, that museums are one of the many manifestations of colonialism. It wasn’t that they were inherently bad; it was that they were inherently problematic.

It wasn’t about needing to find a hook, like a pop songwriter; it was sensing that the most powerful stories were the ones that you had to work really hard to acknowledge.

I came of age in the moment of identity politics, and as a white guy being confronted with all these stories that were sort of “against” me, I needed to find some way into that to have a voice. I chose criminality, or aberrant behavior, or my family’s own tough history with mental illness. It wasn’t about needing to find a hook, like a pop songwriter; it was sensing that the most powerful stories were the ones that you had to work really hard to acknowledge.

I gravitated towards institutional formats, things like archives and libraries and places where a lot of human information had been databased.

[Michael Oatman, Conservatory, 2005; Glass negative detail]

For example, finding 18,000 glass negatives [of Albany County, NY inmates, source material for Conservatory] was a way to examine how people had been compartmentalized and managed by a database.

This was likely the only portrait of them that would ever exist, and they would be known forever as criminals.

Those photos were taken at a time when most people had never had their photograph taken. This was likely the only portrait of them that would ever exist, and they would be known forever as criminals.

[Michael Oatman, Conservatory, 2005, Installation. Conservatory is an 18’ long, 12’ wide, 10’ high greenhouse comprised of steel, Plexiglas and 2500 glass negatives depicting Albany County inmates, ca. 1898-1923. It also includes plants grown in the wooden crates that housed the negatives, gardener’s tools, special lighting and features an audio soundtrack by harmonica virtuoso Douglas Johnson.]

The recognition that one could appropriate institutional forms and then make them personal, make them self-portraits, insert my own narrative into them, is what I think finally made my work. I wasn’t being overt in where I was in the piece, but it was informing almost every decision.

H: So why things? Why work with objects in the digital age?

MO: When I was in graduate school, I continued painting on canvas for awhile. But then I started finding these box-spring mattresses on the streets of Troy, like, all the time. We have a lot of retirement homes here, and I just assumed that somebody died and they took their bed out. Beds are the most storied things that we have. It wasn’t like taking a piece of paper and writing on it, it wasn’t a blank canvas; it had supported a body and supported a life story. There was no imagery yet, that was my job, but I felt like I was channeling the stories somehow in using them.

I think I began to see every object that way. I’m not so interested in new things.

H: You have an iPad.

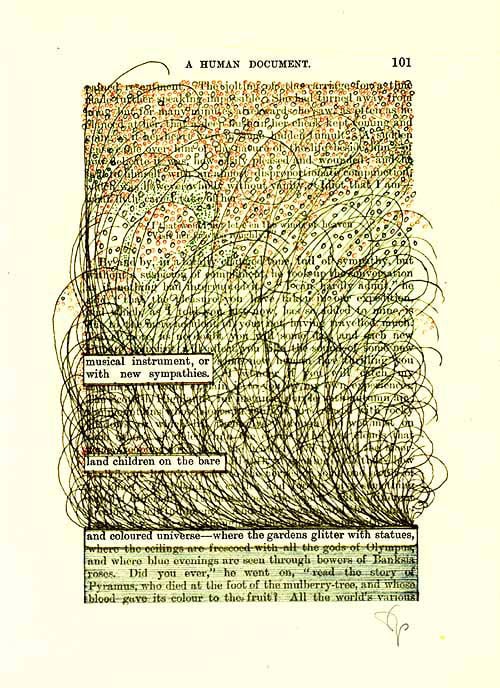

MO: Yeah, I do have an iPad, right, which by the way has the app for A Humument on it. It’s a one-to-one scale, a great way to see that book.

[Tom Phillips, A Humument, A Treated Victorian Novel, 1970-ongoing, altered book, a piece of art created over W. H. Mallock’s 1892 novel A Human Document; page detail]

I decided that for my artwork, I wanted to start with things that had a story already. But it wasn’t my interest to stay in that moment. I wanted to make a link between that moment, meaning the object’s origins, or the past; what I was doing to it, meaning the present; and what I was saying about it, which meant the future.

I take seriously the mission or the role of the artist as somebody who sends messages out into the future.

I take seriously the mission or the role of the artist as somebody who sends messages out into the future. Sometimes the things I make now have meaning for people, sometimes they don’t, and sometimes I think they don’t have meaning yet.

[The Allen Telescope Array]

If the world were to end tomorrow, I don’t think I would continue to make art.

Which is why I like thinking about the particular part of NASA’s space program that has been about patient, epic, long-term attempts at communicating. I think the SETI Project is one of the most beautiful ideas that humans have produced.

If the world were to end tomorrow, I don’t think I would continue to make art.

H: You wouldn’t be here! What do you mean if the world ended?

MO: I mean if I was the last person on earth. I probably wouldn’t make art anymore.

H: What would you do?

MO: Well I would…

H: …walk around?

MO: I’d probably go and gather books that I like and…but I think art for me is essentially about a kind of communication.

H: And a future?

MO: And a future, right. There is the problem of how important is it to be understood. I’ve decided it’s not as important to be understood as it is to prompt a set of emotions and to pique an interest level. I feel like a lot of us have this stance as artists because it’s how we like experiencing the world ourselves.

That’s one of the great things of the internet — epic simultaneity of experience. Or at least of the information that can lead to an experience.

When I find something, my impulse is to present it to somebody and say, check this out, it’s amazing. That’s one of the great things of the internet — epic simultaneity of experience. Or at least of the information that can lead to an experience.

All of these projects either suffer or succeed based on how far in my audiences are willing to go. Some people can spend hours with a piece; some take 30 seconds and decide it’s not for them. I’m not interested in solving the universality concept.

H: I don’t think it’s solvable anyway.

MO: What I like doing — and this comes directly out of computing even though I would not call myself a new media artist — is designing levels. I build stuff below the 3-foot mark so that people in wheelchairs or children can have a slightly different experience. I see my work as something you can “play” on expert, beginner, or somewhere in-between.

[Michael Oatman, All Utopias Fell, 2010; Installation detail; photo by Peggy Nelson]

I’ve got this meta theory about the idea of covers, like when a band covers a song.

H: I heart covers.

MO: What?

H: I heart covers!

MO: …is that a band?

H: This is an emoticon. (making heart with hands) HEART!

[Merton, Chatroulette Piano Improv #1, 2010; excerpt]

MO: …right. So anyway, the idea is that when Super 400, a power trio from Troy, covers Whole Lotta Love by Led Zeppelin, it’s not a parody. They’re interpreting it, not ridiculing it.

H: But if you painted a soup can, forget it!

MO: We can’t do it in the visual world. It’s the one limitation, the one thing that I’ve come up with that makes a break with all the other arts. So, what does it mean when I use an airstream trailer to make my piece? Because there’s always going to be that part of the crowd that’s more into it as an airstream than what I transformed it into. They see it as a kind of parody, or…

H: So it’s ironic or it’s nostalgic.

MO: Yeah. Where nostalgia or irony might not come in to somebody covering a song, it’s always present in visually appropriating something that’s iconic.

[Michael Oatman, Blanket, 2002, Collage and spray paint on paper, 100″ x 100″]

I was really confronted with an inherent problem in my collage work about 5 years ago when I went to FedEx to mail a package, and their holiday ad campaign was FedEx jets in snowflake formation, falling. I retained an intellectual property lawyer, and we put together a package. My piece had been reproduced in magazine articles, and the people who pay a lot of attention to the art world for inspiration are the graphic designers. I all but got one of the graphic design people at their creative agency to admit to the fact that he appropriated my image, but he wouldn’t do it for the record.

So I sent the letter and FedEx wrote back and said: “Hey, have at it. We’ve got 70 billion dollars and 300 lawyers and you don’t own this idea.” I got that letter and I realized — I was going to sue FedEx over them taking my imagery, when I’ve been taking the illustrations of dead illustrators for years! And… I realized they were totally right. I hate to say that about this giant company.

H: /laughing

MO: It was a great lesson. Now when I show Blanket I sometimes show their poster with it.

If you’re an artist that appropriates things, and you’re going to play that game, then you should be prepared and honored for it to happen to you. And I was, in the end.

H: Right, your own medicine. You took it.

If you’re an artist that appropriates things, and you’re going to play that game, then you should be prepared and honored for it to happen to you. And I was, in the end.

All Utopias Fell may be visited at MassMOCA in North Adams, MA, from May to October, until 2020.

Michael Oatman is represented by the following galleries:

MillerBlock Gallery, Boston, MA

Lenore Gray Gallery, Providence, RI

Stremmel Gallery, Reno, NV

Initial quote from Aldous Huxley, Brave New World, 1932; Chapter 8

Joshua Glenn’s Generational Periodization Scheme