Watching the Detectives

By:

September 4, 2011

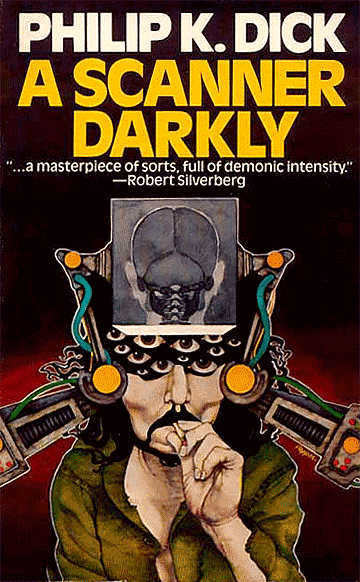

Who is Richard Linklater, really? In the last 15 years he’s written and directed great, meandering films about disaffected types who don’t do a whole lot of anything besides kicking back and philosophizing (Slacker, Dazed and Confused, Waking Life), but he’s also made tightly plotted movies about equally disaffected types who band together to combat a repressive social order (The Newton Boys, Fast Food Nation, even The School of Rock, and Bad News Bears). It’s as though the left and right hemispheres of Linklater’s brain have been competing! Which is, of course, precisely the problem faced by narcotics agent Bob Arctor, the protagonist of Philip K. Dick’s brilliant 1977 science-fiction novel A Scanner Darkly.

[This essay was published by Slate on June 27, 2006 — shortly before Richard Linklater’s adaptation of Philip K. Dick’s A Scanner Darkly premiered.]

So, will Linklater’s new, rotoscoped adaptation of A Scanner Darkly, starring Keanu Reeves as Arctor, reveal once and for all which side of Linklater’s brain is the dominant one? That is, will Keanu and his drug buddies, played by Robert Downey Jr., Woody Harrelson, Winona Ryder, and Rory Cochrane (reprising his role in Dazed and Confused), get politicized and take action against their not-too-distant-future surveillance society? Or will these slackers stay glued to their couches, entertaining themselves with interminable Linklater-esque bull sessions?

The answer is: both. After all, in what sf fans describe as the “phildickian” worldview, binary opposites — good/evil, real/unreal — are impossible ever to untangle. That’s why Arctor has such a tough time deciding whether he’s a narc posing as a doper or vice versa… and that’s before he’s directed by his narc superiors to set up surveillance on a suspicious doper: himself. In Linklater’s Scanner, that is to say, audiences may finally catch a glimpse — even if through a glass darkly — of the director’s own paradoxical worldview, one in which slacking is not only a form of political activism but the only possible activism.

In order to get a firmer grasp on this chuckle-inducing notion, it’s necessary to revisit the intellectual climate of the mid-1970s, when a middle-aged Dick was playing host to gun-toting drug dealers and their teenage clients, downing gruesome quantities of speed, and working fitfully on Scanner. In those years, socialism as a doctrine and a movement no longer seemed capable of arresting the progress of the insurgent political, economic, and cultural doctrine that during the market-worshiping 1980s would come to be called neoliberalism. Disappointed soixante-huitards everywhere sank into their couches and succumbed to irony and lifestyle radicalism. In France, however (where Dick’s fiction was treated with the kind of respect formerly accorded only to Poe), thinkers like Michel Foucault, Gilles Deleuze, and Félix Guattari offered up theories of how social control was now exercised not through class domination but increasingly subtle mechanisms.

In 1972, for example, Deleuze and Guattari claimed in Anti-Oedipus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia that Westerners have been “oedipalized” (normalized, trained to desire their own repression) at home, at school, and at work. In ’75, Foucault’s Discipline and Punish concluded that the modern liberal state was a neototalitarian apparatus designed solely to optimize the economic utility of recalcitrant individuals. Giving up on the workingman, radical intellectuals cast about in unlikely places for a new revolutionary subject. Deleuze and Guattari praised the psychotic as someone incapable of being normalized and suggested that people be “schizophrenized.” In Italy, Antonio (Empire) Negri located the agent of social revolution among those marginalized from economic and political life: the criminal, the part-time worker, the unemployed. And, in a 1977 interview, Foucault said he was looking for “someone who, wherever he finds himself, will pose the question as to whether revolution is worth the trouble, and if so which revolution and what trouble.” Lazy, shiftless, half-crazed revolutionaries? Call them: slackers.

By then, Dick had been writing for more than a decade about semi-employed, drug-using, near-schizophrenic schlemiels who through sheer stubbornness and perversity succeeded in their struggle against neototalitarianism and irreality where heroic types had failed. Forget, if you can, that previous Hollywood adaptations of Dick novels have starred the likes of Harrison Ford, Arnold Schwarzenegger, and Tom Cruise: “I know only one thing about my novels,” Dick wrote in a 1970 letter addressing himself to critics who didn’t like his unglamorous, anti-heroic protagonists. “In them again and again, this minor man asserts himself in all his hasty, sweaty strength.” And in a 1972 speech, Dick stole a march on Foucault, et al., by praising the “laziness, short attention span, perversity, [and] criminal tendencies” of the lazy, shiftless, half-crazed American slacker. (“We can tell and tell him what to do, but when the time comes for him to perform, all the subliminal instruction, all the ideological briefing, all the tranquilizing drugs, all the psychotherapy are a waste,” insisted Dick. “He just plain will not jump when the whip is cracked.”)

It’s tricky to portray the slacker’s qualities as progressive ones, as Dick was all too aware. And here in our own repoliticized era, when even a Hollywood broadsheet like Variety complains that Linklater’s Scanner “misses the boat by not linking its themes more explicitly to the political realities of the present, particularly when issues of unlawful surveillance have rarely been more relevant,” convincing American audiences of the virtues of what we might call slacktivism — if we could rid the term of its pejorative connotations — appears impossible. But this is what Linklater has tried to do from the start. For would-be slackers who need pointers on dodging the exploitation of labor, he’s directed The Newton Boys, the real-life story of a band of brothers who robbed banks in the 1920s, and The School of Rock, in which Jack Black never once ceases to scheme for ways to avoid holding down a job. And for those of us already convinced of the merits of unwork, he’s made Slacker, in which Austin, Texas, is portrayed as a noncoercive utopia dedicated to jawboning; Waking Life, a walkabout in which Wiley Wiggins (Dazed and Confused) gets rotoscoped and enlightened; and other films.

Keanu Reeves may not be a particularly talented actor, but if anyone could make the figure of the slacktivist — part couch potato, part action hero — a compelling and sympathetic one, the star of Bill & Ted’s Excellent Adventure and The Matrix is doubtlessly the proper choice. All of which is not to predict that Scanner is going to be Linklater’s best film yet, but it might be his most revealing one.

READ MORE essays by Joshua Glenn, originally published in: THE BAFFLER | BOSTON GLOBE IDEAS | BRAINIAC | CABINET | FEED | HERMENAUT | HILOBROW | HILOBROW: GENERATIONS | HILOBROW: RADIUM AGE SCIENCE FICTION | HILOBROW: SHOCKING BLOCKING | THE IDLER | IO9 | N+1 | NEW YORK TIMES BOOK REVIEW | SEMIONAUT | SLATE

Joshua Glenn’s books include UNBORED: THE ESSENTIAL FIELD GUIDE TO SERIOUS FUN (with Elizabeth Foy Larsen); and SIGNIFICANT OBJECTS: 100 EXTRAORDINARY STORIES ABOUT ORDINARY THINGS (with Rob Walker).