Linda (10)

By:

August 4, 2011

HILOBROW is proud to present the tenth installment of Karinne Keithley Syers’s novella and song cycle LINDA, a hollow-earth retirement adventure with illustrations by Rascal Jace Smith. Linda is taking a summer holiday and will resume her weekly Thursday appearances on August 25th.

The story so far: In last week’s installment, our retired math teacher heroine Linda was led to a large underground lake where a squadron of squid performed a dream ballet instructional showing Linda the possible impending collision of a comet with earth, and her role in its approach.

20.

Conatus Lindavatus

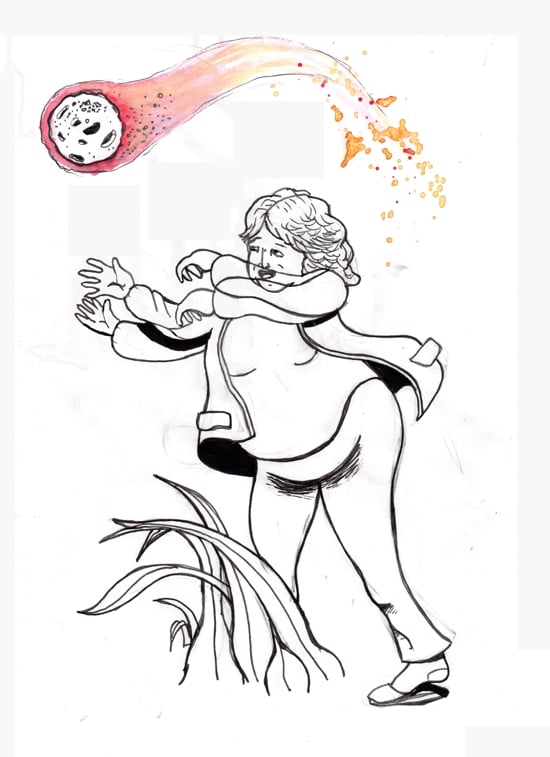

Dream ballet as tutorial in comet calling teaches Linda to issue invitation by something between a holler and a song. If we had continued to watch her, we would have seen too that she learned in that squid scene how to stop the comet, to direct it to join the quiver until, vibrating at a higher and higher pitch, it turned to dust then to sound then to nothing. So she learns of her power to both call forth and reject terrible things. Left to consider the use of calling forth the comet, she finds there is no logical answer, and so sets the idea of it adrift in the oceans of her own imagination, commits herself too to the waves, to follow its float until she finds her answer. Such spectacle must require a response. So when Linda leaves the boat and returns to the small beach, she leaves Bessad and the others and even dog-Linda behind, requesting instead the opportunity to walk alone and think, and makes her way back up the tunnel with its veins of light, until she reaches the entry way, and sits down on the round bench to think.

Linda finds again the report of Professor Byrd Friend, this time reading further into the narrative until it turns to speculative natural history of a squid-tree kingdom. Reads through chains of description of vein branching and light turning reaching finally a section on the breeding of the effort to thrive, the will to survive, philosophical name Conatus.

From the room’s many branching tunnels she finds one that leads to a new chamber, where she discovers a ladder placed just under what she guesses is the large trunk of the smoke tree in the clearing. The trunk has been hollowed by hand, and though dug-out it is not dead. Veins running an opaque liquid feed into the tree’s sides like intravenous lines. Linda puts her hand to the wood to sense its health, finds it intent or intense, facing up and out and beyond. She climbs up the ladder and reaches a kind of room, fitted with a small perch and a leaded window laid into the space where a knot in the trunk once was.

I do not think there is to be a heroic aversion, even though I have built for Linda a globe and given her a vision, even though I have said she will walk out into the globe and deliver us from peril I realize I do not think she will, though of course I cannot know. I wanted to write Linda a retirement adventure, a cross-country pleasure trip, an American senior citizen liberation festival, to give her the wild happy surprise that belonged to whatever she envisioned when she told me, “I feel like I just graduated from high school, like I could do anything,” which she did tell me, in Knoxville two years ago when I met her in the hostel. And then I wanted her to discover some great and dangerous second world in the forest and below the hills of this same country, and for Linda, gut problems and all, to be hero, to be savior, the leader of a ragged insurgency forging a new survival in a demolished world, to show Al and everyone else what she could do, to discover a country in retirement and to solve it.

But lately I have come to wonder if some things are too much. In Indiana last summer I went to a counter place, the kind where a meal of eggs and toast costs less than $2. In Indiana you can still smoke indoors, and so people in there were smoking, in this tiny place. Next to me was my husband, whom I had just married not two weeks before, and we both sat astonished and amazed, loving this man at the end of the counter, who sat smoking and drinking coffee and talking loudly to the woman proprietor and the people on the other side of us, a grandma getting a shoulder rub from her 13 year-old grandson, and I remember nothing of what the man said, only how we thought he must be the most beautiful human we had seen, and his face, which was so leathery and yet so full and soft he was like, I realize now, a kind of lion. In some ways I guess he was a kind of destroyed human, and maybe it was that that made him so unearthly beautiful, or maybe it was the fullness under all the destruction, the wiry dryness of him like a living apple doll. I wonder if I can call him Leon, but I think I shouldn’t, because as I write this I’m pregnant with a child we would maybe like to call Leon, or Leo for a girl. So I’ll call him George, George the lion of New Albany, Indiana.

L is for Leon but also for Lawrence, which is the name my grandfather chose, Larry, although his given name was Frances; he was F.R. Keithley, for Frances Ray. New Albany, Indiana, George’s town, is the town where my grandfather was born. Being from the coasts of this country it was a shock when my father, researching our family genealogy, discovered the family had been in Indiana for five generations before my grandfather left, moving in some order to Battle Creek, Denver, and Chicago and eventually to California, India, Japan, Thailand, and again California, where I was born. My own childhood was split between California and Northern England, and then I moved to New York City, and so Indiana was a shock of a self-concept and we had driven there to sound it out, to find some sense of recollection beyond the knowledge of facts. In New Albany, just after we left George still smoking in the diner we found the graveyard on the edge of town, and found the graves of many Keithleys, although not the grave of the one who was kidnapped by Indians (was she Sarah?), and not the grave of Nola, who divorced her no-good husband, a drunk, and whose name I like so much. There is a picture of me squatting by two small graves, smiling and buxom like a new wife. Those graves so small must have been children’s graves, must have borne the carved emblem of a lamb, the customary marker of childhood death in the artifacts of passed Protestants.

I remember what I meant to say: there was a scientist, an anthropologist, who described the experience of working in a cave painted with lions, and at the end of five days couldn’t go back in, the experience was so intense, and I thought too of the caves in Forster’s Passage To India, and I began to experience a kind of remorse for sending Linda underground and into this globe that will not reveal its function, that would smell just a little of sickness if you had been there long enough to forget the wonder of squid or appearing refrigerators or sourceless light making color washes as if the world of three dimensions only extended locally and came to a peaceful end just around the corner in a flat wall of pattern like the old hunting book of Gaston Phoebus. I felt I was maybe wrong to sending her where the only offerings are made in caves. Though the anthropologist who found the caves so intense had come to them intentionally and at the end of what I can only assume was a painstaking demonstration of preparation and credential, it is almost as if this man was discovering the caves accidentally, buttressed not at all by foreknowledge, like the wandering group of kids who in 1940 entered the Lascaux caves and discovered its bestiary around them. The awe of it reduces our self-possession the way the high pitch of the clarinet made my brother crumple when he played it, and like the panic I felt in my recurring dreams in which aliens without faces invaded our village and walked through it in procession playing a single melody on clarinets with no keys. When I woke up in the middle of the night in terror, I would calm myself down by visualizing a pond with three ducks in it, a technique whose origins I no longer remember. When I was younger still I had what are called night terrors. I would get out of bed and run screaming through the house and sometimes throw up though still asleep, remembering nothing the next day when my exhausted mother asked me if I knew what had happened in the night. No, I would say, and turn my head to see if the peacock that visited our fence from the farm across the street had come. Some things are too much.

So Linda won’t stop the comet, doesn’t choose to be the hero. She peacefully awaits it, calls on the quaking and the raining, the flooding, the darkening. She sits, above the long tunnels to the room with the circle bench just below the surface, above the ladder leading into a kind of tower hollowed into the space of the tree, cut with windows veined with thin lead nestled into the opening made by an old knot, an opening in the tree giving way to an opening cut in the canopy, allowing her a clear sight up, into the atmosphere, the stratosphere, into space.

Throwing her voice clear and far, visualizing its unhurried arrival at its distant object, the way she learned to bowl, she begins to sing. Linda discovers a sense of will in the singing. What will I be to all of this, asks Linda, because I do feel that I could do anything at all.

Far off, something receives a call.

21.

Carved into the wood walls of the tree are orbital models, with tracks hooked through each other and many more than nine planets: an endlessly interlocking series of solar and parasolar systems only visible from the globe. When at night she looks up at the sky, Linda allows herself to place this map of all these planets up there, a kind of transparent overlay, concentrates until she can see them, enjoy them, until their figures boomerang back, etch into her retina. She gives each new planet a name, names of old students. There’s Henry and Henry minor, Alice, Ray, Ada, Brian, Matthew, Josh. The more she looks, the more apparent they are. She sees the sky now as a puzzle bracelet pulled apart, a series of glinting points along so many interlocking loops, and she mentally replaces the kinked loops into each other, imagines them reassembled, a perfect circle of light.

Linda leaves her perch with her eyes still full of this light and descends the ladder to the hand-dug hollow, which gives onto the tunnel that leads to the lake as well as other tunnels Linda hasn’t explored. When she climbs back down the stairs and sees the circular bench around the low globe of light, this circling light aligns with the one still hovering in her eye, producing a violent combination. She temporarily cannot see anything but light. Her throat parches and she panics, cries out, and hits the ground. From somewhere dog-Linda comes running to her, licking her face until she reorients herself, pulling up to the bench and willing the light out of her eyes.

Up the corridor behind the curtain, someone shuffles forward. Al emerges into the room, looking shocked and undone. “Linda,” he says, and she says back, “Al.” They stare at each other, Linda unsure if she is glad or annoyed at Al’s presence. Al is only more distressed, unable to decide if Linda’s appearance here causes comfort or more fear. Sweat stains the collar of his shirt yellow and drenches his pits. Linda becomes conscious of the inside of her nose, feels that her whole being is just a field of intelligently waving hairs working to determine the precise value of the smell coming from Al’s pores.

“I guess you want your van back,” she says, and Al begins to weep.

Bessad now appears accompanied by a woman, who Linda thinks might have been on the beach below. Usually such a formal lady would intimidate Linda but the sense of her own power has grown significantly since standing on the squid and calling to the comet, and its momentary lapse has been forgotten. She greets this immaculate lady with the deeply unimpressed and perfected once-over of a townie. Bessad suggests they speak in the other room. They are expectant. Linda feels like she just graduated from high school, like she’s free and powerful. Neither Bessad nor the woman speak. Linda takes Al by the elbow, bringing him in, depositing him on the couch. The woman reaches into her pocket and brings out a small device, hands it to Al, who stares at it. In the green glow of its screen, Al looks unhealthy. He looks sick. He coughs, hacks something up. It glows. It’s an eggshell, I think. He coughs again and brings up an acorn. Again, and up comes half-chewed cheese. This bewilders and embarrasses him. Dog-Linda comes over and eats it off the floor, then licks his hand.

The woman gestures to Bessad, who turns to Linda.

“She wants to know when it will come.”

“Now,” says Linda. “It’s here.”

The sound, at first, is like a military jet on a practice drill in the sky above your small house as you sit at the dinner table eating bread and salad, the two items after beer that my father has named necessary in this world. The fast streak of broken air shatters the water in the lettuce, rings in your teeth and in your jaw below your ear. Wax begins to accumulate. For a few minutes there is only this sound, and then a kind of tumbling, like the sound of a boulder coming down a creek in a flood, and then the horns go off, the horns of every small town ringing the forest, towns just beyond the boundaries of the globe, calling volunteer firefighters out and ordering everyone else to their basements. Dog-Linda moves to the door and sets up a howl, but whether it’s answered or not is impossible to say, the rumbling now so loud that no other frequencies emerge from it. Al has curled up into a ball on the couch. The woman stands with her eyes closed, Bessad stares at the floor by the couch where the acorn and the eggshell are vibrating, and Linda, giddy, lies down on her back in the middle of the room, limbs extended into a big X, welcoming the tremors passing from the floor to her body, laughing a little as her fluids shake. It sounds now the way it might sound if you were locked in a practice room with a hundred drummers all hitting cymbals: it is blood-riling and earwax-inducing and it is increasing. Then the sound stops, and all that can be heard is a diminishing thrum in the blood, and then the sound of the heart, and then the sound of dog-Linda licking Linda’s hand, and then just the sound of your breath as you read this.

Linda will leave the room and walk out into the globe, and it will be covered in a fine silver dust. Nothing in the immediate area will have changed but for this slight silvering. She will walk past the Smoke Tree and stop at the the clear-running spring and see that it is running a virulent burgundy grey now. She will go through the grove with no underbrush and the vined-over mountain range and the Catalpa and the Custard Apple. She will cross the stream, moving to the edge of the forest, where she will climb a tall, bare hill that gives her a view of the globe, and she will see with pleasure a further off, taller, and even more bare hill that has been transformed volcanic by the intrusion of the comet, the comet she called, which has plunged clear down into the earth causing the displaced earth to spume upwards, refined by heat, into the air where it catches a set of currents blowing radiantly outwards and over the edge of the globe where it gathers intensity and rains down with force. When she returns down the hill and reaches the edge of the globe, she will see nothing but dust, flattened towns and dust. Whole developments rubbled. Billboards on the side of the road advertise nothing but the color grey as if selling the absence of thought. She will not stop at the edge, will feel no awe or trepidation. She will keep going, walking out into the dust, and all the time smiling privately and very low and lasting in her body, like she could do anything she wants, like she’s free.

END OF PART TWO

And now, listen to the the comet yodeling on it’s way to you (NB its full spectrum bass yodel only available with headphones or accommodating speakers):

UP NEXT: A little summer vacation. When Linda returns to start part three, on August 25th, she finally gets to redeem her senior discount. Stay tuned!

Karinne and HiLobrow thank this project’s Kickstarter backers.

READ our previous serialized novel, James Parker’s The Ballad of Cocky The Fox.

READ MORE original fiction published by HiLobrow.