Copybot

By:

July 27, 2011

[Hallstatt copied in its reflection, Austria]

Recently it was reported by Der Spiegel that an area in the city of Huizhou, China (about 100 miles north of Hong Kong), perhaps cognizant of its location on suitably angled hillsides, had decided to update its look. It is making itself over into an exact replica of a European village, but not just any village — it will be a replica of Hallstatt, an Austrian UNESCO site.

Despite this being a copy of the thing, in bricks and mortar no less, what is copied when a thing is copied is not the thing. Even if it is a thing, a material thing, an inhabitable thing, a thing containing gardens in which the reenactor playing Bishop Berkeley could walk with Samuel Johnson, a garden containing rocks which the reenactor playing Samuel Johnson could kick with his material toe — even if it is all this and more, what is copied when a thing is copied is not the thing, it’s the idea.

[The idea of happiness, Thames Town, China]

The power of the idea is such that, in order to copy a thing, you don’t even need the original to be a thing in order to copy it. Witness towns like Florida’s Celebration, where potential inhabitants were wooed by, not a copy of a real place, present or past, but the idea of a perfect postwar small town, as art-directed by Disney. Or perhaps The Village at Hiddenbrooke in Northern California (near Vallejo), built as a 3D version of a Thomas Kinkade, Painter of Light™ English-style country village scene, or rather a sentimentalized ideal of an English-style country village scene as depicted on a Thomas Kinkade, Painter of Light™ poster in the gift shop at the mall.

[Director’s notes, Celebration, Florida]

[Candlelight Cottage by Thomas Kinkade, Painter of Light™]

Disney (via its subsidiary development company, “Celebration”) had also planned to create a copy of a picturesque northern New England ski town, in Bretton Woods, NH, which is itself… a picturesque northern New England ski town. Before you can process the recursive wonder of that, you should know that the deal fell through. For now.

[The Mt. Washington Resort, Bretton Woods, New Hampshire]

And what about reconstructions, ranging from “real” ones like Colonial Williamsburg to invented ones like Massachusetts’ Old Sturbridge Village? They’re both representations of our idea of history, one placed atop the real, the other placed, “nearby” — but they are both ideas, as is any architecture at a remove from its initial construction. Which is to say, all architecture, at all times.

[Thruce Hammer reenacts walking away, Old Sturbridge Village, Massachusetts; photograph by Bill Greene]

The copy of the UNESCO village is not that different from adding neo-Classical columns to the front of your McMansion, or adding neo-Victorian pastel gingerbreading to your bulletin board with a staple gun, as instructed in the how-to on page 346 of Martha Stewart Living. The difference is the scale; there’s something astonishing at the hubris involved in copying an entire town.

That scale is going to be dwarfed when we finally move out and colonize Mars. What structures will inform our idea of Mars? Bucky domes, or perhaps the terraces of Marvin Martian? Streamlined biospheres whose sunken dens permit permutations of Perky Pat? Or will the planetary Red-Green-Blue terraforming be our copying standard going forward…?

[Instant copied martians]

But back to the present, by which of course I mean our idea of it: any discussion of architecting ideas cannot leave out software. We inhabit and maintain multiple online copies — Second Life, avatars, Twitter streams — but what part of “real life” are we copying? And how well?

[Esciff, by kristofoletti, via LRJP!]

Not that we disapprove! Here at HILOBROW we love the copy. But when we model our ideas of the real back to ourselves, we might not want to copy too slavishly. We might want to add in a little wiggle room, a little aberration.

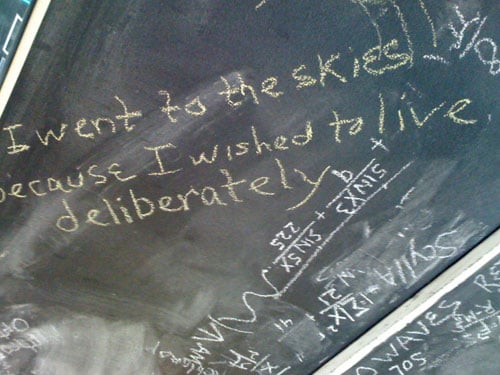

Because there can be more things on heaven and earth — once we dream them in our philosophies.

[Detail, The Shining, from All Utopias Fell by Michael Oatman, 2010, installation at MassMOCA]